Oct 02, 2025·8 min

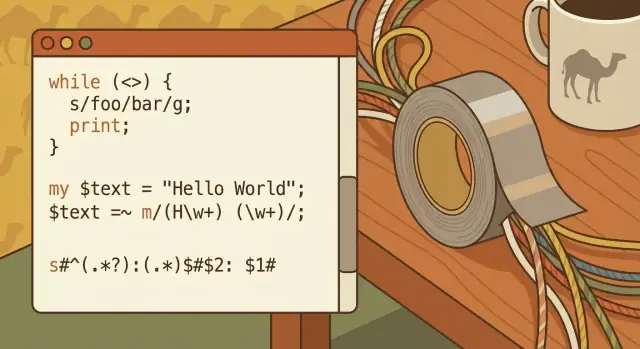

Larry Wall, Perl, and the Duct Tape Mindset for Text Work

How Larry Wall’s “duct tape” philosophy made Perl a web-automation workhorse—and what it still teaches about practical text processing today.

How Larry Wall’s “duct tape” philosophy made Perl a web-automation workhorse—and what it still teaches about practical text processing today.

“Duct tape programming” is the idea that the best tool is often the one that gets your real problem solved quickly—even if the solution isn’t pretty, isn’t permanent, and wasn’t designed as a grand system.

It’s not about doing sloppy work. It’s about valuing momentum when you’re facing messy inputs, incomplete specs, and a deadline that doesn’t care how elegant your architecture diagram is.

The duct tape mindset starts with a simple question: What’s the smallest change that makes the pain go away? That could mean a short script to rename 10,000 files, a quick filter to extract error lines from logs, or a one-off transformation that turns a chaotic export into something a spreadsheet can read.

This article uses Larry Wall and Perl as a historical story of that attitude in action—but the point isn’t nostalgia. It’s to pull out practical lessons that still apply whenever you work with text, logs, CSVs, HTML snippets, or “data” that is really just a pile of inconsistent strings.

If you’re not a professional programmer but you regularly touch:

…you’re exactly the audience.

By the end, you should have four clear takeaways:

Larry Wall didn’t set out to invent a “clever” language. He was a working engineer and system administrator who spent his days wrangling unruly text: log files, reports, configuration snippets, mail headers, and ad‑hoc data dumps that never quite matched the format the manual promised.

By the mid‑1980s, Unix already had excellent tools—sh, grep, sed, awk, pipes, and filters. But real jobs rarely fit into a single tidy command. You’d start with a pipeline, then discover you needed a small state machine, better string handling, a reusable script, and a way to keep it readable enough that you could fix it next week.

Larry’s motivation was practical: reduce the friction of “glue work,” the unglamorous but constant task of connecting tools and transforming text until something useful falls out.

Perl’s original goal was not to replace Unix tools—it was to make them easier to orchestrate when a one‑liner pipeline turned into a mini program. Instead of jumping between multiple utilities (each with its own quoting rules and edge cases), Perl offered one place to:

That’s the “duct tape” mindset: not perfection, but a fast, durable fix that holds things together.

Perl culture embraced a few values that matched that day‑to‑day reality: pragmatism over purity, expressiveness over ceremony, and the famous “There’s more than one way to do it.” Those weren’t slogans for show—they were permission to solve the problem in front of you with the least pain.

Perl’s early popularity can sound mysterious in hindsight. It wasn’t. It simply matched what teams needed at the time: a language that could survive messy input, integrate with existing systems, and let a tired human ship a working script before the next pager alert.

Early web sites weren’t powered by app frameworks and managed services. A lot of them were a web server plus a directory of CGI scripts, a handful of flat files, and maybe a simple database that didn’t yet feel “central” to everything.

Operations were log-heavy: access logs, error logs, upload folders, email inboxes receiving form submissions, and text files that quietly became databases. When something broke, you often diagnosed it by grepping through yesterday’s logs and tweaking a script.

Automation was simply: a repeatable task that runs without someone doing it manually each time.

That task might be triggered by a web request (someone submits a form, clicks “search,” downloads a report), or by a scheduled job (cron runs every hour to rotate logs, rebuild pages, send summaries).

Even small sites needed to:

Doing this manually didn’t just waste time—it introduced errors and delays.

Perl fit neatly between everything that already existed:

grep, sed, awk, sort) that were great at single stepsPerl could read a request, run system commands, transform messy text, and write HTML or update a file—all in one script. That “glue language” role is what made early web automation practical: it connected pieces that were individually useful but awkward to chain together safely and repeatedly.

Perl earned its “duct tape” reputation because it could sit comfortably between classic Unix command-line tools and the new world of web scripting. If your data started as log files, emails, CSV exports, or HTML snippets, Perl could grab it, reshape it, and hand it off—without forcing you to adopt a whole new environment.

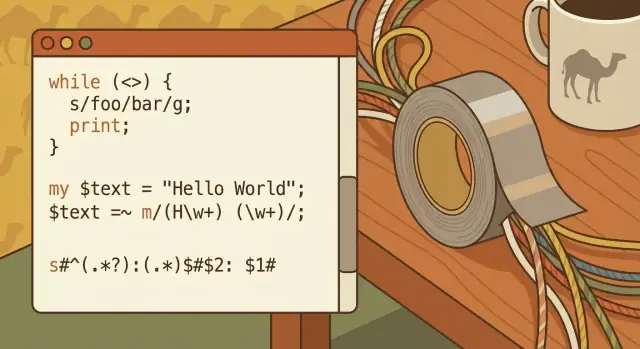

Out of the box, Perl made text manipulation feel unusually direct:

split, join, replace) that map to real cleanup tasksThat combination meant you didn’t need a long toolchain to do everyday parsing and editing.

Unix encourages small, focused programs connected together. Perl could be one of those pieces: read from standard input, transform the text, and print the result for the next tool in the chain.

A common mental model was:

read → transform → write

For example: read server logs, normalize a date format, remove noise, then write a cleaned file—possibly piping into sort, uniq, or grep before or after. Perl didn’t replace Unix tools; it glued them together when the “awk + sed + shell” combo started getting awkward.

That same script-first approach carried into early web development. A Perl script could accept form input, process it like any other text stream, and print HTML as output—making it a practical bridge between system utilities and web pages.

Because Perl ran across many Unix-like systems, teams could often move the same script between machines with minimal changes—valuable when deployments were simple, manual, and frequent.

Regular expressions (often shortened to “regex”) are a way to describe text patterns—like a “find and change” tool, but with rules instead of exact words. Instead of searching for the literal string [email protected], regex lets you say “find anything that looks like an email address.” That single shift—from exact match to pattern match—is what made so much early automation possible.

Think of regex as a mini-language for answering questions like:

If you’ve ever copied text into a spreadsheet and wished it would magically split into columns, you’ve wanted regex.

Early web scripts lived on messy inputs: form fields typed by humans, logs produced by servers, and files stitched together from different systems. Regex made it practical to do three high-value jobs quickly:

Validate inputs (e.g., “this seems like a URL,” “this looks like a date”).

Extract fields (e.g., pull the status code and request path out of a log line).

Rewrite content (e.g., normalize phone numbers, replace old links, sanitize user input before saving).

Perl’s regex support didn’t just exist—it was designed to be used constantly. That fit perfectly with the “duct tape” mindset: take inconsistent text, apply a few targeted rules, and get something reliable enough to ship.

Regex shines on the kind of “almost structured” text people deal with every day:

12/26/25 to 2025-12-26, or recognizing multiple date styles.Regex is powerful enough to become cryptic. A short, clever pattern can be hard to review, hard to debug, and easy to break later when the input format changes.

A maintainable approach is to keep patterns small, add comments (where the language supports it), and prefer two clear steps over one “genius” expression when someone else will need to touch it next month.

Perl one-liners are best thought of as tiny scripts: small, single-purpose commands you can run directly in your terminal to transform text. They shine when you need a quick cleanup, a one-time migration, or a fast check before you commit to writing a full program.

A one-liner usually reads from standard input, makes a change, and prints the result. For example, removing empty lines from a file:

perl -ne 'print if /\S/' input.txt > output.txt

Or extracting specific “columns” (fields) from space-separated text:

perl -lane 'print "$F[0]\t$F[2]"' data.txt

And for batch renaming, Perl can drive your file operations with a bit more control than a basic rename tool:

perl -e 'for (@ARGV){(my $n=$_)=~s/\s+/_/g; rename $_,$n}' *

(That last one replaces spaces with underscores.)

One-liners are appropriate when:

Write a real script when:

“Quick” shouldn’t mean “untraceable.” Save your shell history line (or paste it into a notes file in the repo), include a before/after example, and record what changed and why.

If you run the same one-liner twice, that’s your signal to wrap it into a small script with a filename, comments, and a predictable input/output path.

CPAN (the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network) is, in simple terms, a shared library shelf for Perl: a public collection of reusable modules that anyone can download and use.

Instead of writing every feature from scratch, small teams could grab a well-tested module and focus on their actual problem—shipping a script that worked today.

A lot of everyday web tasks were suddenly within reach of a single developer because CPAN offered building blocks that would otherwise take days or weeks to reinvent. Common examples included:

This mattered because early web automation was often “one more script” added to an already-busy system. CPAN let that script be assembled quickly—and often more safely—by leaning on code that had already been used in the wild.

The tradeoff is real: dependencies are a form of commitment.

Pulling in modules can save time immediately, but it also means you need to think about version compatibility, security fixes, and what happens if a module goes unmaintained. A quick win today can become a confusing upgrade tomorrow.

Before relying on a CPAN module, prefer ones that are clearly maintained:

When CPAN is used thoughtfully, it’s one of the best expressions of the “duct tape” mindset: reuse what works, keep moving, and don’t build infrastructure you don’t need.

CGI (Common Gateway Interface) was the “just run a program” phase of the web. A request hit the server, the server launched your Perl script, your script read inputs (often from environment variables and STDIN), and then printed a response—usually an HTTP header and a blob of HTML.

At its simplest, the script:

name=Sam&age=42)Content-Type: text/html) and then HTMLThat model made it easy to ship something useful quickly. It also made it easy to ship something risky quickly.

Perl CGI became the shortcut for practical web automation:

These were often small-team wins: one script, one URL, immediate value.

Because CGI scripts execute per request, small mistakes multiplied:

Speed is a feature, but only when paired with boundaries. Even quick scripts need clear validation, careful quoting, and predictable output rules—habits that still pay off whether you’re writing a tiny admin tool or a modern web endpoint.

Perl earned a reputation for being hard to read because it made clever solutions easy. Dense punctuation-heavy syntax, lots of context-dependent behavior, and a culture of “there’s more than one way to do it” encouraged short, impressive code. That’s great for a quick fix at 2 a.m.—but six months later, even the original author may struggle to remember what a one-liner was really doing.

The maintainability problem isn’t that Perl is uniquely unreadable—it’s that Perl lets you compress intent until it disappears. Common culprits include tightly packed regular expressions with no comments, heavy use of implicit variables like $_, and smart-looking tricks (side effects, nested ternaries, magical defaults) that save lines but cost understanding.

A few habits drastically improve readability without slowing you down:

Perl’s community normalized simple guardrails that many languages later adopted as defaults: enable use strict; and use warnings;, write basic tests (even a few sanity checks), and document assumptions with inline comments or POD.

These practices don’t make code “enterprise”—they make it survivable.

The broader lesson applies to any language: write for your future self and your teammates. The fastest script is the one that can be safely changed when requirements inevitably shift.

Text work hasn’t gotten cleaner—it’s just moved around. You might not be maintaining CGI scripts, but you’re still wrangling CSV exports, SaaS webhooks, log files, and “temporary” integration feeds that become permanent. The same practical skills that made Perl useful still save time (and prevent quiet data corruption).

Most problems aren’t “hard parsing,” they’re inconsistent input:

1,234 vs 1.234, dates like 03/04/05, month names in different languages.Treat every input as untrusted, even if it comes from “our system.” Normalize early: pick an encoding (usually UTF‑8), standardize newlines, trim obvious noise, and convert to a consistent schema.

Then validate assumptions explicitly: “this file has 7 columns,” “IDs are numeric,” “timestamps are ISO‑8601.” When something breaks, fail loudly and record what you saw (sample line, row number, source file).

When you can, prefer clear formats and real parsers over clever splitting. If you’re given JSON, parse JSON. If you’re given CSV, use a CSV parser that understands quoting. Guessing works right up until a customer name contains a comma.

These skills pay off in everyday tasks: filtering application logs during an incident, cleaning finance exports, transforming CRM imports, bridging API integrations, and doing one-time data migrations where “almost correct” is still wrong.

Perl’s “duct tape” reputation wasn’t about being sloppy—it was about being useful. That legacy shows up every time a team needs a small script to reconcile exports, normalize logs, or reshape a pile of semi-structured text into something a spreadsheet or database can digest.

Modern scripting often defaults to Python, Ruby, or JavaScript (Node.js). Their high-level roles overlap: quick automation, integration with other systems, and glue code between tools.

Perl’s classic strengths were (and still are) direct access to the operating system, expressive text manipulation, and a culture of “just get the job done.” Python tends to emphasize readability and a wide standard library; Ruby often shines in developer ergonomics and web-centric conventions; JavaScript brings ubiquity and easy deployment anywhere Node runs.

A lot of today’s work is shaped by frameworks, stable APIs, cloud services, and better tooling. Tasks that once required custom scripts now have managed services, hosted queues, and off-the-shelf connectors.

Deployment is also different: containers, CI pipelines, and dependency pinning are expected, not optional.

Real-world text is still messy. Logs contain surprises, exports contain “creative” formatting, and data still needs careful transformation to be reliable.

That’s the enduring lesson Perl taught: the unglamorous 80% of automation is parsing, cleaning, validating, and producing predictable output.

The best choice is usually the one your team can maintain: comfort with the language, a healthy ecosystem, and realistic deployment constraints (what’s installed, what security allows, what ops can support). Perl’s legacy isn’t “always use Perl”—it’s “choose the tool that fits the mess you actually have.”

It’s also worth noting that the “duct tape” instinct is showing up in modern AI-assisted workflows. For example, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can be useful when you need a quick internal tool (say, a log viewer, a CSV normalizer, or a small admin UI) and you’d rather iterate via chat than scaffold everything by hand. The same caution still applies: ship fast, but keep the result readable, testable, and easy to roll back if today’s “temporary” fix becomes tomorrow’s critical path.

Perl’s biggest gift isn’t a specific syntax—it’s a working attitude toward messy text problems. When you’re about to automate something (a rename job, a log cleanup, a data import), use this “duct tape” checklist to stay pragmatic without creating a future headache.

Start small:

^ / $), groups, character classes, and “greedy vs. non-greedy” matching.Include: inputs, outputs, a couple of before/after examples, assumptions (encoding, separators), and a rollback plan (“restore from backup X” or “re-run with previous version”).

Perl is both a historical pillar of web-era text work and a continuing teacher: be practical, be careful, and leave a script that another human can trust.

It’s a pragmatic approach: use the smallest effective change that solves the real pain quickly, especially with messy inputs and incomplete specs.

It’s not permission to be sloppy. The “duct tape” part is about getting to a working result, then adding just enough safety (tests, backups, notes) so the fix doesn’t become a trap later.

Use the “one more time” rule: if you run the same manual cleanup twice, automate it.

Good candidates include:

If the task affects production data, add guardrails (dry run, backups, validation) before you execute.

Treat one-liners as tiny scripts:

If it grows long, needs error handling, or will be reused, promote it to a real script with arguments and clear input/output paths.

Regex is best when the text is “almost structured” (logs, emails, IDs, inconsistent separators) and you need to validate, extract, or rewrite patterns.

To keep it maintainable:

A quick fix becomes “forever” when it’s used repeatedly, depended on by others, or embedded in a workflow (cron, pipelines, docs).

Signals it’s time to harden it:

At that point: add validation, logging, tests, and a clear README describing assumptions.

CPAN can save days, but every dependency is a commitment.

Practical selection checklist:

Also plan deployment: pin versions, document install steps, and track security updates.

The biggest CGI-era lesson is: speed without boundaries creates vulnerabilities.

If you accept input from users or other systems:

These habits apply equally to modern scripts, serverless functions, and web endpoints.

Common pitfalls include:

Normalize early (encoding, newlines), validate assumptions (column counts, required fields), and fail loudly with a sample of the offending row/line.

Rule of thumb: if it’s a real format, use a real parser.

Regex and ad-hoc splitting are best for pattern extraction and lightweight cleanup—until an edge case (like a comma in a name) silently corrupts your results.

Choose the tool your team can run and maintain under your real constraints:

Perl’s legacy here is the decision principle: pick the tool that fits the mess you actually have, not the architecture you wish you had.