Aug 22, 2025·8 min

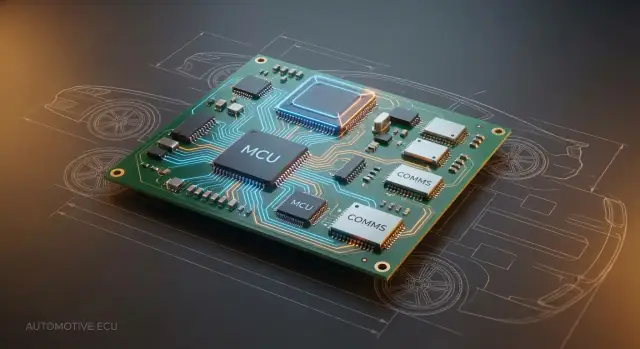

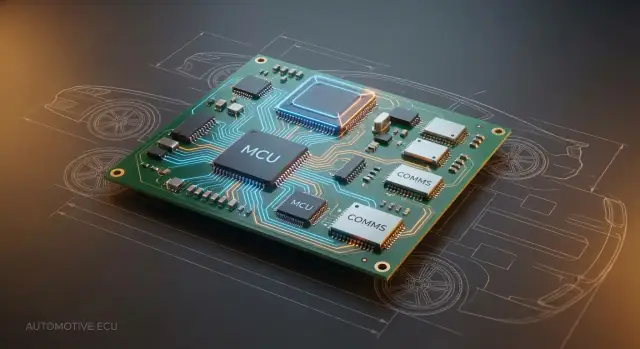

NXP Semiconductors: Why Automotive Chips Stick for Years

See how long design cycles, safety standards, and validation work make NXP automotive and embedded chips difficult to swap once they are designed in.

See how long design cycles, safety standards, and validation work make NXP automotive and embedded chips difficult to swap once they are designed in.

“Sticky” is a practical way to describe a chip that’s hard to replace once it’s been chosen for a product. In automotive semiconductors and many embedded systems, the first selection isn’t just a purchase decision—it’s a long-term commitment that can last for a vehicle program (and sometimes beyond).

A chip becomes sticky because it gets “designed in.” Engineers connect it to power rails, sensors, memory, and communications; write and validate firmware; tune timing and performance; and prove that the full electronic control unit (ECU microcontroller plus surrounding components) behaves predictably. After that investment, swapping the silicon isn’t like switching a part on a spreadsheet. It can ripple through hardware, software, safety documents, testing, and the production line.

Consumer electronics often tolerate faster refresh cycles and looser change control. If a phone uses a different component next year, the whole device generation changes anyway.

Vehicles and industrial products are the opposite: they’re expected to stay in production for years, keep working in harsh conditions, and remain serviceable. That makes long product lifecycles and supply commitments central to the chip choice—one reason suppliers like NXP Semiconductors can remain in designs for a long time once they’re qualified.

This piece focuses on the process and incentives that create stickiness, not hidden supplier negotiations or confidential program details. The goal is to show why “switching costs” are often dominated by engineering time, risk, and validation effort rather than the unit price of the chip.

Across automotive and embedded systems, the same themes keep showing up: long design-in cycles, functional safety requirements (often aligned with ISO 26262), qualification and reliability expectations (such as AEC-Q100), extensive validation, and software ecosystems that are expensive to rebuild. In the next sections, we’ll walk through each of these forces and how they lock a design in place.

Automotive chips don’t “stick” because engineers hate change—they stick because the path from an idea to a vehicle on the road has multiple gates, and each gate increases the cost of swapping parts.

Concept and requirements: A new ECU (electronic control unit) is defined. Teams set targets for performance, power, cost, interfaces (CAN/LIN/Ethernet), security, and safety goals.

Supplier selection and architecture: A short list of silicon options is evaluated. This is where companies like NXP Semiconductors often compete on features, tool support, and long-term availability.

Prototype builds: Early boards and firmware are created. The microcontroller, power components, and network transceivers are integrated and validated together.

Pre-production and industrialization: The design is tuned for manufacturing, test coverage, and reliability margins.

Start of production (SOP): Once the vehicle program is launched, changes become slow, heavily documented, and expensive.

A design win means a specific chip is chosen for a specific customer program (for example, an ECU in a vehicle platform). It’s a commercial milestone, but it also signals technical commitment: boards are laid out around that part, software is written to its peripherals, and validation evidence accumulates. After a design win, switching isn’t impossible—but it’s rarely “just a swap.”

In practice, Tier 1s make many of the chip-level choices, but OEM standards, approved vendor lists, and platform reuse heavily influence what gets selected—and what stays locked in.

Car programs don’t move on the same cadence as consumer electronics. A vehicle platform is typically planned, engineered, validated, and launched over several years—then sold (often with updates) for several more. That long runway pushes teams to pick components they can support for the full platform life, not just for the first production run.

Once an ECU microcontroller is selected and proven, it’s usually cheaper and safer to keep it than to reopen the decision.

A “platform” isn’t a single car. The same underlying electronics architecture is reused across trims, body styles, and model years, and sometimes across brands within a group. That reuse is intentional:

If a chip is designed into one high-volume ECU, it can end up copied across multiple programs. That multiplication effect makes switching later much more disruptive.

Changing a microcontroller late in the program is not a simple parts swap. Even when the new silicon is “pin-compatible,” teams still face knock-on work:

Those steps collide with fixed gates (build events, supplier tooling, homologation deadlines), so a late change can slip schedules or force parallel versions.

Vehicles must be repairable for years. OEMs and Tier 1s need continuity for service parts, warranty repairs, and replacement ECUs that match the original behavior. A stable chip platform simplifies spare inventory, workshop procedures, and long-term support—another reason automotive semiconductors tend to stay in place for a long time once they’re validated and in production.

Functional safety, in plain language, is about reducing the risk that a system failure could cause harm. In a car, that can mean making sure a fault in an ECU microcontroller doesn’t lead to unintended acceleration, loss of steering assist, or a disabled airbag.

For automotive electronics, this is typically managed under ISO 26262. The standard doesn’t just ask teams to “build it safely”—it asks them to prove, with evidence, how safety risks were identified, reduced, verified, and kept under control over time.

Safety work creates a paper trail by design. Requirements must be documented, linked to design decisions, linked again to tests, and tied back to hazards and safety goals. This traceability matters because when something goes wrong (or when an auditor asks), you need to show exactly what was intended and exactly what was verified.

Testing also grows in scope. It’s not only “does it work,” but also “does it fail safely,” “what happens when sensors glitch,” and “what if the MCU clock drifts.” That means more test cases, more coverage expectations, and more recorded results that must remain consistent with the shipped configuration.

A safety concept is the plan for how the system will stay safe—what safety mechanisms exist, where redundancy is used, what diagnostics run, and how the system reacts to faults.

A safety case is the organized argument that the plan was implemented correctly and validated. It’s the bundle of reasoning and evidence—documents, analyses, test reports—that supports the claim: “this ECU meets its safety goals.”

Once a chip is selected, the safety concept often becomes intertwined with that specific silicon: watchdogs, lockstep cores, memory protection, diagnostic features, and vendor safety manuals.

If you switch the component, you don’t just swap a part number. You may need to redo analyses, update traceability links, re-run large portions of verification, and rebuild the safety case. That time, cost, and certification risk is a major reason automotive semiconductors tend to “stick” for years.

Choosing an automotive chip isn’t just about performance and price. Before a part can be used in a vehicle program, it typically needs to be automotive-qualified—a formal proof that it can survive years of heat, cold, vibration, and electrical stress without drifting out of spec.

A common shorthand you’ll hear is AEC-Q100 (for integrated circuits) or AEC-Q200 (for passive components). You don’t need to memorize the test list to understand the impact: it’s a widely recognized qualification framework that suppliers use to show a device behaves predictably under automotive conditions.

For OEMs and Tier 1s, that label is a gate. A non-qualified alternative might be fine in a lab or prototype, but it can be hard to justify for a production ECU microcontroller or safety-critical power device, especially when audits and customer requirements are involved.

Cars place components in places consumer electronics never go: under-hood, near powertrain heat, or in sealed modules with limited airflow. That’s why requirements often include:

Even when a chip seems “equivalent,” the qualified version may use different silicon revisions, packaging, or manufacturing controls to hit those expectations.

Switching a chip late in a program can trigger re-testing, documentation updates, and sometimes new board spins. That work can delay SOP dates and pull engineering teams away from other milestones.

The result is a strong incentive to stay with a proven, already-qualified platform once it’s cleared the qualification hurdle—because repeating the process is expensive, slow, and full of schedule risk.

A microcontroller in an ECU isn’t “just hardware.” Once a team designs in a specific MCU family, they also adopt an entire software environment that tends to fit that chip’s peripherals, memory layout, and timing behavior.

Even simple functions—CAN/LIN communication, watchdogs, ADC readings, PWM motor control—depend on vendor-specific drivers and configuration tools. Those pieces gradually become woven into the project:

When you swap the chip, you rarely “recompile and ship.” You port and re-validate.

If the program uses AUTOSAR (Classic or Adaptive), the microcontroller choice influences the Microcontroller Abstraction Layer (MCAL), Complex Device Drivers, and the configuration tooling that generates large parts of the software stack.

Middleware adds another layer of coupling: crypto libraries tied to hardware security modules, bootloaders designed for a specific flash architecture, RTOS ports tuned for that core, diagnostic stacks that expect certain timers or CAN features. Each dependency might have a supported-chip list—and switching can trigger renegotiations with vendors, new integration work, and new licensing or validation steps.

Automotive programs run for years, so teams value toolchains and documentation that remain stable. A chip isn’t attractive only because it’s fast or cheap; it’s attractive because:

The most expensive part of changing microcontrollers is often invisible on a BOM spreadsheet:

Porting low-level code, redoing timing analysis, regenerating AUTOSAR configs, re-qualifying diagnostics, re-running regression tests, repeating parts of functional safety evidence, and validating behavior across temperature/voltage corners. Even if the new chip looks “compatible,” proving that the ECU still behaves safely and predictably is real schedule and engineering cost—one reason software ecosystems make chip choices stick.

Choosing an ECU microcontroller or network transceiver isn’t just picking “a chip.” It’s choosing how a board talks, powers up, stores data, and behaves electrically under real vehicle conditions.

Interface decisions set the wiring, topology, and gateway strategy early. A design centered on CAN and LIN looks very different from one built around Automotive Ethernet, even if both run similar application software.

Common choices like CAN, LIN, Ethernet, I2C, and SPI also dictate:

Once those choices are routed and validated, swapping to a different part can trigger changes well beyond the bill of materials.

Even when two parts seem comparable on a datasheet, the pinout rarely matches perfectly. Different pin functions, package sizes, and boot configuration pins can force a PCB re-layout.

Power is another lock-in point. A new MCU might need different voltage rails, tighter sequencing, new regulators, or different decoupling and grounding strategies. Memory needs can also bind you to a family: internal Flash/RAM sizes, external QSPI Flash support, ECC requirements, and how memory is mapped can all affect both hardware and startup behavior.

Automotive EMC/EMI results can change with a new chip because edge rates, clocking, spread-spectrum options, and driver strengths differ. Signal integrity on Ethernet, CAN, or fast SPI links may require re-tuning terminations, routing constraints, or common-mode chokes.

A true drop-in replacement means matching package, pinout, power, clocks, peripherals, and electrical behavior closely enough that safety, EMC, and manufacturing tests still pass. In practice, teams often find that a “compatible” chip is compatible only after redesign and revalidation—exactly what they were trying to avoid.

Automakers don’t pick an ECU microcontroller only for its performance today—they pick it for the decade (or more) of obligations that follow. Once a platform is awarded, the program needs predictable availability, stable specifications, and a clear plan for what happens when parts, packages, or processes change.

Automotive programs are built around guaranteed supply. Vendors like NXP Semiconductors often publish longevity programs and PCN (Product Change Notification) processes so OEMs and Tier 1s can plan around the realities of wafer capacity, foundry moves, and component allocation. The commitment isn’t just “we’ll sell it for years”; it’s also “we’ll manage change slowly and transparently,” because even small revisions can trigger re-validation.

After SOP (start of production), most work shifts from new features to sustaining engineering. That means keeping the bill of materials buildable, monitoring quality and reliability, addressing errata, and executing controlled changes (for example, alternate assembly sites or revised test flows). In contrast, new development is where teams can still reconsider architecture and suppliers.

Once sustaining engineering dominates, the priority becomes continuity—another reason chip choices stay “sticky.”

Second-sourcing can reduce risk, but it’s rarely as simple as “drop-in replacement.” Pin-to-pin alternatives may differ in safety documentation, peripheral behavior, toolchains, timing, or memory characteristics. Even when a second source exists, qualifying it can require additional AEC-Q100 evidence, software regression, and functional safety rework under ISO 26262—costs many teams would rather avoid unless supply pressure forces the issue.

Vehicle programs typically require years of production supply plus an extended tail for spare parts and service. That service horizon influences everything from last-time-buy planning to storage and traceability policies. When a chip platform already aligns with those long product lifecycles, it becomes the path of least risk—and the hardest to replace later.

Automotive gets the headlines, but the same “stickiness” shows up across embedded markets—especially where downtime is expensive, compliance is mandatory, and products stay in service for a decade or more.

In industrial automation, a controller or motor drive might run 24/7 for years. A surprise component change can trigger revalidation of timing, EMC behavior, thermal margins, and field reliability. Even if the new chip is “better,” the work to prove it’s safe for the line often outweighs the benefit.

That’s why factories tend to favor stable MCU and SoC families (including long-lived NXP Semiconductors lines) with predictable pinouts, long-term supply programs, and incremental performance upgrades. It lets teams reuse boards, safety cases, and test fixtures rather than restarting from scratch.

Medical devices face strict regulatory documentation and verification requirements. Changing an embedded processor can mean re-running verification plans, updating cybersecurity documentation, and repeating risk analysis—time that delays shipments and ties up quality teams.

Infrastructure and utilities have a different pressure: uptime. Substations, smart meters, and communication gateways are deployed at scale and expected to work reliably in harsh environments. A component swap isn’t just a BOM change; it can require new environmental testing, firmware requalification, and coordinated field rollout planning.

Across these markets, platform stability is a feature:

The result mirrors automotive design-in dynamics: once an embedded chip family is qualified in a product line, teams tend to keep building on it—sometimes for many years—because the real cost is not the silicon, but the evidence and confidence wrapped around it.

Automotive teams don’t swap an ECU microcontroller lightly, but it does happen—usually when external pressure outweighs the cost of change. The key is to treat a swap as a mini-program, not a purchasing decision.

Common triggers include:

The best mitigation starts before the first prototype. Teams often define early alternates (pin-compatible or software-compatible options) during the design-in cycle, even if they never build them into production. They also push for modular hardware (separate power, comms, and compute where feasible) so a chip change doesn’t force a full PCB redesign.

On the software side, abstraction layers help: isolate chip-specific drivers (CAN, LIN, Ethernet, ADC, timers) behind stable interfaces so application code stays mostly untouched. This is especially valuable when moving between MCU families—even within a vendor portfolio—because tooling and low-level behavior still differ.

A practical note: a lot of the overhead in a switch is coordination—tracking what changed, what must be re-tested, and what evidence is impacted. Some teams reduce this friction by building lightweight internal tools (change-control dashboards, test-tracking portals, audit checklists). Platforms like Koder.ai can help here by letting you generate and iterate on these web apps via a chat interface, then export source code for review and deployment—useful when you need a custom workflow quickly without derailing the main ECU engineering schedule.

A swap isn’t just “does it boot?” You must re-run large portions of verification: timing, diagnostics, fault handling, and safety mechanisms (e.g., ISO 26262 work products). Each change triggers documentation updates, traceability checks, and re-approval cycles, plus weeks of regression testing across temperature, voltage, and edge cases.

Consider a switch only if you can answer “yes” to most of these:

Automotive and embedded chips “stick” because the decision isn’t just about silicon performance—it’s about committing to a platform that must remain stable for years.

First, the design-in cycle is long and expensive. Once an ECU microcontroller is selected, teams build schematics, PCBs, power design, EMC work, and validation around that exact part. Changing it later can trigger a chain reaction of rework.

Second, safety and compliance raise the switching costs. Meeting functional safety expectations (often aligned with ISO 26262) involves documentation, safety analysis, tool qualification, and controlled processes. Reliability expectations (commonly tied to AEC-Q100 and customer-specific test plans) add more time and evidence. The chip isn’t “approved” until the whole system is.

Third, software cements the choice. Drivers, middleware, bootloaders, security modules, AUTOSAR stacks, and internal test suites are written and tuned for a specific family. Porting is possible, but it is rarely free—and regressions are hard to tolerate in safety-related systems.

For suppliers like NXP Semiconductors, this stickiness can translate into steadier, more forecastable demand once a program enters production. Vehicle programs and embedded products often run for many years, and continuity of supply planning becomes part of the relationship—not an afterthought.

Long lifecycles can also slow down upgrades. Even when a new node, feature, or architecture looks compelling, the “cost to change” may outweigh the benefits until a major platform refresh.

If you want to go deeper, browse related posts at /blog, or see how commercial terms can affect platform choices on /pricing.

In this context, “sticky” means a semiconductor that’s difficult and costly to replace after it has been selected for an ECU or embedded product. Once it’s designed in (hardware connections, firmware, safety evidence, tests, and manufacturing flow), changing it tends to trigger broad rework and schedule risk.

Because the chip choice becomes part of a long-lived system that must remain stable for years.

A design win is when a specific chip is selected for a specific customer program (for example, an ECU on a vehicle platform). Practically, it signals that teams will:

The best windows are early, before work becomes locked in:

ISO 26262 drives a disciplined process to reduce safety risk and prove it with traceable evidence. If you change the microcontroller, you may need to revisit:

A safety concept is the plan for staying safe (diagnostics, redundancies, fault reactions). A safety case is the structured argument—backed by documents, analyses, and test reports—that the concept was implemented and validated.

Switching silicon often means updating both, because the evidence is tied to specific chip features and vendor guidance.

AEC-Q100 is a commonly used automotive qualification framework for integrated circuits. It matters because it acts like a gate for production use: OEMs and Tier 1s rely on it (and related reliability expectations) to ensure a device can survive automotive stresses like temperature cycling and electrical transients.

Choosing a non-qualified alternative can create approval and audit hurdles.

Because the chip decision also selects a software environment:

Even “compatible” hardware usually requires porting plus extensive regression testing.

Hardware integration is rarely a “BOM-only” change. A new part can force:

That risk is a major reason true drop-in replacements are uncommon.

Switching typically happens when external pressure outweighs the engineering and validation cost, such as:

Teams reduce risk by planning alternates early, using modular hardware where possible, and isolating chip-specific code behind abstraction layers—then budgeting time for re-validation and documentation updates.