Nov 03, 2025·8 min

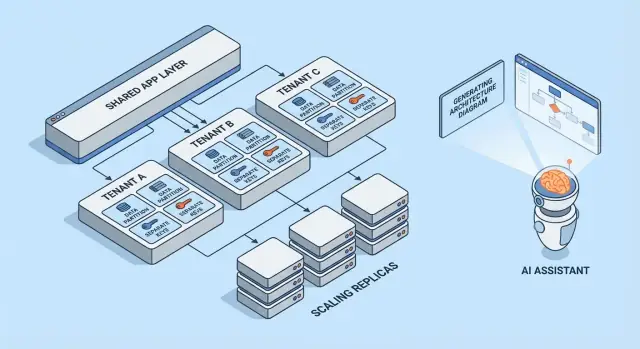

Multi-tenant SaaS Patterns: Isolation, Scale, and AI Design

Learn common multi-tenant SaaS patterns, trade-offs for tenant isolation, and scaling strategies. See how AI-generated architectures speed design and reviews.

What Multi-tenancy Means (Without the Jargon)

Multi-tenancy means one software product serves multiple customers (tenants) from the same running system. Each tenant feels like they have “their own app,” but behind the scenes they share parts of the infrastructure—like the same web servers, the same codebase, and often the same database.

A helpful mental model is an apartment building. Everyone has their own locked unit (their data and settings), but you share the building’s elevator, plumbing, and maintenance team (the app’s compute, storage, and operations).

Why teams choose multi-tenancy

Most teams don’t pick multi-tenant SaaS because it’s trendy—they pick it because it’s efficient:

- Lower cost per customer: shared infrastructure is usually cheaper than spinning up a full stack per customer.

- Simpler operations: one platform to monitor, patch, and secure (instead of hundreds of small deployments).

- Faster shipping: improvements go to everyone at once, and you avoid “version drift” across customers.

Where it can go wrong

The two classic failure modes are security and performance.

On security: if tenant boundaries aren’t enforced everywhere, a bug can leak data across customers. These leaks are rarely dramatic “hacks”—they’re often ordinary mistakes like a missing filter, a misconfigured permission check, or a background job that runs without tenant context.

On performance: shared resources mean one busy tenant can slow down others. That “noisy neighbor” effect can show up as slow queries, bursty workloads, or a single customer consuming disproportionate API capacity.

Quick preview of the patterns covered

This article walks through the building blocks teams use to manage those risks: data isolation (database, schema, or rows), tenant-aware identity and permissions, noisy-neighbor controls, and operational patterns for scaling and change management.

The Core Trade-off: Isolation vs Efficiency

Multi-tenancy is a choice about where you sit on a spectrum: how much you share across tenants versus how much you dedicate per tenant. Every architecture pattern below is just a different point on that line.

Shared vs dedicated resources: the core spectrum

At one end, tenants share almost everything: the same app instances, the same databases, the same queues, the same caches—separated logically by tenant IDs and access rules. This is typically the cheapest and easiest to run because you pool capacity.

At the other end, tenants get their own “slice” of the system: separate databases, separate compute, sometimes even separate deployments. This increases safety and control, but also increases operational overhead and costs.

Why isolation and cost pull in opposite directions

Isolation reduces the chance that one tenant can access another’s data, consume their performance budget, or be impacted by unusual usage patterns. It also makes certain audits and compliance requirements easier to satisfy.

Efficiency improves when you amortize idle capacity across many tenants. Shared infrastructure lets you run fewer servers, keep simpler deployment pipelines, and scale based on aggregate demand rather than worst-case per-tenant demand.

Common decision drivers

Your “right” point on the spectrum is rarely philosophical—it’s driven by constraints:

- SLA and customer expectations: strict uptime or latency targets push you toward more isolation.

- Compliance and data residency: requirements may force dedicated storage or dedicated environments.

- Growth stage: early products often start more shared to move faster; later you may introduce dedicated options for large customers.

- Operational maturity: more isolation usually means more things to monitor, patch, and migrate.

A simple mental model for choosing patterns

Ask two questions:

-

What’s the blast radius if one tenant misbehaves or is compromised?

-

What’s the business cost of reducing that blast radius?

If the blast radius must be tiny, choose more dedicated components. If cost and speed matter most, share more—and invest in strong access controls, rate limits, and per-tenant monitoring to keep sharing safe.

Multi-tenant Models at a Glance

Multi-tenancy isn’t one single architecture—it’s a set of ways to share (or not share) infrastructure between customers. The best model depends on how much isolation you need, how many tenants you expect, and how much operational overhead your team can handle.

1) Single-tenant (dedicated) — the baseline

Each customer gets their own app stack (or at least their own isolated runtime and database). This is the simplest to reason about for security and performance, but it’s usually the most expensive per tenant and can slow down scaling your operations.

2) Shared app + shared DB — lowest cost, highest care needed

All tenants run on the same application and database. Costs are typically lowest because you maximize reuse, but you must be meticulous about tenant context everywhere (queries, caching, background jobs, analytics exports). A single mistake can become a cross-tenant data leak.

3) Shared app + separate DB — stronger isolation, more ops

The application is shared, but each tenant has its own database (or database instance). This improves blast-radius control for incidents, enables easier tenant-level backups/restores, and can simplify compliance conversations. The trade-off is operational: more databases to provision, monitor, migrate, and secure.

4) Hybrid models for “big tenants”

Many SaaS products mix approaches: most customers live in shared infrastructure, while large or regulated tenants get dedicated databases or dedicated compute. Hybrid is often the practical end state, but it needs clear rules: who qualifies, what it costs, and how upgrades roll out.

If you want a deeper dive into isolation techniques inside each model, see /blog/data-isolation-patterns.

Data Isolation Patterns (DB, Schema, Row)

Data isolation answers a simple question: “Can one customer ever see or affect another customer’s data?” There are three common patterns, each with different security and operational implications.

Row-level isolation (shared tables + tenant_id)

All tenants share the same tables, and every row includes a tenant_id column. This is the most efficient model for small-to-mid tenants because it minimizes infrastructure and keeps reporting and analytics straightforward.

The risk is also straightforward: if any query forgets to filter by tenant_id, you can leak data. Even a single “admin” endpoint or background job can become a weak point. Mitigations include:

- Enforcing tenant filtering in a shared data-access layer (so developers don’t hand-roll filters)

- Using database features like row-level security (RLS) where available

- Adding automated tests that try cross-tenant access intentionally

- Indexing for common access paths (often

(tenant_id, created_at)or(tenant_id, id)) so tenant-scoped queries stay fast

Schema-per-tenant (same database, separate schemas)

Each tenant gets its own schema (namespaces like tenant_123.users, tenant_456.users). This improves isolation compared to row-level sharing and can make tenant export or tenant-specific tuning easier.

The trade-off is operational overhead. Migrations need to run across many schemas, and failures become more complicated: you might successfully migrate 9,900 tenants and get stuck on 100. Monitoring and tooling matter here—your migration process needs clear retry and reporting behavior.

Database-per-tenant (separate databases)

Each tenant gets a separate database. Isolation is strong: access boundaries are clearer, noisy queries from one tenant are less likely to affect another, and restoring a single tenant from backup is much cleaner.

Costs and scaling are the main drawbacks: more databases to manage, more connection pools, and potentially more upgrade/migration work. Many teams reserve this model for high-value or regulated tenants, while smaller tenants stay on shared infrastructure.

Sharding and placement strategies as tenants grow

Real systems often mix these patterns. A common path is row-level isolation for early growth, then “graduate” larger tenants into separate schemas or databases.

Sharding adds a placement layer: deciding which database cluster a tenant lives on (by region, size tier, or hashing). The key is to make tenant placement explicit and changeable—so you can move a tenant without rewriting the app, and scale by adding shards instead of redesigning everything.

Identity, Access, and Tenant Context

Multi-tenancy fails in surprisingly ordinary ways: a missing filter, a cached object shared across tenants, or an admin feature that “forgets” who the request is for. The fix isn’t one big security feature—it’s a consistent tenant context from the first byte of a request to the last database query.

Tenant identification (how you know “who”)

Most SaaS products settle on one primary identifier and treat everything else as a convenience:

- Subdomain:

acme.yourapp.comis easy for users and works well with tenant-branded experiences. - Header: useful for API clients and internal services (but must be authenticated).

- Token claim: a signed JWT (or session) includes

tenant_id, making it hard to tamper with.

Pick one source of truth and log it everywhere. If you support multiple signals (subdomain + token), define precedence and reject ambiguous requests.

Request scoping (how every query stays in-tenant)

A good rule: once you resolve tenant_id, everything downstream should read it from a single place (request context), not re-derive it.

Common guardrails include:

- Middleware that attaches

tenant_idto the request context - Data access helpers that require

tenant_idas a parameter - Database enforcement (like row-level policies) so mistakes fail closed

handleRequest(req):

tenantId = resolveTenant(req) // subdomain/header/token

req.context.tenantId = tenantId

return next(req)

Authorization basics (roles within a tenant)

Separate authentication (who the user is) from authorization (what they can do).

Typical SaaS roles are Owner / Admin / Member / Read-only, but the key is scope: a user may be an Admin in Tenant A and a Member in Tenant B. Store permissions per-tenant, not globally.

Preventing cross-tenant leaks (tests and guardrails)

Treat cross-tenant access like a top-tier incident and prevent it proactively:

- Add automated tests that try to read Tenant B data while authenticated as Tenant A

- Make missing tenant filter bugs harder to ship (linters, query builders, mandatory tenant parameters)

- Log and alert on suspicious patterns (e.g., tenant mismatch between token and subdomain)

If you want a deeper operational checklist, link these rules into your engineering runbooks at /security and keep them versioned alongside your code.

Isolation Beyond the Database

Review Tenant Security Risks

Get a threat-model checklist for cross-tenant leaks, background jobs, and caches.

Database isolation is only half the story. Many real multi-tenant incidents happen in the shared plumbing around your app: caches, queues, and storage. These layers are fast, convenient, and easy to accidentally make global.

Shared caches: prevent key collisions and data leaks

If multiple tenants share Redis or Memcached, the primary rule is simple: never store tenant-agnostic keys.

A practical pattern is to prefix every key with a stable tenant identifier (not an email domain, not a display name). For example: t:{tenant_id}:user:{user_id}. This does two things:

- Prevents collisions where two tenants have the same internal IDs

- Makes bulk invalidation feasible (delete by prefix) during support incidents or migrations

Also decide what is allowed to be shared globally (e.g., public feature flags, static metadata) and document it—accidental globals are a common source of cross-tenant exposure.

Tenant-aware rate limits and quotas

Even if data is isolated, tenants can still impact each other through shared compute. Add tenant-aware limits at the edges:

- API rate limits per tenant (and often per user within a tenant)

- Quotas for expensive operations (exports, report generation, AI calls)

Make the limit visible (headers, UI notices) so customers understand throttling is policy, not instability.

Background jobs: partition queues by tenant

A single shared queue can let one busy tenant dominate worker time.

Common fixes:

- Separate queues per tier/plan (e.g.,

free,pro,enterprise) - Partitioned queues by tenant bucket (hash tenant_id into N queues)

- Tenant-aware scheduling so each tenant gets a fair slice

Always propagate tenant context into the job payload and logs to avoid wrong-tenant side effects.

File/object storage: separate paths, policies, and keys

For S3/GCS-style storage, isolation is usually path- and policy-based:

- Bucket-per-tenant for strict separation (stronger boundaries, more overhead)

- Shared bucket with tenant prefixes (simpler, requires careful IAM and signed URLs)

Whichever you choose, enforce that uploads/downloads validate tenant ownership on every request, not just in the UI.

Handling Noisy Neighbors and Fair Resource Use

Multi-tenant systems share infrastructure, which means one tenant can accidentally (or intentionally) consume more than their fair share. This is the noisy neighbor problem: a single loud workload degrades performance for everyone else.

What “noisy neighbor” looks like

Imagine a reporting feature that exports a year of data to CSV. Tenant A schedules 20 exports at 9:00 AM. Those exports saturate CPU and database I/O, so Tenant B’s normal app screens start timing out—despite B doing nothing unusual.

Resource controls: limits, quotas, and workload shaping

Preventing this starts with explicit resource boundaries:

- Rate limits (requests per second) per tenant and per endpoint, so expensive APIs can’t be spammed.

- Quotas (daily/monthly totals) for things like exports, emails, AI calls, or background jobs.

- Workload shaping: put heavy tasks (exports, imports, re-indexing) into queues with per-tenant concurrency caps and priority rules.

A practical pattern is to separate interactive traffic from batch work: keep user-facing requests on a fast lane, and push everything else to controlled queues.

Per-tenant circuit breakers and bulkheads

Add safety valves that trigger when a tenant crosses a threshold:

- Circuit breakers: temporarily reject or defer costly operations when error rates, latency, or queue depth exceeds limits for that tenant.

- Bulkheads: isolate shared pools (DB connections, worker threads, cache) so one tenant can’t exhaust global capacity.

Done well, Tenant A can hurt their own export speed without taking down Tenant B.

When to move a tenant to dedicated capacity

Move a tenant to dedicated resources when they consistently exceed shared assumptions: sustained high throughput, unpredictable spikes tied to business-critical events, strict compliance needs, or when their workload requires custom tuning. A simple rule: if protecting other tenants requires permanent throttling of a paying customer, it’s time for dedicated capacity (or a higher tier) rather than constant firefighting.

Scaling Patterns That Work in Multi-tenant SaaS

Control Noisy Neighbors

Build per-tenant rate limits and queued jobs so noisy neighbors stay contained.

Multi-tenant scaling is less about “more servers” and more about keeping one tenant’s growth from surprising everyone else. The best patterns make scale predictable, measurable, and reversible.

Horizontal scaling for stateless services

Start by making your web/API tier stateless: store sessions in a shared cache (or use token-based auth), keep uploads in object storage, and push long-running work to background jobs. Once requests don’t depend on local memory or disk, you can add instances behind a load balancer and scale out quickly.

A practical tip: keep tenant context at the edge (derived from subdomain or headers) and pass it through to every request handler. Stateless doesn’t mean tenant-unaware—it means tenant-aware without sticky servers.

Per-tenant hotspots: identifying and smoothing them

Most scaling problems are “one tenant is different.” Watch for hotspots like:

- A single tenant generating outsized traffic

- A few tenants with very large datasets

- Batchy usage (end-of-month reports, nightly imports)

Smoothing tactics include per-tenant rate limits, queue-based ingestion, caching tenant-specific read paths, and sharding heavy tenants into separate worker pools.

Read replicas, partitioning, and async workloads

Use read replicas for read-heavy workloads (dashboards, search, analytics) and keep writes on the primary. Partitioning (by tenant, time, or both) helps keep indexes smaller and queries faster. For expensive tasks—exports, ML scoring, webhooks—prefer async jobs with idempotency so retries don’t multiply load.

Capacity planning signals and simple thresholds

Keep signals simple and tenant-aware: p95 latency, error rate, queue depth, DB CPU, and per-tenant request rate. Set easy thresholds (e.g., “queue depth > N for 10 minutes” or “p95 > X ms”) that trigger autoscaling or temporary tenant caps—before other tenants feel it.

Observability and Operations by Tenant

Multi-tenant systems don’t fail globally first—they usually fail for one tenant, one plan tier, or one noisy workload. If your logs and dashboards can’t answer “which tenant is affected?” in seconds, on-call time turns into guesswork.

Tenant-aware logs, metrics, and traces

Start with a consistent tenant context across telemetry:

- Logs: include

tenant_id,request_id, and a stableactor_id(user/service) on every request and background job. - Metrics: emit counters and latency histograms broken down by tenant tier at minimum (e.g.,

tier=basic|premium) and by high-level endpoint (not raw URLs). - Traces: propagate tenant context as trace attributes so you can filter a slow trace to a specific tenant and see where time is spent (DB, cache, third-party calls).

Keep cardinality under control: per-tenant metrics for all tenants can get expensive. A common compromise is tier-level metrics by default plus per-tenant drill-down on demand (e.g., sampling traces for “top 20 tenants by traffic” or “tenants currently breaching SLO”).

Avoiding sensitive data leaks in telemetry

Telemetry is a data export channel. Treat it like production data.

Prefer IDs over content: log customer_id=123 instead of names, emails, tokens, or query payloads. Add redaction at the logger/SDK layer, and blocklist common secrets (Authorization headers, API keys). For support workflows, store any debug payloads in a separate, access-controlled system—not in shared logs.

SLOs by tenant tier (without overpromising)

Define SLOs that match what you can actually enforce. Premium tenants might get tighter latency/error budgets, but only if you also have controls (rate limits, workload isolation, priority queues). Publish tier SLOs as targets, and track them per tier and for a curated set of high-value tenants.

On-call runbooks: common incidents in multi-tenant SaaS

Your runbooks should start with “identify affected tenant(s)” and then the fastest isolating action:

- Noisy neighbor: throttle the tenant, pause heavy jobs, or move them to a lower-priority queue.

- DB hotspots/runaway queries: enable query timeouts, inspect top queries by tenant, apply an index or limit the endpoint.

- Tenant context bugs (data mix-ups): immediately disable the feature flag or endpoint and verify tenant scoping in access checks.

- Background job pileups: drain per-tenant queues, cap concurrency, and replay with idempotency safeguards.

Operationally, the goal is simple: detect by tenant, contain by tenant, and recover without impacting everyone else.

Deployments, Migrations, and Tenant-by-Tenant Releases

Multi-tenant SaaS changes the rhythm of shipping. You’re not deploying “an app”; you’re deploying shared runtime and shared data paths that many customers depend on at once. The goal is to deliver new features without forcing a synchronized big-bang upgrade across every tenant.

Rolling deploys and low-downtime migrations

Prefer deployment patterns that tolerate mixed versions for a short window (blue/green, canary, rolling). That only works if your database changes are also staged.

A practical rule is expand → migrate → contract:

- Expand: add new columns/tables/indexes without breaking existing code.

- Migrate: backfill data in batches (often per tenant) and verify.

- Contract: remove old fields only after all app instances no longer rely on them.

For hot tables, do backfills incrementally (and throttle), otherwise you’ll create your own noisy-neighbor event during a migration.

Feature flags per tenant for safer rollouts

Tenant-level feature flags let you ship code globally while enabling behavior selectively.

This supports:

- Early access programs for a few tenants

- Fast rollback by disabling a feature for affected tenants only

- A/B experiments without forking deployments

Keep the flag system auditable: who enabled what, for which tenant, and when.

Versioning and backward compatibility expectations

Assume some tenants may lag on configuration, integrations, or usage patterns. Design APIs and events with clear versioning so new producers don’t break old consumers.

Common expectations to set internally:

- New releases must read both old and new shapes during migration windows.

- Deprecations require a published timeline (even if it’s just internal notes plus a customer email template).

Tenant-specific configuration management

Treat tenant config as product surface area: it needs validation, defaults, and change history.

Store configuration separately from code (and ideally separately from runtime secrets), and support a safe-mode fallback when config is invalid. A lightweight internal page like /settings/tenants can save hours during incident response and staged rollouts.

How AI-generated Architectures Help (and Their Limits)

Enforce Tenant Context Everywhere

Ask Koder.ai for middleware and data-access patterns that keep tenant context consistent.

AI can speed up early architecture thinking for a multi-tenant SaaS, but it’s not a substitute for engineering judgment, testing, or security review. Treat it as a high-quality brainstorming partner that produces drafts—then verify every assumption.

What AI-generated architecture should (and should not) do

AI is useful for generating options and highlighting typical failure modes (like where tenant context can be lost, or where shared resources can create surprises). It should not decide your model, guarantee compliance, or validate performance. It can’t see your real traffic, your team’s strengths, or the edge cases hidden in legacy integrations.

Inputs that matter: requirements, constraints, risks, growth

The quality of the output depends on what you feed it. Helpful inputs include:

- Tenant count today vs. in 12–24 months, and expected data volume per tenant

- Isolation requirements (contractual, regulatory, customer expectations)

- Budget and operational capacity (on-call maturity, SRE support, tooling)

- Latency targets, peak usage patterns, and burstiness by tenant

- Risk tolerance: what happens if one tenant impacts another?

Using AI to propose pattern options with trade-offs

Ask for 2–4 candidate designs (for example: database-per-tenant vs. schema-per-tenant vs. row-level isolation) and request a clear table of trade-offs: cost, operational complexity, blast radius, migration effort, and scaling limits. AI is good at listing gotchas you can turn into design questions for your team.

If you want to move from “draft architecture” to a working prototype faster, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you turn those choices into a real app skeleton via chat—often with a React frontend and a Go + PostgreSQL backend—so you can validate tenant context propagation, rate limits, and migration workflows earlier. Features like planning mode plus snapshots/rollback are especially useful when you’re iterating on multi-tenant data models.

Using AI to generate threat models and checklist items

AI can draft a simple threat model: entry points, trust boundaries, tenant-context propagation, and common mistakes (like missing authorization checks on background jobs). Use it to generate review checklists for PRs and runbooks—but validate with real security expertise and your own incident history.

A Practical Selection Checklist for Your Team

Choosing a multi-tenant approach is less about “best practice” and more about fit: your data sensitivity, your growth rate, and how much operational complexity you can carry.

Step-by-step checklist (use this in a 30-minute workshop)

-

Data: What data is shared across tenants (if any)? What must never be co-located?

-

Identity: Where does tenant identity live (invite links, domains, SSO claims)? How is tenant context established on every request?

-

Isolation: Decide your default isolation level (row/schema/database) and identify exceptions (e.g., enterprise customers needing stronger separation).

-

Scaling: Identify the first scaling pressure you expect (storage, read traffic, background jobs, analytics) and pick the simplest pattern that addresses it.

Questions to validate with engineers and security reviewers

- How do we prevent cross-tenant access if a developer forgets a filter?

- What is our audit story per tenant (who did what, when)?

- How do we handle data deletion and retention per tenant?

- What’s the blast radius of a bad migration or runaway query?

- Can we throttle, rate-limit, and budget resources per tenant?

Red flags that need deeper design work

- “We’ll add tenant checks later.”

- Shared admin tools that can see everything without strict controls.

- No plan for per-tenant backups/restore or incident response.

- A single queue/worker pool with no per-tenant fairness.

Sample “recommended next action” summary

Recommendation: Start with row-level isolation + strict tenant-context enforcement, add per-tenant throttles, and define an upgrade path to schema/database isolation for high-risk tenants.

Next actions (2 weeks): threat-model tenant boundaries, prototype enforcement in one endpoint, and run a migration rehearsal on a staging copy. For rollout guidance, see /blog/tenant-release-strategies.