Apr 19, 2025·8 min

Kelsey Hightower’s Cloud-Native Clarity: Kubernetes Explained

How Kelsey Hightower’s clear teaching style helped teams understand Kubernetes and operations concepts, shaping confidence, shared language, and wider adoption.

How Kelsey Hightower’s clear teaching style helped teams understand Kubernetes and operations concepts, shaping confidence, shared language, and wider adoption.

Cloud-native tools promise speed and flexibility, but they also introduce new vocabulary, new moving parts, and new ways of thinking about operations. When the explanation is fuzzy, adoption slows down for a simple reason: people can’t confidently connect the tool to the problems they actually have. Teams hesitate, leaders delay decisions, and early experiments turn into half-finished pilots.

Clarity changes that dynamic. A clear explanation turns “Kubernetes explained” from a marketing phrase into a shared understanding: what Kubernetes does, what it doesn’t do, and what your team is responsible for day to day. Once that mental model is in place, conversations get practical—about workloads, reliability, scaling, security, and the operational habits needed to run production systems.

When concepts are explained in plain language, teams:

In other words, communication isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s part of the rollout plan.

This piece focuses on how Kelsey Hightower’s style of teaching made core DevOps concepts and Kubernetes fundamentals feel approachable—and how that approach influenced broader cloud-native adoption. You’ll leave with lessons you can apply inside your own organization:

The goal isn’t to debate tools. It’s to show how clear communication—repeated, shared, and improved by a community—can move an industry from curiosity to confident use.

Kelsey Hightower is a well-known Kubernetes educator and community voice whose work has helped many teams understand what container orchestration actually involves—especially the operational parts people tend to learn the hard way.

He’s been visible in practical, public roles: speaking at industry conferences, publishing tutorials and talks, and participating in the broader cloud-native community where practitioners share patterns, failures, and fixes. Rather than positioning Kubernetes as a magic product, his output tends to treat it as a system you operate—one with moving pieces, tradeoffs, and real failure modes.

What consistently stands out is empathy for the people on the hook when things break: on-call engineers, platform teams, SREs, and developers trying to ship while learning new infrastructure.

That empathy shows up in how he explains:

It also shows in the way he speaks to beginners without talking down to them. The tone is usually direct, grounded, and careful with claims—more “here’s what happens under the hood” than “here’s the one best way.”

You don’t need to treat anyone as a mascot to see the impact. The evidence is in the material itself: widely referenced talks, hands-on learning resources, and explanations that get reused by other educators and internal platform teams. When people say they “finally got” a concept like control planes, certificates, or cluster bootstrapping, it’s often because someone explained it plainly—and a lot of those plain explanations trace back to his teaching style.

If Kubernetes adoption is partly a communication problem, his influence is a reminder that clear teaching is a form of infrastructure too.

Before Kubernetes became the default answer to “how do we run containers in production?”, it often felt like a dense wall of new vocabulary and assumptions. Even teams already comfortable with Linux, CI/CD, and cloud services found themselves asking basic questions—then feeling like they shouldn’t have to.

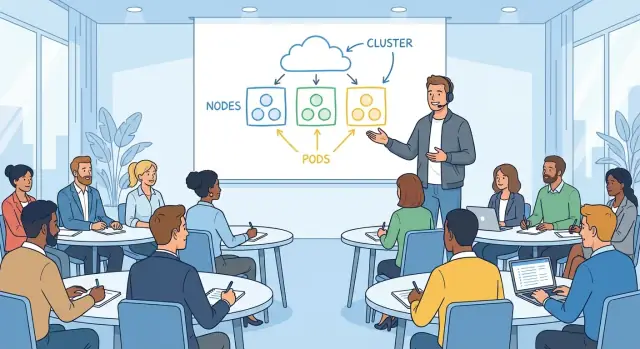

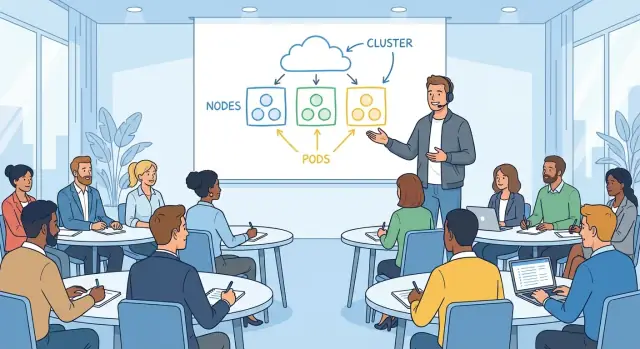

Kubernetes introduced a different way of thinking about applications. Instead of “a server runs my app,” you suddenly had pods, deployments, services, ingresses, controllers, and clusters. Each term sounded simple on its own, but the meaning depended on how it connected to the rest.

A common sticking point was mental model mismatch:

This wasn’t just learning a tool; it was learning a system that treats infrastructure as fluid.

The first demo might show a container scaling up smoothly. The anxiety started later, when people imagined the real operational questions:

Many teams weren’t afraid of YAML—they were afraid of hidden complexity, where mistakes could be silent until an outage.

Kubernetes was often presented as a neat platform where you “just deploy” and everything is automated. In practice, getting to that experience required choices: networking, storage, identity, policies, monitoring, logging, and upgrade strategy.

That gap created frustration. People weren’t rejecting Kubernetes itself; they were reacting to how hard it was to connect the promise (“simple, portable, self-healing”) to the steps required to make it true in their environment.

Kelsey Hightower teaches like someone who has been on call, had a deploy go sideways, and still had to ship the next day. The goal isn’t to impress with vocabulary—it’s to help you build a mental model you can use at 2 a.m. when a pager is ringing.

A key habit is defining terms at the moment they matter. Instead of dropping a paragraph of Kubernetes vocabulary up front, he explains a concept in context: what a Pod is in the same breath as why you’d group containers, or what a Service does when the question is “how do requests find my app?”

This approach reduces the “I’m behind” feeling many engineers get with cloud-native topics. You don’t need to memorize a glossary; you learn by following a problem to its solution.

His explanations tend to start with something tangible:

Those questions naturally lead to Kubernetes primitives, but they’re anchored in scenarios engineers recognize from real systems. Diagrams still help, but they’re not the whole lesson—the example does the heavy lifting.

Most importantly, the teaching includes the unglamorous parts: upgrades, incidents, and trade-offs. It’s not “Kubernetes makes it easy,” it’s “Kubernetes gives you mechanisms—now you need to operate them.”

That means acknowledging constraints:

This is why his content resonates with working engineers: it treats production as the classroom, and clarity as a form of respect.

“Kubernetes the Hard Way” is memorable not because it’s difficult for the sake of being difficult, but because it makes you touch the parts most tutorials hide. Instead of clicking through a managed service wizard, you assemble a working cluster piece by piece. That “learning by doing” approach turns infrastructure from a black box into a system you can reason about.

The walkthrough has you create the building blocks yourself: certificates, kubeconfigs, control plane components, networking, and worker node setup. Even if you never plan to run Kubernetes this way in production, the exercise teaches what each component is responsible for and what can go wrong when it’s misconfigured.

You don’t just hear “etcd is important”—you see why it matters, what it stores, and what happens if it’s unavailable. You don’t just memorize “the API server is the front door”—you configure it and understand which keys it checks before letting requests through.

Many teams feel uneasy adopting Kubernetes because they can’t tell what’s happening under the hood. Building from basics flips that feeling. When you understand the chain of trust (certs), the source of truth (etcd), and the control loop idea (controllers constantly reconciling desired vs. actual state), the system feels less mysterious.

That trust is practical: it helps you evaluate vendor features, interpret incidents, and choose sane defaults. You can say “we know what this managed service is abstracting,” instead of hoping it’s correct.

A good walkthrough breaks “Kubernetes” into small, testable steps. Each step has a clear expected outcome—service starts, a health check passes, a node joins. Progress is measurable, and mistakes are local.

That structure lowers anxiety: complexity becomes a series of understandable decisions, not a single leap into the unknown.

A lot of Kubernetes confusion comes from treating it like a pile of features instead of a simple promise: you describe what you want, and the system keeps trying to make reality match it.

“Desired state” is just your team writing down the outcome you expect: run three copies of this app, expose it on a stable address, limit how much CPU it can use. It’s not a step-by-step runbook.

That distinction matters because it mirrors everyday ops work. Instead of “SSH to server A, start process, copy config,” you declare the target and let the platform handle the repetitive steps.

Reconciliation is the constant check-and-fix loop. Kubernetes compares what’s running right now with what you asked for, and if something drifted—an app crashed, a node disappeared, a config changed—it takes action to close the gap.

In human terms: it’s an on-call engineer who never sleeps, continuously re-applying the agreed standard.

This is also where separating concepts from implementation details helps. The concept is “the system corrects drift.” The implementation might involve controllers, replica sets, or rollout strategies—but you can learn those later without losing the core idea.

Scheduling answers a practical question every operator recognizes: which machine should run this workload? Kubernetes looks at available capacity, constraints, and policies, then places work on nodes.

Connecting primitives to familiar tasks makes it click:

Once you frame Kubernetes as “declare, reconcile, place,” the rest becomes vocabulary—useful, but no longer mysterious.

Operations talk can sound like a private language: SLIs, error budgets, “blast radius,” “capacity planning.” When people feel excluded, they either nod along or avoid the topic entirely—both outcomes lead to fragile systems.

Kelsey’s style makes ops feel like normal engineering: a set of practical questions you can learn to ask, even if you’re new.

Instead of treating operations as abstract “best practices,” translate it into what your service must do under pressure.

Reliability becomes: What breaks first, and how will we notice? Capacity becomes: What happens on Monday morning traffic? Failure modes become: Which dependency will lie to us, time out, or return partial data? Observability becomes: If a customer complains, can we answer “what changed” in five minutes?

When ops concepts are phrased this way, they stop sounding like trivia and start sounding like common sense.

Great explanations don’t claim there’s one correct path—they show the cost of each choice.

Simplicity vs. control: a managed service may reduce toil, but it can limit low-level tuning.

Speed vs. safety: shipping quickly might mean fewer checks today, but it increases the chance you’ll debug production tomorrow.

By naming trade-offs plainly, teams can disagree productively without shaming someone for “not getting it.”

Operations are learned by observing real incidents and near-misses, not by memorizing terminology. A healthy ops culture treats questions as work, not weakness.

One practical habit: after an outage or scary alert, write down three things—what you expected to happen, what actually happened, and what signal would have warned you earlier. That small loop turns confusion into better runbooks, clearer dashboards, and calmer on-call rotations.

If you want this mindset to spread, teach it the same way: plain words, honest trade-offs, and permission to learn out loud.

Clear explanations don’t just help one person “get it.” They travel. When a speaker or writer makes Kubernetes feel concrete—showing what each piece does, why it exists, and where it fails in real life—those ideas get repeated in hallway chats, copied into internal docs, and re-taught at meetups.

Kubernetes has a lot of terms that sound familiar but mean something specific: cluster, node, control plane, pod, service, deployment. When explanations are precise, teams stop arguing past each other.

A few examples of how shared vocabulary shows up:

That alignment speeds up debugging, planning, and onboarding because people spend less time translating.

Many engineers avoid Kubernetes at first not because they can’t learn it, but because it feels like a black box. Clear teaching replaces mystery with a mental model: “Here’s what talks to what, here’s where state lives, here’s how traffic gets routed.”

Once the model clicks, experimentation feels safer. People are more willing to:

When explanations are memorable, the community repeats them. A simple diagram or analogy becomes a default way to teach, and it influences:

Over time, clarity becomes a cultural artifact: the community learns not just Kubernetes, but how to talk about operating it.

Clear communication didn’t just make Kubernetes easier to learn—it changed how organizations decided to adopt it. When complex systems are explained in plain terms, the perceived risk drops, and teams can talk about outcomes instead of jargon.

Executives and IT leaders rarely need every implementation detail, but they do need a credible story about trade-offs. Straightforward explanations of what Kubernetes is (and isn’t) helped frame conversations around:

When Kubernetes was presented as a set of understandable building blocks—rather than a magical platform—budget and timeline discussions became less speculative. That made it easier to run pilots and measure real results.

Industry adoption didn’t spread only through vendor pitches; it spread through teaching. High-signal talks, demos, and practical guides created a shared vocabulary across companies and job roles.

That education typically translated into three adoption accelerators:

Once teams could explain concepts like desired state, controllers, and rollout strategies, Kubernetes became discussable—and therefore adoptable.

Even the best explanations can’t replace organizational change. Kubernetes adoption still demands:

Communication made Kubernetes approachable; successful adoption still required commitment, practice, and aligned incentives.

Kubernetes adoption usually fails for ordinary reasons: people can’t predict how day‑2 operations will work, they don’t know what to learn first, and documentation assumes everyone already speaks “cluster.” The practical fix is to treat clarity as part of the rollout plan—not as an afterthought.

Most teams mix up “how to use Kubernetes” with “how to operate Kubernetes.” Split your enablement into two explicit paths:

Put the split right at the top of your docs so new hires don’t accidentally start in the deep end.

Demos should begin with the smallest working system and add complexity only when it’s necessary to answer a real question.

Start with a single Deployment and Service. Then add configuration, health checks, and autoscaling. Only after the basics are stable should you introduce ingress controllers, service meshes, or custom operators. The goal is for people to connect cause and effect, not memorize YAML.

Runbooks that are pure checklists turn into cargo-cult operations. Every major step should include a one‑sentence rationale: what symptom it addresses, what success looks like, and what could go wrong.

For example: “Restarting the pod clears a stuck connection pool; if it recurs within 10 minutes, check downstream latency and HPA events.” That “why” is what lets someone improvise when the incident doesn’t match the script.

You’ll know your Kubernetes training is working when:

Track these outcomes and adjust your docs and workshops accordingly. Clarity is a deliverable—treat it like one.

One underrated way to make Kubernetes and platform concepts “click” is to let teams experiment with realistic services before they touch critical environments. That can mean building a small internal reference app (API + UI + database), then using it as the consistent example in docs, demos, and troubleshooting drills.

Platforms like Koder.ai can help here because you can generate a working web app, backend service, and data model from a chat-driven spec, then iterate in a “planning mode” mindset before anyone worries about perfect YAML. The point isn’t to replace Kubernetes learning—it’s to shorten the time from idea → running service so your training can focus on the operational mental model (desired state, rollouts, observability, and safe changes).

The fastest way to make “platform” work inside a company is to make it understandable. You don’t need every engineer to become a Kubernetes expert, but you do need shared vocabulary and the confidence to debug basic issues without panic.

Define: Start with one clear sentence. Example: “A Service is a stable address for a changing set of Pods.” Avoid dumping five definitions at once.

Show: Demonstrate the concept in the smallest possible example. One YAML file, one command, one expected outcome. If you can’t show it quickly, the scope is too big.

Practice: Give a short task people can do themselves (even in a sandbox). “Scale this Deployment and watch what happens to the Service endpoint.” Learning sticks when hands touch the tools.

Troubleshoot: End by breaking it on purpose and walking through how you’d think. “What would you check first: events, logs, endpoints, or network policy?” This is where operational confidence grows.

Analogies are useful for orientation, not precision. “Pods are like cattle, not pets” can explain replaceability, but it can also hide important details (stateful workloads, persistent volumes, disruption budgets).

A good rule: use the analogy to introduce the idea, then quickly switch to the real terms. Say, “It’s like X in one way; here’s where it stops being like X.” That one sentence prevents misconceptions that become expensive later.

Before you present, validate four things:

Consistency beats occasional big training. Try lightweight rituals:

When teaching becomes normal, adoption becomes calmer—and your platform stops feeling like a black box.

Cloud-native stacks add new primitives (pods, services, control planes) and new operational responsibilities (upgrades, identity, networking). When teams don’t share a clear mental model, decisions stall and pilots stay half-finished because people can’t connect the tool to their real risks and workflows.

Because plain language makes trade-offs and prerequisites visible early:

He’s widely listened to because he consistently explains Kubernetes as an operable system, not a magic product. His teaching emphasizes what breaks, what you’re responsible for, and how to reason about the control plane, networking, and security—topics teams typically learn during incidents if they’re not taught up front.

Early confusion usually comes from a mental-model shift:

Once teams accept that “infrastructure is fluid,” the vocabulary becomes easier to place.

It’s the gap between demos and production reality. Demos show “deploy and scale,” but production forces decisions about:

Without that context, Kubernetes feels like a promise without a map.

It teaches fundamentals by having you assemble a cluster piece by piece (certificates, kubeconfigs, control plane components, networking, worker setup). Even if you’ll use a managed service in production, doing the “hard way” once helps you understand what’s being abstracted and where failures and misconfigurations tend to show up.

It means you describe outcomes, not step-by-step procedures. Examples:

Kubernetes continuously works to keep reality aligned with that description, even when pods crash or nodes disappear.

Reconciliation is the constant check-and-fix loop: Kubernetes compares what you asked for with what’s actually running, then takes action to close gaps.

Practically, it’s why a crashed pod comes back and why scaling settings keep being enforced over time—even when the system changes underneath.

Define them as everyday questions tied to real pressure:

This keeps ops from sounding like jargon and turns it into normal engineering decision-making.

Split enablement into two explicit tracks:

Then validate learning by outcomes (faster incident triage, fewer repeated questions), not by training attendance.