Oct 12, 2025·7 min

Multi-region hosting for data residency: regions, latency, docs

Learn multi-region hosting for data residency: how to pick cloud regions, manage latency, and document data flows for audits and customer reviews.

Why multi-region matters for data residency

Data residency questions usually start with a simple customer ask: “Can you keep our data in our country?” The hard part is that their users, admins, and support teams may be global. Multi-region hosting is how you meet local storage needs without blocking day-to-day work.

This choice affects three practical decisions:

- Where data is stored (databases, file uploads, logs, backups)

- Where data is processed (app servers, background jobs, analytics, AI features)

- Who can access it (your staff, contractors, cloud operators) and from where

If any of those happen outside the agreed region, you may still have a cross-border transfer even if the main database stays “local.”

The tradeoffs to expect

Multi-region setups help with compliance, but they are not free. You trade simplicity for control. Costs rise (more infrastructure and monitoring). Complexity rises too (replication, failover, region-specific configuration). Performance can also take a hit, because you may need to keep requests and processing inside a region instead of using the closest server worldwide.

A common example: an EU customer wants EU-only storage, but half their workforce is in the US. If US-based admins log in and run exports, that creates access and transfer questions. A clean setup spells out what stays in the EU, what can be accessed remotely, and what safeguards apply.

Typical triggers that force the conversation

Most teams revisit hosting regions when one of these hits:

- Enterprise procurement asks for a residency commitment in contracts and security reviews

- Regulated industries (health, finance, education) require stricter controls and audit trails

- Public sector workloads require in-country hosting or specific approved locations

- Cross-border rules and internal policies limit where personal or sensitive data can be stored or processed

Key terms: residency, transfers, access, and processing

Data residency is where your data is stored when it is “at rest.” Think database files, object storage, and backups sitting on disks in a specific country or cloud region.

People often mix residency with data access and data transfer. Access is about who can read or change the data (for example, a support engineer in another country). Transfer is about where data travels (for example, an API call crossing borders). You can meet residency rules while still violating transfer rules if data is routinely sent to another region for analytics, monitoring, or support.

Processing is what you do with the data: storing it, indexing it, searching it, training on it, or generating reports. Processing can happen in a different place than storage, so compliance teams usually ask for both.

To make these discussions concrete, group your data into a few everyday buckets: customer content (files, messages, uploads), account and billing data, metadata (IDs, timestamps, config), operational data (logs and security events), and recovery data (backups and replicas).

During reviews, you will almost always be asked two things: where each bucket is stored, and where it might go. Customers may also ask how human access is controlled.

A practical example: your main database is in Germany (storage), but your error tracking is in the US (transfer). Even if customer content never leaves Germany, logs might include user IDs or request payload snippets that do. That’s why logs and analytics deserve their own line in your documentation.

When you document this, aim to answer:

- Where is the primary storage and where are backups kept?

- What services receive copies (CDN, analytics, monitoring, email)?

- Who can access data, from where, and under what approval?

- What processing happens outside the residency region, if any?

- What is the retention period for each data type?

Clear terms up front save time later, especially when customers want a simple, confident explanation.

Start with a simple inventory of data and systems

Before you pick regions, write down what data you have and where it touches your stack. This sounds basic, but it’s the fastest way to avoid “we thought it stayed in-region” surprises.

Start with data types, not laws. Most products handle a mix: customer account details (PII), payment records (often tokenized but still sensitive), support conversations, and product telemetry like logs and events. Include derived data too, like reports, analytics tables, and AI-generated summaries.

Next, list every system that can see or store that data. That usually includes app servers, databases, object storage for uploads, email and SMS providers, error monitoring, customer support tools, and CI/CD or admin consoles. If you use snapshots, backups, or exports, treat those as separate data stores.

Capture the lifecycle in plain language: how data is collected, where it is stored, what processing happens (search, billing, moderation), who it is shared with (vendors, internal teams), how long it is kept, and how deletion actually works (including backups).

Keep the inventory usable. A small checklist is often enough: data type, system, region (storage and processing), what triggers movement (user action, background job, support request), and retention.

Map your data flows before choosing regions

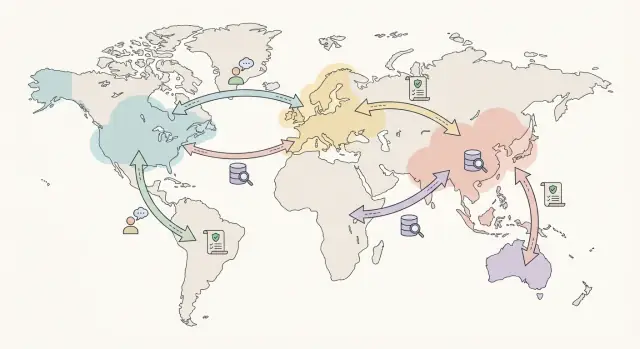

Before you pick locations, you need a simple picture of where data actually goes. Region planning can fail on paperwork alone if you can’t explain the path of personal data to a customer or auditor.

Start with a plain-language diagram. One page is enough. Write it like a story: a user signs in, uses the app, data is stored, and supporting systems record what happened. Then label each step with two things: where it runs (region or country), and whether the data is at rest (stored) or in transit (moving).

Don’t stop at the happy path. The flows that surprise people are operational ones: a support engineer opening a ticket with a screenshot, an incident response session with temporary access, a database restore from backups, or an export for a customer.

A quick way to keep the map honest is to cover:

- App traffic and what gets logged

- Primary storage plus backups and snapshots

- Observability (logs, traces, error reports) and retention

- Human access (support, admin tools, incident response) and approvals

- Data movement (exports, imports, restores, replication)

Add third parties, even if they seem minor. Payments, email delivery, analytics, and customer support tools often process identifiers. Note what data they receive, where they process it, and whether you can choose their region.

Once the map is clear, region selection becomes matching, not guesswork.

How to choose regions that fit residency requirements

Pilot multi-region faster

Spin up a pilot app and test region choices without a big upfront build.

Start with the rule, not the cloud map. Ask what your customers or regulators actually require: which country (or set of countries) must the data stay in, which locations are explicitly not allowed, and whether there are narrow exceptions (for example, support access from another country).

A key decision is how strict the boundary is. Some programs mean single-country only: storage, backups, and admin access kept inside one country. Others allow a broader area (for example, a defined economic zone) as long as you can show where data is stored and who can access it.

A practical checklist

Before you commit, validate each candidate region against real constraints:

- Residency fit: is the region inside the allowed geography, and are any dependencies outside it (monitoring, logging, email, analytics)?

- Service fit: are the managed services you need available there (database, object storage, load balancers, key management, private networking)?

- Data controls: can you keep encryption keys in-region, limit admin access, and prove where backups and snapshots live?

- Resilience plan: can you fail over without leaving the allowed boundary?

- Operational reality: can your team operate it without “everyone needs production access from anywhere” becoming the norm?

Proximity still matters, but it comes second. Choose the closest compliant region to your users for performance. Then handle operations with process and access controls (role-based access, approvals, break-glass accounts) rather than by moving data to wherever it’s easiest to manage.

Finally, write down the decision: the allowed boundary, selected regions, failover plan, and what data is permitted to leave (if any). That single page saves hours in questionnaires.

Keep latency reasonable without breaking residency

Latency is mostly about physics and about how many times you ask for data. Distance matters, but so do extra database round trips, network routing, and slow starts when services scale.

Start by measuring before you change anything. Pick 3 to 5 key user actions (login, load dashboard, create an order, search, export report). Track p50 and p95 from the geographies that matter to you. Keep those numbers somewhere you can compare across releases.

A simple rule: keep protected data and the paths that touch it local, then make everything else global-friendly. The biggest performance wins usually come from cutting cross-region chatter.

Keep read and write paths local

If a user in Germany has data that must stay in the EU, aim to keep the app server, primary database, and background jobs for that tenant in the EU. Avoid bouncing auth and session checks to another region on every request. Reduce chatty APIs by making fewer database calls per page.

Caching helps, but be careful where it lives. Cache public or non-sensitive content globally. Keep tenant-specific or regulated data inside the allowed region. Batch processing can also help: one scheduled update is better than dozens of tiny cross-region requests.

Set targets and separate “fast” from “okay”

Not everything needs the same speed. Treat login and core save actions as “must feel instant.” Reports, exports, and analytics can be slower if you set expectations.

Static assets are usually the easiest win. Serve JavaScript bundles and images close to users through global delivery, while keeping APIs and personal data in the residency region.

Architecture patterns that work in multi-region setups

The safest starting point is a design that keeps customer data clearly anchored to one region, while still giving you a way to recover from outages.

Active-passive vs active-active

Active-passive is usually easier to explain to auditors and customers. One region is primary for a tenant, and a secondary region is only used during failover or tightly controlled disaster recovery.

Active-active can reduce downtime and improve local speed, but it raises hard questions: which region is the source of truth, how do you prevent drift, and does replication itself count as a transfer?

A practical way to choose:

- Use active-passive when residency rules are strict, your team is small, or write volume is high.

- Use active-active only when you truly need it and your data model can handle conflicts or strong consistency.

- If customers span many countries, consider “active per tenant” (each tenant active in one region) instead of one global active-active system.

Data placement options

For databases, per-tenant regional databases are the cleanest to reason about: each tenant’s data lives in a regional Postgres instance, with controls that make cross-tenant queries hard.

If you have many small tenants, partitions can work, but only if you can guarantee partitions never leave the region and your tooling can’t accidentally run cross-region queries. Sharding by tenant or geography is often a workable middle path.

Backups and disaster recovery need an explicit rule. If backups stay in-region, restores are simpler to justify. If you copy backups to another region, document the legal basis, encryption, key location, and who can trigger a restore.

Logs and observability are where accidental transfers happen. Metrics can often be centralized if they’re aggregated and low-risk. Raw logs, traces, and error payloads may contain personal data, so keep them regional or redact aggressively.

Step-by-step rollout plan (from pilot to production)

Share and earn credits

Earn credits by sharing what you learned while building with Koder.ai.

Treat a multi-region move like a product release, not a background infrastructure change. You want written decisions, a small pilot, and evidence you can show in a review.

1) Lock requirements in writing

Capture the rules you must follow: allowed locations, in-scope data types, and what “good” looks like. Include success criteria like acceptable latency, recovery objectives, and what counts as approved cross-border access (for example, support logins).

2) Define region choice and tenant routing

Decide how each customer is placed into a region and how that choice is enforced. Keep it simple: new tenants have a default, existing tenants have an explicit assignment, and exceptions require approval. Make sure routing covers app traffic, background jobs, and where backups and logs land.

3) Build regional environments and migrate one pilot

Stand up the full stack per region: app, database, secrets, monitoring, and backups. Then migrate one pilot tenant end-to-end, including historical data. Take a snapshot before migration so you can revert cleanly.

4) Prove performance, resilience, and access controls

Run tests that match real usage and keep the results:

- Latency from your main user locations

- Failover behavior and data consistency expectations

- Admin and support access reviews (who can access what, from where)

- Alerts and audit logs you will rely on during incidents

- A short “customer questions” checklist with clear answers

5) Roll out gradually with a rollback plan

Move tenants in small batches, keep a change log, and watch error rates and support volume. For every move, have a pre-approved rollback trigger (for example, elevated errors for 15 minutes) and a practiced path back to the prior region.

Documentation that helps with audits and customer questions

Good hosting design can still fail a compliance review if you can’t explain it clearly. Treat documentation as part of the system: short, accurate, and easy to keep current.

Start with a one-page summary that a non-technical reviewer can read quickly. Say what data must stay in-region, what may leave, and why (billing, email delivery, threat detection, and so on). State your default stance in plain language: customer content stays in-region unless there’s a clear, documented exception.

Then keep two supporting artifacts current:

- A data flow diagram showing systems and arrows for data movement, including admin and support access paths

- A table listing system, data type, region, retention, who can access it, and whether it is encrypted

Add a short operations note that covers backups and restores (where backups live, retention, who can trigger restores) and an incident/support access process (approvals, logging, time-boxed access, and customer notification if required).

Make the wording customer-ready. A strong pattern is: “Stored in X, processed in Y, transfers controlled by Z.” For example: “User-generated content is stored in the EU region. Support access requires ticket approval and is logged. Aggregated metrics may be processed outside the EU but do not contain customer content.”

Keep evidence close to the docs. Save region configuration screenshots, key environment settings, and a small export of audit logs that show access approvals and any cross-region traffic controls.

Common mistakes and traps to avoid

Plan the data flow

Use Planning Mode to map data flows and systems before you ship changes.

Most problems are not about the main database. They show up in the extras around it: observability, backups, and human access. Those gaps are also what customers and auditors ask about first.

A common trap is treating logs, metrics, and traces as harmless and letting them ship to a default global region. Those records often contain user IDs, IP addresses, request payload snippets, or support notes. If app data must stay in-country, your observability data usually needs the same rule or clear redaction.

Another frequent miss is backups and disaster recovery copies. Teams claim residency based on where production runs, then forget snapshots, replicas, and restore tests. If you keep an EU primary and a US backup “just in case,” you’ve created a transfer. Make sure backup locations, retention periods, and the restore process match what you promise.

Access is the next weak spot. Global admin accounts without tight controls can break residency in practice, even if storage is correct. Use least-privilege roles, region-scoped access where possible, and audit trails that show who accessed what and from where.

Other issues that come up often include mixing tenants with different residency needs in the same database or search index, overbuilding active-active designs before you can reliably operate them, and treating “multi-region” as a slogan instead of enforced rules.

Quick checks and next steps

Before you call your setup “done,” do a fast pass that covers both compliance and real-world performance. You want to answer two questions with confidence: where does regulated data live, and what happens when something breaks.

Quick checks

Make sure each decision is tied back to your inventory and data flow map:

- You can point to a clear inventory: what data you store, where it is stored, and who can access it.

- Your data flows are mapped end-to-end (app, database, logs, analytics, support tools), and you can explain each cross-region transfer.

- Regions are chosen using written criteria (legal requirement, contract, operational needs), not just what is closest.

- Latency targets are measured in real usage, not guessed.

- Failover is tested, and you have confirmed where backups and snapshots are kept.

If you can’t answer “does support ever view production data, and from where?” you’re not ready for a customer questionnaire. Write down the support access process (roles, approval, time limits, logging) so it’s repeatable.

Next steps

Pick one customer profile and run a small pilot before a broad rollout. Choose a profile that is common and has clear residency rules (for example, “EU customer with EU-only storage”). Collect evidence you can reuse later: region settings, access logs, and failover test results.

If you want a faster way to iterate on deployments and region choices, Koder.ai (koder.ai) is a vibe-coding platform that can build and deploy apps from chat and supports deployment/hosting features like source code export and snapshots/rollback, which can be useful when you need to test changes and recover quickly during region moves.

FAQ

What’s the difference between data residency, data transfer, and data access?

Data residency is where data is stored at rest (databases, object storage, backups). Data transfer is when data crosses a border in transit (APIs, replication, exports). Data access is who can view or change data and from where.

You can satisfy residency while still creating transfers (for example, shipping logs to another region) or access concerns (support staff viewing data from another country).

Do I actually need multi-region hosting, or can I stay in one region?

Start with a single “in-region by default” setup and only add regions when you have a clear requirement (contract, regulator, public sector rule, or a customer segment you can’t sell without).

Multi-region adds cost and operational work (replication, monitoring, incident response), so it’s usually best when you can tie it to revenue or a firm compliance need.

What data needs to stay in-country, and how do I figure that out?

Treat it like an inventory problem, not a guess. List your data buckets and decide where each one is stored and processed:

- Customer content (uploads, messages)

- Account/billing data

- Metadata (IDs, timestamps, config)

- Operational data (logs, security events)

- Recovery data (backups, snapshots, replicas)

Then check every system that touches those buckets (app servers, background jobs, analytics, monitoring, email/SMS, support tools).

How do I stop logs and monitoring from breaking residency rules?

Logs are a common source of accidental cross-border transfers because they can include user IDs, IP addresses, and request snippets.

Good defaults:

- Keep raw logs/traces/error payloads in the same region as the tenant

- Redact or avoid logging sensitive fields

- Centralize only low-risk aggregated metrics

- Set clear retention limits for observability data

How should support and admin access work when staff are in other countries?

Make access rules explicit and enforce them:

- Least-privilege roles (no shared admin accounts)

- Region- or tenant-scoped access where possible

- Approval-based, time-boxed “break-glass” access for incidents

- Audit logs that show who accessed what, when, and from where

Also decide ahead of time whether remote access from other countries is allowed, and under what safeguards.

What should I do about backups, snapshots, and disaster recovery?

Backups and disaster recovery are part of the residency promise. If you store backups or replicas outside the approved area, you’ve created a transfer.

Practical approach:

- Keep backups/snapshots in-region unless you have a documented exception

- Document retention periods and deletion behavior (including backups)

- Restrict who can trigger restores

- Test restores and record where the data is pulled from

Should I choose active-passive or active-active for multi-region?

Active-passive is usually the simplest: one primary region per tenant, and a secondary region used only for controlled failover.

Active-active can improve uptime and local performance, but it adds complexity (conflict handling, consistency, and replication that may count as a transfer). If residency boundaries are strict, start with active-passive and expand only if you truly need it.

How can I keep latency reasonable without moving data out of the region?

Keep the sensitive paths local and reduce cross-region chatter:

- Run app servers, databases, and background jobs for a tenant in the same allowed region

- Avoid calling a “global” auth/session service on every request if it forces cross-region round trips

- Cache only non-sensitive or public assets globally; keep tenant-specific caches in-region

- Measure p50/p95 for a few key actions (login, dashboard load, save, search) before and after changes

What’s a safe step-by-step plan to roll out multi-region hosting?

A workable rollout is:

- Write the requirements (allowed locations, what must not leave, success metrics)

- Define tenant-to-region assignment and enforce routing for app, jobs, logs, and backups

- Stand up a full regional stack and migrate one pilot tenant end-to-end

- Test latency, failover behavior, and access controls; save evidence

- Migrate in small batches with a clear rollback trigger and a practiced rollback path

What documentation do customers and auditors usually ask for?

Keep it short and concrete. Most reviews go faster when you can answer:

- Where primary data is stored and where backups/snapshots live

- Where processing happens (app servers, background jobs, analytics, AI features)

- Which systems receive copies (monitoring, email, support tools)

- Who can access production data, from where, and with what approval

- Retention periods and how deletion works (including backups)

A one-page summary plus a simple data flow map and a system table is usually enough to start.