Aug 07, 2025·8 min

Noam Shazeer and the Transformer Architecture Behind LLMs

Learn how Noam Shazeer helped shape the Transformer: self-attention, multi-head attention, and why this design became the backbone of modern LLMs.

Learn how Noam Shazeer helped shape the Transformer: self-attention, multi-head attention, and why this design became the backbone of modern LLMs.

A Transformer is a way to help computers understand sequences—things where order and context matter, like sentences, code, or a series of search queries. Instead of reading one token at a time and carrying a fragile memory forward, Transformers look across the whole sequence and decide what to pay attention to when interpreting each part.

That simple shift turned out to be a big deal. It’s a major reason modern large language models (LLMs) can hold onto context, follow instructions, write coherent paragraphs, and generate code that references earlier functions and variables.

If you’ve used a chatbot, a “summarize this” feature, semantic search, or a coding assistant, you’ve interacted with Transformer-based systems. The same core blueprint supports:

We’ll break down the key parts—self-attention, multi-head attention, positional encoding, and the basic Transformer block—and explain why this design scales so well as models get larger.

We’ll also touch on modern variants that keep the same core idea but tweak it for speed, cost, or longer context windows.

This is a high-level tour with plain-language explanations and minimal math. The goal is to build intuition: what the pieces do, why they work together, and how that translates into real product capabilities.

Noam Shazeer is an AI researcher and engineer best known as one of the co-authors of the 2017 paper “Attention Is All You Need.” That paper introduced the Transformer architecture, which later became the foundation for many modern large language models (LLMs). Shazeer’s work sits within a team effort: the Transformer was created by a group of researchers at Google, and it’s important to credit it that way.

Before the Transformer, many NLP systems relied on recurrent models that processed text step-by-step. The Transformer proposal showed that you could model sequences effectively without recurrence by using attention as the main mechanism for combining information across a sentence.

That shift mattered because it made training easier to parallelize (you can process many tokens at once), and it opened the door to scaling models and datasets in a way that quickly became practical for real products.

Shazeer’s contribution—alongside the other authors—didn’t stay confined to academic benchmarks. The Transformer became a reusable module that teams could adapt: swap components, change the size, tune it for tasks, and later pretrain it at scale.

This is how many breakthroughs travel: a paper introduces a clean, general recipe; engineers refine it; companies operationalize it; and eventually it becomes a default choice for building language features.

It’s accurate to say Shazeer was a key contributor and co-author of the Transformer paper. It’s not accurate to frame him as the sole inventor. The impact comes from the collective design—and from the many follow-on improvements the community built on top of that original blueprint.

Before Transformers, most sequence problems (translation, speech, text generation) were dominated by Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and later LSTMs (Long Short-Term Memory networks). The big idea was simple: read text one token at a time, keep a running “memory” (a hidden state), and use that state to predict what comes next.

An RNN processes a sentence like a chain. Each step updates the hidden state based on the current word and the previous hidden state. LSTMs improved this by adding gates that decide what to keep, forget, or output—making it easier to hold onto useful signals for longer.

In practice, sequential memory has a bottleneck: a lot of information must be squeezed through a single state as the sentence gets longer. Even with LSTMs, signals from far earlier words can fade or get overwritten.

This made certain relationships difficult to learn reliably—like linking a pronoun to the correct noun many words back, or keeping track of a topic across multiple clauses.

RNNs and LSTMs are also slow to train because they can’t fully parallelize over time. You can batch across different sentences, but within one sentence, step 50 depends on step 49, which depends on step 48, and so on.

That step-by-step computation becomes a serious limitation when you want bigger models, more data, and faster experimentation.

Researchers needed a design that could relate words to each other without marching strictly left-to-right during training—a way to model long-distance relationships directly and take better advantage of modern hardware. This pressure set the stage for the attention-first approach introduced in Attention Is All You Need.

Attention is the model’s way of asking: “Which other words should I look at right now to understand this word?” Instead of reading a sentence strictly left to right and hoping the memory holds, attention lets the model peek at the most relevant parts of the sentence at the moment it needs them.

A helpful mental model is a tiny search engine running inside the sentence.

So, the model forms a query for the current position, compares it to the keys of all positions, and then retrieves a blend of values.

Those comparisons produce relevance scores: rough “how related is this?” signals. The model then turns them into attention weights, which are proportions that add up to 1.

If one word is very relevant, it gets a larger share of the model’s focus. If several words matter, attention can spread across them.

Take: “Maria told Jenna that she would call later.”

To interpret she, the model should look back at candidates like “Maria” and “Jenna.” Attention assigns higher weight to the name that best fits the context.

Or consider: “The keys to the cabinet are missing.” Attention helps link “are” to “keys” (the true subject), not “cabinet,” even though “cabinet” is closer. That’s the core benefit: attention links meaning across distance, on demand.

Self-attention is the idea that each token in a sequence can look at other tokens in that same sequence to decide what matters right now. Instead of processing words strictly left-to-right (as older recurrent models did), the Transformer lets every token gather clues from anywhere in the input.

Imagine the sentence: “I poured the water into the cup because it was empty.” The word “it” should connect to “cup,” not “water.” With self-attention, the token for “it” assigns higher importance to tokens that help resolve its meaning (“cup,” “empty”) and lower importance to irrelevant ones.

After self-attention, each token is no longer just itself. It becomes a context-aware version—a weighted blend of information from other tokens. You can think of it as each token creating a personalized summary of the whole sentence, tuned to what that token needs.

In practice, this means the representation for “cup” can carry signals from “poured,” “water,” and “empty,” while “empty” can pull in what it describes.

Because each token can compute its attention over the full sequence at the same time, training doesn’t have to wait for previous tokens to be processed step-by-step. This parallel processing is a major reason Transformers train efficiently on large datasets and scale up to huge models.

Self-attention makes it easier to connect distant parts of text. A token can directly focus on a relevant word far away—without passing information through a long chain of intermediate steps.

That direct path helps with tasks like coreference (“she,” “it,” “they”), keeping track of topics across paragraphs, and handling instructions that depend on earlier details.

A single attention mechanism is powerful, but it can still feel like trying to understand a conversation by watching only one camera angle. Sentences often contain several relationships at once: who did what, what “it” refers to, which words set the tone, and what the overall topic is.

When you read “The trophy didn’t fit in the suitcase because it was too small,” you may need to track multiple clues at the same time (grammar, meaning, and real-world context). One attention “view” might lock onto the closest noun; another might use the verb phrase to decide what “it” refers to.

Multi-head attention runs several attention calculations in parallel. Each “head” is encouraged to look at the sentence through a different lens—often described as different subspaces. In practice, that means heads can specialize in different patterns, such as:

After each head produces its own set of insights, the model doesn’t choose just one. It concatenates the head outputs (stacking them side by side) and then projects them back into the model’s main “working space” with a learned linear layer.

Think of it as merging several partial notes into one clean summary the next layer can use. The result is a representation that can capture many relationships at once—one of the reasons Transformers work so well at scale.

Self-attention is great at spotting relationships—but by itself it doesn’t know who came first. If you shuffle the words in a sentence, a plain self-attention layer can treat the shuffled version as equally valid, because it compares tokens without any built-in sense of position.

Positional encoding solves this by injecting “where am I in the sequence?” information into the token representations. Once position is attached, attention can learn patterns like “the word right after not matters a lot” or “the subject usually appears before the verb” without having to infer order from scratch.

The core idea is simple: each token embedding is combined with a position signal before it enters the Transformer block. That position signal can be thought of as an extra set of features that tag a token as 1st, 2nd, 3rd… in the input.

There are a few common approaches:

Positional choices can noticeably affect long-context modeling—things like summarizing a long report, tracking entities across many paragraphs, or retrieving a detail mentioned thousands of tokens earlier.

With long inputs, the model isn’t just learning language; it’s learning where to look. Relative and rotary-style schemes tend to make it easier to compare far-apart tokens and preserve patterns as context grows, while some absolute schemes can degrade more quickly when pushed beyond their training window.

In practice, positional encoding is one of those quiet design decisions that can shape whether an LLM feels sharp and consistent at 2,000 tokens—and still coherent at 100,000.

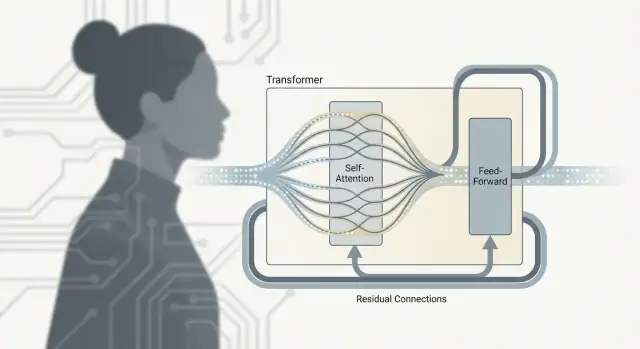

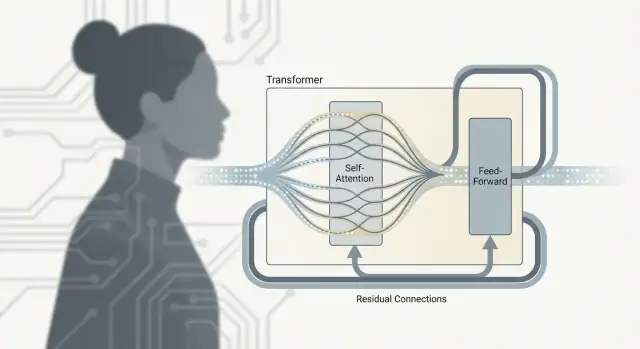

A Transformer isn’t just “attention.” The real work happens inside a repeating unit—often called a Transformer block—that mixes information across tokens and then refines it. Stack many of these blocks and you get the depth that makes large language models so capable.

Self-attention is the communication step: each token gathers context from other tokens.

The feed-forward network (FFN), also called an MLP, is the thinking step: it takes each token’s updated representation and runs the same small neural network on it independently.

In plain terms, the FFN transforms and reshapes what each token now knows, helping the model build richer features (like syntax patterns, facts, or style cues) after it has collected relevant context.

The alternation matters because the two parts do different jobs:

Repeating this pattern lets the model gradually build higher-level meaning: communicate, compute, communicate again, compute again.

Each sub-layer (attention or FFN) is wrapped with a residual connection: the input is added back to the output. This helps deep models train because gradients can flow through the “skip lane” even if a particular layer is still learning. It also lets a layer make small adjustments instead of having to relearn everything from scratch.

Layer normalization is a stabilizer that keeps activations from drifting too large or too small as they pass through many layers. Think of it as keeping the volume level consistent so later layers don’t get overwhelmed or starved of signal—making training smoother and more reliable, especially at LLM scale.

The original Transformer in Attention Is All You Need was built for machine translation, where you convert one sequence (French) into another (English). That job naturally splits into two roles: reading the input well, and writing the output fluently.

In an encoder–decoder Transformer, the encoder processes the entire input sentence at once and produces a rich set of representations. The decoder then generates the output one token at a time.

Crucially, the decoder doesn’t rely only on its own past tokens. It also uses cross-attention to look back at the encoder’s output, helping it stay grounded in the source text.

This setup is still excellent when you must tightly condition on an input—translation, summarization, or question answering with a specific passage.

Most modern large language models are decoder-only. They’re trained to do a simple, powerful task: predict the next token.

To make that work, they use masked self-attention (often called causal attention). Each position can attend only to earlier tokens, not future ones, so generation stays consistent: the model writes left-to-right, continually extending the sequence.

This is dominant for LLMs because it’s straightforward to train on massive text corpora, it matches the generation use-case directly, and it scales efficiently with data and compute.

Encoder-only Transformers (like BERT-style models) don’t generate text; they read the whole input bidirectionally. They’re great for classification, search, and embeddings—anything where understanding a piece of text matters more than producing a long continuation.

Transformers turned out to be unusually scale-friendly: if you give them more text, more compute, and bigger models, they tend to keep improving in a predictable way.

A big reason is structural simplicity. A Transformer is built from repeated blocks (self-attention + a small feed-forward network, plus normalization), and those blocks behave similarly whether you’re training on a million words or a trillion.

Earlier sequence models (like RNNs) had to process tokens one-by-one, which limits how much work you can do at once. Transformers, by contrast, can process all tokens in a sequence in parallel during training.

That makes them a great fit for GPUs/TPUs and large distributed setups—exactly what you need when training modern LLMs.

The context window is the chunk of text the model can “see” at one time—your prompt plus any recent conversation or document text. A larger window lets the model connect ideas across more sentences or pages, keep track of constraints, and answer questions that depend on earlier details.

But context is not free.

Self-attention compares tokens with each other. As the sequence gets longer, the number of comparisons grows quickly (roughly with the square of the sequence length).

That’s why very long context windows can be expensive in memory and compute, and why many modern efforts focus on making attention more efficient.

When Transformers are trained at scale, they don’t just get better at one narrow task. They often start to show broad, flexible capabilities—summarizing, translating, writing, coding, and reasoning—because the same general learning machinery is applied across massive, varied data.

The original Transformer design is still the reference point, but most production LLMs are “Transformers plus”: small, practical edits that keep the core block (attention + MLP) while improving speed, stability, or context length.

Many upgrades are less about changing what the model is and more about making it train and run better:

These changes usually don’t alter the fundamental “Transformer-ness” of the model—they refine it.

Extending context from a few thousand tokens to tens or hundreds of thousands often relies on sparse attention (only attend to selected tokens) or efficient attention variants (approximate or restructure attention to cut computation).

The trade-off is typically a mix of accuracy, memory, and engineering complexity.

MoE models add multiple “expert” sub-networks and route each token through only a subset. Conceptually: you get a larger brain, but you don’t activate all of it every time.

This can lower compute per token for a given parameter count, but it increases system complexity (routing, balancing experts, serving).

When a model touts a new Transformer variant, ask for:

Most improvements are real—but they’re rarely free.

Transformer ideas like self-attention and scaling are fascinating—but product teams mostly feel them as trade-offs: how much text you can feed in, how quickly you get an answer back, and what it costs per request.

Context length: Longer context lets you include more documents, chat history, and instructions. It also increases token spend and can slow responses. If your feature relies on “read these 30 pages and answer,” prioritize context length.

Latency: User-facing chat and copilot experiences live or die on response time. Streaming output helps, but model choice, region, and batching also matter.

Cost: Pricing is usually per token (input + output). A model that’s 10% “better” may be 2–5× the cost. Use pricing-style comparisons to decide what quality level is worth paying for.

Quality: Define it for your use case: factual accuracy, instruction-following, tone, tool-use, or code. Evaluate with real examples from your domain, not generic benchmarks.

If you mainly need search, deduplication, clustering, recommendations, or “find similar”, embeddings (often encoder-style models) are typically cheaper, faster, and more stable than prompting a chat model. Use generation only for the final step (summaries, explanations, drafting) after retrieval.

For a deeper breakdown, link your team to a technical explainer like /blog/embeddings-vs-generation.

When you turn Transformer capabilities into a product, the hard part is usually less about the architecture and more about the workflow around it: prompt iteration, grounding, evaluation, and safe deployment.

One practical route is using a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai to prototype and ship LLM-backed features faster: you can describe the web app, backend endpoints, and data model in chat, iterate in planning mode, and then export source code or deploy with hosting, custom domains, and rollback via snapshots. That’s especially useful when you’re experimenting with retrieval, embeddings, or tool-calling loops and want tight iteration cycles without rebuilding the same scaffolding each time.

A Transformer is a neural network architecture for sequence data that uses self-attention to relate every token to every other token in the same input.

Instead of carrying information step-by-step (like RNNs/LSTMs), it builds context by deciding what to pay attention to across the whole sequence, which improves long-range understanding and makes training more parallel-friendly.

RNNs and LSTMs process text one token at a time, which makes training harder to parallelize and creates a bottleneck for long-range dependencies.

Transformers use attention to connect distant tokens directly, and they can compute many token-to-token interactions in parallel during training—making them faster to scale with more data and compute.

Attention is a mechanism for answering: “Which other tokens matter most for understanding this token right now?”

You can think of it like in-sentence retrieval:

The output is a weighted blend of relevant tokens, giving each position a context-aware representation.

Self-attention means the tokens in a sequence attend to other tokens in the same sequence.

It’s the core tool that lets a model resolve things like coreference (e.g., what “it” refers to), subject–verb relationships across clauses, and dependencies that appear far apart in the text—without pushing everything through a single recurrent “memory.”

Multi-head attention runs multiple attention calculations in parallel, and each head can specialize in different patterns.

In practice, different heads often focus on different relationships (syntax, long-range links, pronoun resolution, topical cues). The model then combines these views so it can represent several kinds of structure at once.

Self-attention alone doesn’t inherently know token order—without position information, word shuffles can look similar.

Positional encodings inject order signals into token representations so the model can learn patterns like “what comes right after not matters” or typical subject-before-verb structure.

Common options include sinusoidal (fixed), learned absolute positions, and relative/rotary-style methods.

A Transformer block typically combines:

The original Transformer is encoder–decoder:

Most LLMs today are models trained to predict the next token using , which matches left-to-right generation and scales well on large corpora.

Noam Shazeer was a co-author on the 2017 paper “Attention Is All You Need,” which introduced the Transformer.

It’s accurate to credit him as a key contributor, but the architecture was created by a team at Google, and its impact also comes from many later community and industry improvements built on that original blueprint.

For long inputs, standard self-attention becomes expensive because comparisons grow roughly with the square of sequence length, impacting memory and compute.

Practical ways teams handle this include:

Stacking many blocks yields the depth that enables richer features and stronger behavior at scale.