Jul 09, 2025·8 min

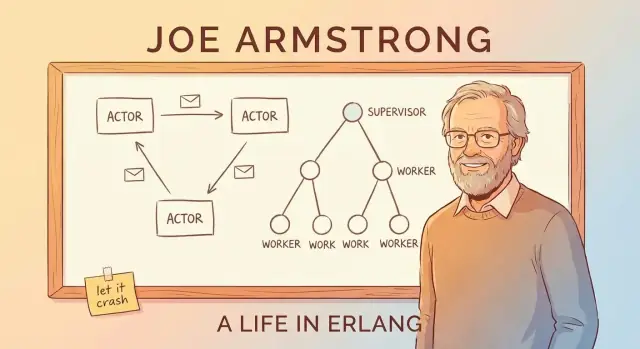

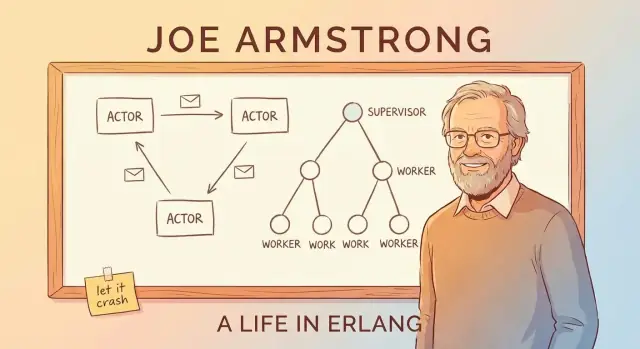

Joe Armstrong and Erlang: Let It Crash for Reliable Platforms

Explore how Joe Armstrong shaped Erlang’s concurrency, supervision, and “let it crash” mindset—ideas still used to build dependable real-time services.

Explore how Joe Armstrong shaped Erlang’s concurrency, supervision, and “let it crash” mindset—ideas still used to build dependable real-time services.

Joe Armstrong didn’t just help create Erlang—he became its clearest, most persuasive explainer. Through talks, papers, and a pragmatic point of view, he popularized a simple idea: if you want software that stays up, you design for failure instead of pretending you can avoid it.

This post is a guided tour of the Erlang mindset and why it still matters when you’re building reliable real-time platforms—things like chat systems, call routing, live notifications, multiplayer coordination, and infrastructure that needs to respond quickly and consistently even while parts of it misbehave.

Real-time doesn’t always mean “microseconds” or “hard deadlines.” In many products it means:

Erlang was built for telecom systems where these expectations are non-negotiable—and that pressure shaped its most influential ideas.

Rather than diving into syntax, we’ll focus on the concepts that made Erlang famous and keep reappearing in modern systems design:

Along the way, we’ll connect these ideas to the actor model and message passing, explain supervision trees and OTP in approachable terms, and show why the BEAM VM makes the whole approach practical.

Even if you’re not using Erlang (and never will), the point still holds: Armstrong’s framing gives you a powerful checklist for building systems that stay responsive and available when reality gets messy.

Telecom switches and call-routing platforms don’t get to “go down for maintenance” the way many websites can. They’re expected to keep handling calls, billing events, and signaling traffic around the clock—often with strict requirements for availability and predictable response times.

Erlang started inside Ericsson in the late 1980s as an attempt to meet those realities with software, not just specialized hardware. Joe Armstrong and his colleagues weren’t chasing elegance for its own sake; they were trying to build systems that operators could trust under constant load, partial failures, and messy real-world conditions.

A key shift in thinking is that reliability isn’t the same as “never failing.” In large, long-running systems, something will fail: a process will hit unexpected input, a node will reboot, a network link will flap, or a dependency will stall.

So the goal becomes:

This is the mindset that later makes ideas like supervision trees and “let it crash” feel reasonable: you design for failure as a normal event, not an exceptional catastrophe.

It’s tempting to tell the story as a single visionary’s breakthrough. The more useful view is simpler: telecom constraints forced a different set of tradeoffs. Erlang prioritized concurrency, isolation, and recovery because those were the practical tools needed to keep services running while the world kept changing around them.

That problem-first framing is also why Erlang’s lessons still translate well today—anywhere uptime and fast recovery matter more than perfect prevention.

A core idea in Erlang is that “doing many things at once” isn’t a special feature you bolt on later—it’s the normal way you structure a system.

In Erlang, work is split into lots of tiny “processes.” Think of them as small workers, each responsible for one job: handling a phone call, tracking a chat session, monitoring a device, retrying a payment, or watching a queue.

They’re lightweight, meaning you can have huge numbers of them without needing huge hardware. Instead of one heavyweight worker trying to juggle everything, you get a crowd of focused workers that can start quickly, stop quickly, and be replaced quickly.

Many systems are designed like a single big program with many parts tightly connected. When that kind of system hits a serious bug, a memory issue, or a blocking operation, the failure can ripple outward—like tripping one breaker and blacking out the whole building.

Erlang pushes the opposite: isolate responsibilities. If one small worker misbehaves, you can drop and replace that worker without taking down unrelated work.

How do these workers coordinate? They don’t poke around in each other’s internal state. They send messages—more like passing notes than sharing a messy whiteboard.

One worker can say, “Here’s a new request,” “This user disconnected,” or “Try again in 5 seconds.” The receiving worker reads the note and decides what to do.

The key benefit is containment: because workers are isolated and communicate by messages, failures are less likely to spread across the entire system.

A simple way to understand Erlang’s “actor model” is to picture a system made of many small, independent workers.

An actor is a self-contained unit with its own private state and a mailbox. It does three basic things:

That’s it. No hidden shared variables, no “reach into another worker’s memory.” If one actor needs something from another, it asks by sending a message.

When multiple threads share the same data, you can get race conditions: two things change the same value at nearly the same time, and the result depends on timing. That’s where bugs become intermittent and hard to reproduce.

With message passing, each actor owns its data. Other actors can’t mutate it directly. This doesn’t eliminate every bug, but it dramatically reduces issues caused by simultaneous access to the same piece of state.

Messages don’t arrive “for free.” If an actor receives messages faster than it can process them, its mailbox (queue) grows. That’s back-pressure: the system is telling you, indirectly, “this part is overloaded.”

In practice, you monitor mailbox sizes and build limits: shedding load, batching, sampling, or pushing work to more actors instead of letting queues grow forever.

Imagine a chat app. Each user could have an actor responsible for delivering notifications. When a user goes offline, messages keep arriving—so the mailbox grows. A well-designed system might cap the queue, drop non-critical notifications, or switch to digest mode, rather than letting one slow user degrade the whole service.

“Let it crash” isn’t a slogan for sloppy engineering. It’s a reliability strategy: when a component gets into a bad or unexpected state, it should stop quickly and loudly instead of limping along.

Rather than writing code that tries to handle every possible edge case inside one process, Erlang encourages keeping each worker small and focused. If that worker hits something it truly can’t handle (corrupt state, violated assumptions, unexpected input), it exits. Another part of the system is responsible for bringing it back.

This shifts the main question from “How do we prevent failure?” to “How do we recover cleanly when failure happens?”

Defensive programming everywhere can turn simple flows into a maze of conditionals, retries, and partial states. “Let it crash” trades some of that in-process complexity for:

The big idea is that recovery should be predictable and repeatable, not improvised inside every function.

It fits best when failures are recoverable and isolated: a temporary network issue, a bad request, a stuck worker, a third-party timeout.

It’s a poor fit when a crash could cause irreversible harm, such as:

Crashing only helps if coming back is quick and safe. In practice, that means restarting workers into a known-good state—often by reloading configuration, rebuilding in-memory caches from durable storage, and resuming work without pretending the broken state never existed.

Erlang’s “let it crash” idea only works because crashes aren’t left to chance. The key pattern is the supervision tree: a hierarchy where supervisors act like managers and workers do the actual job (handling a call, tracking a session, consuming a queue, etc.). When a worker misbehaves, the manager notices and restarts it.

A supervisor doesn’t try to “fix” a broken worker in place. Instead, it applies a simple, consistent rule: if the worker dies, start a fresh one. That makes the recovery path predictable and reduces the need for ad-hoc error handling sprinkled throughout the code.

Just as important, supervisors can also decide when not to restart—if something is crashing too often, it may indicate a deeper issue, and repeatedly restarting can make things worse.

Supervision isn’t one-size-fits-all. Common strategies include:

Good supervision design starts with a dependency map: which components rely on which others, and what “fresh start” really means for them.

If a session handler depends on a cache process, restarting only the handler might leave it connected to a bad state. Grouping them under the right supervisor (or restarting them together) turns messy failure modes into consistent, repeatable recovery behavior.

If Erlang is the language, OTP (Open Telecom Platform) is the kit of parts that turns “let it crash” into something you can run in production for years.

OTP isn’t a single library—it’s a set of conventions and ready-made components (called behaviours) that solve the boring-but-critical parts of building services:

gen_server for a long-running worker that keeps state and handles requests one at a timesupervisor for automatically restarting failed workers according to clear rulesapplication for defining how a whole service starts, stops, and fits into a releaseThese aren’t “magic.” They’re templates with well-defined callbacks, so your code plugs into a known shape instead of inventing a new shape every project.

Teams often build ad-hoc background workers, homegrown monitoring hooks, and one-off restart logic. It works—until it doesn’t. OTP reduces that risk by pushing everyone toward the same vocabulary and lifecycle. When a new engineer joins, they don’t have to learn your custom framework first; they can rely on shared patterns that are widely understood in the Erlang ecosystem.

OTP nudges you to think in terms of process roles and responsibilities: what is a worker, what is a coordinator, what should restart what, and what should never restart automatically.

It also encourages good hygiene: clear naming, explicit startup order, predictable shutdown, and built-in monitoring signals. The result is software that’s designed to run continuously—services that can recover from faults, evolve over time, and keep doing their job without constant human babysitting.

Erlang’s big ideas—tiny processes, message passing, and “let it crash”—would be much harder to use in production without the BEAM virtual machine (VM). BEAM is the runtime that makes these patterns feel natural, not fragile.

BEAM is built to run huge numbers of lightweight processes. Instead of relying on a handful of OS threads and hoping the application behaves, BEAM schedules Erlang processes itself.

The practical benefit is responsiveness under load: work is sliced into small chunks and rotated through fairly, so no single busy worker is meant to dominate the system for long. That fits perfectly with a service made of many independent tasks—each doing a bit of work, then yielding.

Each Erlang process has its own heap and its own garbage collection. That’s a key detail: cleaning up memory in one process doesn’t require pausing the whole program.

Just as important, processes are isolated. If one crashes, it doesn’t corrupt the memory of others, and the VM stays alive. This isolation is the foundation that makes supervision trees realistic: failure is contained, then handled by restarting the failed part rather than tearing everything down.

BEAM also supports distribution in straightforward terms: you can run multiple Erlang nodes (separate VM instances) and let them communicate by sending messages. If you’ve understood “processes talk by messaging,” distribution is an extension of the same idea—some processes just happen to live on another node.

BEAM isn’t about raw speed promises. It’s about making concurrency, fault containment, and recovery the default, so the reliability story is practical rather than theoretical.

One of Erlang’s most talked-about tricks is hot code swapping: updating parts of a running system with minimal downtime (where the runtime and tooling support it). The practical promise isn’t “never restart again,” but “ship fixes without turning a brief bug into a long outage.”

In Erlang/OTP, the runtime can keep two versions of a module loaded at once. Existing processes may finish work using the old version while new calls can start using the new one. That gives you room to patch a bug, roll out a feature, or adjust behavior without kicking everyone off the system.

Done well, this supports reliability goals directly: fewer full restarts, shorter maintenance windows, and quicker recovery when something slips into production.

Not every change is safe to swap live. Some examples of changes that need extra care (or a restart) include:

Erlang provides mechanisms for controlled transitions, but you still have to design the upgrade path.

Hot upgrades work best when upgrades and rollbacks are treated as routine operations, not rare emergencies. That means planning versioning, compatibility, and a clear “undo” path from the start. In practice, teams pair live-upgrade techniques with staged rollouts, health checks, and supervision-based recovery.

Even if you never use Erlang, the lesson transfers: design systems so changing them safely is a first-class requirement, not an afterthought.

Real-time platforms are less about perfect timing and more about staying responsive while things constantly go wrong: networks wobble, dependencies slow down, and user traffic spikes. Erlang’s design—championed by Joe Armstrong—fits this reality because it assumes failure and treats concurrency as normal, not exceptional.

You see Erlang-style thinking shine anywhere you have lots of independent activities happening at once:

Most products don’t need hard guarantees like “every action completes within 10 ms.” They need soft real-time: consistently low latency for typical requests, quick recovery when parts fail, and high availability so users rarely notice incidents.

Real systems hit issues like:

Erlang’s model encourages isolating each activity (a user session, a device, a payment attempt) so a failure doesn’t spread. Instead of building one giant “try to handle everything” component, teams can reason in smaller units: each worker does one job, talks via messages, and if it breaks, it’s restarted cleanly.

That shift—from “prevent every failure” to “contain and recover from failures quickly”—is often what makes real-time platforms feel stable under pressure.

Erlang’s reputation can sound like a promise: systems that never go down because they just restart. The reality is more practical—and more useful. “Let it crash” is a tool for building dependable services, not a license to ignore hard problems.

A common mistake is treating supervision as a way to hide deep bugs. If a process crashes immediately after starting, a supervisor may keep restarting it until you end up with a crash loop—burning CPU, spamming logs, and potentially causing a bigger outage than the original bug.

Good systems add backoff, restart intensity limits, and clear “give up and escalate” behavior. Restarts should restore healthy operation, not mask a broken invariant.

Restarting a process is often easy; recovering correct state is not. If state lives only in memory, you must decide what “correct” means after a crash:

Fault tolerance doesn’t replace careful data design. It forces you to be explicit about it.

Crashes are only helpful if you can see them early and understand them. That means investing in logging, metrics, and tracing—not just “it restarted, so we’re fine.” You want to notice rising restart rates, growing queues, and slow dependencies before users feel it.

Even with the BEAM’s strengths, systems can fail in very ordinary ways:

Erlang’s model helps you contain and recover from failures—but it can’t remove them.

Erlang’s biggest gift isn’t syntax—it’s a set of habits for building services that keep running when parts inevitably fail. You can apply those habits in almost any stack.

Start by making failure boundaries explicit. Break your system into components that can fail independently, and make sure each one has a clear contract (inputs, outputs, and what “bad” looks like).

Then automate recovery instead of trying to prevent every error:

One practical way to make these habits “real” is to bake them into the tooling and lifecycle, not just the code. For example, when teams use Koder.ai to vibe-code web, backend, or mobile apps via chat, the workflow naturally encourages explicit planning (Planning Mode), repeatable deployments, and safe iteration with snapshots and rollback—concepts that align with the same operational mindset Erlang popularized: assume change and failure will happen, and make recovery boring.

You can approximate “supervision” patterns with tools you may already use:

Before you copy patterns, decide what you actually need:

If you want practical next steps, see more guides in /blog, or browse implementation details in /docs (and plans in /pricing if you’re evaluating tooling).

Erlang popularized a practical reliability mindset: assume parts will fail and design what happens next.

Instead of trying to prevent every crash, it emphasizes fault isolation, fast detection, and automatic recovery, which maps well to real-time platforms like chat, call routing, notifications, and coordination services.

In this context, “real-time” usually means soft real-time:

It’s less about microsecond deadlines and more about avoiding stalls, spirals, and cascading outages.

Concurrency-by-default means structuring the system as many small, isolated workers rather than a few large, tightly coupled components.

Each worker handles a narrow responsibility (a session, device, call, retry loop), which makes scaling and failure containment easier.

Lightweight processes are small independent workers you can create in large numbers.

Practically, they help because:

Message passing is coordination by sending messages rather than sharing mutable state.

This helps reduce whole classes of concurrency bugs (like race conditions) because each worker owns its internal state; others can only request changes indirectly via messages.

Back-pressure happens when a worker receives messages faster than it can handle them, so its mailbox grows.

Practical ways to deal with it include:

“Let it crash” means: if a worker reaches an invalid or unexpected state, it should fail fast rather than limp along.

Recovery is handled structurally (via supervision), which can produce simpler code paths and more predictable recovery—provided restarts are safe and fast.

A supervision tree is a hierarchy where supervisors monitor workers and restart them according to defined rules.

Instead of sprinkling ad-hoc recovery everywhere, you centralize it:

OTP is the set of standard patterns (behaviours) and conventions that make Erlang systems operable long-term.

Common building blocks include:

gen_server for stateful workerssupervisor for restart policiesapplication for clean start/stop and releasesThe advantage is shared, well-understood lifecycles instead of one-off frameworks.

You can apply the same principles in other stacks by making failure and recovery first-class:

For more, the post points to related guides in /blog and implementation details in /docs.