Nov 03, 2025·8 min

Leslie Lamport and Distributed Systems: Time, Order, Correctness

Learn Lamport’s key distributed-systems ideas—logical clocks, ordering, consensus, and correctness—and why they still guide modern infrastructure.

Why Lamport Still Matters for Modern Distributed Systems

Leslie Lamport is one of the rare researchers whose “theoretical” work shows up every time you ship a real system. If you’ve ever operated a database cluster, a message queue, a workflow engine, or anything that retries requests and survives failures, you’ve been living inside problems Lamport helped name and solve.

What makes his ideas stick is that they aren’t tied to a specific technology. They describe the uncomfortable truths that appear whenever multiple machines try to act like one system: clocks disagree, networks delay and drop messages, and failures are normal—not exceptional.

Three themes we’ll use throughout

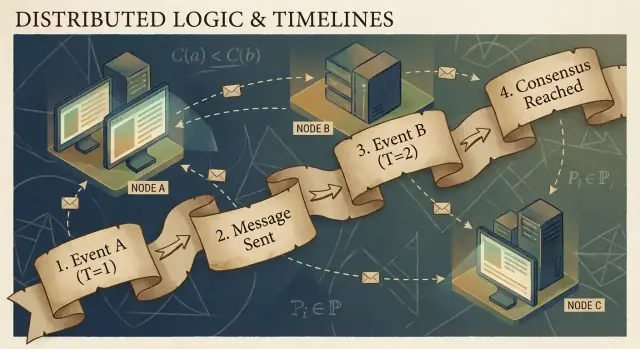

Time: In a distributed system, “what time is it?” is not a simple question. Physical clocks drift, and the order you observe events can differ between machines.

Ordering: Once you can’t trust a single clock, you need other ways to talk about which events happened first—and when you must force everyone to follow the same sequence.

Correctness: “It usually works” is not a design. Lamport pushed the field toward crisp definitions (safety vs. liveness) and specs you can reason about, not just test.

What to expect (no heavy math)

We’ll focus on concepts and intuition: the problems, the minimal tools to think clearly, and how those tools shape practical designs.

Here’s the map:

- Why no shared clock means no single, global story of events

- How causality (“happened-before”) leads to logical clocks and Lamport timestamps

- When partial order isn’t enough and you need one timeline

- How consensus and Paxos relate to agreeing on an order

- Why state machine replication works when ordering is shared

- How to talk about correctness in specs—and how modeling tools like TLA+ help

The Core Problem: No Shared Clock, No Single Reality

A system is “distributed” when it’s made of multiple machines that coordinate over a network to do one job. That sounds simple until you accept two facts: machines can fail independently (partial failures), and the network can delay, drop, duplicate, or reorder messages.

In a single program on one computer, you can usually point to “what happened first.” In a distributed system, different machines can observe different sequences of events—and both can be correct from their local point of view.

Why you can’t trust a global clock

It’s tempting to solve coordination by timestamping everything. But there is no single clock you can rely on across machines:

- Each server’s hardware clock drifts at its own rate.

- Clock synchronization (like NTP) is best-effort, not a guarantee.

- Virtualization, CPU load, or pauses can make time jump or stall.

So “event A happened at 10:01:05.123” on one host doesn’t reliably compare to “10:01:05.120” on another.

How delays scramble reality

Network delays can invert what you think you saw. A write can be sent first but arrive second. A retry can arrive after the original. Two datacenters can process the “same” request in opposite orders.

This makes debugging uniquely confusing: logs from different machines may disagree, and “sorted by timestamp” can create a story that never actually happened.

Real consequences

When you assume a single timeline that doesn’t exist, you get concrete failures:

- Double processing (a payment charged twice after retries)

- Inconsistencies (two users both “successfully” claim the last item)

- Apparent data loss (a later-arriving update overwrites a newer one)

Lamport’s key insight starts here: if you can’t share time, you must reason about order differently.

Causality and the Happened-Before Relation

Distributed programs are made of events: something that happens at a specific node (a process, server, or thread). Examples include “received a request,” “wrote a row,” or “sent a message.” A message is the connector between nodes: one event is a send, another event is the receive.

Lamport’s key insight is that in a system without a reliable shared clock, the most dependable thing you can track is causality—which events could have influenced which other events.

The happened-before relation (→)

Lamport defined a simple rule called happened-before, written as A → B (event A happened before event B):

- Same process order: If A and B occur on the same machine/process, and A is observed to occur first in that process, then A → B.

- Message order: If A is “send message m” and B is “receive message m,” then A → B.

- Transitivity: If A → B and B → C, then A → C.

This relation gives you a partial order: it tells you some pairs are ordered, but not all.

A concrete story: user → request → DB → cache

A user clicks “Buy.” That click triggers a request to an API server (event A). The server writes an order row to the database (event B). After the write completes, the server publishes an “order created” message (event C), and a cache service receives it and updates a cache entry (event D).

Here, A → B → C → D. Even if clocks disagree, the message and program structure create real causal links.

What “concurrent” really means

Two events are concurrent when neither caused the other: not (A → B) and not (B → A). Concurrency doesn’t mean “same time”—it means “no causal path connects them.” That’s why two services can each claim they acted “first,” and both can be correct unless you add an ordering rule.

Logical Clocks: Lamport Timestamps in Plain English

If you’ve ever tried to reconstruct “what happened first” across multiple machines, you’ve hit the basic problem: computers don’t share a perfectly synchronized clock. Lamport’s workaround is to stop chasing perfect time and instead track order.

The idea: a counter attached to each event

A Lamport timestamp is just a number you attach to every meaningful event in a process (a service instance, a node, a thread—whatever you choose). Think of it as an “event counter” that gives you a consistent way to say, “this event happened before that one,” even when wall-clock time is untrustworthy.

The two rules (and they really are that simple)

-

Increment locally: before you record an event (e.g., “wrote to DB”, “sent request”, “appended log entry”), increment your local counter.

-

On receive, take max + 1: when you receive a message that includes the sender’s timestamp, set your counter to:

max(local_counter, received_counter) + 1

Then stamp the receive event with that value.

These rules ensure timestamps respect causality: if event A could have influenced event B (because information flowed via messages), then A’s timestamp will be less than B’s.

What Lamport timestamps can—and can’t—tell you

They can tell you about causal ordering:

- If

TS(A) < TS(B), A might have happened before B. - If A caused B (directly or indirectly), then necessarily

TS(A) < TS(B).

They cannot tell you about real time:

- A lower timestamp does not mean “earlier in seconds.”

- Two events may be concurrent (neither caused the other) and still end up with different timestamps due to message patterns.

So Lamport timestamps are great for ordering, not for measuring latency or answering “what time was it?”

Practical example: ordering log entries across services

Imagine Service A calls Service B, and both write audit logs. You want a unified log view that preserves cause-and-effect.

- Service A increments its counter, logs “starting payment”, sends request to B with timestamp 42.

- Service B receives the request with 42, sets its counter to

max(local, 42) + 1, say 43, and logs “validated card”. - B responds with 44; A receives, updates to 45, and logs “payment completed”.

Now, when you aggregate logs from both services, sorting by (lamport_timestamp, service_id) gives you a stable, explainable timeline that matches the actual chain of influence—even if the wall clocks drifted or the network delayed messages.

From Partial Order to Total Order: When You Need One Timeline

Causality gives you a partial order: some events are clearly “before” others (because a message or dependency connects them), but many events are simply concurrent. That’s not a bug—it’s the natural shape of distributed reality.

Partial order: enough for many questions

If you’re debugging “what could have influenced this?”, or enforcing rules like “a reply must follow its request,” partial order is exactly what you want. You only need to respect happened-before edges; everything else can be treated as independent.

Total order: required when the system must pick one story

Some systems can’t live with “either order is fine.” They need a single sequence of operations, especially for:

- Writes to a shared object (“set balance,” “update profile,” “append to log”)

- Commands that must be applied identically everywhere (state machine replication)

- Conflict resolution where “last write wins” must mean the same thing to every node

Without a total order, two replicas might both be “correct” locally yet diverge globally: one applies A then B, another applies B then A, and you get different outcomes.

How do you get one timeline?

You introduce a mechanism that creates order:

- A sequencer/leader that assigns a monotonically increasing position to each command.

- Or consensus (e.g., Paxos-style approaches) so the cluster agrees on the next log entry even with delays and failures.

The trade-offs you can’t avoid

A total order is powerful, but it costs something:

- Latency: you may wait for coordination before committing.

- Throughput: a single ordered log can become a bottleneck.

- Availability under failures: if you can’t reach enough nodes to agree, progress may pause to protect correctness.

The design choice is simple to state: when correctness requires one shared narrative, you pay coordination costs to get it.

Consensus: Agreeing in the Presence of Delay and Failure

Visualize happened before

Create a timeline view that sorts events by Lamport timestamps for easier debugging.

Consensus is the problem of getting multiple machines to agree on one decision—one value to commit, one leader to follow, one configuration to activate—even though each machine only sees its own local events and whatever messages happen to arrive.

That sounds simple until you remember what a distributed system is allowed to do: messages can be delayed, duplicated, reordered, or lost; machines can crash and restart; and you rarely get a clean signal that “this node is definitely dead.” Consensus is about making agreement safe under those conditions.

Why agreement is tricky

If two nodes temporarily can’t talk (a network partition), each side may try to “move forward” on its own. If both sides decide different values, you can end up with split-brain behavior: two leaders, two different configurations, or two competing histories.

Even without partitions, delay alone causes trouble. By the time a node hears about a proposal, other nodes might have moved on. With no shared clock, you can’t reliably say “proposal A happened before proposal B” just because A has an earlier timestamp—physical time is not authoritative here.

Where you meet consensus in real systems

You might not call it “consensus” day to day, but it shows up in common infrastructure tasks:

- Leader election (who’s in charge right now?)

- Replicated logs (what is the next entry in the shared history?)

- Configuration changes (which set of nodes is allowed to vote/commit?)

In each case, the system needs a single outcome that everyone can converge on, or at least a rule that prevents conflicting outcomes from both being considered valid.

Paxos as Lamport’s answer

Lamport’s Paxos is a foundational solution to this “safe agreement” problem. The key idea isn’t a magic timeout or a perfect leader—it’s a set of rules that ensure only one value can be chosen, even when messages are late and nodes fail.

Paxos separates safety (“never choose two different values”) from progress (“eventually choose something”), making it a practical blueprint: you can tune for real-world performance while keeping the core guarantee intact.

Paxos, Without the Headache: The Key Safety Intuition

Paxos has a reputation for being unreadable, but a lot of that is because “Paxos” isn’t one neat one-liner algorithm. It’s a family of closely related patterns for getting a group to agree, even when messages are delayed, duplicated, or machines temporarily fail.

The cast: proposers, acceptors, and quorums

A helpful mental model is to separate who suggests from who validates.

- Proposers try to get a value chosen (for example: “the next log entry is X”).

- Acceptors vote on proposals.

- A quorum is “enough acceptors” to make progress—typically a majority.

The one structural idea to keep in mind: any two majorities overlap. That overlap is where safety lives.

The safety goal: never decide two different values

Paxos safety is simple to state: once the system decides a value, it must never decide a different one—no split-brain decisions.

The key intuition is that proposals carry numbers (think: ballot IDs). Acceptors promise to ignore older-numbered proposals once they’ve seen a newer one. And when a proposer tries with a new number, it first asks a quorum what they’ve already accepted.

Because quorums overlap, a new proposer will inevitably hear from at least one acceptor that “remembers” the most recently accepted value. The rule is: if anyone in the quorum accepted something, you must propose that value (or the newest among them). That constraint is what prevents two different values from being chosen.

Liveness, at a high level

Liveness means the system eventually decides something under reasonable conditions (for example, a stable leader emerges, and the network eventually delivers messages). Paxos doesn’t promise speed in chaos; it promises correctness, and progress once things calm down.

State Machine Replication: Correctness Through Shared Ordering

Keep full ownership

Ship the generated source code to your repo when the design feels right.

State machine replication (SMR) is the workhorse pattern behind many “high availability” systems: instead of one server making decisions, you run several replicas that all process the same sequence of commands.

The replicated log idea

At the center is a replicated log: an ordered list of commands like “put key=K value=V” or “transfer $10 from A to B.” Clients don’t send commands to every replica and hope for the best. They submit commands to the group, and the system agrees on one order for those commands, then each replica applies them locally.

Why ordering gives you correctness

If every replica starts from the same initial state and executes the same commands in the same order, they will end up in the same state. That’s the core safety intuition: you’re not trying to keep multiple machines “synchronized” by time; you’re making them identical by determinism and shared ordering.

This is why consensus (like Paxos/Raft-style protocols) is so often paired with SMR: consensus decides the next log entry, and SMR turns that decision into a consistent state across replicas.

Where you see it in real systems

- Coordination services (e.g., for configuration and leader election)

- Databases with replicated write-ahead logs

- Message systems that require strict partition ordering

Practical concerns engineers can’t ignore

The log grows forever unless you manage it:

- Snapshots: periodically capture the current state so new nodes can catch up without replaying the entire history.

- Log compaction: safely discard old log entries once they’re reflected in a snapshot and no longer needed.

- Membership changes: adding/removing replicas must be ordered too, otherwise different nodes may disagree about who is “in the group,” leading to split-brain behavior.

SMR isn’t magic; it’s a disciplined way to turn “agreement on order” into “agreement on state.”

Correctness: Safety, Liveness, and Writing a Clear Spec

Distributed systems fail in weird ways: messages arrive late, nodes restart, clocks disagree, and networks split. “Correctness” isn’t a vibe—it’s a set of promises you can state precisely and then check against every situation, including failures.

Safety vs. liveness (with concrete examples)

Safety means “nothing bad ever happens.” Example: in a replicated key-value store, two different values must never be committed for the same log index. Another: a lock service must never grant the same lock to two clients at the same time.

Liveness means “something good eventually happens.” Example: if a majority of replicas are up and the network eventually delivers messages, a write request eventually completes. A lock request eventually gets a yes or a no (not infinite waiting).

Safety is about preventing contradictions; liveness is about avoiding permanent stalls.

Invariants: your non-negotiables

An invariant is a condition that must always hold, in every reachable state. For example:

- “Each log index has at most one committed value.”

- “A leader’s term number never decreases.”

If an invariant can be violated during a crash, timeout, retry, or partition, it wasn’t actually enforced.

What “proof” means here

A proof is an argument that covers all possible executions, not just the “normal path.” You reason about every case: message loss, duplication, reordering; node crashes and restarts; competing leaders; clients retrying.

Specs prevent surprise behavior

A clear spec defines state, allowed actions, and required properties. That prevents ambiguous requirements like “the system should be consistent” from turning into conflicting expectations. Specs force you to say what happens during partitions, what “commit” means, and what clients can rely on—before production teaches you the hard way.

From Theory to Practice: Modeling with TLA+

One of Lamport’s most practical lessons is that you can (and often should) design a distributed protocol at a higher level than code. Before you worry about threads, RPCs, and retry loops, you can write down the rules of the system: what actions are allowed, what state can change, and what must never happen.

What TLA+ is for

TLA+ is a specification language and model-checking toolkit for describing concurrent and distributed systems. You write a simple, math-like model of your system—states and transitions—plus the properties you care about (for example, “at most one leader” or “a committed entry never disappears”).

Then the model checker explores possible interleavings, message delays, and failures to find a counterexample: a concrete sequence of steps that breaks your property. Instead of debating edge cases in meetings, you get an executable argument.

A bug a model can catch

Consider a “commit” step in a replicated log. In code, it’s easy to accidentally allow two different nodes to mark two different entries as committed at the same index under rare timing.

A TLA+ model can reveal a trace like:

- Node A commits entry X at index 10 after hearing from a quorum.

- Node B (with stale data) also forms a quorum and commits entry Y at index 10.

That’s a duplicate commit—a safety violation that might only appear once a month in production, but shows up quickly under exhaustive search. Similar models often catch lost updates, double-applies, or “ack but not durable” situations.

When it’s worth modeling

TLA+ is most valuable for critical coordination logic: leader election, membership changes, consensus-like flows, and any protocol where ordering and failure handling interact. If a bug would corrupt data or require manual recovery, a small model is usually cheaper than debugging it later.

If you’re building internal tooling around these ideas, one practical workflow is to write a lightweight spec (even informal), then implement the system and generate tests from the spec’s invariants. Platforms like Koder.ai can help here by accelerating the build-test loop: you can describe the intended ordering/consensus behavior in plain language, iterate on service scaffolding (React frontends, Go backends with PostgreSQL, or Flutter clients), and keep “what must never happen” visible while you ship.

Practical Takeaways for Building and Operating Reliable Systems

Fund your experiments

Get credits by sharing what you build on Koder.ai or inviting teammates to try it.

Lamport’s big gift to practitioners is a mindset: treat time and ordering as data you model, not assumptions you inherit from the wall clock. That mindset turns into a set of habits you can apply on Monday.

Turn theory into everyday engineering practices

If messages can be delayed, duplicated, or arrive out of order, design each interaction to be safe under those conditions.

- Idempotency by default: make “do it again” harmless. Use idempotency keys for payments, provisioning, or any write you may retry.

- Retries with deduplication: retries are necessary, but without dedup you’ll create double-writes. Track request IDs and store “already processed” markers.

- At-least-once delivery + exactly-once effects: accept that the network may deliver twice; ensure your state changes don’t.

Be careful with timeouts and clocks

Timeouts are not truth; they’re policy. A timeout only tells you “I didn’t hear back in time,” not “the other side didn’t act.” Two concrete implications:

- Don’t treat a timeout as a definitive failure. Design compensations and reconciliation paths.

- Avoid using local clock time to order events across nodes. Use sequence numbers, monotonic counters, or explicit causal metadata (for example, “this update supersedes version X”).

Observability that respects causality

Good debugging tools encode ordering, not just timestamps.

- Trace IDs everywhere: propagate a correlation/trace ID through every hop and log line.

- Causal clues in logs: log message IDs, parent request IDs, and “what I believed the latest version was” when making decisions.

- Deterministic replays: record inputs (commands) so you can replay behavior and confirm whether a bug is timing-dependent or logic-dependent.

Design questions to ask before shipping

Before you add a distributed feature, force clarity with a few questions:

- What happens if the same request is processed twice?

- What ordering do we need (if any), and where is it enforced?

- Which failures are “safe” (no bad state) vs. “loud” (user-visible) vs. “silent” (hidden corruption)?

- What is the recovery path after a partial outage or network split?

- What will we log to reconstruct the happened-before story in production?

These questions don’t require a PhD—just the discipline to treat ordering and correctness as first-class product requirements.

Conclusion and Suggested Next Steps

Lamport’s lasting gift is a way to think clearly when systems don’t share a clock and don’t agree on “what happened” by default. Instead of chasing perfect time, you track causality (what could have influenced what), represent it with logical time (Lamport timestamps), and—when the product requires a single history—build agreement (consensus) so every replica applies the same sequence of decisions.

That thread leads to a practical engineering mindset:

Specify first, then build

Write down the rules you need: what must never happen (safety) and what must eventually happen (liveness). Then implement to that spec, and test the system under delay, partitions, retries, duplicate messages, and node restarts. Many “mystery outages” are really missing statements like “a request may be processed twice” or “leaders can change at any time.”

Learn next, with focused steps

If you want to go deeper without drowning in formalism:

- Read Lamport’s “Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System” to internalize happened-before.

- Skim “Paxos Made Simple” for the safety intuition: once a value is chosen, future progress can’t contradict it.

- Watch a TLA+ intro talk, then model a tiny protocol (a lock service or a two-replica register) and check it.

Try one hands-on exercise

Pick a component you own and write a one-page “failure contract”: what you assume about the network and storage, what operations are idempotent, and what ordering guarantees you provide.

If you want to make this exercise more concrete, build a small “ordering demo” service: a request API that appends commands to a log, a background worker that applies them, plus an admin view showing causality metadata and retries. Doing this on Koder.ai can be a fast way to iterate—especially if you want quick scaffolding, deployment/hosting, snapshots/rollback for experiments, and source-code export once you’re satisfied.

Done well, these ideas reduce outages because fewer behaviors are implicit. They also simplify reasoning: you stop arguing about time and start proving what order, agreement, and correctness actually mean for your system.