Jun 02, 2025·8 min

Mark Russinovich & Windows Internals: Observability & Reliability

Learn how Mark Russinovich’s Windows Internals mindset shaped Sysinternals, WinDbg workflows, and practical observability for debugging and reliability on Windows.

Learn how Mark Russinovich’s Windows Internals mindset shaped Sysinternals, WinDbg workflows, and practical observability for debugging and reliability on Windows.

If you run Windows in production—on laptops, servers, VDI, or cloud VMs—Mark Russinovich’s work still shows up in day-to-day operations. Not because of personality or nostalgia, but because he helped popularize an evidence-first approach to troubleshooting: look at what the OS is actually doing, then explain symptoms with proof.

Observability means you can answer “what is happening right now?” using signals the system produces (events, traces, counters). When a service slows down or logons hang, observability is the difference between guessing and knowing.

Debugging is turning a vague problem (“it froze”) into a specific mechanism (“this thread is blocked on I/O,” “this process is thrashing the page file,” “this DLL injection changed behavior”).

Reliability is the ability to keep working under stress and to recover predictably—fewer incidents, faster restores, and safer changes.

Most “mystery outages” aren’t mysteries—they’re Windows behaviors you haven’t mapped yet: handle leaks, runaway child processes, stuck drivers, DNS timeouts, broken auto-start entries, or security tooling that adds overhead. A basic grasp of Windows internals (processes, threads, handles, services, memory, I/O) helps you recognize patterns quickly and collect the right evidence before the problem disappears.

We’ll focus on practical, operations-friendly workflows using:

The goal isn’t to turn you into a kernel engineer. It’s to make Windows incidents shorter, calmer, and easier to explain—so fixes are safer and repeatable.

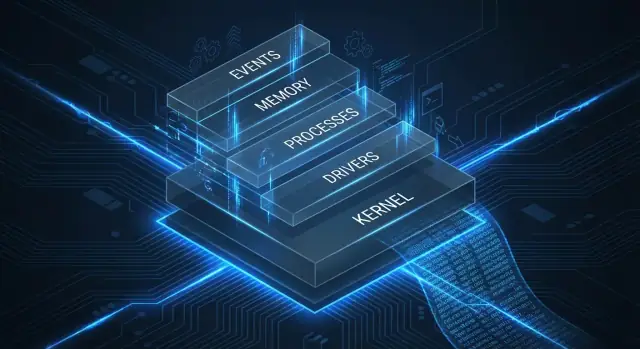

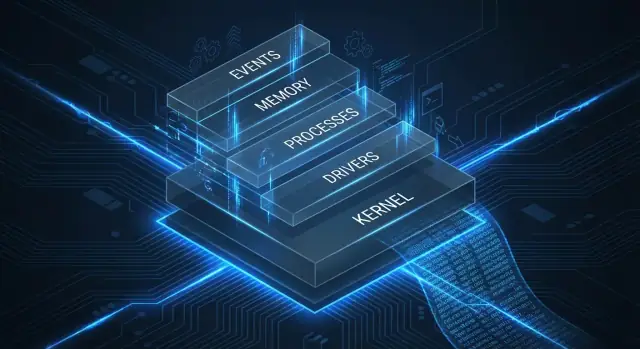

Windows “internals” is simply the set of mechanisms Windows uses to do real work: scheduling threads, managing memory, starting services, loading drivers, handling file and registry activity, and enforcing security boundaries. The practical promise is straightforward: when you understand what the OS is doing, you stop guessing and start explaining.

That matters because most operational symptoms are indirect. “The machine is slow” might be CPU contention, a single hot thread, a driver interrupt storm, paging pressure, or an antivirus filter blocking file I/O. “It hangs” could be a deadlock, a stuck network call, a storage timeout, or a service waiting on a dependency. Boot issues might be a broken autorun entry, a failing driver load, or a policy script that never finishes. Internals knowledge turns vague complaints into testable hypotheses.

At a high level, user mode is where most apps and services run. When they crash, they typically take down only themselves. Kernel mode is where Windows itself and drivers run; problems there can freeze the whole system, trigger a bugcheck (blue screen), or quietly degrade reliability.

You don’t need deep theory to use this distinction—just enough to choose evidence. An app pegging CPU is often user mode; repeated storage resets or network driver issues often point toward kernel mode.

Russinovich’s mindset—reflected in tools like Sysinternals and in Windows Internals—is “evidence first.” Before changing settings, rebooting blindly, or reinstalling, capture what the system is doing: which process, which thread, which handle, which registry key, which network connection, which driver, which event.

Once you can answer “what is Windows doing right now, and why,” fixes become smaller, safer, and easier to justify—and reliability work stops being reactive firefighting.

Sysinternals is best understood as a “visibility toolkit” for Windows: small, portable utilities that reveal what the system is actually doing—process by process, handle by handle, registry key by registry key. Instead of treating Windows as a black box, Sysinternals lets you observe the behavior behind symptoms like “the app is slow,” “CPU is high,” or “the server keeps dropping connections.”

A lot of operational pain comes from reasonable-sounding guesses: it must be DNS, it’s probably antivirus, Windows Update is stuck again. The Sysinternals mindset is simple: trust your instincts enough to form a hypothesis, then verify it with evidence.

When you can see which process is consuming CPU, which thread is waiting, which file path is being hammered, or which registry value keeps getting rewritten, you stop debating opinions and start narrowing causes. That shift—from narrative to measurement—is what makes internals knowledge practical, not academic.

These tools are built for the “everything is on fire” moment:

That matters when you can’t afford a long setup cycle, a heavy agent rollout, or a reboot just to collect better data.

Sysinternals is powerful, and power deserves guardrails:

Used this way, Sysinternals becomes a disciplined method: observe the invisible, measure the truth, and make changes that are justified—not hopeful.

If you only keep two Sysinternals tools in your admin toolkit, make it Process Explorer and Process Monitor. Together they answer the most common “what is Windows doing right now?” questions without requiring an agent, a reboot, or a heavy setup.

Process Explorer is Task Manager with x-ray vision. When a machine is slow or unstable, it helps you pinpoint which process is responsible and what it’s tied to.

It’s especially useful for:

That last point is a reliability superpower: “Why can’t I delete this file?” often becomes “This service has an open handle to it.”

Process Monitor (Procmon) captures detailed events across file system, registry, and process/thread activity. It’s the tool for questions like: “What changed when the app hung?” or “What is hammering the disk every 10 minutes?”

Before you hit Capture, frame the question:

Procmon can overwhelm you unless you filter aggressively. Start with:

Common outcomes are very practical: identifying a misbehaving service repeatedly querying a missing registry key, spotting a runaway “real-time” file scan touching thousands of files, or finding a missing DLL load attempt (“NAME NOT FOUND”) that explains why an app won’t start on one machine but works on another.

When a Windows machine “feels off,” you often don’t need a full monitoring stack to get traction. A small set of Sysinternals tools can quickly answer three practical questions: What starts automatically? What is talking on the network? Where did the memory go?

Autoruns is the fastest way to understand everything that can launch without a user explicitly running it: services, scheduled tasks, shell extensions, drivers, and more.

Why it matters for reliability: startup items are frequent sources of slow boots, intermittent hangs, and CPU spikes that only appear after login. One unstable updater, legacy driver helper, or broken shell extension can degrade the whole system.

Practical tip: focus on entries that are unsigned, recently added, or failing to load. If disabling an item stabilizes the box, you’ve turned a vague symptom into a specific component you can update, remove, or replace.

TCPView gives you an instant map of active connections and listeners, tied to process names and PIDs. It’s ideal for quick sanity checks:

Even for non-security investigations, this can uncover runaway agents, misconfigured proxies, or “retry storms” where the app looks slow but the root cause is network behavior.

RAMMap helps you interpret memory pressure by showing where RAM is actually allocated.

A useful baseline distinction:

If users report “low memory” while Task Manager looks confusing, RAMMap can confirm whether you have true process growth, heavy file cache, or something like a driver consuming nonpaged memory.

If an app slows down over days, Handle can reveal handle counts growing without bound (a classic leak pattern). VMMap helps when memory usage is odd—fragmentation, large reserved regions, or allocations that don’t show up as simple “private bytes.”

Windows operations often starts with what’s easiest to grab: Event Viewer and a few screenshots of Task Manager. That’s fine for breadcrumbs, but reliable incident response needs three complementary signal types: logs (what happened), metrics (how bad it got), and traces (what the system was doing moment-to-moment).

Windows event logs are excellent for identity, service lifecycle, policy changes, and app-level errors. They’re also uneven: some components log richly, others log sparsely, and message text can be vague (“The application stopped responding”). Treat them as a timeline anchor, not the whole story.

Common wins:

Performance counters (and similar sources) answer, “Is the machine healthy?” During an outage, start with:

Metrics won’t tell you why a spike happened, but they’ll tell you when it started and whether it’s improving.

Event Tracing for Windows (ETW) is Windows’ built-in flight recorder. Instead of ad-hoc text messages, ETW emits structured events from the kernel, drivers, and services at high volume—process/thread activity, file I/O, registry access, TCP/IP, scheduling, and more. This is the level where many “mystery stalls” become explainable.

A practical rule:

Avoid “turn on everything forever.” Keep a small always-on baseline (key logs + core metrics) and use short, targeted ETW captures during incidents.

The fastest diagnoses come from aligning three clocks: user reports (“10:42 it froze”), metric inflections (CPU/disk spike), and log/ETW events at the same timestamp. Once your data shares a consistent time base, outages stop being guesses and start becoming narratives you can verify.

Windows’ default event logs are useful, but they often miss the “why now?” details operators need when something changes unexpectedly. Sysmon (System Monitor) fills that gap by recording higher-fidelity process and system activity—especially around launches, persistence, and driver behavior.

Sysmon’s strength is context. Instead of just “a service started,” you can often see which process started it, with full command line, parent process, hashes, user account, and clean timestamps for correlation.

That’s valuable for reliability work because many incidents begin as “small” changes: a new scheduled task, a silent updater, a stray script, or a driver that behaves badly.

A “log everything” Sysmon config is rarely a good first move. Start with a minimal, reliability-focused set and expand only when you have clear questions.

Good early candidates:

Tune with targeted include rules (critical paths, known service accounts, key servers) and carefully chosen exclude rules (noisy updaters, trusted management agents) so the signal stays readable.

Sysmon often helps confirm or rule out common “mystery change” scenarios:

Test impact on representative machines first. Sysmon can increase disk I/O and event volume, and centralized collection can get expensive quickly.

Also treat fields like command lines, usernames, and paths as sensitive. Apply access controls, retention limits, and filtering before broad rollout.

Sysmon is best as high-value breadcrumbs. Use it alongside ETW for deep performance questions, metrics for trend detection, and disciplined incident notes so you can connect what changed to what broke—and how you fixed it.

When something “just crashes,” the most valuable artifact is often a dump file: a snapshot of memory plus enough execution state to reconstruct what the process (or the OS) was doing at the moment of failure. Unlike logs, dumps don’t require you to predict the right message ahead of time—they capture the evidence after the fact.

Dumps can point to a specific module, call path, and failure type (access violation, heap corruption, deadlock, driver fault), which is hard to infer from symptoms alone.

WinDbg turns a dump into a story. The essentials:

A typical workflow is: open the dump → load symbols → run an automated analysis → validate by checking top stacks and involved modules.

“It’s frozen” is a symptom, not a diagnosis. For hangs, capture a dump while the app is unresponsive and inspect:

You can often self-diagnose clear-cut issues (repeatable crashes in one module, obvious deadlocks, strong correlation to a specific DLL/driver). Escalate when dumps implicate third-party drivers/security software, kernel components, or when symbols/source access is missing—then a vendor (or Microsoft) may be needed to interpret the full chain.

A lot of “mysterious Windows issues” repeat the same patterns. The difference between guessing and fixing is understanding what the OS is doing—and the Internals/Sysinternals mental model helps you see it.

When people say “the app is leaking memory,” they often mean one of two things.

Working set is the physical RAM currently backing the process. It can go up and down as Windows trims memory under pressure.

Commit is the amount of virtual memory the system has promised to back with either RAM or the page file. If commit keeps climbing, you have a real leak risk: eventually you hit the commit limit and allocations start failing or the host becomes unstable.

A common symptom: Task Manager shows “available RAM,” but the machine still slows down—because commit, not free RAM, is the constraint.

A handle is a reference to an OS object (file, registry key, event, section, etc.). If a service leaks handles, it may run fine for hours or days, then start failing with odd errors (can’t open files, can’t create threads, can’t accept connections) as per-process handle counts grow.

In Process Explorer, watch handle count trends over time. A steady upward slope is a strong clue the service is “forgetting to close” something.

Storage problems don’t always show as high throughput; they often show as high latency and retries. In Process Monitor, look for:

Also pay attention to filter drivers (AV, backup, DLP). They can insert themselves into the file I/O path and add delay or failures without the application “doing anything wrong.”

A single hot process is straightforward: one executable burns CPU.

System-wide contention is trickier: CPU is high because many threads are runnable and fighting over locks, disk, or memory. Internals thinking pushes you to ask: “Is the CPU doing useful work, or spinning while blocked elsewhere?”

When timeouts happen, map process → connection using TCPView or Process Explorer. If the wrong process owns the socket, you’ve found a concrete culprit. If the right one owns it, look for patterns: SYN retries, long-established connections stuck idle, or an explosion of short-lived outbound attempts suggesting DNS/firewall/proxy trouble rather than “the app is down.”

Reliability work gets easier when every incident follows the same path. The goal isn’t to “run more tools”—it’s to make better decisions with consistent evidence.

Write down what “bad” looks like in one sentence: “App freezes for 30–60 seconds when saving a large file” or “CPU spikes to 100% every 10 minutes.” If you can reproduce, do it on demand; if you can’t, define the trigger (time window, workload, user action).

Before collecting heavy data, confirm the symptom and scope:

This is where quick checks (Task Manager, Process Explorer, basic counters) help you choose what to capture next.

Capture evidence like you’re handing it to a teammate who wasn’t there. A good case file usually includes:

Keep captures short and targeted. A 60-second trace that covers the failure window beats a 6-hour capture nobody can open.

Translate what you collected into a plain narrative:

If you can’t explain it simply, you probably need a cleaner capture or a narrower hypothesis.

Apply the smallest safe fix, then confirm with the same reproduction steps and a “before vs. after” capture.

To reduce MTTR, standardize playbooks and automate the boring parts:

After resolution, ask: “What signal would have made this obvious earlier?” Add that signal—Sysmon event, ETW provider, a performance counter, or a lightweight health check—so the next incident is shorter and calmer.

The point of Windows internals work isn’t to “win” a debugging session—it’s to turn what you saw into changes that keep the incident from returning.

Internals tools usually narrow a problem to a small set of levers. Keep the translation explicit:

Write down the “because”: “We changed X because we observed Y in Process Monitor / ETW / dumps.” That sentence prevents tribal knowledge from drifting.

Make your change process match the blast radius:

Even when the root cause is specific, durability often comes from reusable patterns:

Keep what you need, and protect what you shouldn’t collect.

Limit Procmon filters to suspected processes, scrub paths/usernames when sharing, set retention for ETW/Sysmon data, and avoid payload-heavy network capture unless necessary.

Once you have a repeatable workflow, the next step is to package it so others can run it consistently. This is where a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can be useful: you can turn your incident checklist into a small internal web app (React UI, Go backend with PostgreSQL) that guides responders through “observe → capture → explain,” stores timestamps and artifacts, and standardizes naming and case-file structure.

Because Koder.ai builds apps through chat using an agent-based architecture, teams can iterate quickly—adding a “start ETW session” button, a Procmon filter template library, snapshot/rollback of changes, or an exportable runbook generator—without rebuilding everything in a traditional dev pipeline. If you’re sharing internal reliability practices, Koder.ai also supports source-code export and multiple tiers (free through enterprise), so you can start small and scale governance later.

Once a week, pick one tool and a 15-minute exercise: trace a slow app start with Procmon, inspect a service tree in Process Explorer, review Sysmon event volume, or take one crash dump and identify the failing module. Small reps build the muscle memory that makes real incidents faster—and safer.

Mark Russinovich popularized an evidence-first approach to Windows troubleshooting and shipped (and influenced) tools that make the OS observable in practice.

Even if you never read Windows Internals, you’re likely relying on workflows shaped by Sysinternals, ETW, and dump analysis to shorten incidents and make fixes repeatable.

Observability is your ability to answer “what is happening right now?” from system signals.

On Windows, that typically means combining:

Internals knowledge helps you turn vague symptoms into testable hypotheses.

For example, “the server is slow” becomes a smaller set of mechanisms to validate: CPU contention vs paging pressure vs I/O latency vs driver/filter overhead. That speeds triage and helps you capture the right evidence before the problem disappears.

Use Process Explorer to identify who is responsible.

It’s best for fast answers like:

Use Process Monitor when you need the activity trail across file, registry, and process/thread operations.

Practical examples:

Filter aggressively and capture only the failure window.

A good starting workflow:

A smaller trace you can analyze beats a massive capture nobody can open.

Autoruns answers “what starts automatically?”—services, scheduled tasks, drivers, shell extensions, and more.

It’s especially useful for:

Focus first on entries that are unsigned, , or , and disable items one at a time with notes.

ETW (Event Tracing for Windows) is Windows’ built-in high-volume, structured “flight recorder.”

Use ETW when logs and metrics tell you that something is wrong, but not why—for example, stalls caused by I/O latency, scheduling delays, driver behavior, or dependency timeouts. Keep captures short, targeted, and time-correlated with the reported symptom.

Sysmon adds high-context telemetry (parent/child process, command lines, hashes, driver loads) that helps you answer “what changed?”

For reliability, it’s useful to confirm:

Start with a minimal config and tune includes/excludes to control event volume and cost.

A dump is often the most valuable artifact for crashes and hangs because it captures execution state after the fact.

WinDbg turns dumps into answers, but correct symbols are essential for meaningful stacks and module identification.