Oct 31, 2025·8 min

Joe Beda’s Early Kubernetes Decisions That Shaped Platforms

A clear look at Joe Beda’s early Kubernetes choices—declarative APIs, control loops, Pods, Services, and labels—and how they shaped modern app platforms.

A clear look at Joe Beda’s early Kubernetes choices—declarative APIs, control loops, Pods, Services, and labels—and how they shaped modern app platforms.

Joe Beda was one of the key people behind Kubernetes’ earliest design—alongside other founders who carried lessons from Google’s internal systems into an open platform. His influence wasn’t about chasing trendy features; it was about choosing simple primitives that could survive real production chaos and still be understandable by everyday teams.

Those early decisions are why Kubernetes became more than “a container tool.” It turned into a reusable kernel for modern application platforms.

“Container orchestration” is the set of rules and automation that keeps your app running when machines fail, traffic spikes, or you deploy a new version. Instead of a human babysitting servers, the system schedules containers onto computers, restarts them when they crash, spreads them out for resilience, and wires up networking so users can reach them.

Before Kubernetes became common, teams often stitched together scripts and custom tools to answer basic questions:

Those DIY systems worked—until they didn’t. Every new app or team added more one-off logic, and operational consistency was hard to achieve.

This article walks through early Kubernetes design choices (the “shape” of Kubernetes) and why they still influence modern platforms: the declarative model, controllers, Pods, labels, Services, a strong API, consistent cluster state, pluggable scheduling, and extensibility. Even if you’re not running Kubernetes directly, you’re likely using a platform built on these ideas—or struggling with the same problems.

Before Kubernetes, “running containers” usually meant running a few containers. Teams stitched together bash scripts, cron jobs, golden images, and a handful of ad-hoc tools to get things deployed. When something broke, the fix often lived in someone’s head—or in a README nobody trusted. Operations was a stream of one-off interventions: restarting processes, re-pointing load balancers, cleaning up disk, and guessing which machine was safe to touch.

Containers made packaging easier, but they didn’t remove the messy parts of production. At scale, the system fails in more ways and more often: nodes disappear, networks partition, images roll out inconsistently, and workloads drift from what you think is running. A “simple” deploy can turn into a cascade—some instances updated, some not, some stuck, some healthy but unreachable.

The real issue wasn’t starting containers. It was keeping the right containers running, in the right shape, despite constant churn.

Teams were also juggling different environments: on‑prem hardware, VMs, early cloud providers, and various network and storage setups. Each platform had its own vocabulary and failure patterns. Without a shared model, every migration meant rewriting operational tooling and retraining people.

Kubernetes set out to offer a single, consistent way to describe applications and their operational needs, regardless of where the machines lived.

Developers wanted self-service: deploy without tickets, scale without begging for capacity, and roll back without drama. Ops teams wanted predictability: standardized health checks, repeatable deployments, and a clear source of truth for what should be running.

Kubernetes wasn’t trying to be a fancy scheduler. It was aiming to be the foundation for a dependable application platform—one that turns messy reality into a system you can reason about.

One of the most influential early choices was making Kubernetes declarative: you describe what you want, and the system works to make reality match that description.

A thermostat is a useful everyday example. You don’t manually turn the heater on and off every few minutes. You set a desired temperature—say 21°C—and the thermostat keeps checking the room and adjusting the heater to stay close to that target.

Kubernetes works the same way. Instead of telling the cluster, step by step, “start this container on that machine, then restart it if it fails,” you declare the outcome: “I want 3 copies of this app running.” Kubernetes continuously checks what’s actually running and corrects drift.

Declarative configuration reduces the hidden “ops checklist” that often lives in someone’s head or in a half-updated runbook. You apply the config, and Kubernetes handles the mechanics—placement, restarts, and reconciling changes.

It also makes change review easier. A change is visible as a diff in configuration, not a series of ad-hoc commands.

Because the desired state is written down, you can reuse the same approach in dev, staging, and production. The environment may differ, but the intent stays consistent, which makes deployments more predictable and easier to audit.

Declarative systems have a learning curve: you need to think in “what should be true” rather than “what do I do next.” They also depend heavily on good defaults and clear conventions—without them, teams can produce configs that technically work but are hard to understand and maintain.

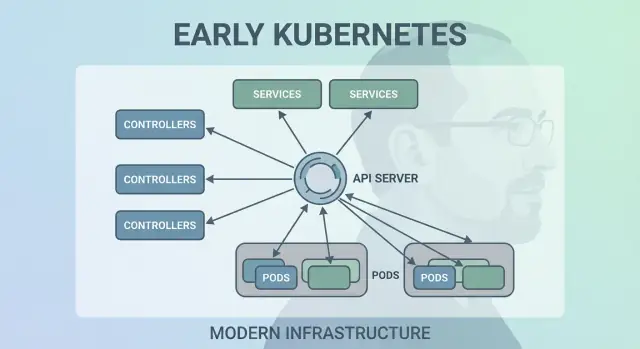

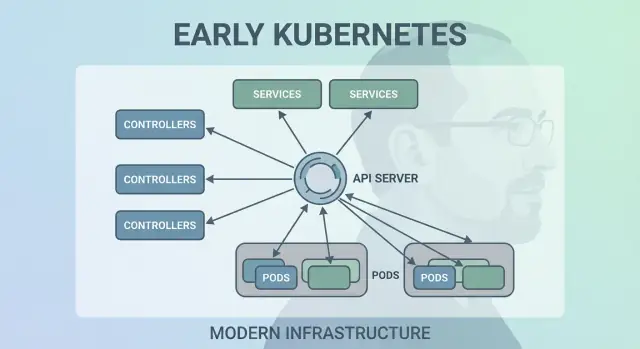

Kubernetes didn’t succeed because it could run containers once—it succeeded because it could keep them running correctly over time. The big design move was to make “control loops” (controllers) the core engine of the system.

A controller is a simple loop:

It’s less like a one-time task and more like autopilot. You don’t “babysit” workloads; you declare what you want, and controllers keep steering the cluster back to that outcome.

This pattern is why Kubernetes is resilient when real-world things go wrong:

Instead of treating failures as special cases, controllers treat them as routine “state mismatch” and fix them the same way every time.

Traditional automation scripts often assume a stable environment: run step A, then B, then C. In distributed systems, those assumptions break constantly. Controllers scale better because they’re idempotent (safe to run repeatedly) and eventually consistent (they keep trying until the goal is reached).

If you’ve used a Deployment, you’ve relied on control loops. Under the hood, Kubernetes uses a ReplicaSet controller to ensure the requested number of pods exist—and a Deployment controller to manage rolling updates and rollbacks predictably.

Kubernetes could have scheduled “just containers,” but Joe Beda’s team introduced Pods to represent the smallest deployable unit the cluster places on a machine. The key idea: many real applications aren’t a single process. They’re a small group of tightly coupled processes that must live together.

A Pod is a wrapper around one or more containers that share the same fate: they start together, run on the same node, and scale together. This makes patterns like sidecars natural—think of a log shipper, proxy, config reloader, or security agent that should always accompany the main app.

Instead of teaching every app to integrate those helpers, Kubernetes lets you package them as separate containers that still behave like one unit.

Pods made two important assumptions practical:

localhost, which is simple and fast.These choices reduced the need for custom glue code, while keeping containers isolated at the process level.

New users often expect “one container = one app,” then get tripped up by Pod-level concepts: restarts, IPs, and scaling. Many platforms smooth this over by providing opinionated templates (for example, “web service,” “worker,” or “job”) that generate Pods behind the scenes—so teams get the benefits of sidecars and shared resources without having to think about Pod mechanics every day.

A quietly powerful early choice in Kubernetes was to treat labels as first-class metadata and selectors as the primary way to “find” things. Instead of hard-wiring relationships (like “these exact three machines run my app”), Kubernetes encourages you to describe groups by shared attributes.

A label is a simple key/value pair you attach to resources—Pods, Deployments, Nodes, Namespaces, and more. They act like consistent, queryable “tags”:

app=checkoutenv=prodtier=frontendBecause labels are lightweight and user-defined, you can model your organization’s reality: teams, cost centers, compliance zones, release channels, or whatever matters to how you operate.

Selectors are queries over labels (for example, “all Pods where app=checkout and env=prod”). This beats fixed host lists because the system can adapt as Pods are rescheduled, scaled up/down, or replaced during rollouts. Your configuration stays stable even when the underlying instances are constantly changing.

This design scales operationally: you don’t manage thousands of instance identities—you manage a few meaningful label sets. That’s the essence of loose coupling: components connect to groups that can change membership safely.

Once labels exist, they become a shared vocabulary across the platform. They’re used for traffic routing (Services), policy boundaries (NetworkPolicy), observability filters (metrics/logs), and even cost tracking and chargeback. One simple idea—tag things consistently—unlocks a whole ecosystem of automation.

Kubernetes needed a way to make networking feel predictable even though containers are anything but. Pods get replaced, rescheduled, and scaled up and down—so their IPs and even the specific machines they run on will change. The core idea of a Service is simple: provide a stable “front door” to a shifting set of Pods.

A Service gives you a consistent virtual IP and DNS name (like payments). Behind that name, Kubernetes continuously tracks which Pods match the Service’s selector and routes traffic accordingly. If a Pod dies and a new one appears, the Service still points to the right place without you touching application settings.

This approach removed a lot of manual wiring. Instead of baking IPs into config files, apps can depend on names. You deploy the app, deploy the Service, and other components can find it via DNS—no custom registry required, no hard-coded endpoints.

Services also introduced default load-balancing behavior across healthy endpoints. That meant teams didn’t have to build (or rebuild) their own load balancers for every internal microservice. Spreading traffic reduces the blast radius of a single Pod failure and makes rolling updates less risky.

A Service is great for L4 (TCP/UDP) traffic, but it doesn’t model HTTP routing rules, TLS termination, or edge policies. That’s where Ingress and, increasingly, the Gateway API fit: they build on Services to handle hostnames, paths, and external entry points more cleanly.

One of the most quietly radical early choices was treating Kubernetes as an API you build against—not a monolithic tool you “use.” That API-first stance made Kubernetes feel less like a product you click through and more like a platform you can extend, script, and govern.

When the API is the surface area, platform teams can standardize how applications are described and managed, regardless of which UI, pipeline, or internal portal sits on top. “Deploying an app” becomes “submitting and updating API objects” (like Deployments, Services, and ConfigMaps), which is a much cleaner contract between app teams and the platform.

Because everything goes through the same API, new tooling doesn’t need privileged backdoors. Dashboards, GitOps controllers, policy engines, and CI/CD systems can all operate as normal API clients with well-scoped permissions.

That symmetry matters: the same rules, auth, auditing, and admission controls apply whether the request came from a person, a script, or an internal platform UI.

API versioning made it possible to evolve Kubernetes without breaking every cluster or every tool overnight. Deprecations can be staged; compatibility can be tested; upgrades can be planned. For organizations running clusters for years, this is the difference between “we can upgrade” and “we’re stuck.”

kubectl is not Kubernetes—it’s a client. That mental model pushes teams to think in terms of API workflows: you can swap kubectl for automation, a web UI, or a custom portal, and the system stays consistent because the contract is the API itself.

Kubernetes needed a single “source of truth” for what the cluster should look like right now: which Pods exist, which nodes are healthy, what Services point to, and which objects are being updated. That’s what etcd provides.

etcd is the database for the control plane. When you create a Deployment, scale a ReplicaSet, or update a Service, the desired configuration is written to etcd. Controllers and other control-plane components then watch that stored state and work to make reality match it.

A Kubernetes cluster is full of moving parts: schedulers, controllers, kubelets, autoscalers, and admission checks can all react simultaneously. If they’re reading different versions of “the truth,” you get races—like two components making conflicting decisions about the same Pod.

etcd’s strong consistency ensures that when the control plane says “this is the current state,” everyone is aligned. That alignment is what makes control loops predictable instead of chaotic.

Because etcd holds the cluster’s configuration and history of changes, it’s also what you protect during:

Treat control-plane state like critical data. Take regular etcd snapshots, test restores, and store backups off-cluster. If you run managed Kubernetes, learn what your provider backs up—and what you still need to back up yourself (for example, persistent volumes and app-level data).

Kubernetes didn’t treat “where a workload runs” as an afterthought. Early on, the scheduler was a distinct component with a clear job: match Pods to nodes that can actually run them, using the cluster’s current state and the Pod’s requirements.

At a high level, scheduling is a two-step decision:

This structure made it possible to evolve Kubernetes scheduling without rewriting everything.

A key design choice was keeping responsibilities clean:

Because these concerns are separated, improvements in one area (say, a new CNI networking plugin) don’t force a new scheduling model.

Resource awareness started with requests and limits, giving the scheduler meaningful signals instead of guesswork. From there, Kubernetes added richer controls—node affinity/anti-affinity, pod affinity, priorities and preemption, taints and tolerations, and topology-aware spreading—built on the same foundation.

This approach enables today’s shared clusters: teams can isolate critical services with priorities and taints, while everyone benefits from higher utilization. With better bin-packing and topology controls, platforms can place workloads more cost-effectively without sacrificing reliability.

Kubernetes could have shipped with a full, opinionated platform experience—buildpacks, app routing rules, background jobs, config conventions, and more. Instead, Joe Beda and the early team kept the core focused on a smaller promise: run and heal workloads reliably, expose them, and provide a consistent API to automate against.

A “complete PaaS” would have forced one workflow and one set of trade-offs on everyone. Kubernetes targeted a broader foundation that could support many platform styles—Heroku-like developer simplicity, enterprise governance, batch + ML pipelines, or barebones infrastructure control—without locking in a single product philosophy.

Kubernetes’ extensibility mechanisms created a controlled way to grow capabilities:

Certificate or Database) that look and feel native.This means internal platform teams and vendors can ship features as add-ons, while still using Kubernetes primitives like RBAC, namespaces, and audit logs.

For vendors, it enables differentiated products without forking Kubernetes. For internal teams, it enables a “platform on Kubernetes” tailored to organizational needs.

The trade-off is ecosystem sprawl: too many CRDs, overlapping tools, and inconsistent conventions. Governance—standards, ownership, versioning, and deprecation rules—becomes part of the platform work.

Kubernetes’ early choices didn’t just create a container scheduler—they created a reusable platform kernel. That’s why so many modern internal developer platforms (IDPs) are, at their core, “Kubernetes plus opinionated workflows.” The declarative model, controllers, and a consistent API made it possible to build higher-level products—without reinventing deployment, reconciliation, and service discovery each time.

Because the API is the product surface, vendors and platform teams can standardize on one control plane and build different experiences on top: GitOps, multi-cluster management, policy, service catalogs, and deployment automation. This is a big reason Kubernetes became the common denominator for cloud native platforms: integrations target the API, not a specific UI.

Even with clean abstractions, the toughest work is still operational:

Ask questions that reveal operational maturity:

A good platform reduces cognitive load without hiding the underlying control plane or making escape hatches painful.

One practical lens: does the platform help teams move from “idea → running service” without forcing everyone to become Kubernetes experts on day one? Tools in the “vibe-coding” category—like Koder.ai—lean into this by letting teams generate real applications from chat (web in React, backends in Go with PostgreSQL, mobile in Flutter) and then iterate quickly with features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback. Whether you adopt something like that or build your own portal, the goal is the same: preserve Kubernetes’ strong primitives while reducing the workflow overhead around them.

Kubernetes can feel complicated, but most of its “weirdness” is intentional: it’s a set of small primitives designed to compose into many kinds of platforms.

First: “Kubernetes is just Docker orchestration.” Kubernetes isn’t primarily about starting containers. It’s about continuously reconciling desired state (what you want running) with actual state (what’s really happening), across failures, rollouts, and changing demand.

Second: “If we use Kubernetes, everything becomes microservices.” Kubernetes supports microservices, but it also supports monoliths, batch jobs, and internal platforms. The units (Pods, Services, labels, controllers, and the API) are neutral; your architecture choices aren’t dictated by the tool.

The hard parts usually aren’t YAML or Pods—they’re networking, security, and multi-team usage: identity and access, secrets management, policies, ingress, observability, supply-chain controls, and creating guardrails so teams can ship safely without stepping on each other.

When planning, think in terms of the original design bets:

Map your real requirements to Kubernetes primitives and platform layers:

Workloads → Pods/Deployments/Jobs

Connectivity → Services/Ingress

Operations → controllers, policies, and observability

If you’re evaluating or standardizing, write this mapping down and review it with stakeholders—then build your platform incrementally around the gaps, not around trends.

If you’re also trying to speed up the “build” side (not just the “run” side), consider how your delivery workflow turns intent into deployable services. For some teams that’s a curated set of templates; for others it’s an AI-assisted workflow like Koder.ai that can produce an initial working service quickly and then export source code for deeper customization—while your platform still benefits from Kubernetes’ core design decisions underneath.

Container orchestration is the automation that keeps apps running as machines fail, traffic changes, and deployments happen. In practice it handles:

Kubernetes popularized a consistent model for doing this across different infrastructure environments.

The main problem wasn’t starting containers—it was keeping the right containers running in the right shape despite constant churn. At scale you get routine failures and drift:

Kubernetes aimed to make operations repeatable and predictable by giving a standard control plane and vocabulary.

In a declarative system you describe the outcome you want (for example, “run 3 replicas”), and the system continuously works to make reality match.

Practical workflow:

kubectl apply or GitOps)This reduces “hidden runbooks” and makes changes reviewable as diffs instead of ad-hoc commands.

Controllers are control loops that repeatedly:

That design makes common failures routine instead of special-case logic. For example, if a Pod crashes or a node disappears, the relevant controller simply notices “we have fewer replicas than desired” and creates replacements.

Kubernetes schedules Pods (not individual containers) because many real workloads need tightly coupled helper processes.

Pods enable patterns like:

localhost)Rule of thumb: keep Pods small and cohesive—only group containers that must share lifecycle, network identity, or local data.

Labels are lightweight key/value tags (for example app=checkout, env=prod). Selectors query those labels to form dynamic groups.

This matters because instances are ephemeral: Pods come and go during reschedules and rollouts. With labels/selectors, relationships are stable (“all Pods with these labels”) even when members change.

Operational tip: standardize a small label taxonomy (app, team, env, tier) and enforce it with policy to avoid chaos later.

A Service provides a stable virtual IP and DNS name that routes to a changing set of Pods matching a selector.

Use a Service when:

For HTTP routing, TLS termination, and edge rules, you typically layer Ingress or Gateway API on top of Services.

Kubernetes treats the API as the primary product surface: everything is an API object (Deployments, Services, ConfigMaps, etc.). Tools—including kubectl, CI/CD, GitOps, dashboards—are just API clients.

Practical benefits:

If you’re building an internal platform, design workflows around API contracts, not around a specific UI tool.

etcd is the control plane’s database and the cluster’s source of truth for desired and current state. Controllers and other components watch etcd and reconcile based on that state.

Practical guidance:

In managed Kubernetes, learn what your provider backs up—and what still needs separate backup (for example, persistent volumes and application data).

Kubernetes stays small at the core and lets you add features via extensions:

This enables “platform on Kubernetes,” but it can lead to tool sprawl. To evaluate a Kubernetes-based platform, ask: