Nov 21, 2025·8 min

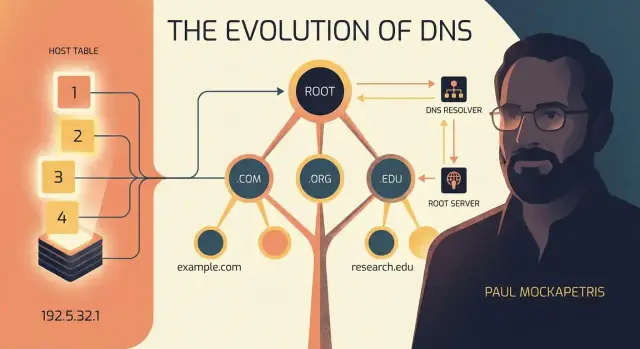

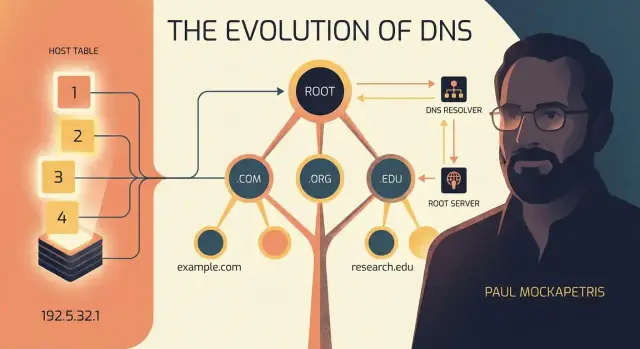

Paul Mockapetris and DNS: How the Internet Got Human Names

Learn how Paul Mockapetris created DNS, replacing unwieldy host lists with a scalable naming system. See how DNS works, why caching matters, and key security basics.

Learn how Paul Mockapetris created DNS, replacing unwieldy host lists with a scalable naming system. See how DNS works, why caching matters, and key security basics.

Every time you type a web address, click a link, or send an email, you’re relying on a simple idea: humans should be able to use memorable names, while computers do the work of finding the right machine.

DNS solves an everyday problem: computers communicate using numerical addresses (IP addresses) like 203.0.113.42, but people don’t want to memorize strings of numbers. You want to remember example.com, not whatever address that site happens to use today.

The Domain Name System (DNS) is the internet’s “address book” that translates human-friendly domain names into the IP addresses computers use to connect.

That translation sounds small, but it’s the difference between an internet that feels usable and one that feels like a phone directory written entirely in digits.

This is a non-technical tour—no networking background required. We’ll walk through:

Along the way, you’ll meet Paul Mockapetris, the engineer who designed DNS in the early 1980s. His work mattered because he didn’t just create a new naming format—he designed a system that could scale as the internet expanded from a small research network into something used by billions of people.

If you’ve ever had a site “go down,” waited for a domain change to “propagate,” or wondered why email settings include mysterious DNS entries, you’ve already met DNS from the outside. The rest of this article explains what’s happening behind the scenes—clearly, and without the jargon.

Long before anyone typed a familiar web address, early networks had a simpler problem: how do you reach a specific machine? Computers could talk to each other using IP addresses (numbers like 10.0.0.5), but humans preferred hostnames—short labels like MIT-MC or SRI-NIC that were easier to remember and share.

For the early ARPANET, the solution was a single shared file called HOSTS.TXT. It was essentially a lookup table: a list of hostnames paired with their IP addresses.

Each computer kept a local copy of this file. If you wanted to connect to a machine by name, your system checked HOSTS.TXT and found the corresponding IP address.

This worked at first because the network was small, changes were relatively rare, and there was a clear place to get updates.

As more organizations joined, the approach started to buckle under normal growth:

The core issue was coordination. HOSTS.TXT was like one shared address book for the entire world. If everyone depends on the same book, every correction requires a global edit, and everyone has to download the newest version quickly. Once the network reached a certain size, that “one file for everything” model became too slow, too centralized, and too error-prone.

DNS didn’t replace the idea of mapping names to numbers—it replaced the fragile way that mapping was maintained and distributed.

In the early 1980s, the internet was shifting from a small research network into something bigger, messier, and more widely shared. More machines were joining, organizations wanted autonomy, and people needed an easier way to reach services than memorizing numeric addresses.

Paul Mockapetris, working in that environment, is widely credited as the designer of DNS. His contribution wasn’t a flashy product—it was an engineering answer to a very practical question: how do you keep names usable when the network keeps growing?

A naming system sounds simple until you picture what “simple” meant back then: one shared list of names that everyone had to download and keep up to date. That approach breaks as soon as change becomes constant. Every new host, rename, or correction turns into coordination work for everyone.

Mockapetris’ key insight was that names aren’t just data; they’re shared agreements. If the network expands, the system for making and distributing those agreements must expand too—without requiring every computer to constantly fetch a master list.

DNS replaced the idea of “one authoritative file” with a distributed design:

That’s the quiet brilliance: DNS wasn’t designed to be clever; it was designed to keep working under real constraints—limited bandwidth, frequent changes, many independent admins, and a network that refused to stop growing.

DNS wasn’t invented as a clever shortcut—it was designed to solve specific, very practical problems that showed up as the early Internet grew. Mockapetris’ approach was to set clear goals first, then build a naming system that could keep up for decades.

The key concept is delegation: different groups manage different parts of the name tree.

For example, one organization manages what’s under .com, a registrar helps you claim example.com, and then you (or your DNS provider) control the records for www.example.com, mail.example.com, and so on. This splits responsibility cleanly, so growth doesn’t create a bottleneck.

DNS assumes problems will happen—servers crash, networks partition, routes change. So it relies on multiple authoritative servers for a domain and on caching in resolvers, so a temporary outage doesn’t immediately break every lookup.

DNS translates human-friendly names into technical data, most famously IP addresses. It’s not “the Internet itself”—it’s a naming and lookup service that helps your devices find where to connect.

DNS makes names manageable by organizing them like a tree. Instead of one giant list where every name must be unique globally (and someone has to police it), DNS breaks naming into levels and delegates responsibility.

A DNS name is read from right to left:

www.example.com. technically ends with a ..com, .org, .net, country codes like .ukexample in example.comwww in www.example.comSo www.example.com can be broken into:

com (the TLD)example (the domain registered under .com)www (a label the domain owner creates and controls)This structure reduces conflicts because names only need to be unique within their parent. Many organizations can have a www subdomain, because www.example.com and www.another-example.com don’t collide.

It also spreads the workload. The .com operators don’t need to manage every website’s records; they only point to who is responsible for example.com, and then the example.com owner manages the details.

A zone is simply a manageable piece of that tree—DNS data someone is responsible for publishing. For many teams, “our zone” means “the DNS records for example.com and whatever subdomains we host,” stored on their authoritative DNS provider.

When you type a website name into a browser, you’re not asking “the internet” directly. A few specialized helpers split the work so the answer can be found quickly and reliably.

You (your device and browser) start with a simple request: “What IP address matches example.com?” Your device usually doesn’t know the answer yet, and it doesn’t want to call a dozen servers to find out.

A recursive resolver does the searching on your behalf. This is typically provided by your ISP, your workplace/school IT, or a public resolver. The key benefit: it can reuse cached answers from previous lookups, speeding things up for everyone using it.

Authoritative DNS servers are the source of truth for a domain. They don’t “search” the internet; they hold the official records that say which IPs, mail servers, or verification tokens belong to that domain.

example.com.Think of the recursive resolver as a librarian who can look things up for you (and remembers popular answers), while an authoritative server is the publisher’s official catalog: it doesn’t browse other catalogs—it simply states what’s true for its own books.

When you type example.com into your browser, your browser isn’t actually looking for a name—it needs an IP address (a number like 93.184.216.34) to know where to connect. DNS is the “find me the number for this name” system.

Your browser first asks your computer/phone’s operating system: “Do we already know the IP address for example.com?” The OS checks its own short-term memory (cache). If it finds a fresh answer, the lookup ends here.

If the OS doesn’t have it, it forwards the question to a DNS resolver—usually run by your ISP, your company, or a public provider. Think of the resolver as your “DNS concierge”: it does the legwork so your device doesn’t have to.

If the resolver doesn’t have the answer cached, it starts a guided search:

.com). The root server doesn’t give the final IP—it gives referrals, basically directions: “Ask these .com servers next.”.com): The resolver asks the .com servers where example.com is handled. Again, not the final IP—more directions: “Ask this authoritative server for example.com.”A or AAAA record) containing the IP address.The resolver sends the IP back to your OS, then to your browser, which can finally connect. Most lookups feel instant because resolvers and devices cache answers for a period set by the domain owner (TTL).

A straightforward flow to remember is: Browser → OS cache → Resolver cache → Root (referral) → TLD (referral) → Authoritative (answer) → back to Browser.

DNS would feel painfully slow if every visit to a website required starting from scratch and asking multiple servers for the same answer. Instead, DNS relies on caching—temporary “memory” of recent lookups—so most users get answers in milliseconds.

When your device asks a DNS resolver for example.com, that resolver may need to do some work the first time. After it learns the answer, it stores it in a cache. The next person who asks for the same name can be answered immediately.

Caching exists for two reasons:

Every DNS record is served with a TTL (Time To Live) value. Think of TTL as instructions that say: keep this answer for X seconds, then discard it and ask again.

If a record has a TTL of 300, resolvers may reuse it for up to 5 minutes before re-checking.

TTL is a balancing act:

If you’re moving a website to a new host, switching a CDN, or doing an email cutover (changing MX records), TTL determines how quickly users stop going to the old place.

A common approach is to lower TTLs in advance of a planned change, make the switch, then raise TTLs again once everything is stable. That’s why DNS can be fast day-to-day—and why it can feel “stubborn” right after an update.

When you log into a DNS dashboard, you’ll mostly be editing a handful of record types. Each record is a small instruction that tells the internet where to send people (web), where to deliver mail, or how to verify ownership.

| Record | What it does | Simple example |

|---|---|---|

| A | Points a name to an IPv4 address | example.com → 203.0.113.10 (your website server) |

| AAAA | Points a name to an IPv6 address | example.com → 2001:db8::10 (same idea, newer addressing) |

| CNAME | Makes one name an alias of another name | www.example.com → example.com (so both go to the same place) |

| MX | Tells where email for the domain should go | example.com → mail.provider.com (priority 10) |

| TXT | Stores “notes” machines can read (verification, email policy) | example.com has an SPF record like v=spf1 include:mailgun.org ~all |

| NS | Says which authoritative servers host DNS for a domain/zone | example.com → ns1.dns-host.com |

| SOA | The zone’s “header”: primary NS, admin contact, and timing values | example.com SOA includes ns1.dns-host.com and retry/expire timers |

A few DNS errors show up again and again:

example.com). Many DNS providers don’t allow it because the root name must also carry records like NS and SOA. If you need “root to a hostname,” use an A/AAAA record or an “ALIAS/ANAME” feature if your provider supports it.www). Pick one approach.mail.provider.com can break email; missing/extra dots and copying the wrong host field (e.g., @ vs www) is a common cause of outages.If you’re sharing DNS guidance with a team, a small table like the one above in your docs (or a runbook page) makes reviews and troubleshooting much faster.

DNS works because responsibility is split across many organizations. That split is also why you can move providers, change settings, and keep your name online without asking “the internet” for permission.

Registering a domain is buying the right to use a name (like example.com) for a period of time. Think of it as reserving a label so nobody else can claim it.

DNS hosting is running the settings that tell the world where that name should point—your website, email provider, verification records, and so on. You can register a domain with one company and host DNS with another.

.com, .org, or .uk. It maintains the official database of who holds each name under that TLD and which name servers are responsible for it.Root servers sit at the top of DNS. They don’t know your website’s IP address and they don’t store your domain’s records. Their job is narrower: they tell resolvers where to find the authoritative servers for each TLD (like where .com is handled).

When you set “name servers” for your domain at your registrar, you’re creating a delegation. The .com registry (via its authoritative servers) will then point queries for example.com to the name servers you chose.

From that moment, those name servers control the answers the rest of the internet receives—until you change the delegation again.

DNS is built on trust: when you type a name, you assume the answer points to the real service. Most of the time it does—but DNS is also a favorite place to attack, because a small change in “where this name goes” can redirect lots of people.

One classic issue is spoofing or cache poisoning. If an attacker can trick a DNS resolver into storing a fake answer, users may be sent to the wrong IP address even when they typed the correct domain. The result can be phishing pages, malware downloads, or intercepted traffic.

Another problem is domain hijacking at the registrar level. If someone gets into your registrar account, they can change name servers or DNS records and effectively “take over” your domain without touching your website hosting.

Then there’s the everyday danger: misconfigurations. A stray CNAME, an old TXT record, or an incorrect MX record can break login flows, email delivery, or verification checks. These failures often look like “the internet is down,” but the root cause is a small DNS edit.

DNSSEC adds cryptographic signatures to DNS data. In plain terms: the DNS answer can be validated to confirm it hasn’t been altered in transit and that it truly came from the domain’s authoritative DNS. DNSSEC doesn’t encrypt DNS or hide what you’re looking up, but it can prevent many kinds of forged answers from being accepted.

Traditional DNS queries are easy for networks to observe. DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) and DNS-over-TLS (DoT) encrypt the connection between your device and a resolver, reducing snooping and some on-path tampering. They don’t magically make DNS “anonymous,” but they do change who can see and manipulate queries.

Use MFA on your registrar, enable domain/transfer locks, and restrict who can edit DNS. Treat DNS changes like production deployments: require review, keep a change log, and set up monitoring/alerts for record or name server changes so you learn about surprises quickly.

DNS can feel like “set it and forget it,” until a small change knocks out your website or email. The good news: a few habits make DNS management predictable—even for small teams.

Start with a lightweight process you can repeat:

Most DNS problems aren’t complicated—they’re just hard to notice quickly.

If you deploy apps frequently, DNS becomes part of your release process. For example, teams shipping web apps from platforms like Koder.ai (where you can build and deploy apps via chat, then attach custom domains) still rely on the same fundamentals: correct A/AAAA/CNAME targets, sensible TTLs during cutovers, and a clear rollback path if something points to the wrong place.

If you send email from your domain, DNS directly affects whether messages reach inboxes.

Human-friendly names made the internet scale beyond a small research community. Treat DNS like shared infrastructure—small care upfront keeps your site reachable and your email trusted as you grow.

DNS (Domain Name System) translates human-friendly names like example.com into IP addresses like 93.184.216.34 so your device knows where to connect.

Without DNS, you’d have to remember numeric addresses for every site and service you use.

Early networks relied on a single shared file (HOSTS.TXT) that mapped names to IP addresses.

As the network grew, it became unmanageable: constant updates, conflicting names, and outages caused by outdated copies. DNS replaced the “one global file” approach with a distributed system.

Paul Mockapetris designed DNS in the early 1980s to solve the scaling problem of naming on a rapidly growing network.

The key idea was delegation: split responsibility across many organizations so no single master list (or administrator) becomes a bottleneck.

DNS names are hierarchical and read right-to-left:

www.example.com..comexample.comwww.example.comThis hierarchy makes delegation and management practical at global scale.

A recursive resolver looks up answers on your behalf and caches them (often run by an ISP, workplace, or public provider).

An authoritative DNS server is the source of truth for a domain’s records; it doesn’t “search,” it answers for its zone.

A typical lookup goes like this:

.com) → the domain’s authoritative servers.A/).TTL (Time To Live) tells resolvers how long they may cache a DNS answer before checking again.

“Propagation” is mostly just caches expiring at different times.

The most common records you’ll manage are:

A registrar is where you register/renew the domain name (your right to use example.com).

A DNS host/provider runs the authoritative name servers and stores your DNS records.

You can mix-and-match: register with one company and host DNS elsewhere by changing the domain’s NS (name server) settings at the registrar.

DNS can fail due to:

MX, conflicting records, typos)Practical defenses:

AAAAAAAAACNAME: alias one hostname to another (common for www).MX: where email for the domain should be delivered.TXT: verification and email auth (SPF, DKIM, DMARC).NS: which name servers are authoritative for the domain.A practical rule: don’t put both CNAME and A records on the same hostname.