Nov 28, 2025·8 min

Pierre Omidyar and eBay: Liquidity, Trust, and Moats

Learn how Pierre Omidyar built eBay by pairing marketplace liquidity with reputation. See how trust, feedback, and incentives create durable moats.

Learn how Pierre Omidyar built eBay by pairing marketplace liquidity with reputation. See how trust, feedback, and incentives create durable moats.

eBay is more than an internet nostalgia story. It’s one of the clearest, longest-running case studies of a marketplace that kept working as categories shifted, competitors copied features, and user expectations rose. For founders and product teams building two-sided marketplaces today, eBay matters because it shows what actually compounds over time—and what doesn’t.

At a high level, eBay’s durability comes down to three pillars that reinforce each other:

A marketplace isn’t just a website with listings. It’s a system for helping the right buyer find the right seller at the right moment, with enough confidence to transact. Search, categorization, payments, shipping workflows, and dispute handling are not “extras”—they are the core machinery that reduces friction on both sides.

eBay treated trust like something you can design and measure, not just hope for. Feedback scores, ratings, seller history, and policies turned “Can I trust this stranger?” into a set of signals users could act on quickly. That’s a product advantage, not merely a community nicety.

Liquidity is the probability that a buyer finds what they want and a seller makes a sale within a reasonable time. When liquidity is high, users return without being pushed. When it’s low, no amount of marketing copy saves the experience.

A defensible marketplace is hard to copy and easy to grow. Hard to copy because competitors can replicate UI, but they can’t instantly replicate accumulated trust signals, repeat buyers, and the dense matching that makes the market feel “alive.” Easy to grow because each successful transaction makes the next transaction more likely.

This article translates eBay’s lessons into practical takeaways: how to bootstrap liquidity without damaging trust, how to design reputation that users believe, and where network effects actually live in a marketplace.

Pierre Omidyar didn’t set out to build a grand “platform strategy.” He noticed something simpler: strangers wanted a way to trade directly with each other online, and they needed a lightweight system that made those trades feel safe enough to repeat.

eBay’s early product idea was straightforward: anyone could list an item, other people could bid, and the market would decide the price. That structure did two important things at once.

First, it made selling accessible—no catalog, no inventory, no “approved merchants.” Second, auctions solved the awkward question of “what is this worth?” when the item didn’t have a standard retail price.

Collectibles and long-tail goods were a strong starting niche because they’re hard to price and hard to find locally.

A vintage watch part, a discontinued toy, or a regional baseball card might have only a handful of real buyers—but those buyers are scattered. Bringing them together in one place creates real value quickly. Auctions also fit the psychology of collectors: scarcity, excitement, and a clear mechanism for settling disputes over value without the seller needing to be an expert appraiser.

This post isn’t a founder-myth retelling or a timeline of corporate milestones. Instead, it focuses on the mechanics that made early eBay work:

Omidyar’s early insight matters because it frames eBay less as an “auction site,” and more as a repeatable system for making trade between strangers feel normal.

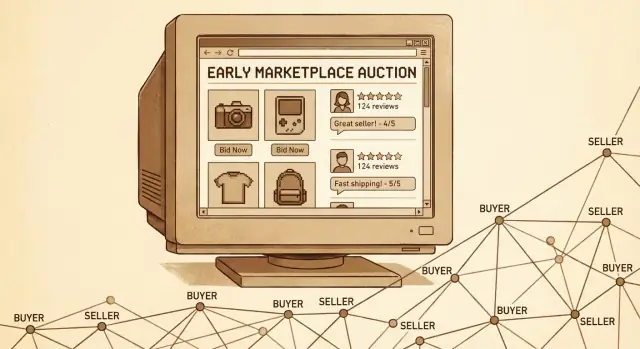

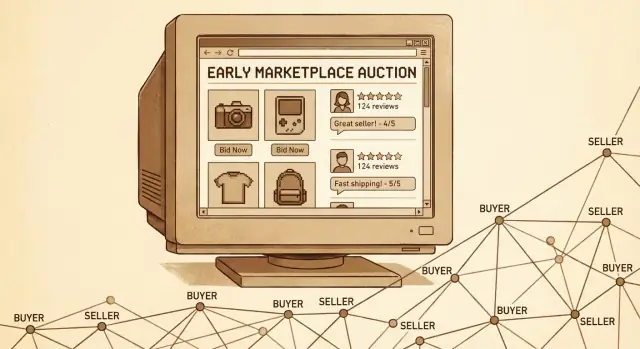

A two-sided marketplace is a business that brings together two groups who need each other—typically buyers and sellers—and makes it easier for them to transact. Instead of owning inventory, the marketplace runs the “meeting place” where supply and demand can find a match.

That sounds simple, but a working marketplace has to solve several hard problems at once.

Buyers don’t want to search forever, and sellers don’t want their listings buried. A marketplace earns its keep by organizing choice: search, categories, filters, recommendations, and clear product pages. Good discovery reduces effort for buyers and increases exposure for sellers—both sides feel the market is “alive.”

Marketplaces help answer a basic question: “What is this worth?” Sometimes that’s a fixed-price listing; sometimes it’s more dynamic (like negotiating, offers, or auctions). The key is that the platform provides signals—comparable listings, recent sales, condition notes, shipping costs—so people can decide with confidence.

Even when a buyer and seller agree, the work isn’t over. Payments, shipping labels, order tracking, dispute handling, and customer support are part of the product. The smoother the flow, the more often people come back.

A marketplace can grow without hiring in proportion to every sale. As more sellers join, selection improves; as more buyers arrive, sellers earn more—growth can feed on itself.

None of this works without liquidity (enough active buyers and sellers for matches to happen quickly) and trust (confidence that listings are real, payment is safe, and issues will be handled fairly). If either one is missing, users leave—and the “meeting place” empties out.

Liquidity is the quiet reason a marketplace feels worth returning to. In plain terms, liquidity is how quickly a listing finds the right buyer—not just whether something sells, but whether it sells soon enough that sellers stay motivated and buyers learn that searching is time well spent.

You don’t need a finance degree to measure it. A few simple indicators tell you if your marketplace is gaining momentum:

When these metrics improve together, the marketplace starts to feel “easy.” Sellers feel rewarded, and buyers feel like there’s always something relevant to find.

Liquidity is also where the classic marketplace dilemma lives: buyers won’t show up without selection, and sellers won’t list without buyers. This chicken-and-egg problem isn’t a one-time hurdle; it’s the core tension you manage as you grow.

If eBay had plenty of listings but few buyers, sellers would churn. If it had eager buyers but thin inventory, buyers would bounce. Liquidity is what converts one-time curiosity into habit.

People don’t experience “marketplace liquidity” as a metric—they experience it as search results that feel alive.

A buyer searches and instantly sees enough relevant options, across prices and conditions. A seller lists and receives views, watchers, offers, or bids quickly. Even small signals of activity reduce doubt and increase the odds that both sides come back.

When liquidity is high, the marketplace feels like a place where things happen. That feeling is what creates repeat use—and repeat use is what compounds.

Early eBay didn’t just “sell stuff online”—it solved a specific problem: many items had uncertain value because they were rare, used, collectible, or hard to compare. An auction is a matching mechanism for that uncertainty. Instead of the seller guessing a price (and being wrong), the market reveals what buyers are willing to pay.

When supply is scattered and demand is unpredictable—think vintage parts, niche collectibles, or one-off used goods—fixed pricing can be brittle. Set the price too high and the item sits. Set it too low and the seller leaves money on the table. Auctions reduce that risk by letting demand speak through bids, which is especially powerful for the long tail of weird, unique inventory.

Auctions also create built-in reasons to return. Every new bid is a signal: “someone else wants this.” That pulls in watchers, prompts counterbids, and extends attention over days. The result is price discovery plus repeat visits—people come back to check the current price, track competitors, and time their final bid.

Auctions optimize for “best price” more than speed. Buyers may enjoy the thrill, but they also face uncertainty, waiting, and the cognitive load of strategizing. Sellers trade immediacy for the possibility of a higher clearing price.

Fixed-price formats tend to win when products are comparable, replenishable, or time-sensitive (new goods, standardized SKUs, “need it now”). That’s why many marketplaces blend both: auctions for discovery and long-tail uniqueness, fixed price for convenience and fast conversion.

If liquidity is the engine of a marketplace, trust is the fuel. In peer-to-peer commerce, buyers aren’t just choosing a product—they’re choosing a stranger. That creates a trust problem that doesn’t exist in traditional retail.

A reputation system makes past behavior visible. On eBay (and many online marketplaces after it), that typically includes:

These aren’t “nice-to-have” profile features. They are a product in themselves: a standardized way to evaluate risk.

Without reputation, every listing raises uncomfortable questions: Is the item authentic? Is it in the condition described? Will it ship on time? Will the buyer claim a false “item not received” to get a refund? Will payment be reversed?

Marketplaces can’t personally vouch for each transaction, so they need a scalable substitute for face-to-face trust.

Public feedback turns uncertainty into a decision. A buyer may still take a chance—but they can price the risk: choose a highly rated seller, avoid accounts with thin history, or accept a lower price from a riskier seller.

That visibility also changes behavior. Sellers protect their ratings because future sales depend on them. Buyers feel safer clicking “Buy,” which increases transactions, which generates more feedback—making the next buyer even more confident.

Reputation doesn’t eliminate bad actors, but it narrows the space where they can thrive.

Marketplaces don’t win because they look better—they win because they feel safer. Trust raises the percentage of visitors who actually transact. That higher conversion means more successful listings, faster sales, and better prices. Those outcomes make the marketplace feel “alive,” which is another way of saying: liquidity improves.

When buyers believe an item will arrive as described, and sellers believe they’ll get paid, both sides take actions they would otherwise avoid: placing bids, buying without messaging back and forth, listing higher-value items, and shipping quickly. Each of those choices increases completed transactions, which increases selection and repeat visits.

More transactions generate more feedback, more dispute outcomes, and more observable behavior. That creates a richer reputation graph: not just star ratings, but patterns—who ships on time, who frequently refunds, which categories produce problems, and which signals predict fraud.

Over time, the platform can set clearer norms (how listings should be written, what “good condition” means, how returns work) and enforce them consistently.

This is where the moat forms. A new entrant can copy the UI and even match fees, but it can’t instantly copy years of trust history: buyer and seller reputations, category-specific benchmarks, enforcement precedents, and the shared expectations that reduce anxiety at checkout.

That compounding loop—trust → more transactions → better data and norms → more trust—doesn’t just grow. It hardens.

Network effects are the simplest story in marketplaces: more sellers create more choice and better prices, which attracts more buyers; more buyers create more demand, which attracts more sellers. That loop is real—but it’s not evenly distributed.

Most marketplaces don’t have one giant, platform-wide network effect. They have many smaller ones that can be strong or weak depending on where you look.

This is why eBay’s power historically showed up in specific niches: once a category became liquid, it stayed attractive even if other categories were average.

A strong network effect means each new participant measurably improves the experience for others (faster sales, better matches, better pricing). A weak one is mostly marketing noise: lots of users, but not enough relevance within a given category or location to change outcomes.

In many marketplaces, buyers and sellers multi-home—they list and shop on multiple platforms. That weakens moats because participants can “take the network with them.” If posting elsewhere is easy, your advantage has to be more than just size.

The practical defenses tend to be earned, not forced:

The goal is to make one platform feel like the best place to complete a transaction—not just to start browsing.

A reputation system only works when people believe it reflects real behavior. If buyers think ratings are inflated, or sellers think they’re easily weaponized, feedback stops guiding decisions—and the marketplace loses one of its strongest self-policing tools.

Credibility starts with friction and proof. Reviews should be hard to fake and tightly tied to real transactions. The best signals share two properties:

Even “simple” feedback systems fail in predictable ways:

A few mechanisms do most of the work:

No system stays fair without consistent enforcement. Clear policies, predictable penalties, and fast handling of edge cases teach users what “good behavior” means—and reassure everyone that the rules apply to both sides, not just whoever complains loudest.

A marketplace is a coordination system: buyers want low risk and fair prices, sellers want demand and predictable rules. Fees are one of the few levers the platform can use to align those incentives—if the platform charges for successful transactions, it has a reason to invest in the things that make successful transactions more likely.

The most defensible fee model isn’t “pay us to exist,” it’s “pay us when value is created.” When revenue is linked to completed sales, the platform is motivated to:

That alignment matters because Trust & Safety is not just a cost center. It’s a product feature that keeps good sellers selling and good buyers buying—exactly what drives marketplace liquidity.

Liquidity improves when listing and fulfillment are easier, faster, and more predictable. The platform can reinvest fee revenue into tools that help sellers create better listings and deliver reliably, such as:

These aren’t “nice-to-haves.” Every drop of friction that delays a listing, reduces listing quality, or creates shipping uncertainty reduces conversion—and fewer conversions means fewer future listings.

Trust requires clear rules and consistent enforcement: how disputes are handled, how suspicious activity is reviewed, and what happens when an item isn’t as expected. Good policies create a predictable environment where honest users feel protected.

But there’s a balancing act. Too much friction (excessive verification, confusing holds, slow dispute timelines) can choke liquidity by making it harder to buy and sell. Too little friction invites fraud, which quietly taxes every transaction through fear, refunds, and churn. The goal of Trust & Safety is not maximum control—it’s the minimum effective friction that keeps the flywheel spinning.

Early marketplaces fail for a simple reason: nobody shows up to an empty party. The temptation is to go broad—“everything for everyone”—but that usually dilutes the one thing you need first: a tight loop of buyers and sellers who can reliably find each other.

A focused niche gives you clearer inventory standards, more comparable pricing, and faster feedback cycles. Buyers learn what “good” looks like, sellers learn what moves, and you can tune trust and safety rules to a specific set of behaviors.

A general marketplace inherits every fraud pattern, dispute type, and quality expectation at once.

“Seeding” isn’t about manufacturing activity; it’s about ensuring real buyers see real selection on day one.

The trust rule here is simple: if you subsidize growth, don’t subsidize bad behavior. Discounts and onboarding help should be tied to fulfillment and customer satisfaction.

Demand growth that compounds tends to be boring but effective: SEO for specific queries, referrals that reward both sides, and retention mechanics like email alerts, saved searches, and back-in-stock notifications. These tools bring buyers back without pushing them into risky transactions.

Add new categories when one niche shows strong signals: consistent sell-through, fast time-to-first-sale, low dispute rates, and repeat purchasing. Expansion should feel like copying a proven playbook—not restarting the cold start problem in ten places at once.

A marketplace is defensible when it reliably answers three questions: Will people find what they want (liquidity)? Will they feel safe doing it (reputation)? Will the system get better as more people join (network effects)? eBay’s enduring strength came from compounding all three.

Liquidity is the “I can show up and succeed” feeling—buyers find selection fast, and sellers see demand without waiting.

Reputation turns trust into a product feature: credible profiles, verified outcomes, and consequences for bad behavior.

Network effects live where participation creates measurable improvement: more sellers increase selection; more buyers increase sell-through; more transactions improve ranking, pricing, and fraud detection.

Low repeat rate after a “successful” first transaction, thin or stale supply, high cancellation/dispute rates, and sellers that buyers avoid (or can’t distinguish from good ones) are all signals your flywheel isn’t spinning.

Map your unit economics and fee strategy (see /pricing), then audit your trust surface area—payments, messaging, fulfillment, disputes.

If you’re moving from strategy to execution, it can help to prototype the marketplace “machinery” early (listings, search, checkout, ratings, admin moderation flows) so you can test liquidity and trust assumptions with real users. Platforms like Koder.ai are useful here: you can build and iterate on a marketplace MVP via chat (web, backend, and even mobile), then export the source code when you’re ready to harden it—making it easier to run fast experiments without skipping Trust & Safety fundamentals.

For more tactical playbooks on liquidity and reputation design, browse /blog and compare your metrics to the checklist above.

eBay is a long-running example of a marketplace that stayed valuable as categories and competitors changed. For marketplace builders, it highlights three compounding advantages:

The key lesson: competitors can copy UI, but they can’t instantly copy accumulated trust history and dense, category-level liquidity.

Liquidity is the practical probability that a buyer finds what they want and a seller makes a sale quickly enough that both sides return. It’s less about total users and more about whether the marketplace feels “alive” in a specific category or geography.

If liquidity is low, even strong marketing can’t save the experience because users won’t get outcomes (sales for sellers, relevant selection for buyers).

Start with a few operational metrics that reflect real outcomes:

Track them by category and location, not just globally, because liquidity is often local.

Prioritize a tight loop over broad supply:

Avoid “fake activity.” It may boost top-line numbers briefly, but it erodes trust and increases disputes, which kills retention.

Auctions work best when price is uncertain and items are unique (collectibles, long-tail used goods). They help the market discover value without the seller guessing.

Fixed price tends to win when items are comparable or time-sensitive (standard SKUs, replenishable goods). Many marketplaces blend both:

A reputation system turns past behavior into decision-ready signals so users can transact with strangers. Practical ingredients include:

The goal isn’t perfection—it’s making risk legible enough that more people complete transactions.

Design for credibility by making feedback costly to fake and hard to weaponize:

Pair this with a dispute process that’s fast and consistent so users believe the system is fair.

Network effects are often category- or geo-specific. More users only helps if they increase relevant selection and successful matches where a buyer is actually searching.

Operationally, treat each category (or city) like its own market:

Multi-homing is when buyers/sellers use multiple platforms, which weakens “size” as a moat. You can’t prevent it sustainably by trapping users; you reduce it by being the best place to close the transaction:

Aim to be where outcomes are most predictable, not just where browsing starts.

Charging primarily on successful transactions aligns the platform with outcomes: fewer scams, smoother discovery, and better dispute handling all increase completed sales.

Use fee revenue to fund Trust & Safety as product work:

Balance matters: too much friction can reduce conversion, but too little invites fraud that quietly taxes every transaction through churn.