Apr 26, 2025·8 min

Michael Dell’s Playbook: Supply Chain Discipline and B2B Focus

A practical look at how Dell scaled through direct sales, tight inventory control, and B2B priorities—and what operators can copy without hype.

A practical look at how Dell scaled through direct sales, tight inventory control, and B2B priorities—and what operators can copy without hype.

Studying Michael Dell isn’t about hero worship. Dell’s early success is better understood as a series of operating choices—many of them unglamorous—that stacked the odds in his favor. The story matters because it turns strategy into mechanics: what to build, when to buy, how to price, how to ship, and how to keep cash from getting trapped in the wrong places.

For founders and operators, Dell is a uniquely useful case because the company won in a market that looked commoditized and brutally competitive. PCs were not rare, magical products; they were interchangeable boxes of parts. That’s exactly why the playbook is worth revisiting: it shows how operational excellence can create durable advantage even when the product itself isn’t proprietary.

This article frames the Dell playbook around two pillars that reinforce each other:

Together, these choices improved working capital, reduced risk, and made Dell easier to run at scale.

You’ll learn how Dell’s direct sales model changed the flow of information (orders first, production second), why inventory turns can matter more than big revenue numbers, and how supplier relationships become leverage when your operations are predictable.

Most importantly, each section is written to be “copy-and-adapt.” You’ll be able to translate the ideas into practical questions for your own business: Where is cash getting stuck? What decisions should be standardized? Which customers value reliability enough to pay for it? And what metrics would tell you the model is actually working?

Michael Dell’s story is useful because it’s not mainly about inventing new technology—it’s about designing a system that moved faster than competitors and turned operating choices into durable advantage.

Dell started in 1984 by assembling PCs to order while at the University of Texas. Through the late 1980s and early 1990s, the company expanded nationally and then internationally, leaning heavily on selling directly to customers rather than through retail shelves.

By the mid-to-late 1990s, Dell had proven it could scale this approach: high volumes, tight control of costs, and increasingly sophisticated logistics. In the 2000s, the center of gravity shifted toward business and enterprise buyers—customers who cared less about the cheapest headline price and more about consistency, service, and predictable fleet management.

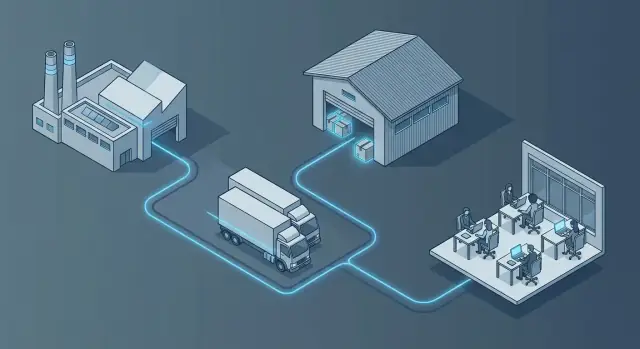

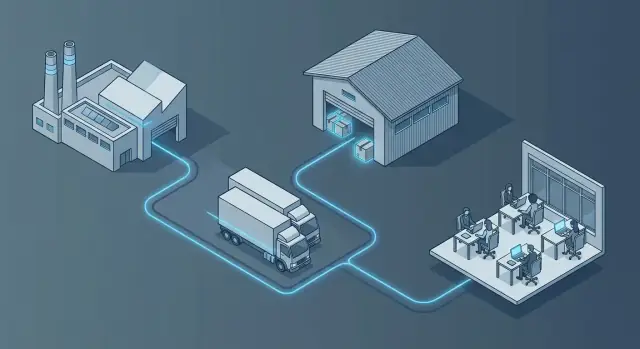

The direct model meant customers told Dell what they wanted first, and Dell built it after the order—then shipped it straight to them.

That sounds simple, but it changed everything:

Two major pivots defined the big moves. First, Dell industrialized build-to-order so it worked not just for enthusiasts, but at mass scale. Second, as consumer PC competition intensified and product differences narrowed, Dell leaned harder into B2B: standardized configurations, procurement-friendly processes, and support that matched how IT departments actually operate.

This approach wasn’t magic. PC demand cycles, component shortages, and shifts in how people buy computers (including stronger retail and later online competitors) reduced the uniqueness of “direct.” The enduring lesson is that the system must evolve: what starts as differentiation can become table stakes, and discipline has to keep finding new places to matter.

Dell’s early advantage wasn’t a magical component or a secret factory trick—it was a selling method that reshaped everything downstream. By selling direct to customers rather than fighting for space on retail shelves, Dell turned “what to build” from a guess into a response.

Traditional PC makers pushed boxes into stores and hoped they sold. Dell went the other way: take the order first, then fulfill it. That direct relationship created two valuable assets at once—customer data and pricing control.

Without a retailer in the middle, Dell could see what people actually wanted (and what they stopped wanting) in near real time. It also meant fewer markups and fewer incentives to “stuff the channel” with inventory just to hit quarterly numbers.

The build-to-order core is simple: only assemble after demand is known. Instead of producing thousands of identical machines and discounting the leftovers later, Dell could configure systems based on current orders.

This approach reduces the risk of building the wrong mix—especially important in the PC market, where parts and specs age quickly. It also supports wider choice: customers can pick from standardized options, while the factory stays focused on repeatable assembly.

Direct orders don’t just trigger assembly—they guide what Dell needs to keep on hand and how fast it must move. If a certain processor or hard drive starts showing up in a growing share of orders, procurement can respond immediately.

That tight loop is the point: orders inform what to stock, what to prioritize in shipping, and where service teams should prepare for likely support needs. The sales model becomes an operational radar.

The downside is obvious: fewer customers casually discover your product on a store shelf. Direct selling requires stronger marketing, clearer configuration choices, and a buying experience customers trust.

It also shifts responsibility onto the company. When you own the relationship, you own the expectations—accurate delivery dates, reliable logistics, straightforward returns, and responsive support. Dell’s direct model wasn’t just a sales tactic; it was a promise operations had to keep.

Dell’s insight wasn’t that forecasting is useless—it’s that in fast-moving hardware, being fast often beats being right. When CPUs, drives, and memory drop in price every few weeks, inventory isn’t an asset; it’s a risk sitting on a shelf.

Holding weeks of parts means you can be stuck with yesterday’s components (and yesterday’s cost) while competitors ship newer specs for less. Even if you can sell the old stock, you may have to discount it, shrinking margins. Low inventory also lowers the chance of being caught with the wrong mix—too many of one model, not enough of another—when customer preferences shift.

Working capital is the money tied up to keep the business running day to day. If you buy a large pile of components in advance, cash leaves your account and sits in boxes until those PCs are sold.

Dell pushed the opposite: get the order, then pull parts through the system. The practical benefit is simple:

In operations terms, inventory isn’t just stock—it’s time and cash frozen in place.

Low inventory only works if suppliers aren’t treated like distant vendors. They’re part of the daily rhythm. That means constant sharing of demand signals, quick confirmation of availability, and clear rules for substitutions when a part goes short.

Instead of betting on a quarterly forecast, the system relies on frequent updates: what’s selling today, what’s arriving tomorrow, and what must be expedited now.

There’s a limit. If you squeeze buffers to the point where one late truck stops shipments, you don’t have lean operations—you have missed deliveries.

Common pitfalls include:

The goal is controlled inventory: small where it’s safe, and intentional where reliability matters.

Dell’s surprising advantage wasn’t exotic technology—it was restraint. By limiting the number of components it allowed into the system, Dell reduced complexity everywhere: purchasing, assembly, testing, support, and returns. Standardization became a scale engine.

When you buy fewer distinct parts, you spend less time sourcing, qualifying, and planning around them. On the factory floor, common components mean simpler work instructions, fewer assembly errors, and faster training. The build process becomes repeatable, which is exactly what you want when demand spikes.

High-volume orders on a small set of CPUs, drives, memory modules, and motherboards increase negotiation leverage with suppliers. It also makes substitutions easier when shortages hit: if multiple models share the same parts, you can reroute inventory to whatever configurations are selling without rewriting the entire bill of materials.

Every new part is another potential failure mode. Fewer variants mean fewer combinations to test and fewer compatibility issues to debug. That tightens quality control and lowers the cost of support—especially important as Dell moved into enterprise accounts that expect predictable uptime.

Standardization doesn’t mean one size fits all. Dell paired a controlled set of approved parts with a configuration menu customers could understand: memory, storage, warranty, peripherals. The trick is to standardize behind the curtain while keeping the buying experience flexible.

A useful rule: if a component doesn’t clearly improve customer value or margins, it’s a candidate for removal.

Dell’s supply chain advantage wasn’t only about squeezing suppliers on price. It was about building a system where suppliers wanted to line up behind Dell—because the economics worked for them.

When a company can turn orders into cash quickly, it can offer something many buyers can’t: steadier, more predictable pull-through. Suppliers benefit when volume is consistent and schedules are reliable.

For Dell, leverage came from being a high-throughput channel for components. For suppliers, the prize was scale and a clearer view of demand. That alignment matters more than a one-time discount, because it reduces suppliers’ risk and waste.

The direct model generated clean order signals: what customers actually bought, in real time. Sharing those signals—forecasts, order patterns, and delivery cadence—helps suppliers plan production and logistics with fewer surprises.

In practice, this is what turns negotiation into coordination. Pricing improves, but so do lead times, quality, and responsiveness.

A key idea is pushing inventory closer to the assembly point without Dell owning it for long. Techniques like vendor-managed inventory and nearby supplier hubs shorten replenishment cycles and reduce stockouts.

This setup can:

Strong partnerships can become a single point of failure if you over-depend on one supplier, one geography, or one specialized part. The best operators balance collaboration with contingency: second sources where feasible, clear escalation paths, and periodic stress tests.

Dell’s real leverage wasn’t just bargaining power—it was running an operating model that made suppliers faster, more certain, and more profitable when they stayed close.

Dell didn’t start by chasing the largest enterprises. The early wins came from small businesses that wanted decent performance, a fair price, and someone who would actually pick up the phone. Over time, that customer base became a bridge to bigger accounts—because the same traits that matter to a 50-person company also matter to a 50,000-person one, just with more paperwork.

As Dell moved from small business into enterprise customers, the pitch changed from “best specs for the money” to “lower total cost and fewer surprises.” Enterprises aren’t only buying a device; they’re buying predictability: standard images, consistent parts, clear warranties, and a vendor that won’t disappear mid-contract.

Procurement teams and IT departments value vendors that make buying and maintaining fleets boring—in a good way. What tends to matter most:

B2B is slower. Security reviews, pilot programs, vendor onboarding, and contract negotiations stretch timelines. But once you win, you often get multi-year refresh cycles, larger order sizes, and expansion into adjacent teams or geographies.

Services turn a hardware sale into an ongoing relationship. Deployment help, managed support, and warranty programs reduce downtime and workload for IT. That operational relief is sticky—and it helps defend accounts even when competitors match on price.

Dell’s B2B edge wasn’t only about cheaper PCs—it was about reducing the daily friction inside IT departments. Enterprise buyers care less about a single great spec and more about whether 5,000 machines can be rolled out, supported, and refreshed without chaos.

IT teams want predictable fleets: a few approved models, consistent drivers, and one golden image they can deploy at scale. Standardization reduces help-desk tickets and speeds onboarding.

Dell’s operational promise to IT buyers is simple: pick a standard set, keep it stable, and make replacements match. When a laptop dies, the goal isn’t a fancy upgrade—it’s getting an employee back to work with minimal reconfiguration.

Strong customer operations treat hardware as a lifecycle, not a one-time sale:

This is where reliability and total cost become tangible: fewer interruptions, fewer one-off exceptions, and fewer urgent escalations.

Services matter, but only when they’re concrete. Instead of vague “white-glove” claims, successful bundles are specific: next-business-day parts, onsite repair, pre-imaging, device tracking, or a managed refresh program. If you can’t define what happens, when, and who owns it, don’t sell it.

Operational excellence shows up in boring metrics:

When customer operations are strong, IT departments stop shopping model-by-model—and start standardizing around you.

Dell’s advantage wasn’t just a clever direct sales model—it was the measurement system underneath it. When you build to order and keep inventory lean, small delays and quality slips show up fast. Metrics turned weak signals into actions.

Speed was a competitive feature, so Dell tracked time like a production company, not a “PC brand.” The most useful cycle-time measures were end-to-end, not departmental:

The key was treating these as one connected timer. If shipping slowed, sales promises had to adjust—or operations had to escalate fixes immediately.

Build-to-order only works if what ships works the first time. Otherwise, you trade inventory cost for support cost and reputation damage. Dell monitored:

This made quality a feedback loop, not a post-mortem.

Operational excellence shows up in cash. Dell kept close watch on:

Shortening the cash cycle funded growth without needing as much external capital.

Metrics only matter if they create habits. Dell-style operating cadences typically included weekly reviews for cycle time and quality, plus monthly deep dives on inventory turns and cash conversion. Targets were simple, visible, and owned—so when a number slipped, everyone knew who was leading the fix and by when.

Dell’s advantages weren’t permanent secrets. Once rivals understood what was happening—sell direct, build to order, keep inventory low—they copied parts of the model. The difference was execution speed and organizational focus. Many competitors still had to protect retail channels, manage bigger finished-goods buffers, or rely on slower planning cycles. Copying the “what” was easier than copying the “how.”

As PCs became more interchangeable, commoditization turned operational excellence into table stakes rather than a differentiator. If two vendors can both deliver quickly with acceptable quality, buyers treat the hardware like a component in a broader IT budget. That intensifies price competition and forces differentiation elsewhere—support, financing, deployment services, security tooling, or standardized enterprise configurations.

Dell’s demand-first approach works best when supply is flexible and component lead times are manageable. It strains in the opposite conditions:

In these moments, low inventory stops looking like discipline and starts looking like fragility. The response often requires selective buffering, stronger supply commitments, or designing products around interchangeable components.

Not every business benefits from direct, build-to-order operations. It’s a weaker fit when:

The broader lesson: the playbook is powerful, but it’s conditional. It rewards clarity about where speed and working capital truly create an edge—and where the market forces you to compete on something else.

Dell’s story isn’t just “move fast” or “optimize inventory.” It’s a reminder that operations are a strategy—especially when you’re selling something physical, time-sensitive, or service-heavy. The takeaway is to earn complexity gradually, and only when the business has the demand and systems to support it.

Many early teams try to look enterprise-ready by adding warehouses, too many shipping options, multiple contract manufacturers, and custom configurations for every customer. That complexity is expensive, distracting, and hard to unwind.

Start with the simplest supply chain that can reliably deliver. Add steps only when they clearly unlock growth (shorter lead times, lower unit cost, higher conversion) and when you have the volume to justify them.

A core Dell idea was aligning build decisions with real demand. You may not be building PCs, but the principle transfers.

If you can, pull demand forward with:

These mechanisms do two things: they reduce the risk of building the wrong thing, and they reduce working capital pressure by bringing cash closer to the moment you spend it.

Choice can quietly become chaos. Every variation creates forecasting issues, support burden, more edge cases, and more supplier dependencies.

Instead, design a small number of standard packages and use constrained options (for example: good/better/best tiers, a limited set of add-ons). Customers still get flexibility, but you keep the operational load manageable.

It’s tempting to source everything from everywhere “just in case.” Dell’s playbook suggests the opposite: concentrate spend with a smaller set of reliable suppliers, collaborate closely, and use performance data to improve terms over time.

A practical operating rhythm:

A supply chain isn’t a trophy. It’s a system that should get simpler as you scale, not more fragile.

A Dell-style model depends on tight feedback loops—order signals, inventory positions, supplier lead times, and cycle-time metrics—surfacing quickly enough to change decisions.

If you’re building internal tools (quote-to-cash, inventory views, SLA tracking, exception workflows), platforms like Koder.ai can help teams create web apps and dashboards from a chat interface, then iterate as processes change. The key is the same Dell lesson: shorten the cycle from “we noticed a problem” to “we changed the operating system.”

Dell’s advantage wasn’t a single trick—it was operational clarity: a system where sales, forecasting, procurement, and support reinforced each other. Use this as a “copy the principles, adapt the implementation” checklist.

Operational clarity—knowing exactly how you make, sell, deliver, and support—can outlast product cycles. Copy the discipline, adapt the mechanics, and make execution your moat.

It’s a concrete example of how operational choices (selling, building, sourcing, and measuring) can create advantage even when the product looks like a commodity. The value is in the mechanics: how to reduce risk, keep cash moving, and scale a repeatable system.

The two pillars are:

Together they improve working capital, reduce operational risk, and make scaling easier.

In the direct model, the order comes first, and production follows. That shifts you from forecasting what might sell to responding to what actually sold.

Practically, it:

Low inventory matters because component prices and customer preferences can change quickly. Inventory isn’t just “stock”—it’s cash and time frozen in place.

Keeping inventory tight helps:

It only works if suppliers operate as part of your daily system—not distant vendors.

Useful practices include:

If you cut buffers too hard, you can create fragility where one late shipment stops everything.

Common mistakes:

The goal is controlled inventory, not zero inventory.

Standardization reduces complexity across purchasing, assembly, testing, support, and returns. Fewer variants means:

You can still offer choice by keeping a constrained configuration menu while standardizing “behind the curtain.”

B2B buyers purchase predictability more than specs. They often care most about:

That’s why total cost and fewer surprises can beat the lowest sticker price.

Operational excellence becomes real when it shows up in measurable performance. Practical metrics from the post include:

Use simple targets and regular review cadences so numbers drive actions, not dashboards.

It’s a weaker fit when your market requires instant retail availability, hands-on discovery, heavy channel partners, or when demand is dominated by a few lumpy deals.

It also strains during:

In those cases you may need selective buffering, hybrid channels, or redesigned offerings to keep reliability high.