Dec 18, 2025·8 min

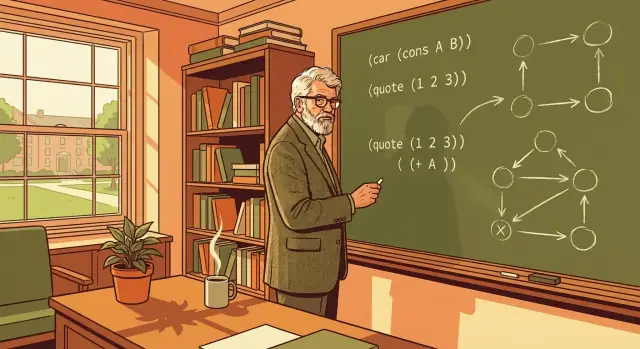

John McCarthy, Lisp, and the Roots of Symbolic AI Design

Explore how John McCarthy’s symbolic approach and Lisp design ideas—lists, recursion, and garbage collection—influenced AI and modern programming.

Explore how John McCarthy’s symbolic approach and Lisp design ideas—lists, recursion, and garbage collection—influenced AI and modern programming.

This isn’t a museum tour of “old AI.” It’s a practical history lesson for anyone who builds software—programmers, tech leads, and product builders—because John McCarthy’s ideas shaped how we think about what programming languages are for.

Lisp wasn’t just a new syntax. It was a bet that software could manipulate ideas (not only numbers) and that language design choices could accelerate research, product iteration, and entire tooling ecosystems.

A useful way to read McCarthy’s legacy is as a question that still matters today: how directly can we turn intent into an executable system—without drowning in boilerplate, friction, or accidental complexity? That question echoes from Lisp’s REPL all the way to modern “chat-to-app” workflows.

John McCarthy is remembered not just for helping launch AI as a research field, but for insisting on a specific kind of AI: systems that could manipulate ideas, not merely calculate answers. In the mid-1950s, he organized the Dartmouth Summer Research Project (where the term “artificial intelligence” was proposed) and went on to shape AI work at MIT and later Stanford. But his most lasting contribution may be the question he kept pushing: what if reasoning itself could be expressed as a program?

Most early computing successes were numeric: ballistics tables, engineering simulations, optimization, and statistics. These problems fit neatly into arithmetic.

McCarthy aimed at something different. Human reasoning often works with concepts like “if,” “because,” “belongs to,” “is a kind of,” and “all things that meet these conditions.” Those are not naturally represented as floating-point values.

McCarthy’s approach treated knowledge as symbols (names, relations, categories) and treated thinking as rule-based transformations over those symbols.

A high-level way to picture it: numeric approaches answer “how much?” while symbolic approaches try to answer “what is it?” and “what follows from what we know?”

Once you believe reasoning can be made programmable, you need a language that can comfortably represent expressions like rules, logical statements, and nested relationships—and then process them.

Lisp was built to serve that goal. Instead of forcing ideas into rigid, pre-baked data structures, Lisp made it natural to represent code and knowledge in a similar shape. That choice wasn’t academic style—it was a practical bridge between describing a thought and executing a procedure, which is exactly the bridge McCarthy wanted AI to cross.

When McCarthy and early AI researchers said “symbolic,” they didn’t mean mysterious math. A symbol is simply a meaningful label: a name like customer, a word like hungry, or a tag like IF and THEN. Symbols matter because they let a program work with ideas (categories, relationships, rules) rather than only raw numbers.

A simple way to picture it: spreadsheets are great when your world is columns and arithmetic. Symbolic systems are great when your world is rules, categories, exceptions, and structure.

In many programs, the difference between 42 and "age" is not the data type—it’s what the value stands for. A symbol gives you something you can compare, store, and combine without losing meaning.

That makes it natural to represent things like “Paris is a city” or “if the battery is low, find a charger.”

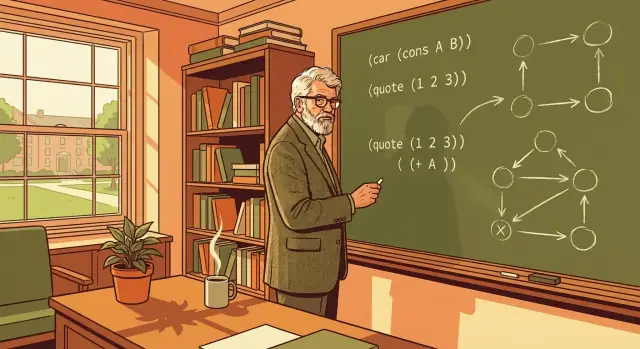

To do anything useful with symbols, you need structure. Lisp popularized a very plain structure: the list. A list is just an ordered group of items, and those items can themselves be lists. With that one idea, you can represent sentences, forms, and tree-shaped knowledge.

Here’s a tiny conceptual example (shown in a Lisp-like style):

(sentence (subject robot) (verb needs) (object power))

It reads almost like English: a sentence made of a subject, verb, and object. Because it’s structured, a program can pick out (subject robot) or replace (object power) with something else.

Once information is in symbolic structures, classic AI tasks become approachable:

IF a pattern matches, THEN conclude something new.The key shift is that the program isn’t just calculating; it’s manipulating meaningful pieces of knowledge in a form it can inspect and transform.

Lisp’s design decisions didn’t stay inside academia. They influenced how people built tools and how quickly they could explore ideas:

Those traits tend to produce ecosystems where experimentation is cheap, prototypes become products faster, and teams can adapt when requirements change.

Lisp started with a very practical design problem: how do you write programs that can work with symbols as naturally as they work with numbers?

McCarthy wasn’t trying to build a “better calculator.” He wanted a language where an expression like (is (parent Alice Bob)) could be stored, inspected, transformed, and reasoned about as easily as (+ 2 3).

The priority was to make symbolic information easy to represent and manipulate. That led to a focus on lists and tree-like structures, because they map well to things humans already use to express meaning: sentences, logical rules, nested categories, and relationships.

Another goal was to keep the core of the language small and consistent. When a language has fewer “special cases,” you spend less time memorizing rules and more time composing ideas. Lisp leaned into a tiny set of building blocks that could be combined into bigger abstractions.

A key insight was that programs and data can share the same kind of structure. Put simply: if your data is a nested list, your program can be a nested list too.

That means you can:

Lisp also popularized a mindset: languages don’t have to be one-size-fits-all. They can be designed around a problem domain—like reasoning, search, and knowledge representation—and still end up influencing general-purpose programming for decades.

S-expressions (short for symbolic expressions) are Lisp’s signature idea: a single, consistent way to represent code and data as nested lists.

At a glance, an S-expression is just parentheses around items—some items are atoms (like names and numbers), and some items are lists themselves. That “lists inside lists” rule is the whole point.

Because the structure is uniform, Lisp programs are built from the same building blocks all the way down. A function call, a configuration-like chunk of data, and a piece of program structure can all be expressed as a list.

That consistency pays off immediately:

Even if you never write Lisp, this is an important design lesson: when a system is built from one or two predictable forms, you spend less time fighting edge cases and more time building.

S-expressions encourage composition because small, readable pieces naturally combine into bigger ones. When your program is “just nested lists,” combining ideas often means nesting one expression inside another, or assembling lists from reusable parts.

This nudges you toward a modular style: you write tiny operations that do one thing, then stack them together to express a larger intent.

The obvious downside is unfamiliarity. To many newcomers, parentheses-heavy syntax looks strange.

But the upside is predictability: once you understand the nesting rules, you can reliably see the structure of a program—and tools can, too. That clarity is a big reason S-expressions had consequences far beyond Lisp itself.

Recursion is easiest to understand with an everyday metaphor: cleaning a messy room by making smaller “rooms” out of it. You don’t try to solve everything at once. You pick up one item, put it where it belongs, then repeat the same action on what remains. The steps are simple; the power comes from repeating them until there’s nothing left to do.

Lisp leans into this idea because so much of its data is naturally built from lists: a list has a “first thing” and “the rest.” That shape fits recursive thinking perfectly.

To process a list, you handle the first element, then apply the same logic to the rest of the list. When the list is empty, you stop—this is the clean “nothing left to do” moment that makes recursion feel well-defined rather than mysterious.

Imagine you want the total of a list of numbers.

That’s it. The definition reads like plain English, and the program structure mirrors the idea.

Symbolic AI often represents expressions as tree-like structures (an operator with sub-expressions). Recursion is a natural way to “walk” that tree: evaluate the left part the same way you evaluate the right part, and keep going until you reach a simple value.

These patterns helped shape later functional programming: small functions, clear base cases, and data transformations that are easy to reason about. Even outside Lisp, the habit of breaking work into “do one step, then repeat on the remainder” leads to cleaner programs and fewer hidden side effects.

Early programmers often had to manage memory by hand: allocating space, tracking who “owns” it, and remembering to free it at the right moment. That work doesn’t just slow development—it creates a special class of bugs that are hard to reproduce and easy to ship: leaks that silently degrade performance, and dangling pointers that crash a program long after the original mistake.

John McCarthy introduced garbage collection for Lisp as a way to let programmers focus on meaning rather than bookkeeping.

At a high level, garbage collection (GC) automatically finds pieces of memory that are no longer reachable from the running program—values that nothing can ever use again—and reclaims that space.

Instead of asking “did we free every object exactly once?”, GC shifts the question to “is this object still accessible?”. If the program can’t reach it, it’s considered garbage.

For symbolic AI work, Lisp programs frequently create lots of short-lived lists, trees, and intermediate results. Manual memory management would turn experimentation into a constant battle with resource cleanup.

GC changes the day-to-day experience:

The key idea is that a language feature can be a team multiplier: fewer hours spent debugging mysterious corruption means more time spent improving the actual logic.

McCarthy’s choice didn’t stay inside Lisp. Many later systems adopted GC (and variations of it) because the trade-off often pays for itself: Java, C#, Python, JavaScript runtimes, and Go all lean on garbage collection to make large-scale development safer and faster—even when performance is a priority.

In Lisp, an expression is a piece of code written in a consistent shape (often a list). Evaluation is simply the process of deciding what that expression means and what it produces.

For example, when you write something like “add these numbers” or “call this function with these inputs,” the evaluator follows a small set of rules to turn that expression into a result. Think of it as the language’s referee: it decides what to do next, in what order, and when to stop.

McCarthy’s key move wasn’t just inventing new syntax—it was keeping the “meaning engine” compact and regular. When the evaluator is built from a few clear rules, two good things happen:

That consistency is one reason Lisp became a playground for ideas in symbolic AI: researchers could try new representations and control structures quickly, without waiting for a compiler team to redesign the language.

Macros are Lisp’s way of letting you automate repetitive code shapes, not just repetitive values. Where a function helps you avoid repeating calculations, a macro helps you avoid repeating structures—common patterns like “do X, but also log it,” or “define a mini-language for rules.”

The practical effect is that Lisp can grow new conveniences from within. Many modern tools echo this idea—template systems, code generators, and metaprogramming features—because they support the same goal: faster experimentation and clearer intent.

If you’re curious how this mindset influenced everyday development workflows, see /blog/the-repl-and-fast-feedback-loops.

A big part of Lisp’s appeal wasn’t just the language—it was how you worked with it. Lisp popularized the REPL: Read–Eval–Print Loop. In everyday terms, it’s like having a conversation with the computer. You type an expression, the system runs it immediately, prints the result, and waits for your next input.

Instead of writing a whole program, compiling it, running it, and then hunting for what broke, you can try ideas one small step at a time. You can define a function, test it with a few inputs, tweak it, and test again—all in seconds.

That rhythm encourages experimentation, which mattered a lot for early AI work where you often didn’t know the right approach upfront.

Fast feedback turns “big bets” into “small checks.” For research, it makes it easier to explore hypotheses and inspect intermediate results.

For product prototyping, it reduces the cost of iteration: you can validate behavior with real data quickly, notice edge cases sooner, and refine features without waiting on long build cycles.

This is also why modern vibe-coding tools are compelling: they’re essentially an aggressive feedback-loop compression. For example, Koder.ai uses a chat interface (with an agent-based architecture under the hood) to turn product intent into working web, backend, or mobile code quickly—often making the “try → adjust → try again” loop feel closer to a REPL than a traditional pipeline.

The REPL idea shows up today in:

Different tools, same principle: shorten the distance between thinking and seeing.

Teams benefit most from REPL-like workflows when they’re exploring uncertain requirements, building data-heavy features, designing APIs, or debugging tricky logic. If the work involves rapid learning—about users, data, or edge cases—interactive feedback is not a luxury; it’s a multiplier.

Lisp didn’t “win” by becoming everyone’s daily syntax. It won by seeding ideas that quietly became normal across many ecosystems.

Concepts that Lisp treated as default—functions as values, heavy use of higher-order operations, and a preference for building programs by composing small parts—show up widely now. Even languages that look nothing like Lisp encourage map/filter-style transformations, immutable data habits, and recursion-like thinking (often expressed with iterators or folds).

The key shift is mental: treat data transformations as pipelines, and treat behavior as something you can pass around.

Lisp made programs easy to represent as data. That mindset shows up today in how we build and manipulate ASTs (abstract syntax trees) for compilers, formatters, linters, and code generators. When you’ve worked with an AST, you’re doing a close cousin of “code as data,” even if the structures are JSON objects, typed nodes, or bytecode graphs.

The same symbolic approach powers practical automation: configuration formats, templating systems, and build pipelines all rely on structured representations that tools can inspect, transform, and validate.

Modern Lisp-family languages (in the broad sense: contemporary Lisps and Lisp-inspired tools) keep influencing how teams design internal DSLs—small, focused mini-languages for tests, deployment, data wrangling, or UI.

Outside Lisp, macro systems, metaprogramming libraries, and code generation frameworks aim for the same outcome: extend the language to fit the problem.

A pragmatic takeaway: syntax preferences change, but the durable ideas—symbolic structure, composable functions, and extensibility—keep paying rent across decades and codebases.

Lisp has a reputation that swings between “brilliant” and “unreadable,” often based on secondhand impressions rather than day-to-day experience. The truth is more ordinary: Lisp makes some choices that are powerful in the right setting and inconvenient in others.

For newcomers, Lisp’s uniform syntax can feel like looking at the “inside” of a program rather than the polished surface. That discomfort is real, especially if you’re used to languages where syntax visually separates different constructs.

Historically, though, Lisp’s structure is also the point: code and data share the same shape, which makes programs easier to transform, generate, and analyze. With good editor support (indentation, structural navigation), Lisp code is often read more by shape than by counting parentheses.

A common stereotype is that Lisp is inherently slow. Historically, some implementations did struggle compared to low-level languages, and dynamic features can add overhead.

But it’s not accurate to treat “Lisp” as a single performance profile. Many Lisp systems have long supported compilation, type declarations, and serious optimization. The more useful framing is: how much control do you need over memory layout, predictable latency, or raw throughput—and does your Lisp implementation target those needs?

Another fair criticism is ecosystem fit. Depending on the Lisp dialect and domain, libraries, tooling, and hiring pools may be smaller than mainstream stacks. That can matter more than language elegance if you’re shipping quickly with a broad team.

Rather than judging Lisp by its stereotypes, evaluate its underlying ideas independently: uniform structure, interactive development, and macros as a tool for building domain-specific abstractions. Even if you never ship a Lisp system, those concepts can sharpen how you think about language design—and how you write code in any language.

McCarthy didn’t just leave us a historic language—he left a set of habits that still make software easier to change, explain, and extend.

Prefer simple cores over clever surfaces. A small set of orthogonal building blocks is easier to learn and harder to break.

Keep data shapes uniform. When many things share the same representation (like lists/trees), tooling becomes simpler: printers, debuggers, serializers, and transformers can be reused.

Treat programs as data (and data as programs) when it helps. If you can inspect and transform structures, you can build safer refactors, migrations, and code generators.

Automate the boring work. Garbage collection is the classic example, but the broader point is: invest in automation that prevents whole classes of mistakes.

Optimize for feedback loops. Interactive evaluation (REPL-style) encourages small experiments, quick verification, and better intuition about behavior.

Make extension a first-class design goal. Lisp macros are one answer; in other ecosystems this might be plugins, templates, DSLs, or compile-time transforms.

Before choosing a library or architecture, take a real feature—say “discount rules” or “support ticket routing”—and draw it as a tree. Then rewrite that tree as nested lists (or JSON). Ask: what are the nodes, what are the leaves, and what transformations do you need?

Even without Lisp, you can adopt the mindset: build AST-like representations, use code generation for repetitive glue, and standardize on data-first pipelines (parse → transform → evaluate). Many teams get the benefits simply by making intermediate representations explicit.

If you like the REPL principle but you’re shipping product features in mainstream stacks, you can also borrow the spirit in tooling: tight iteration loops, snapshots/rollback, and explicit planning before execution. Koder.ai, for instance, includes a planning mode plus snapshots and rollback to keep rapid iteration safer—an operational echo of Lisp’s “change fast, but stay in control.”

McCarthy’s lasting influence is this: programming gets more powerful when we make reasoning itself programmable—and keep the path from idea to executable system as direct as possible.

Symbolic thinking represents concepts and relationships directly (e.g., “customer,” “is-a,” “depends-on,” “if…then…”), then applies rules and transformations to those representations.

It’s most useful when your problem is full of structure, exceptions, and meaning (rules engines, planning, compilers, configuration, workflow logic), not just arithmetic.

McCarthy pushed the idea that reasoning can be expressed as programs—not only calculation.

That perspective shaped:

Lists are a minimal, flexible way to represent “things made of parts.” Because list elements can themselves be lists, you naturally get tree structures.

That makes it easy to:

S-expressions give you one uniform shape for code and data: nested lists.

That uniformity tends to make systems simpler because:

A macro automates repetitive code structure, not just repetitive computation.

Use macros when you want to:

If you only need reusable logic, a function is usually the better choice.

Garbage collection (GC) automatically reclaims memory that’s no longer reachable, which reduces whole categories of bugs (dangling pointers, double frees).

It’s especially helpful when your program creates many short-lived structures (lists/trees/ASTs), because you can prototype and refactor without designing a manual memory-ownership scheme up front.

A REPL shortens the “think → try → observe” loop. You can define a function, run it, tweak it, and rerun immediately.

To adopt the same benefit in non-Lisp stacks:

Related reading: /blog/the-repl-and-fast-feedback-loops

Many modern workflows reuse the same underlying ideas:

map/filter, composition)Even if you never ship Lisp, you likely use Lisp-descended daily.

Common trade-offs include:

The practical approach is to evaluate fit by domain and constraints, not reputation.

Try this 10-minute exercise:

This often reveals where “code-as-data” patterns, rule engines, or DSL-like configs will simplify your system.