Oct 11, 2025·8 min

Kafka event streaming: when a queue works and when a log wins

Kafka event streaming changed system design by treating events as an ordered log. Learn when a simple queue is enough, and when logs pay off.

Why teams hit a wall with traditional integrations

Most products start with simple point-to-point integrations: System A calls System B, or a small script copies data from one place to another. It works until the product grows, teams split up, and the number of connections multiplies. Soon every change needs coordination across several services, because one small field or status update can ripple through a chain of dependencies.

Speed is usually the first thing to break. Adding a new feature means updating multiple integrations, redeploying several services, and hoping nothing else depended on the old behavior.

Then debugging gets painful. When something looks wrong in the UI, it’s hard to answer basic questions: what happened, in what order, and which system wrote the value you’re seeing?

The missing piece is often an audit trail. If data is pushed directly from one database to another (or transformed along the way), you lose the history. You might see the final state, but not the sequence of events that led there. Incident reviews and customer support both suffer because you can’t replay the past to confirm what changed and why.

This is also where the “who owns the truth” argument starts. One team says, “The billing service is the source of truth.” Another says, “The order service is.” In reality, each system has a partial view, and point-to-point integrations turn that disagreement into everyday friction.

A simple example: an order is created, then paid, then refunded. If three systems update each other directly, each one can end up with a different story when retries, timeouts, or manual fixes happen.

That leads to the core design question behind Kafka event streaming: do you just need to move work from one place to another (a queue), or do you need a shared, durable record of what happened that many systems can read, rewind, and trust (a log)? The answer changes how you build, debug, and evolve your system.

Jay Kreps, Kafka, and the idea of the log

Jay Kreps helped shape Kafka and, more importantly, the way many teams think about data movement. The useful shift is mindset: stop treating messages as one-off deliveries, and start treating system activity as a record.

The core idea is simple. Model important changes as a stream of immutable facts:

- An order was created.

- A payment was authorized.

- A user changed their email.

Each event is a fact that shouldn’t be edited after the fact. If something changes later, you add a new event that states the new truth. Over time, those facts form a log: an append-only history of your system.

This is where Kafka event streaming differs from many basic messaging setups. A lot of queues are built around “send it, process it, delete it.” That’s fine when work is purely a handoff. The log view says, “keep the history so many consumers can use it, now and later.”

Replaying history is the practical superpower.

If a report is wrong, you can re-run the same event history through a fixed analytics job and see where the numbers changed. If a bug caused wrong emails, you can replay events into a test environment and reproduce the exact timeline. If a new feature needs past data, you can build a new consumer that starts from the beginning and catches up at its own pace.

Here’s a concrete example. Imagine you add fraud checks after you already processed months of payments. With a log of payment and account events, you can replay the past to train or calibrate rules on real sequences, compute risk scores for old transactions, and backfill “fraud_review_requested” events without rewriting your database.

Notice what this forces you to do. A log-based approach pushes you to name events clearly, keep them stable, and accept that multiple teams and services will depend on them. It also forces useful questions: What is the source of truth? What does this event mean long-term? What do we do when we made a mistake?

The value isn’t the personality. It’s realizing that a shared log can become the memory of your system, and memory is what lets systems grow without breaking every time you add a new consumer.

Queue vs log: the simplest mental model

A message queue is like a to-do line for your software. Producers put work into the line, consumers take the next item, do the work, and the item is gone. The system is mainly about getting each task handled once, as soon as possible.

A log is different. It’s an ordered record of facts that happened, kept in a durable sequence. Consumers don’t “take” events away. They read the log at their own pace, and they can read it again later. In Kafka event streaming, that log is the core idea.

A practical way to remember the difference:

- Queue = work to be done. Once a worker confirms it, it disappears.

- Log = history of what happened. Events stick around for a retention period.

Retention changes the design. With a queue, if you later need a new feature that depends on old messages (analytics, fraud checks, replays after a bug), you often have to add a separate database or start capturing extra copies somewhere else. With a log, replay is normal: you can rebuild a derived view by reading from the beginning (or from a known checkpoint).

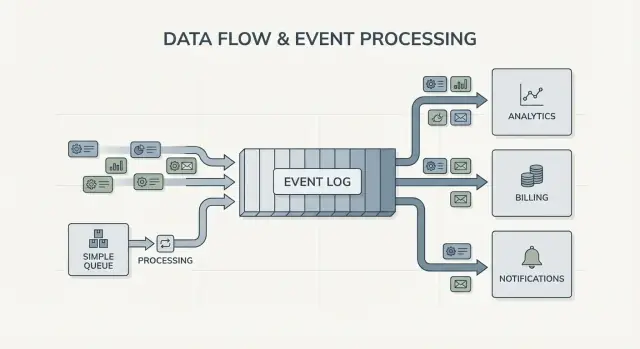

Fan-out is another big difference. Imagine a checkout service emits “OrderPlaced.” With a queue, you usually pick one worker group to process it, or you duplicate work across multiple queues. With a log, billing, email, inventory, search indexing, and analytics can all read the same event stream independently. Each team can move at its own speed, and adding a new consumer later doesn’t require changing the producer.

So the mental model is straightforward: use a queue when you’re moving tasks; use a log when you’re recording events that multiple parts of the company may want to read, now or later.

What event streaming changes in system design

Event streaming flips the default question. Instead of asking, “Who should I send this message to?”, you start by recording “What just happened?” That sounds small, but it changes how you model your system.

You publish facts like OrderPlaced or PaymentFailed, and other parts of the system decide if, when, and how they react.

With Kafka event streaming, producers stop needing a list of direct integrations. A checkout service can publish one event, and it doesn’t need to know whether analytics, email, fraud checks, or a future recommendation service will use it. New consumers can appear later, older ones can be paused, and the producer still behaves the same.

This also changes how you recover from mistakes. In a message-only world, once a consumer misses something or has a bug, the data is often “gone” unless you built custom backups. With a log, you can fix the code and replay the history to rebuild the correct state. That often beats manual database edits or one-off scripts that nobody trusts.

In practice, the shift shows up in a few reliable ways: you treat events as a durable record, you add features by subscribing instead of modifying producers, you can rebuild read models (search indexes, dashboards) from scratch, and you get clearer timelines of what happened across services.

Observability improves because the event log becomes a shared reference. When something goes wrong, you can follow a business sequence: order created, inventory reserved, payment retried, shipment scheduled. That timeline is often easier to understand than scattered application logs because it’s focused on business facts.

A concrete example: if a discount bug mis-priced orders for two hours, you can ship a fix and replay the affected events to recompute totals, update invoices, and refresh analytics. You’re correcting outcomes by re-deriving results, not guessing which tables to patch by hand.

When a simple queue is enough

Draft Events That Age Well

Draft stable event names and fields, then generate code to publish and consume.

A simple queue is the right tool when you’re moving work, not building a long-term record. The goal is to hand off a task to a worker, run it, and then forget it. If nobody needs to replay the past, inspect old events, or add new consumers later, a queue keeps things simpler.

Queues shine for background jobs: sending signup emails, resizing images after upload, generating a nightly report, or calling an external API that can be slow. In these cases the message is just a work ticket. Once a worker finishes the job, the ticket has done its job too.

A queue also fits the usual ownership model: one consumer group is responsible for doing the work, and other services are not expected to read the same message independently.

A queue is usually enough when most of these are true:

- The data has short-lived value.

- One team or one service owns the job end-to-end.

- Replays and long retention aren’t requirements.

- Debugging doesn’t depend on re-running history.

Example: a product uploads user photos. The app writes a “resize image” task to a queue. Worker A picks it up, creates thumbnails, stores them, and marks the task done. If the task runs twice, the output is the same (idempotent), so at-least-once delivery is fine. No other service needs to read that task later.

If your needs start drifting toward shared facts (many consumers), replay, audit, or “what did the system believe last week?”, that’s where Kafka event streaming and a log-based approach start paying off.

When a log-based approach pays off

A log-based system pays off when events stop being a one-time message and start being shared history. Instead of “send it and forget it,” you keep an ordered record that many teams can read, now or later, at their own pace.

The clearest signal is multiple consumers. One event like “OrderPlaced” can feed billing, email, fraud checks, search indexing, and analytics. With a log, each consumer reads the same stream independently. You don’t have to build a custom fan-out pipeline or coordinate who gets the message first.

Another win is being able to answer, “What did we know then?” If a customer disputes a charge, or a recommendation looked wrong, an append-only history makes it possible to replay the facts as they arrived. That audit trail is hard to bolt onto a simple queue later.

You also gain a practical way to add new features without rewriting old ones. If you add a new “shipping status” page months later, a new service can subscribe and backfill from existing history to build its state, instead of asking other systems for exports.

A log-based approach is often worth it when you recognize one or more of these needs:

- The same events must feed several systems (analytics, search, billing, support tools).

- You need replay, auditing, or investigations based on past facts.

- New services must backfill from history without one-off jobs.

- Ordering matters per entity (per order, per user).

- Event formats will evolve and you need a controlled way to handle versioning.

A common pattern is a product that starts with orders and emails. Later, finance wants revenue reports, product wants funnels, and ops wants a live dashboard. If each new need forces you to copy data through a new pipeline, costs show up quickly. A shared event log lets teams build on the same source of truth, even as the system grows and event shapes change.

How to decide, step by step

Plan Backfills Early

Model backfills by reprocessing stored records in a test run before shipping changes.

Choosing between a simple queue and a log-based approach is easier when you treat it like a product decision. Start from what you need to be true a year from now, not just what works this week.

A practical 5-step decision

-

Map the publishers and readers. Write down who creates events and who reads them today, then add likely future consumers (analytics, search indexing, fraud checks, customer notifications). If you expect many teams to read the same events independently, a log starts to make sense.

-

Ask whether you’ll need to reread history. Be specific about why: replay after a bug, backfills, or consumers that read at different speeds. Queues are great for handing off work once. Logs are better when you want a record you can replay.

-

Define what “done” means. For some workflows, done means “the job ran” (send an email, resize an image). For others, done means “the event is a durable fact” (an order was placed, a payment was authorized). Durable facts push you toward a log.

-

Pick delivery expectations and decide how you’ll handle duplicates. At-least-once delivery is common, which means duplicates can happen. If a duplicate could hurt (double-charging a card), plan for idempotency: store a processed event ID, use unique constraints, or make updates safe to repeat.

-

Start with one thin slice. Choose one event stream that’s easy to reason about and grow from there. If you go with Kafka event streaming, keep the first topic focused, name events clearly, and avoid mixing unrelated event types.

A concrete example: if “OrderPlaced” will later feed shipping, invoicing, support, and analytics, a log lets each team read at its own pace and replay after mistakes. If you only need a background worker to send a receipt email, a simple queue is usually enough.

Example: order events in a growing product

Imagine a small online store. At first it only needs to take orders, charge a card, and create a shipping request. The easiest version is one background job that runs after checkout: “process order.” It talks to the payments API, updates the order row in the database, then calls shipping.

That queue style works well when there’s one clear workflow, you only need one consumer (the worker), and retries and dead letters cover most failure cases.

It starts to hurt as the store grows. Support wants automatic “where is my order?” updates. Finance wants daily revenue numbers. The product team wants customer emails. A fraud check should happen before shipping. With a single “process order” job, you end up editing the same worker again and again, adding branches, and risking new bugs in the core flow.

With a log-based approach, checkout produces small facts as events, and each team can build on them. Typical events might look like:

- OrderPlaced

- PaymentConfirmed

- ItemShipped

- RefundIssued

The key change is ownership. The checkout service owns OrderPlaced. The payments service owns PaymentConfirmed. Shipping owns ItemShipped. Later, new consumers can appear without changing the producer: a fraud service reads OrderPlaced and PaymentConfirmed to score risk, an email service sends receipts, analytics builds funnels, and support tools keep a timeline of what happened.

This is where Kafka event streaming pays off: the log keeps history, so new consumers can rewind and catch up from the beginning (or from a known point) instead of asking every upstream team to add another webhook.

The log still doesn’t replace your database. You still need a database for the current state: the latest order status, the customer record, inventory counts, and transactional rules (like “don’t ship unless payment is confirmed”). Think of the log as the record of changes and the database as the place you query for “what is true right now.”

Common mistakes and traps

Define Event Ownership

Clarify who owns each fact and reduce point to point coupling as you grow.

Event streaming can make systems feel cleaner, but a few common mistakes can erase the benefits fast. Most of them come from treating an event log like a remote control instead of a record.

A frequent trap is writing events as commands, like “SendWelcomeEmail” or “ChargeCardNow.” That makes consumers tightly coupled to your intent. Events work better as facts: “UserSignedUp” or “PaymentAuthorized.” Facts age well. New teams can reuse them later without guessing what you meant.

Duplicates and retries are the next big source of pain. In real systems, producers retry and consumers reprocess. If you don’t plan for it, you get double charges, double emails, and angry support tickets. The fix isn’t exotic, but it must be deliberate: idempotent handlers, stable event IDs, and business rules that detect “already applied.”

Common pitfalls:

- Using command-style events that tell services what to do instead of recording what happened.

- Building consumers that break if they see the same event twice.

- Splitting streams too early, so a single business flow is scattered across too many topics.

- Ignoring schema rules until a small change breaks older consumers.

- Treating streaming as a substitute for good database design.

Schema and versioning deserve special attention. Even if you start with JSON, you still need a clear contract: required fields, optional fields, and how changes roll out. A small change like renaming a field can quietly break analytics, billing, or mobile apps that update slower.

Another trap is over-splitting. Teams sometimes create a new stream for every feature. A month later, no one can answer “What is the current state of an order?” because the story is spread across too many places.

Event streaming doesn’t remove the need for solid data models. You still need a database that represents the current truth. The log is history, not your whole application.

Quick checklist and next steps

If you’re stuck choosing between a queue and Kafka event streaming, start with a few fast checks. They’ll tell you whether you need a simple handoff between workers, or a log you can reuse for years.

Quick checks

- Do you need replay (for backfills, bug fixes, or new features), and how far back?

- Will more than one consumer need the same events now or soon (analytics, search, emails, fraud, billing)?

- Do you need retention so teams can re-read history without asking the producer to resend?

- How important is ordering, and at what level: per entity (per order, per user) or truly global?

- Can consumers be idempotent (safe to retry the same event without double-charging, double-emailing, or double-updating)?

If you answered “no” to replay, “one consumer only,” and “short-lived messages,” a basic queue is usually enough. If you answered “yes” to replay, multiple consumers, or longer retention, a log-based approach tends to pay off because it turns one stream of facts into a shared source other systems can build on.

Next steps

Turn the answers into a small, testable plan.

- List 5-10 core events in plain language (example: OrderPlaced, PaymentAuthorized, OrderShipped) and note who publishes and who consumes each.

- Decide the ordering key (often per entity, like orderId) and document what “correct order” means.

- Define an idempotency rule per consumer (for example: store the last processed event ID per order).

- Pick a retention target that matches your needs (days for a queue-like workflow, weeks/months when replay matters).

- Run one end-to-end slice in a sandbox before you commit the whole system.

If you’re prototyping fast, you can sketch the event flow in Koder.ai planning mode and iterate on the design before you lock in event names and retry rules. Since Koder.ai supports source code export, snapshots, and rollback, it’s also a practical way to test a single producer-consumer slice and adjust event shapes without turning early experiments into production debt.

FAQ

What’s the simplest way to explain “queue vs log”?

A queue is best for work tickets you want handled and then forgotten (send an email, resize an image, run a job). A log is best for facts you want to keep and let many systems read and replay later (order placed, payment authorized, refund issued).

How do I know my point-to-point integrations are becoming a problem?

You’ll feel it when every new feature requires touching multiple integrations, and debugging turns into “who wrote this value?” with no clear timeline. A log helps because it becomes a shared record you can inspect and replay instead of guessing from scattered database states.

When does a log-based approach (Kafka-style) actually pay off?

When you need an audit trail and replay: fixing a bug by reprocessing history, backfilling a new feature from old data, running investigations like “what did we know at the time?”, or supporting multiple consumers (billing, analytics, support, fraud) without changing the producer each time.

Why does the “source of truth” argument get worse as systems grow?

Because systems fail in messy ways: retries, timeouts, partial outages, and manual fixes. If each service updates others directly, they can disagree about what happened. An append-only event history gives you one ordered sequence to reason about, even if some consumers were down and catch up later.

What should an event look like if I want it to age well?

Model events as immutable facts (past tense) that describe something that already happened:

OrderPlaced, notProcessOrderPaymentAuthorized, notChargeCardNowUserEmailChanged, notUpdateEmail

If something changes, publish a new event that states the new truth instead of editing the old one.

How do I prevent duplicate events from causing real damage?

Assume duplicates will happen (at-least-once delivery is common). Make each consumer safe to retry by:

- Using a stable event ID and storing “already processed” markers

- Enforcing unique constraints where possible

- Designing updates so applying the same event twice doesn’t create double side effects (like double charges)

Default rule: correctness first, speed second.

How should I evolve event schemas without breaking consumers?

Prefer additive changes: keep old fields, add new optional fields, and avoid renaming/removing fields that existing consumers rely on. If you must make a breaking change, version the event (or topic/stream) and migrate consumers intentionally rather than “just updating JSON.”

What’s a good first step if I’m switching from a queue mindset to a log mindset?

Start with one thin, end-to-end slice:

- Pick a single business flow (for example,

OrderPlaced→ email receipt). - Define clear event names and required fields.

- Choose the ordering key (often

orderIdoruserId). - Make the consumer idempotent.

- Set retention long enough to replay during testing.

Prove the loop works before expanding to more events and teams.

Does an event log replace my database?

No. Keep a database for current state and transactions (“what’s true right now”). Use the event log for history and for rebuilding derived views (analytics tables, search indexes, timelines). A practical split is: DB for reads/writes in the product, log for distribution, replay, and audit.

How can Koder.ai help me prototype an event-streaming design safely?

Planning mode is useful for mapping publishers/consumers, defining event names, and deciding idempotency and retention before you write production code. Then you can implement a small producer-consumer slice, take snapshots, and roll back quickly while you adjust event shapes. When it’s stable, export the source code and deploy like any other service.