Apr 30, 2025·8 min

John Ousterhout: Practical Design, Tcl, and the Cost of Complexity

Explore John Ousterhout’s ideas on practical software design, Tcl’s legacy, the Ousterhout vs Brooks debate, and how complexity sinks products.

Explore John Ousterhout’s ideas on practical software design, Tcl’s legacy, the Ousterhout vs Brooks debate, and how complexity sinks products.

John Ousterhout is a computer scientist and engineer whose work spans both research and real systems. He created the Tcl programming language, helped shape modern file systems, and later distilled decades of experience into a simple, slightly uncomfortable claim: complexity is the primary enemy of software.

That message is still timely because most teams don’t fail due to a lack of features or effort—they fail because their systems (and organizations) become hard to understand, hard to change, and easy to break. Complexity doesn’t just slow down engineers. It leaks into product decisions, roadmap confidence, customer trust, incident frequency, and even hiring—because onboarding becomes a months-long ordeal.

Ousterhout’s framing is practical: when a system accumulates special cases, exceptions, hidden dependencies, and “just this once” fixes, the cost isn’t limited to the codebase. The whole product becomes more expensive to evolve. Features take longer, QA gets harder, releases become riskier, and teams start avoiding improvements because touching anything feels dangerous.

This isn’t a call for academic purity. It’s a reminder that every shortcut has interest payments—and complexity is the highest-interest debt.

To make the idea concrete (and not just motivational), we’ll look at Ousterhout’s message through three angles:

This isn’t written only for language nerds. If you build products, lead teams, or make roadmap tradeoffs, you’ll find actionable ways to spot complexity early, prevent it from becoming institutionalized, and treat simplicity as a first-class constraint—not a nice-to-have after launch.

Complexity isn’t “lots of code” or “hard math.” It’s the gap between what you think the system will do when you change it and what it actually does. A system is complex when small edits feel risky—because you can’t predict the blast radius.

In healthy code, you can answer: “If we change this, what else might break?” Complexity is what makes that question expensive.

It often hides in:

Teams feel complexity as slower shipping (more time spent investigating), more bugs (because behavior is surprising), and brittle systems (changes require coordination across many people and services). It also taxes onboarding: new teammates can’t build a mental model, so they avoid touching core flows.

Some complexity is essential: the business rules, compliance requirements, edge cases in the real world. You can’t delete those.

But a lot is accidental: confusing APIs, duplicated logic, “temporary” flags that become permanent, and modules that leak internal details. This is the complexity that design choices create—and the only kind you can consistently pay down.

Tcl started with a practical goal: make it easy to automate software and extend existing applications without rewriting them. John Ousterhout designed it so teams could add “just enough programmability” to a tool—then hand that power to users, operators, QA, or anyone who needed to script workflows.

Tcl popularized the notion of a glue language: a small, flexible scripting layer that connects components written in faster, lower-level languages. Instead of building every feature into a monolith, you could expose a set of commands, then compose them into new behaviors.

That model proved influential because it matched how work actually happens. People don’t only build products; they build build-systems, test harnesses, admin tools, data converters, and one-off automations. A lightweight scripting layer turns those tasks from “file a ticket” into “write a script.”

Tcl made embedding a first-class concern. You could drop an interpreter into an application, export a clean command interface, and instantly gain configurability and fast iteration.

That same pattern shows up today in plugin systems, configuration languages, extension APIs, and embedded scripting runtimes—whether the script syntax looks like Tcl or not.

It also reinforced an important design habit: separate stable primitives (the host app’s core capabilities) from changeable composition (scripts). When it works, tools evolve faster without constantly destabilizing the core.

Tcl’s syntax and “everything is a string” model could feel unintuitive, and large Tcl codebases sometimes became hard to reason about without strong conventions. As newer ecosystems offered richer standard libraries, better tooling, and larger communities, many teams naturally migrated.

None of that erases Tcl’s legacy: it helped normalize the idea that extensibility and automation aren’t extras—they’re product features that can dramatically reduce complexity for the people using and maintaining a system.

Tcl was built around a deceptively strict idea: keep the core small, make composition powerful, and keep scripts readable enough that people can work together without constant translation.

Rather than shipping a huge set of specialized features, Tcl leaned on a compact set of primitives (strings, commands, simple evaluation rules) and expected users to combine them.

That philosophy nudges designers toward fewer concepts, reused in many contexts. The lesson for product and API design is straightforward: if you can solve ten needs with two or three consistent building blocks, you shrink the surface area people must learn.

A key trap in software design is optimizing for the builder’s convenience. A feature can be easy to implement (copy an existing option, add a special flag, patch a corner case) while making the product harder to use.

Tcl’s emphasis was the opposite: keep the mental model tight, even if the implementation has to do more work behind the scenes.

When you review a proposal, ask: does this reduce the number of concepts a user must remember, or does it add one more exception?

Minimalism only helps when primitives are consistent. If two commands look similar but behave differently in edge cases, users end up memorizing trivia. A small set of tools can become “sharp edges” when rules vary subtly.

Think of a kitchen: a good knife, pan, and oven let you make many meals by combining techniques. A gadget that only slices avocados is a one-off feature—easy to sell, but it clutters drawers.

Tcl’s philosophy argues for the knife and pan: general tools that compose cleanly, so you don’t need a new gadget for every new recipe.

In 1986, Fred Brooks wrote an essay with an intentionally provocative conclusion: there is no single breakthrough—no “silver bullet”—that will make software development an order of magnitude faster, cheaper, and more reliable in one leap.

His point wasn’t that progress is impossible. It was that software is already a medium where we can do almost anything, and that freedom carries a unique burden: we’re constantly defining the thing as we build it. Better tools help, but they don’t erase the hardest part of the work.

Brooks split complexity into two buckets:

Tools can crush accidental complexity. Think of what we gained from higher-level languages, version control, CI, containers, managed databases, and good IDEs. But Brooks argued that essential complexity dominates, and it doesn’t disappear just because the tooling improves.

Even with modern platforms, teams still spend most of their energy negotiating requirements, integrating systems, handling exceptions, and keeping behavior consistent over time. The surface area may change (cloud APIs instead of device drivers), but the core challenge remains: translating human needs into precise, maintainable behavior.

This sets up the tension that Ousterhout leans into: if essential complexity can’t be eliminated, can disciplined design meaningfully reduce how much of it leaks into the code—and into developers’ heads day to day?

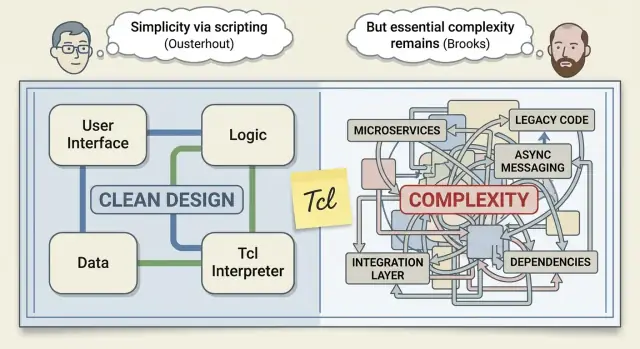

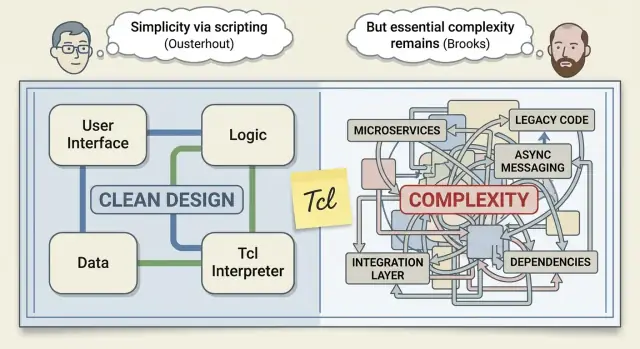

People sometimes frame “Ousterhout vs Brooks” as a fight between optimism and realism. It’s more useful to read it as two experienced engineers describing different parts of the same problem.

Brooks’s “No Silver Bullet” argues there’s no single breakthrough that will magically remove the hard part of software. Ousterhout doesn’t really dispute that.

His pushback is narrower and practical: teams often treat complexity as inevitable when a lot of it is self-inflicted.

In Ousterhout’s view, good design can reduce complexity meaningfully—not by making software “easy,” but by making it less confusing to change. That’s a big claim, and it matters because confusion is what turns everyday work into slow work.

Brooks focuses on what he calls essential difficulty: software must model messy realities, changing requirements, and edge cases that exist outside the codebase. Even with great tools and smart people, you can’t delete that. You can only manage it.

They overlap more than the debate suggests:

Instead of asking “Who’s right?”, ask: Which complexity can we control this quarter?

Teams can’t control market changes or the core difficulty of the domain. But they can control whether new features add special cases, whether APIs force callers to remember hidden rules, and whether modules hide complexity or leak it.

That’s the actionable middle ground: accept essential complexity, and be relentlessly selective about the accidental kind.

A deep module is a component that does a lot, while exposing a small, easy-to-understand interface. The “depth” is the amount of complexity the module takes off your plate: callers don’t need to know the messy details, and the interface doesn’t force them to.

A shallow module is the opposite: it may wrap a small bit of logic, but it pushes complexity outward—through lots of parameters, special flags, required call order, or “you must remember to…” rules.

Think of a restaurant. A deep module is the kitchen: you order “pasta” from a simple menu and don’t care about supplier choices, boiling times, or plating.

A shallow module is a “kitchen” that hands you raw ingredients with a 12-step instruction sheet and asks you to bring your own pan. The work still happens—but it moved to the customer.

Extra layers can be great if they collapse many decisions into one obvious choice.

For example, a storage layer that exposes save(order) and handles retries, serialization, and indexing internally is deep.

Layers hurt when they mostly rename things or add options. If a new abstraction introduces more configuration than it removes—say, save(order, format, retries, timeout, mode, legacyMode)—it’s likely shallow. The code may look “organized,” but the cognitive load shows up in every call site.

useCache, skipValidation, force, legacy.Deep modules don’t just “encapsulate code.” They encapsulate decisions.

A “good” API isn’t just one that can do a lot. It’s one that people can hold in their heads while they work.

Ousterhout’s design lens pushes you to judge an API by the mental effort it demands: how many rules you must remember, how many exceptions you must predict, and how easy it is to accidentally do the wrong thing.

Human-friendly APIs tend to be small, consistent, and hard to misuse.

Small doesn’t mean underpowered—it means the surface area is concentrated into a few concepts that compose well. Consistent means the same pattern works across the whole system (parameters, error handling, naming, return types). Hard to misuse means the API guides you into safe paths: clear invariants, validation at boundaries, and types or runtime checks that fail early.

Every extra flag, mode, or “just in case” configuration becomes a tax on all users. Even if only 5% of callers need it, 100% of callers must now learn it exists, wonder whether they need it, and interpret behavior when it interacts with other options.

This is how APIs accumulate hidden complexity: not in any single call, but in the combinatorics.

Defaults are a kindness: they let most callers omit decisions and still get sensible behavior. Conventions (one obvious way to do it) reduce branching in the user’s mind. Naming does real work too: choose verbs and nouns that match user intent, and keep similar operations named similarly.

One more reminder: internal APIs matter as much as public ones. Most complexity in products lives behind the scenes—service boundaries, shared libraries, and “helper” modules. Treat those interfaces like products, with reviews and versioning discipline (see also /blog/deep-modules).

Complexity rarely arrives as a single “bad decision.” It accumulates through small, reasonable-looking patches—especially when teams are under deadline pressure and the immediate goal is to ship.

One trap is feature flags everywhere. Flags are useful for safe rollouts, but when they linger, each flag multiplies the number of possible behaviors. Engineers stop reasoning about “the system” and start reasoning about “the system, except when flag A is on and the user is in segment B.”

Another is special-case logic: “Enterprise customers need X,” “Except in region Y,” “Unless the account is older than 90 days.” These exceptions often spread across the codebase, and after a few months nobody knows which are still required.

A third is leaky abstractions. An API that forces callers to understand internal details (timing, storage format, caching rules) pushes complexity outward. Instead of one module carrying the burden, every caller learns the quirks.

Tactical programming is optimizing for this week: quick fixes, minimal changes, “just patch it.”

Strategic programming optimizes for the next year: small redesigns that prevent the same class of bugs and reduce future work.

The danger is “maintenance interest.” A quick workaround feels cheap now, but you pay it back with interest: slower onboarding, fragile releases, and fear-driven development where nobody wants to touch the old code.

Add lightweight prompts to code review: “Does this add a new special case?” “Can the API hide this detail?” “What complexity are we leaving behind?”

Keep short decision records for non-trivial tradeoffs (a few bullets is enough). And reserve a small refactor budget each sprint so strategic fixes aren’t treated as extracurricular work.

Complexity doesn’t stay trapped in engineering. It leaks into schedules, reliability, and the way customers experience your product.

When a system is hard to understand, every change takes longer. Time-to-market slips because each release requires more coordination, more regression testing, and more “just to be safe” review cycles.

Reliability suffers too. Complex systems create interactions no one can fully predict, so bugs show up as edge cases: the checkout fails only when a coupon, a saved cart, and a regional tax rule combine in a particular way. Those are the incidents that are hardest to reproduce and slowest to fix.

Onboarding becomes a hidden drag. New teammates can’t build a useful mental model, so they avoid touching risky areas, copy patterns they don’t understand, and unintentionally add more complexity.

Customers don’t care whether a behavior is caused by a “special case” in the code. They experience it as inconsistency: settings that don’t apply everywhere, flows that change depending on how you arrived, features that work “most of the time.”

Trust drops, churn rises, and adoption stalls.

Support teams pay for complexity through longer tickets and more back-and-forth to gather context. Operations pays through more alerts, more runbooks, and more careful deployments. Every exception becomes something to monitor, document, and explain.

Imagine requests for “one more notification rule.” Adding it seems quick, but it introduces another branch in behavior, more UI copy, more test cases, and more ways users can misconfigure things.

Now compare that to simplifying the existing notification flow: fewer rule types, clearer defaults, and consistent behavior across web and mobile. You may ship fewer knobs, but you reduce surprises—making the product easier to use, easier to support, and faster to evolve.

Treat complexity like performance or security: something you plan for, measure, and protect. If you only notice complexity when delivery slows down, you’re already paying interest.

Alongside feature scope, define how much new complexity a release is allowed to introduce. The budget can be simple: “no net-new concepts unless we remove one,” or “any new integration must replace an old pathway.”

Make tradeoffs explicit in planning: if a feature requires three new configuration modes and two exception cases, that should “cost” more than a feature that fits existing concepts.

You don’t need perfect numbers—just signals that trend in the right direction:

Track these per release, and tie them to decisions: “We added two new public options; what did we remove or simplify to compensate?”

Prototypes are often judged by “Can we build it?” Instead, use them to answer: “Does this feel simple to use and hard to misuse?”

Have someone unfamiliar with the feature attempt a realistic task with the prototype. Measure time-to-success, questions asked, and where they make wrong assumptions. Those are complexity hotspots.

This is also where modern build workflows can reduce accidental complexity—if they keep iteration tight and make it easy to reset mistakes. For example, when teams use a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai to sketch an internal tool or a new flow via chat, features like planning mode (to clarify intent before generation) and snapshots/rollback (to undo risky changes quickly) can make early experimentation feel safer—without committing to a pile of half-finished abstractions. If the prototype graduates, you can still export source code and apply the same “deep module” and API discipline described above.

Make “complexity cleanup” work periodic (quarterly or once per major release), and define what “done” means:

The goal isn’t cleaner code in the abstract—it’s fewer concepts, fewer exceptions, and safer change.

Here are a few moves that translate Ousterhout’s “complexity is the enemy” idea into week-by-week team habits.

Pick one subsystem that regularly causes confusion (onboarding pain, recurring bugs, lots of “how does this work?” questions).

Internal follow-ups you can run: a “complexity review” in planning (/blog/complexity-review) and a quick check on whether your tooling is reducing accidental complexity rather than adding layers (/pricing).

What one piece of complexity would you remove first if you could only delete a single special case this week?

Complexity is the gap between what you expect will happen when you change the system and what actually happens.

You feel it when small edits seem risky because you can’t predict the blast radius (tests, services, configs, customers, or edge cases you might break).

Look for signals that reasoning is expensive:

Essential complexity comes from the domain (regulations, real-world edge cases, core business rules). You can’t remove it—only model it well.

Accidental complexity is self-inflicted (leaky abstractions, duplicated logic, too many modes/flags, unclear APIs). This is the part teams can reliably reduce through design and simplification work.

A deep module does a lot while exposing a small, stable interface. It “absorbs” messy details (retries, formats, ordering, invariants) so callers don’t have to.

A practical test: if most callers can use the module correctly without knowing internal rules, it’s deep; if callers must memorize rules and sequences, it’s shallow.

Common symptoms:

legacy, skipValidation, force, mode).Prefer APIs that are:

When you’re tempted to add “just one more option,” first ask whether you can redesign the interface so most callers don’t need to think about that choice at all.

Use feature flags for controlled rollout, then treat them as debt with an end date:

Long-lived flags multiply the number of “systems” engineers must reason about.

Make complexity explicit in planning, not just in code review:

The goal is to force tradeoffs into the open before complexity becomes institutionalized.

Tactical programming optimizes for this week: quick patches, minimal change, “ship it.”

Strategic programming optimizes for the next year: small redesigns that remove recurring classes of bugs and reduce future work.

A useful heuristic: if a fix requires caller knowledge (“remember to call X first” or “set this flag in prod only”), you probably need a more strategic change to hide that complexity inside the module.

Tcl’s lasting lesson is the power of a small set of primitives plus strong composition—often as an embedded “glue” layer.

Modern equivalents include:

The design goal is the same: keep the core simple and stable, and let change happen through clean interfaces.

Shallow modules often look organized but move complexity outward to every caller.