Aug 14, 2025·8 min

Niklas Zennström, Skype, and Viral Growth pre-iPhone

A clear look at how Skype spread through viral sharing, low-cost calling, and network effects—plus the trade-offs that shaped it before smartphones.

A clear look at how Skype spread through viral sharing, low-cost calling, and network effects—plus the trade-offs that shaped it before smartphones.

Skype’s early growth is one of the clearest examples of a product becoming a habit through everyday usefulness—not advertising budgets. Long before “growth loops” became a standard slide in pitch decks, Skype showed that a communication tool could spread person to person (and keep spreading) simply because each new user made the product more valuable for everyone else.

A big part of that story starts with Niklas Zennström, Skype’s co-founder and early strategist. Coming off the experience of building consumer internet products in Europe, Zennström helped shape Skype around a simple promise: make calling over the internet feel normal, trustworthy, and close enough to the phone that anyone could try it. The choices made in those early years—what to give away, what to charge for, and how to design the product to invite others—still map cleanly to modern product growth thinking.

Traditional phone calling was expensive (especially across borders) and controlled by carriers. Skype flipped the feeling: calls could be free, setup didn’t require a contract, and you could see who was online and reach them instantly. That “I can just call you” moment made communication feel more casual—closer to a conversation than a transaction.

Understanding Skype means remembering how people discovered software in the early 2000s: downloads, email, chat, and recommendations—not app stores and push notifications. Distribution depended on users sharing links, inviting friends, and solving a real problem right away on a laptop or desktop. Constraints were harsher, which makes Skype’s growth signals even more instructive.

You’ll see how Skype combined:

The result wasn’t just rapid sign-ups—it was repeat usage that turned Skype into a default verb for internet calling.

Skype didn’t invent the desire to talk across distance. It ran straight into everyday frustrations people already felt, but had learned to tolerate.

International calling in the early 2000s was still priced like a luxury. Per‑minute charges made “quick catch-ups” feel risky, and bills often arrived as unpleasant surprises. Even domestic long-distance could add up, especially for students, immigrants, remote workers, and anyone with family in another country.

The result was a communication pattern built around scarcity: call less often, keep calls short, and save “real conversations” for special occasions.

Most users were comfortable with email and instant messaging: asynchronous, cheap, and predictable. You could message multiple people, paste links, and avoid interrupting someone’s day. But these tools didn’t fully replace voice—especially when emotion, nuance, or urgency mattered.

So the expectation was clear: communication should be near-free, easy to initiate, and compatible with existing habits (contact lists, presence, quick follow-ups).

Broadband adoption on home PCs meant more households had “always-on” connectivity, headsets, and enough bandwidth for real-time audio. The phone line stopped being the default channel for voice—your computer could plausibly become the calling device.

Installing new software from the internet wasn’t a casual decision. Users worried about scams, spyware, and the awkwardness of talking to strangers. Skype’s core problem wasn’t only technical—it also had to feel safe and familiar enough that people would try it, then invite someone they cared about.

Skype’s rise looks almost compressed when you map it against the early-2000s internet. It went from a niche download to a default verb (“Just Skype me”) while most people still thought of calling as something you did through a phone company.

Skype’s growth wasn’t powered by abstract tech—it was powered by very human needs:

These scenarios created repeat usage because the value wasn’t occasional; it was social and ongoing.

Skype spread through communities that were already international: diaspora networks, universities, open-source and tech forums, and globally distributed teams. One person installed it for a specific relationship, then pulled in the other side of that relationship—often in another country—creating a natural referral loop.

Before smartphones, being huge meant being installed on millions of PCs and becoming the default way to reach someone when email was too slow and phone calls were too expensive. “Always-on” wasn’t about a device in your pocket—it was about a presence on your desktop and in your contact list.

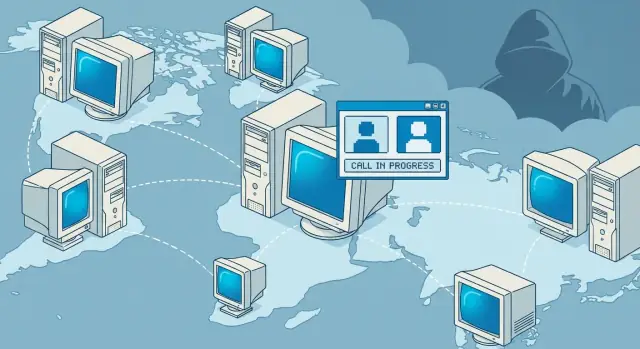

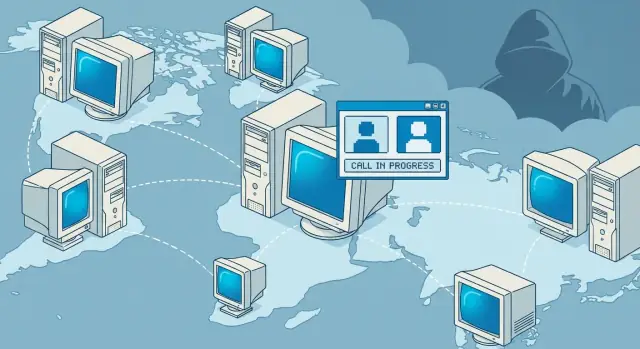

Skype’s breakout wasn’t just clever marketing. The product was built on a peer-to-peer (P2P) architecture that fit the early 2000s internet—and turned technical decisions into visible user benefits.

In a traditional phone or VoIP calling setup, your voice goes through central servers owned by the provider. With peer-to-peer communication, parts of the “work” are shared across the network of users. Your Skype app could connect more directly to other Skype apps, instead of relying on one big, expensive hub for everything.

For non-technical users, the takeaway was simple: Skype calls often worked even when the service was growing fast, because the system didn’t depend on a single bottleneck.

Bandwidth and server infrastructure were costly, and home connections were uneven. By leaning on P2P, Skype could scale call setup and routing in ways that reduced how much centralized capacity it needed per new user. That mattered for viral distribution: as more people joined, the network could handle more conversations without Skype having to buy proportionally more servers.

This architecture also supported Skype’s global promise. International calling and cross-border communication became more accessible because the marginal cost of connecting two people was lower than in a fully centralized model.

Many people were behind home routers and firewalls that broke early VoIP tools. Skype invested heavily in making calling work through common network obstacles. Users didn’t have to learn what NAT, ports, or router settings were—calls simply connected.

That “it just works” moment is a growth feature: fewer failed setups means more successful first calls, more referrals, and stronger referral loops.

P2P wasn’t magic. Quality could vary with network conditions, and reliability sometimes depended on factors outside the user’s control. Updates were frequent and occasionally disruptive, because the system needed many clients to stay compatible. Some users also noticed higher CPU or bandwidth usage during calls.

Still, this product architecture gave Skype its signature advantage: it made global VoIP calling feel straightforward at a time when the internet wasn’t.

Skype didn’t spread because people wanted “a better VoIP app.” It spread because one person wanted to talk to one specific person—and the fastest way to make that happen was to get the other person to install Skype.

The referral wasn’t an abstract recommendation; it was a practical instruction. If you were traveling, living abroad, or calling family long-distance, the value was immediate and personal. “Download Skype so we can talk for free” is a clearer pitch than any ad.

That made sharing feel like coordination, not marketing. The reward arrived instantly: your first call—no points, no waiting, no complicated incentives.

Skype turned the address book into distribution. Once you installed, the next step was naturally to find people you already knew.

Presence (seeing who was online) made invites feel timely: if a friend appeared available, you had a reason to message or call right then. And if they weren’t on Skype yet, the absence itself created a prompt to invite—because the product was literally more useful when your contacts were inside it.

“Free-to-try” isn’t the same as “free and complete.” Skype’s core use case—Skype-to-Skype calling—delivered full value at $0. That removed the biggest hesitation in early-2000s software: paying upfront for something you weren’t sure would work on your computer and internet connection.

Viral loops break when the first experience is confusing. Skype reduced early failure points with:

When the first call sounded “good enough,” users immediately pulled in the next person—one relationship at a time.

Skype wasn’t just “useful software.” It became useful because other people you cared about were on it. That’s the core network effect: every new user increased the number of possible free calls for everyone else.

A photo editor is valuable the moment you install it. A calling app is different: its value is proportional to who you can reach. When your contacts joined Skype, your “address book of reachable people” expanded—and your reason to keep Skype installed grew.

Phone calls are naturally two-sided. If you started a Skype call with a friend overseas, you didn’t just create one active user—you created (or reactivated) two. Many first-time users arrived because someone they trusted said, “Download Skype, it’s free.” The callee wasn’t an audience; they were the next node in the network.

Skype didn’t need hard lock-in to earn repeat usage. Once your family group, your project team, or your long-distance relationship settled on Skype, the “cost” of switching was social coordination: convincing everyone to move at once, re-adding contacts, and rebuilding habits. You could leave, but you’d be leaving behind the easiest path to the people you call.

Network effects often felt sudden:

That’s the flywheel: invitations create reachable contacts, reachable contacts create repeat calls, and repeat calls create more invitations.

Skype’s monetization worked because it didn’t put a toll booth in front of the core behavior: talking to someone who also had Skype.

The simplest split was: Skype-to-Skype calls were free, while calls from Skype to regular phone numbers cost money (SkypeOut). Free calls maximized adoption and kept the “invite a friend” loop frictionless. Paid calling targeted a different job: reaching people who weren’t on Skype yet—family members, clients, hotels, landlines, and international numbers.

Communication is inherently social: one person can’t get full value alone. Freemium lets users experience real utility immediately (a clear call, a familiar contact list, a working conversation) before they ever consider paying. That matters because trust builds through repeated use—especially with something as personal as voice.

By monetizing interoperability (calling “outside” the Skype network) rather than participation (joining it), Skype protected the top of the funnel. Users could download, test, and invite others without a credit card. When a need appeared—“I need to call a phone right now”—the upgrade felt situational and practical, not forced.

Freemium also introduces pitfalls:

Skype’s challenge was to keep the free experience obvious and delightful, while making paid options understandable at the exact moment users needed them.

Skype’s promise sounded simple: voice calls that felt “normal,” just cheaper and easier across borders. But users didn’t judge it like a new internet gadget—they judged it against the phone. That meant three expectations mattered most: clarity, low delay, and consistency from one call to the next.

Early-2000s calling happened in imperfect conditions. People used bargain headsets, built-in laptop mics, or a shared family PC in a noisy room. Many connections ran over congested home broadband, and later, shaky home Wi‑Fi. The result was predictable: echo, jitter, dropped calls, and the classic “Can you hear me now?” loop.

Skype couldn’t control everyone’s setup, so it had to make uncertainty feel manageable.

Trust often came from “boring” UI details that reduced anxiety mid-call:

Together, these features turned inevitable glitches into something users could explain and fix—crucial for repeat usage.

A consumer app spreading virally also spreads confusion and abuse cases. As Skype scaled, it faced support pressure from users who blamed the product for hardware problems, ISP throttling, or misconfigured audio drivers. At the same time, safety issues grew: spam contact requests, impersonation, and unwanted calls.

Quality and trust weren’t just engineering goals—they were growth constraints. If the first call felt unreliable or unsafe, the referral loop broke. Skype’s long-term win required treating “messy reality” as a core product surface, not an edge case.

Skype’s growth message worked because it was easy to repeat and instantly relevant: call anyone, anywhere. You didn’t need to understand peer-to-peer communication or VoIP calling to get the value. If you had family abroad, a long‑distance partner, a distributed team, or friends from travel, the promise explained itself in one sentence.

“Free” or “cheap” is only persuasive when people can picture the moment they’ll use it. Skype’s messaging naturally mapped to high-emotion, high-frequency situations—birthdays, quick check-ins, job interviews, study abroad—where international phone charges felt unfair.

That made the product easy to recommend without sounding like a tech pitch. Instead of “try this app,” the invitation was closer to: “Download Skype so we can talk without the bill.”

Cross-border products win when they feel local. Skype’s message didn’t require perfect cultural translation because the pain point was shared globally.

Still, adoption often happened through specific international communities:

Each group carried the message into different languages and contexts, while keeping the same simple promise.

Even when users cared about video or chat, “cheap international calling” became a memorable referral line—short, practical, and easy to justify. It gave people a reason to invite others, and it gave invitees a reason to accept.

Skype also benefited from visibility through everyday channels: mentions in mainstream tech coverage, distribution partnerships, and word-of-mouth sparked by notable product updates. None of that replaces a great product—but it amplifies a message that already travels well across borders.

Skype didn’t become a habit because it was novel—it became a habit because it solved recurring, emotional problems for specific groups. The strongest repeat usage came from people who had a reason to call again tomorrow.

Expats and international families were the clearest win. When “call home” costs drop from dollars per minute to essentially free, a monthly check-in can turn into a weekly ritual. That repeat cadence mattered: it kept contact lists fresh and made Skype the default place to see who’s around.

Remote teams were another early driver. Before modern collaboration suites, Skype became the meeting room: quick voice calls, ad‑hoc screen sharing later on, and a simple roster of who was online. For small distributed teams, reliability wasn’t a nice-to-have—it was their workflow.

Online sellers and freelancers used Skype as a trust tool. Hearing a real voice reduced uncertainty in cross-border deals, and it created a lightweight way to handle customer questions without publishing a personal phone number.

Gamers brought a different kind of repeat usage: high-frequency sessions. They weren’t scheduling “a call”; they were staying connected during play.

Many small businesses treated Skype as a budget PBX: a shared account on a front-desk computer, a few usernames for staff, and paid calling for edge cases. It wasn’t polished, but it worked—and it was easy to try.

A subtle behavior shift helped retention: Skype made calling feel more like messaging. Seeing someone online encouraged spontaneous “got a minute?” conversations.

These use cases spread through everyday needs, not marketing channels. Download links traveled via email and chat, and value was proven in the first real conversation—then repeated because the user’s life demanded it.

Skype’s breakout years were shaped by the PC-first environment. “Install a program” was a normal step, and the hardware assumptions were different: a desktop or laptop that stayed online for long stretches, plus a cheap headset or USB microphone that turned a computer into a usable phone. Many early users first experienced VoIP through a shared family PC, an office workstation, or an internet café—places where long sessions and stable power weren’t a concern.

Before app stores, the entire acquisition funnel had more friction. You had to:

That friction made word-of-mouth even more valuable: a recommendation didn’t just create awareness, it justified the effort and the trust required to install software.

When calling moved onto smartphones, the constraints changed. Users expected the app to be lightweight, sip battery, behave well on limited data, and “just work” in the background with push notifications. The PC-era pattern—leave Skype running all day—didn’t translate cleanly to a phone that people actively managed to preserve battery life.

Skype’s original strengths (PC presence, broadband at home/work, peer-to-peer efficiency, and a download-first growth model) were less differentiated once distribution consolidated into app stores and mobile platforms tightened control over background activity and networking. The same sharing instinct still mattered—but the channels, constraints, and default user behavior shifted underneath it.

Skype’s story isn’t just “viral growth happened.” It’s a set of deliberate product choices—many still relevant whether you’re building a consumer app, a marketplace, or a B2B tool.

Skype didn’t bolt on referrals later. The product’s main job—calling—often required another person to join. That made the “invite-to-call” a natural step, not a marketing interruption.

If your product has a collaboration, handoff, or “we should do this together” moment, make sharing the shortest path to success.

Retention wasn’t just about features; it was about relationships. Contacts, presence (“online/offline”), and a familiar identity created a reason to return.

A practical check: does each new user make the product more useful for existing users? If yes, ensure those connections are visible and easy to re-engage.

VoIP calling was compelling because it delivered immediate savings and utility. Monetization (like paid calling to phones) came after users trusted the experience.

Freemium works best when:

Real-time communication amplifies the cost of bugs, spam, and confusion. Quality, safety, and customer support aren’t “later-stage” work—they’re growth features.

If you want viral distribution and network effects, build guardrails early: clear identity, anti-abuse controls, and fast recovery when calls fail.

A modern way to pressure-test these ideas is to prototype the user journey end-to-end—invite flow, contact graph, onboarding, and upgrade moments—before you commit months of engineering. Teams building new communication or collaboration products sometimes do this in Koder.ai, a vibe-coding platform where you can iterate through those loops in a chat-driven workflow, generate a React web app with a Go + PostgreSQL backend, and quickly validate whether your “shareable moment” and retention surfaces actually hold together.

For a deeper dive on growth mechanics, see /blog/referral-loops.

Skype grew because the core action (calling) naturally required another person. Every successful call created the next invite: “download it so we can talk.” That made sharing feel like coordination, not promotion, and each new user increased the product’s value for existing users.

Viral distribution is how new users arrive (invites, word-of-mouth embedded in the product). Network effects are why users stay (the product becomes more valuable as more of your contacts join). Skype combined both: invites drove installs, and a growing contact list drove repeat calling.

In the early 2000s, users had to find a download link, run an installer, and trust unknown software—often with manual updates later. That extra friction made personal recommendations far more powerful, because a friend’s invite also provided the trust needed to install and try the product.

Skype’s first “aha” was making internet calling feel normal: install, add a contact, place a call that sounds good enough. Practical tactics for modern products:

Presence turned calling into a lightweight, everyday behavior. Seeing “Online/Away/On a call” helped users choose the right time to reach out, and it encouraged spontaneous “got a minute?” calls—more like messaging than formal phone calling.

Peer-to-peer (P2P) helped Skype scale without relying on one central bottleneck for every call. Practically, that translated to user-visible benefits:

Skype removed early blockers that would kill referrals:

For modern teams, treat onboarding reliability as a growth lever, not just UX polish.

Skype kept Skype-to-Skype calling free (where network effects matter most) and charged for calling regular phone numbers (interoperability). That preserves growth because users can join, try, and invite others without payment—then pay only when they need to reach someone outside the network.

Viral growth amplifies abuse and confusion, so trust becomes a constraint. Common issues included spam contact requests, impersonation, and users blaming Skype for hardware/ISP problems. Practical guardrails:

Design the product so sharing is the shortest path to success, and make connections visible:

If you’re mapping loops, a useful next step is documenting your referral paths and failure points (see /blog/referral-loops).