Dec 18, 2025·7 min

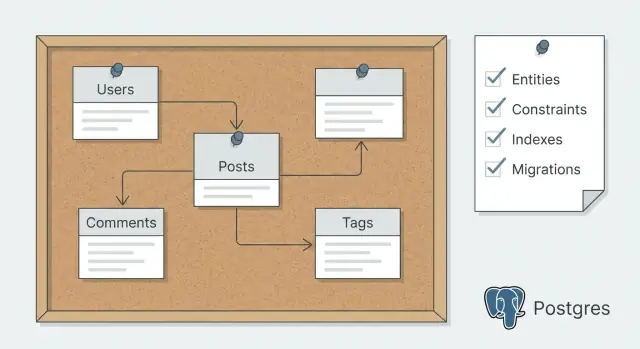

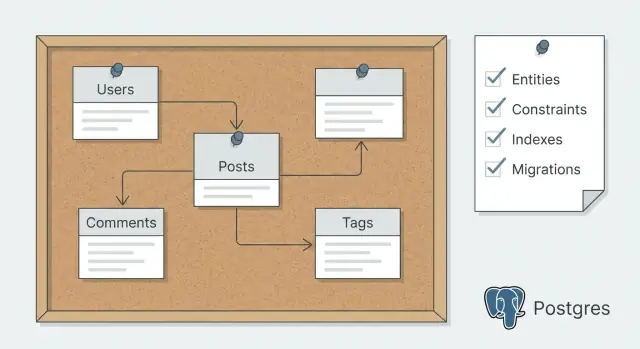

Postgres schema design planning mode: step-by-step approach

Postgres schema design planning mode helps you define entities, constraints, indexes, and migrations before code generation, cutting rewrites later.

Postgres schema design planning mode helps you define entities, constraints, indexes, and migrations before code generation, cutting rewrites later.

If you build endpoints and models before the database shape is clear, you usually end up rewriting the same features twice. The app works for a demo, then real data and real edge cases arrive and everything starts to feel brittle.

Most rewrites come from three predictable problems:

Each one forces changes that ripple through code, tests, and client apps.

Planning your Postgres schema means deciding the data contract first, then generating code that matches it. In practice, that looks like writing down entities, relationships, and the few queries that matter, then choosing constraints, indexes, and a migration approach before any tool scaffolds tables and CRUD.

This matters even more when you use a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai, where you can generate a lot of code quickly. Fast generation is great, but it’s far more reliable when the schema is settled. Your generated models and endpoints need fewer edits later.

Here’s what typically goes wrong when you skip planning:

A good schema plan is simple: a plain-language description of your entities, a draft of tables and columns, the key constraints and indexes, and a migration strategy that lets you change things safely as the product grows.

Schema planning works best when you begin with what the app must remember and what people must be able to do with that data. Write the goal in 2 to 3 plain sentences. If you can’t explain it simply, you’ll probably create extra tables you don’t need.

Next, focus on the actions that create or change data. These actions are the real source of your rows, and they reveal what must be validated. Think in verbs, not nouns.

For example, a booking app might need to create a booking, reschedule it, cancel it, refund it, and message the customer. Those verbs quickly suggest what must be stored (time slots, status changes, money amounts) before you ever name a table.

Capture your read paths too, because reads drive structure and indexing later. List the screens or reports people will actually use and how they slice the data: “My bookings” sorted by date and filtered by status, admin search by customer name or booking reference, daily revenue by location, and an audit view of who changed what and when.

Finally, note the non-functional needs that change schema choices, like audit history, soft deletes, multi-tenant separation, or privacy rules (for example, limiting who can see contact details).

If you plan to generate code after this, these notes become strong prompts. They spell out what’s required, what can change, and what must be searchable. If you’re using Koder.ai, writing this down before you generate anything makes Planning Mode much more effective because the platform is working from real requirements instead of guesses.

Before you touch tables, write a plain description of what your app stores. Start by listing the nouns you keep repeating: user, project, message, invoice, subscription, file, comment. Each noun is a candidate entity.

Then add one sentence per entity that answers: what is it, and why does it exist? For example: “A Project is a workspace a user creates to group work and invite others.” This prevents vague tables like data, items, or misc.

Ownership is the next big decision, and it affects almost every query you write. For each entity, decide:

Now decide how you’ll identify records. UUIDs are great when records can be created from many places (web, mobile, background jobs) or when you don’t want predictable IDs. Bigint IDs are smaller and faster. If you need a human-friendly identifier, keep it separate (for example, a short project_code that’s unique within an account) instead of forcing it to be the primary key.

Finally, write relationships in words before you diagram anything: a user has many projects, a project has many messages, and users can belong to many projects. Mark each link as required or optional, like “a message must belong to a project” vs “an invoice may belong to a project.” These sentences become your source of truth for code generation later.

Once the entities read clearly in plain language, turn each one into a table with columns that match real facts you need to store.

Start with names and types you can stick with. Pick consistent patterns: snake_case column names, the same type for the same idea, and predictable primary keys. For timestamps, prefer timestamptz so time zones don’t surprise you later. For money, use numeric(12,2) (or store cents as an integer) rather than floats.

For status fields, use either a Postgres enum or a text column with a CHECK constraint so allowed values are controlled.

Decide what’s required vs optional by translating rules into NOT NULL. If a value must exist for the row to make sense, make it required. If it’s truly unknown or not applicable, allow nulls.

A practical default set of columns to plan for:

id (uuid or bigint, pick one approach and stay consistent)created_at and updated_atdeleted_at only if you truly need soft deletes and restorecreated_by when you need a clear audit trail of who did whatMany-to-many relationships should almost always become join tables. For example, if multiple users can collaborate on an app, create app_members with app_id and user_id, then enforce uniqueness on the pair so duplicates can’t happen.

Think about history early. If you know you’ll need versioning, plan an immutable table such as app_snapshots, where each row is a saved version linked to apps by app_id and stamped with created_at.

Constraints are the guardrails of your schema. Decide which rules must be true no matter which service, script, or admin tool touches the database.

Start with identity and relationships. Every table needs a primary key, and any “belongs to” field should be a real foreign key, not just an integer you hope matches.

Then add uniqueness where duplicates would cause real harm, like two accounts with the same email or two line items with the same (order_id, product_id).

High-value constraints to plan early:

amount >= 0, status IN ('draft','paid','canceled'), or rating BETWEEN 1 AND 5.Cascade behavior is where planning saves you later. Ask what people actually expect. If a customer is deleted, their orders usually should not disappear. That points to restrict deletes and keep history. For dependent data like order line items, cascading from order to items can make sense because items have no meaning without the parent.

When you later generate models and endpoints, these constraints become clear requirements: what errors to handle, what fields are required, and what edge cases are impossible by design.

Indexes should answer one question: what needs to be fast for real users.

Start with the screens and API calls you expect to ship first. A list page that filters by status and sorts by newest has different needs than a detail page that loads related records.

Write down 5 to 10 query patterns in plain English before choosing any index. For example: “Show my invoices for the last 30 days, filter by paid/unpaid, sort by created_at,” or “Open a project and list its tasks by due_date.” This keeps index choices grounded in real usage.

A good first set of indexes often includes foreign key columns used for joins, common filter columns (like status, user_id, created_at), and one or two composite indexes for stable multi-filter queries, like (account_id, created_at) when you always filter by account_id and then sort by time.

Composite index order matters. Put the column you filter on most often (and that’s most selective) first. If you filter by tenant_id on every request, it often belongs at the front of many indexes.

Avoid indexing everything “just in case.” Every index adds work on INSERT and UPDATE, and that can hurt more than a slightly slower rare query.

Plan text search separately. If you only need simple “contains” matching, ILIKE might be enough at first. If search is core, plan for full-text search (tsvector) early so you don’t have to redesign later.

A schema isn’t “done” when you create the first tables. It changes every time you add a feature, fix a mistake, or learn more about your data. If you decide your migration strategy up front, you avoid painful rewrites after code generation.

Keep a simple rule: change the database in small steps, one feature at a time. Each migration should be easy to review and safe to run in every environment.

Most breakages come from renaming or removing columns, or changing types. Instead of doing everything in one shot, plan a safe path:

This takes more steps, but it’s faster in real life because it reduces outages and emergency patches.

Seed data is part of migrations too. Decide which reference tables are “always there” (roles, statuses, countries, plan types) and make them predictable. Put inserts and updates for these tables into dedicated migrations so every developer and every deploy gets the same results.

Set expectations early:

Rollbacks are not always a perfect “down migration.” Sometimes the best rollback is a backup restore. If you’re using Koder.ai, it’s also worth deciding when to rely on snapshots and rollback for quick recovery, especially before risky changes.

Imagine a small SaaS app where people join teams, create projects, and track tasks.

Start by listing the entities and only the fields you need on day one:

Relationships are straightforward: a team has many projects, a project has many tasks, and users join teams through team_members. Tasks belong to a project and may be assigned to a user.

Now add a few constraints that prevent bugs you typically find too late:

Indexes should match real screens. For example, if the task list filters by project and state and sorts by newest, plan an index like tasks (project_id, state, created_at DESC). If “My tasks” is a key view, an index like tasks (assignee_user_id, state, due_date) can help.

For migrations, keep the first set safe and boring: create tables, primary keys, foreign keys, and the core unique constraints. A good follow-up change is something you add after usage proves it, like introducing soft delete (deleted_at) on tasks and adjusting “active tasks” indexes to ignore deleted rows.

Most rewrites happen because the first schema is missing rules and real usage details. A good planning pass isn’t about perfect diagrams. It’s about spotting traps early.

A common error is keeping important rules only in application code. If a value must be unique, present, or within a range, the database should enforce it too. Otherwise a background job, a new endpoint, or a manual import can bypass your logic.

Another frequent miss is treating indexes as a later problem. Adding them after launch often turns into guesswork, and you can end up indexing the wrong thing while the real slow query is a join or a filter on a status field.

Many-to-many tables are also a source of quiet bugs. If your join table doesn’t prevent duplicates, you can store the same relationship twice and spend hours debugging “why does this user have two roles?”

It’s also easy to create tables first and then realize you need audit logs, soft deletes, or event history. Those additions ripple into endpoints and reports.

Finally, JSON columns are tempting for “flexible” data, but they remove checks and make indexing harder. JSON is fine for truly variable payloads, not core business fields.

Before you generate code, run this quick fix list:

Pause here and make sure the plan is complete enough to generate code without chasing surprises. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s catching the gaps that cause rewrites later: missing relationships, unclear rules, and indexes that don’t match how the app is actually used.

Use this as a fast pre-flight check:

amount >= 0 or allowed statuses).A quick sanity test: pretend a teammate joins tomorrow. Could they build the first endpoints without asking “can this be null?” or “what happens on delete?” every hour?

Once the plan reads clearly and the main flows make sense on paper, turn it into something executable: a real schema plus migrations.

Start with an initial migration that creates tables, types (if you use enums), and the must-have constraints. Keep the first pass small but correct. Load a little seed data and run the queries your app will actually need. If a flow feels awkward, fix the schema while the migration history is still short.

Generate models and endpoints only after you can test a few end-to-end actions with the schema in place (create, update, list, delete, plus one real business action). Code generation is fastest when tables, keys, and naming are stable enough that you aren’t renaming everything the next day.

A practical loop that keeps rewrites low:

Decide early what you validate in the database vs the API layer. Put permanent rules in the database (foreign keys, unique constraints, check constraints). Keep soft rules in the API (feature flags, temporary limits, and complex cross-table logic that changes often).

If you use Koder.ai, a sensible approach is to agree on entities and migrations in Planning Mode first, then generate your Go plus PostgreSQL backend. When a change goes sideways, snapshots and rollback can help you get back to a known-good version quickly while you adjust the schema plan.

Plan the schema first. It sets a stable data contract (tables, keys, constraints) so generated models and endpoints don’t need constant renames and rewrites later.

In practice: write your entities, relationships, and top queries, then lock in constraints, indexes, and migrations before you generate code.

Write 2–3 sentences describing what the app must remember and what users must be able to do.

Then list:

This gives you enough clarity to design tables without overbuilding.

Start by listing the nouns you keep repeating (user, project, invoice, task). For each one, add one sentence: what it is and why it exists.

If you can’t describe it clearly, you’ll likely end up with vague tables like items or misc and regret it later.

Default to a single consistent ID strategy across your schema.

If you need a human-friendly identifier, add a separate unique column (like project_code) instead of using it as the primary key.

Decide it per relationship based on what users expect and what must be preserved.

Common defaults:

RESTRICT/NO ACTION when deleting a parent would erase important records (like customers → orders)CASCADE when child rows have no meaning without the parent (like order → line items)Make this decision early because it affects API behavior and edge cases.

Put permanent rules in the database so every writer (API, scripts, imports, admin tools) is forced to behave.

Prioritize:

Start from real query patterns, not guesses.

Write 5–10 plain-English queries (filters + sort), then index for those:

status, user_id, created_atCreate a join table with two foreign keys and a composite unique constraint.

Example pattern:

team_members(team_id, user_id, role, joined_at)UNIQUE (team_id, user_id) to prevent duplicatesThis prevents subtle bugs like “why does this user appear twice?” and keeps your queries clean.

Default to:

timestamptz for timestamps (fewer time zone surprises)numeric(12,2) or integer cents for money (avoid floats)CHECK constraintsKeep types consistent across tables (same type for the same concept) so joins and validations stay predictable.

Use small, reviewable migrations and avoid breaking changes in one step.

A safe path:

Also decide upfront how you’ll handle seed/reference data so every environment matches.

PRIMARY KEY on every tableFOREIGN KEY for every “belongs to” columnUNIQUE where duplicates cause real harm (email, (team_id, user_id) in join tables)CHECK for simple rules (non-negative amounts, allowed statuses)NOT NULL for fields required for the row to make sense(account_id, created_at)Avoid indexing everything; each index slows inserts and updates.