Aug 08, 2025·8 min

Leonard Adleman and RSA: How the Internet Learned to Trust

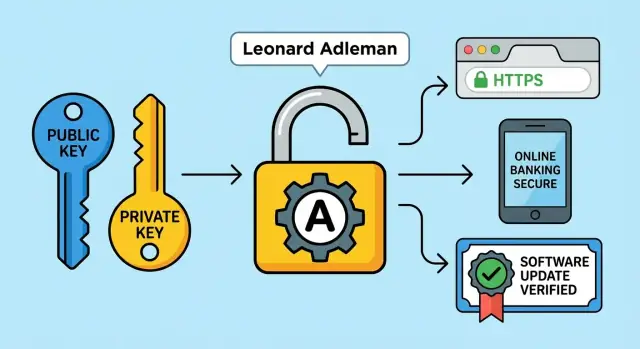

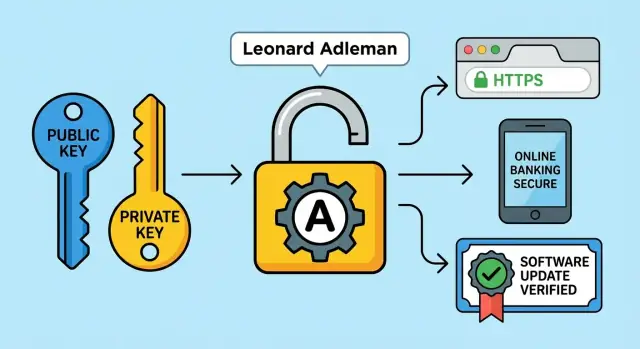

Leonard Adleman helped create RSA, a public-key system that enabled HTTPS, online banking, and signed updates. Learn how it works and why it matters.

Leonard Adleman helped create RSA, a public-key system that enabled HTTPS, online banking, and signed updates. Learn how it works and why it matters.

When people say they “trust” a website or an online service, they usually mean three practical things:

RSA became famous because it helped make those promises possible at internet scale.

You’ve felt RSA’s impact even if you’ve never heard the name. It’s closely tied to how:

The common thread is trust without having to personally know (or pre-arrange secrets with) every server and software vendor you interact with.

This article keeps the explanations simple: no heavy math, and no need for a computer science background. We’ll focus on the everyday “why it works” view.

RSA popularized a powerful approach: instead of one shared secret, you use a public key you can share openly and a private key you keep secret. That split makes it possible to protect privacy and prove identity in situations where people and systems have never met before.

Leonard Adleman is the “A” in RSA, alongside Ron Rivest and Adi Shamir. While Rivest and Shamir are often credited for the core construction, Adleman’s contribution was essential: he helped shape the system into something that was not just clever, but convincing—an algorithm people could analyze, test, and trust.

A big part of Adleman’s role was pressure-testing the idea. In cryptography, a scheme isn’t valuable because it sounds plausible; it’s valuable because it survives careful attacks and scrutiny. Adleman worked on validation, helped refine assumptions, and contributed to the early framing of why RSA should be hard to break.

Just as importantly, he helped translate “this might work” into “this is a cryptosystem others can evaluate.” That clarity—making the design understandable enough for the wider research community to inspect—was crucial for adoption.

Before RSA, secure communication usually depended on both parties already sharing a secret key. That approach works within closed groups, but it doesn’t scale when strangers need to communicate safely (for example, a shopper and a website meeting for the first time).

RSA changed that story by popularizing a practical public-key cryptosystem: you can publish one key for others to use, while keeping a separate private key secret.

RSA’s influence is bigger than one algorithm. It made two internet essentials feel feasible at scale:

Those ideas underpin how HTTPS, online banking, and signed software updates became normal expectations rather than rare exceptions.

Before RSA, secure communication mostly meant shared-secret encryption: both sides had to possess the same secret key ahead of time. That works for a small group, but it breaks down quickly when you try to run a public service used by millions.

If every customer needs a unique secret key to talk to a bank, the bank must generate, deliver, store, rotate, and protect an enormous number of secrets. The hardest part isn’t the math—it’s the coordination.

How do you safely deliver the secret key to each person in the first place? Mailing it is slow and risky. Telling it over the phone can be intercepted or socially engineered. Sending it over the internet defeats the purpose, because the channel is exactly what you’re trying to secure.

Imagine two strangers—say, you and an online store—who have never met. You want to send a payment securely. With shared-secret encryption, you’d need a private key you both already know. But you don’t.

RSA’s breakthrough was enabling secure communication without pre-sharing a secret. Instead, you can publish one key (a public key) that anyone can use to protect a message to you, while keeping another key (a private key) that only you hold.

Even if you could encrypt messages, you still need to know who you’re encrypting to. Otherwise, an attacker can impersonate the bank or store, trick you into using their key, and quietly read or alter everything.

That’s why secure internet communication needs two properties:

RSA helped make both possible, laying the groundwork for how online trust works at scale.

Public-key cryptography is a simple idea with big consequences: you can lock something for someone without first agreeing on a shared secret. That’s the core shift RSA helped make practical.

Think of a public key as a lock you’re happy to hand out to anyone. People can use it to protect a message for you—or (in signature systems) to check that something really came from you.

A private key is the one thing you must keep to yourself. It’s the key that opens what was locked with your public key, and it’s also what lets you create signatures that only you could have made.

Together, the public key and private key form a key pair. They’re mathematically connected, but not interchangeable. Sharing the public key is safe because knowing it doesn’t give someone a practical way to derive the private key.

Encryption is about privacy. If someone encrypts a message with your public key, only your private key can decrypt it.

Digital signatures are about trust and integrity. If you sign something with your private key, anyone with your public key can verify two things:

The security isn’t magic—it relies on hard math problems that are easy to do one way and extremely difficult to reverse with current computers. That “one-way” property is what makes sharing the public key safe while keeping the private key powerful.

RSA is built around a simple asymmetry: it’s easy to do the “forward” math to lock something, but extremely hard to reverse that math to unlock it—unless you have a special secret.

Think of RSA as a kind of mathematical padlock. Anyone can use the public key to lock a message. But only the person holding the private key can unlock it.

What makes this possible is a carefully chosen relationship between the two keys. They’re generated together, and while they’re related, you can’t realistically derive the private key just by looking at the public one.

At a high level, RSA relies on the fact that multiplying large prime numbers is easy, but working backward—figuring out which primes were multiplied—is extremely difficult when the numbers are huge.

For small numbers, factoring is quick. For the sizes used in real RSA keys (thousands of bits), the best known methods still require an impractical amount of time and computing power. That “hard to reverse” property is what keeps attackers from reconstructing the private key.

RSA is usually not used to encrypt large files or long messages directly. Instead, it commonly protects small secrets—most notably a randomly generated session key. That session key then encrypts the real data using faster symmetric encryption, which is better suited for bulk traffic.

RSA is famous because it can do two related—but very different—jobs: encryption and digital signatures. Mixing them up is a common source of confusion.

Encryption mainly targets confidentiality. Digital signatures mainly target integrity + authenticity.

With RSA encryption, someone uses your public key to lock something so that only your private key can unlock it.

In practice, RSA is often used to protect a small secret, like a randomly generated session key. That session key then encrypts the bulk data efficiently.

With RSA signatures, the direction flips: the sender uses their private key to create a signature, and anyone with the public key can verify:

Digital signatures show up in everyday “approval” moments:

Encryption keeps secrets; signatures keep trust.

The padlock in your browser is a shortcut for one idea: your connection to this website is encrypted and (usually) authenticated. It means other people on the network—like someone on public Wi‑Fi—can’t read or silently change what your browser and the site send each other.

It does not mean the website is “safe” in every sense. The padlock can’t tell you whether a store is honest, whether a download is malware, or whether you typed the right domain name. It also doesn’t guarantee the site will protect your data once it reaches their servers.

When you visit an HTTPS site, your browser and the server run a setup conversation called the TLS handshake:

Historically, RSA was often used to exchange the session key (the browser encrypts a secret with the server’s RSA public key). In many modern TLS configurations, RSA is used mainly for authentication via signatures (proving the server controls the private key), while key agreement is done with other methods.

RSA is great for establishing trust and protecting small pieces of data during setup, but it’s slow compared to symmetric encryption. After the handshake, HTTPS switches to fast symmetric algorithms for the actual page loads, logins, and banking transactions.

Online banking has a simple promise: you should be able to log in, review balances, and move money without someone else learning your credentials—or quietly changing what you submit.

A banking session has to protect three things at once:

Without HTTPS, anyone on the same Wi‑Fi, a compromised router, or a malicious network operator could potentially eavesdrop or tamper with traffic.

HTTPS (via TLS) secures the connection so that data moving between your browser and the bank is encrypted and integrity-checked. In practical terms, that means:

RSA’s historical role was crucial here because it helped solve the “first contact” problem: establishing a secure session over an insecure network.

Encryption alone isn’t enough if you’re encrypting to the wrong party. Online banking only works if your browser can tell it’s talking to the real bank, not an impostor site or a man-in-the-middle.

Banks still add MFA, device checks, and fraud monitoring. These reduce damage when credentials are stolen—but they don’t replace HTTPS. They work best as backstops on top of a connection that’s already private and tamper-resistant.

Software updates are a trust problem as much as a technical one. Even if an app is written carefully, an attacker can target the delivery step—swapping a legitimate installer for a modified one, or slipping a tampered update into the path between the publisher and the user. Without a reliable way to authenticate what you downloaded, “update available” can become an easy entry point.

If updates are only protected by a download link, an attacker who compromises a mirror, hijacks a network connection, or tricks a user into visiting a look‑alike page can serve a different file with the same name. The user may install it normally, and the damage can be “silent”: malware bundled with the update, backdoors added to the program, or security settings weakened.

Code signing uses public‑key cryptography (including RSA in many systems) to attach a digital signature to an installer or update package.

The publisher signs the software with a private key. Your device (or operating system) verifies that signature using the publisher’s public key—often delivered via a certificate chain. If even one byte is altered, verification fails. This shifts trust from “where did I download it?” to “can I verify who created it and that it’s intact?”

In modern app delivery pipelines, these same ideas extend beyond installers to things like API calls, build artifacts, and deployment rollouts. For example, platforms such as Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform for shipping web, backend, and mobile apps from a chat interface) still rely on the same foundations: HTTPS/TLS for data in transit, careful certificate handling for custom domains, and practical rollback-style workflows (snapshots and restore points) to reduce risk when pushing changes.

Signed updates reduce the number of unnoticed tampering opportunities. Users get clearer warnings when something is off, and automated update systems can reject altered files before they run. It’s not a guarantee that the software itself is bug‑free, but it’s a powerful defense against impersonation and supply‑chain meddling.

To go deeper on how signatures, certificates, and verification fit together, see /blog/code-signing-basics.

If RSA gives you a public key, a natural question follows: whose public key is it?

A certificate is the internet’s answer. It’s a small, signed data file that connects a public key to an identity—like a website name (example.com), an organization, or a software publisher. Think of it as an ID card for a key: it says “this key belongs to this name,” and it includes details like the certificate’s owner, the public key itself, and validity dates.

Certificates matter because they’re signed by someone else. That “someone” is usually a Certificate Authority (CA).

A CA is a third party that checks certain proofs (which can range from basic domain control to deeper business verification) and then signs the certificate. Your browser or operating system ships with a built-in list of trusted CAs. When you visit a site over HTTPS, your device uses that list to decide whether to accept the certificate’s claim.

This system isn’t perfect: CAs can make mistakes, and attackers can try to trick or compromise them. But it creates a practical chain of trust that works at global scale.

Certificates expire on purpose. Short lifetimes limit damage if a key is stolen and encourage regular maintenance.

Certificates can also be revoked before they expire. Revocation is a way to say, “Stop trusting this certificate,” for example if a private key may have leaked or the certificate was issued incorrectly. Devices can check revocation status (with varying reliability and strictness), which is one reason key hygiene still matters.

Keep your private key private: store it in secure key storage, restrict access, and avoid copying it between systems unless necessary.

Rotate keys when needed—after an incident, during planned upgrades, or when policy requires it. And track expiration dates so renewals don’t become last-minute emergencies.

RSA is a foundational idea, but it’s not a magic shield. Most real-world breaks don’t happen because someone “solved RSA”—they happen because systems around RSA fail.

A few patterns show up again and again:

RSA’s safety depends on generating keys that are large enough and truly unpredictable. Good randomness is essential: if key generation uses a weak random number source, attackers can sometimes reproduce or narrow down the possible keys. Likewise, key length matters because improvements in computing power and math techniques steadily reduce the margin of safety for small keys.

RSA operations are heavier than modern alternatives, which is why many protocols use RSA sparingly—often for authentication or exchanging a temporary secret, then switch to faster symmetric encryption for bulk data.

Security works best as defense-in-depth: protect private keys (ideally in hardware), monitor certificate issuance, patch systems, use phishing-resistant authentication, and design for safe key rotation. RSA is one tool in the chain—not the whole chain.

RSA is one of the most widely supported cryptographic tools on the internet. Even if a service doesn’t “prefer” RSA anymore, it often keeps RSA compatibility because it’s everywhere: older devices, long-lived enterprise systems, and certificate infrastructures built over many years.

Cryptography evolves for the same reasons other security tech does:

You’ll commonly see alternatives in TLS and modern applications:

Plainly: RSA can do both encryption and signatures, but newer systems often split the work—using one method optimized for signatures and another optimized for establishing session keys.

No. RSA is still heavily supported and remains a valid choice in many contexts, especially where compatibility is crucial or where existing certificate and key-management practices are built around it. The “best” option depends on factors like device support, performance needs, compliance requirements, and how keys are stored and rotated.

If you want to see how these choices show up in real HTTPS connections, the next step is: /blog/ssl-tls-explained.

RSA helped make internet-scale trust practical by enabling public-key cryptography, which supports:

Those building blocks are central to HTTPS, online banking, and signed software updates.

Leonard Adleman helped turn RSA from a clever idea into a cryptosystem others could analyze and trust. Practically, that meant pressure-testing assumptions, refining the presentation, and strengthening the argument for why breaking RSA should be hard under realistic attack models.

A public key is meant to be shared; people use it to encrypt something to you or to verify your signatures.

A private key must stay secret; it’s used to decrypt what was encrypted to you (in RSA-encryption setups) and to create signatures that only you could produce.

If the private key leaks, attackers can impersonate you and/or decrypt protected secrets depending on how the key is used.

RSA security relies (at a high level) on a one-way math problem: multiplying large primes is easy, but factoring the resulting huge number back into primes is extremely hard at real key sizes.

The public and private keys are mathematically related, but the relationship is designed so the public key doesn’t reveal the private key in any practical way.

They solve different trust goals:

A common rule of thumb: encryption keeps secrets; signatures prove who sent something and that it wasn’t altered.

In a simplified HTTPS/TLS flow:

RSA may be used for authentication (signatures), and historically was also used to help protect the initial session secret in some configurations.

No. The padlock mainly indicates the connection is encrypted and typically authenticated.

It does not guarantee:

Treat HTTPS as a necessary transport safety layer, not a full trust verdict.

A certificate binds a public key to an identity (like a domain name). Browsers trust that binding because a Certificate Authority (CA) signs the certificate, and browsers/OSes ship with a trusted CA list.

If you’re deploying services, plan for:

Signed updates let your device verify two things:

This defends against “swap the package” attacks (compromised mirrors, hijacked networks, look-alike download pages). For a deeper primer, see /blog/code-signing-basics.

Common real-world failures are usually operational, not “RSA math got broken”:

Practical steps: protect private keys (prefer hardware-backed storage), track expirations, rotate keys deliberately, and monitor certificate issuance where possible.