Sep 02, 2025·8 min

Protobuf vs JSON for APIs: Speed, Size, and Compatibility

Compare Protobuf and JSON for APIs: payload size, speed, readability, tooling, versioning, and when each format fits best in real products.

Compare Protobuf and JSON for APIs: payload size, speed, readability, tooling, versioning, and when each format fits best in real products.

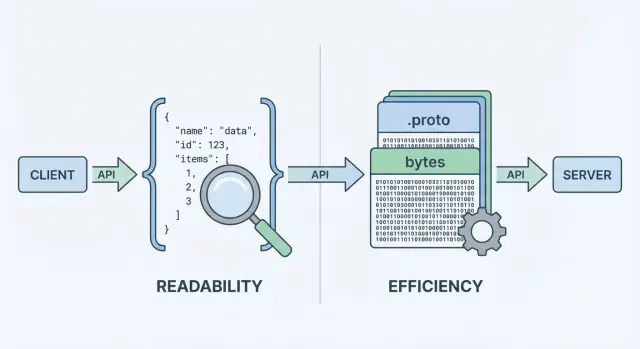

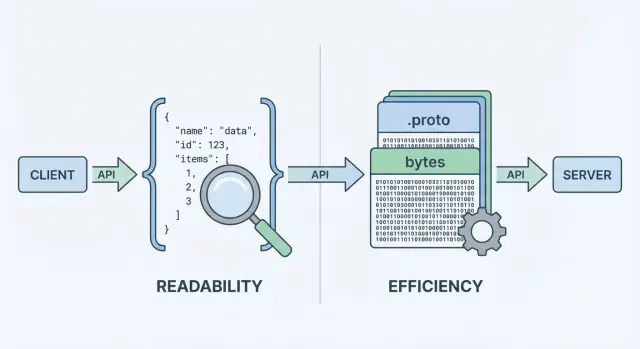

When your API sends or receives data, it needs a data format—a standardized way to represent information in the request and response bodies. That format is then serialized (turned into bytes) for transport over the network, and deserialized back into usable objects on the client and server.

Two of the most common choices are JSON and Protocol Buffers (Protobuf). They can represent the same business data (users, orders, timestamps, lists of items), but they make different trade-offs around performance, payload size, and developer workflow.

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is a text-based format built from simple structures like objects and arrays. It’s popular for REST APIs because it’s easy to read, easy to log, and easy to inspect with tools like curl and browser DevTools.

A big reason JSON is everywhere: most languages have excellent support, and you can visually inspect a response and understand it immediately.

Protobuf is a binary serialization format created by Google. Instead of sending text, it sends a compact binary representation defined by a schema (a .proto file). The schema describes the fields, their types, and their numeric tags.

Because it’s binary and schema-driven, Protobuf usually produces smaller payloads and can be faster to parse—which matters when you have high request volumes, mobile networks, or latency-sensitive services (commonly in gRPC setups, but not limited to gRPC).

It’s important to separate what you’re sending from how it’s encoded. A “user” with an id, name, and email can be modeled in both JSON and Protobuf. The difference is the cost you pay in:

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. For many public-facing APIs, JSON remains the default because it’s accessible and flexible. For internal service-to-service communication, performance-sensitive systems, or strict contracts, Protobuf can be a better fit. The goal of this guide is to help you choose based on constraints—not ideology.

When an API returns data, it can’t send “objects” directly over the network. It has to turn them into a stream of bytes first. That conversion is serialization—think of it as packing data into a shippable form. On the other side, the client does the reverse (deserialization), unpacking the bytes back into usable data structures.

A typical request/response flow looks like this:

That “encoding step” is where the format choice matters. JSON encoding produces readable text like {\"id\":123,\"name\":\"Ava\"}. Protobuf encoding produces compact binary bytes that aren’t meaningful to humans without tooling.

Because every response must be packed and unpacked, the format influences:

Your API style often nudges the decision:

curl, and simple to log and inspect.You can use JSON with gRPC (via transcoding) or use Protobuf over plain HTTP, but the default ergonomics of your stack—frameworks, gateways, client libraries, and debugging habits—will often decide what feels easiest to run day-to-day.

When people compare protobuf vs json, they usually start with two metrics: how big the payload is and how long it takes to encode/decode. The headline is simple: JSON is text and tends to be verbose; Protobuf is binary and tends to be compact.

JSON repeats field names and uses text representations for numbers, booleans, and structure, so it often sends more bytes over the wire. Protobuf replaces field names with numeric tags and packs values efficiently, which commonly leads to noticeably smaller payloads—especially for large objects, repeated fields, and deeply nested data.

That said, compression can narrow the gap. With gzip or brotli, JSON’s repeated keys compress very well, so “JSON vs Protobuf size” differences may shrink in real deployments. Protobuf can also be compressed, but the relative win is often smaller.

JSON parsers must tokenize and validate text, convert strings into numbers, and deal with edge cases (escaping, whitespace, unicode). Protobuf decoding is more direct: read tag → read typed value. In many services, Protobuf reduces CPU time and garbage creation, which can improve tail latency under load.

On mobile networks or high-latency links, fewer bytes typically means faster transfers and less radio time (which can also help battery). But if your responses are already small, handshake overhead, TLS, and server processing may dominate—making the format choice less visible.

Measure with your real payloads:

This turns “API serialization” debates into data you can trust for your API.

Developer experience is where JSON often wins by default. You can inspect a JSON request or response almost anywhere: in browser DevTools, curl output, Postman, reverse proxies, and plain-text logs. When something breaks, “what did we actually send?” is usually one copy/paste away.

Protobuf is different: it’s compact and strict, but not human-readable. If you log raw Protobuf bytes, you’ll see base64 blobs or unreadable binary. To understand the payload, you need the right .proto schema and a decoder (for example, protoc, language-specific tooling, or your service’s generated types).

With JSON, reproducing issues is straightforward: grab a logged payload, redact secrets, replay it with curl, and you’re close to a minimal test case.

With Protobuf, you’ll typically debug by:

That extra step is manageable—but only if the team has a repeatable workflow.

Structured logging helps both formats. Log request IDs, method names, user/account identifiers, and key fields rather than whole bodies.

For Protobuf specifically:

.proto did we use?” confusion.For JSON, consider logging canonicalized JSON (stable key ordering) to make diffs and incident timelines easier to read.

APIs don’t just move data—they move meaning. The biggest difference between JSON and Protobuf is how clearly that meaning is defined and enforced.

JSON is “schema-less” by default: you can send any object with any fields, and many clients will accept it as long as it looks reasonable.

That flexibility is convenient early on, but it can also hide mistakes. Common pitfalls include:

userId in one response, user_id in another, or missing fields depending on the code path.You can add a JSON Schema or OpenAPI spec, but JSON itself doesn’t require consumers to follow it.

Protobuf requires a schema defined in a .proto file. A schema is a shared contract that states:

That contract helps prevent accidental changes—like turning an integer into a string—because the generated code expects specific types.

With Protobuf, numbers stay numbers, enums are bounded to known values, and timestamps are typically modeled using well-known types (instead of ad hoc string formats). “Not set” is also clearer: in proto3, absence is distinct from default values when you use optional fields or wrapper types.

If your API depends on precise types and predictable parsing across teams and languages, Protobuf provides guardrails that JSON usually relies on conventions to achieve.

APIs evolve: you add fields, tweak behavior, and retire old parts. The goal is to change the contract without surprising consumers.

A good evolution strategy aims for both, but backward compatibility is usually the minimum bar.

In Protobuf, each field has a number (e.g., email = 3). That number—not the field name—is what goes on the wire. Names are mainly for humans and generated code.

Because of that:

Safe changes (usually)

Best practice: use reserved for old numbers/names and keep a changelog.

JSON doesn’t have a built-in schema, so compatibility depends on your patterns:

Document deprecations early: when a field is deprecated, how long it will be supported, and what replaces it. Publish a simple versioning policy (e.g., “additive changes are non-breaking; removals require a new major version”) and stick to it.

Choosing between JSON and Protobuf often comes down to where your API needs to run—and what your team wants to maintain.

JSON is effectively universal: every browser and backend runtime can parse it without extra dependencies. In a web app, fetch() + JSON.parse() is the happy path, and proxies, API gateways, and observability tools tend to “understand” JSON out of the box.

Protobuf can run in the browser too, but it’s not a zero-cost default. You’ll typically add a Protobuf library (or generated JS/TS code), manage bundling size, and decide whether you’re sending Protobuf over HTTP endpoints that your browser tooling can easily inspect.

On iOS/Android and in backend languages (Go, Java, Kotlin, C#, Python, etc.), Protobuf support is mature. The big difference is that Protobuf assumes you’ll use libraries per platform and usually generate code from .proto files.

Code generation brings real benefits:

It also adds costs:

.proto packages, version pinning)Protobuf is closely associated with gRPC, which gives you a complete tooling story: service definitions, client stubs, streaming, and interceptors. If you’re considering gRPC, Protobuf is the natural fit.

If you’re building a traditional JSON REST API, JSON’s tooling ecosystem (browser DevTools, curl-friendly debugging, generic gateways) remains simpler—especially for public APIs and quick integrations.

If you’re still exploring the API surface, it can help to prototype quickly in both styles before you standardize. For example, teams using Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform) often spin up a JSON REST API for broad compatibility and an internal gRPC/Protobuf service for efficiency, then benchmark real payloads before choosing what becomes “default.” Because Koder.ai can generate full-stack apps (React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, Flutter for mobile) and supports planning mode plus snapshots/rollback, it’s practical to iterate on contracts without turning format decisions into a long-lived refactor.

Choosing between JSON and Protobuf isn’t only about payload size or speed. It also affects how well your API fits with caching layers, gateways, and the tools your team relies on during incidents.

Most HTTP caching infrastructure (browser caches, reverse proxies, CDNs) is optimized around HTTP semantics, not a particular body format. A CDN can cache any bytes as long as the response is cacheable.

That said, many teams expect HTTP/JSON at the edge because it’s easy to inspect and troubleshoot. With Protobuf, caching still works, but you’ll want to be deliberate about:

Vary)Cache-Control, ETag, Last-Modified)If you support both JSON and Protobuf, use content negotiation:

Accept: application/json or Accept: application/x-protobufContent-TypeMake sure caches understand this by setting Vary: Accept. Otherwise, a cache might store a JSON response and serve it to a Protobuf client (or the other way around).

API gateways, WAFs, request/response transformers, and observability tools often assume JSON bodies for:

Binary Protobuf can limit those features unless your tooling is Protobuf-aware (or you add decoding steps).

A common pattern is JSON at the edges, Protobuf inside:

This keeps external integrations simple while still capturing Protobuf’s performance benefits where you control both client and server.

Choosing JSON or Protobuf changes how data is encoded and parsed—but it doesn’t replace core security requirements like authentication, encryption, authorization, and server-side validation. A fast serializer won’t save an API that accepts untrusted input without limits.

It can be tempting to treat Protobuf as “safer” because it’s binary and less readable. That’s not a security strategy. Attackers don’t need your payloads to be human-readable—they just need your endpoint. If the API leaks sensitive fields, accepts invalid states, or has weak auth, switching formats won’t fix it.

Encrypt transport (TLS), enforce authz checks, validate inputs, and log securely regardless of whether you use a JSON REST API or grpc protobuf.

Both formats share common risks:

To keep APIs dependable under load and abuse, apply the same guardrails to both formats:

The bottom line: “binary vs text format” mainly affects performance and ergonomics. Security and reliability come from consistent limits, up-to-date dependencies, and explicit validation—no matter which serializer you choose.

Picking between JSON and Protobuf is less about which one is “better” and more about what your API needs to optimize for: human friendliness and reach, or efficiency and strict contracts.

JSON is usually the safest default when you need broad compatibility and easy troubleshooting.

Typical scenarios:

Protobuf tends to win when performance and consistency matter more than human readability.

Typical scenarios:

Use these questions to quickly narrow the choice:

You can turn the following into a table in your doc:

If you’re still torn, the “JSON at the edge, Protobuf inside” approach is often a pragmatic compromise.

Migrating formats is less about rewriting everything and more about reducing risk for consumers. The safest moves keep the API usable throughout the transition and make it easy to roll back.

Pick a low-risk surface area—often an internal service-to-service call or a single read-only endpoint. This lets you validate the Protobuf schema, generated clients, and observability changes without turning the entire API into a “big bang” project.

A practical first step is adding a Protobuf representation for an existing resource while keeping the JSON shape unchanged. You’ll learn quickly where your data model is ambiguous (null vs missing, numbers vs strings, date formats) and can resolve it in the schema.

For external APIs, dual support is usually the smoothest path:

Content-Type and Accept headers./v2/...) only if negotiation is hard with your tooling.During this period, ensure both formats are produced from the same source-of-truth model to avoid subtle drift.

Plan for:

Publish .proto files, field comments, and concrete request/response examples (JSON and Protobuf) so consumers can verify they’re interpreting the data correctly. A short “migration guide” and changelog reduces support load and shortens adoption time.

Choosing between JSON and Protobuf is often less about ideology and more about the reality of your traffic, clients, and operational constraints. The most reliable path is to measure, document decisions, and keep your API changes boring.

Run a small experiment on representative endpoints.

Track:

Do this in staging with production-like data, then validate in production on a small slice of traffic.

Whether you use JSON Schema/OpenAPI or .proto files:

Even if you choose Protobuf for performance, keep your docs friendly:

If you maintain docs or SDK guides, link them clearly (for example: /docs and /blog). If pricing or usage limits affect format choices, make that visible too (/pricing).

JSON is a text-based format that’s easy to read, log, and test with common tools. Protobuf is a compact binary format defined by a .proto schema, often yielding smaller payloads and faster parsing.

Pick based on constraints: reach and debuggability (JSON) vs efficiency and strict contracts (Protobuf).

APIs send bytes, not in-memory objects. Serialization encodes your server objects into a payload (JSON text or Protobuf binary) for transport; deserialization decodes those bytes back into client/server objects.

Your format choice affects bandwidth, latency, and CPU spent encoding/decoding.

Often yes, especially with large or nested objects and repeated fields, because Protobuf uses numeric tags and efficient binary encoding.

However, if you enable gzip/brotli, JSON’s repeated keys compress well, so the real-world size gap can shrink. Measure both raw and compressed sizes.

It can. JSON parsing requires tokenizing text, handling escaping/unicode, and converting strings to numbers. Protobuf decoding is more direct (tag → typed value), which often reduces CPU time and allocations.

That said, if payloads are tiny, overall latency may be dominated by TLS, network RTT, and application work rather than serialization.

It’s harder by default. JSON is human-readable and easy to inspect in DevTools, logs, curl, and Postman. Protobuf payloads are binary, so you typically need the matching .proto schema and decoding tooling.

A common workflow improvement is logging a decoded, redacted debug view (often JSON) alongside request IDs and key fields.

JSON is flexible and often “schema-less” unless you enforce JSON Schema/OpenAPI. That flexibility can lead to inconsistent fields, “stringly-typed” values, and ambiguous null semantics.

Protobuf enforces types via a .proto contract, generates strongly typed code, and makes evolvable contracts clearer—especially when multiple teams and languages are involved.

Protobuf compatibility is driven by field numbers (tags). Safe changes are usually additive (new optional fields with new numbers). Breaking changes include reusing field numbers or changing types incompatibly.

For Protobuf, reserve removed field numbers/names (reserved) and keep a changelog. For JSON, prefer additive fields, keep types stable, and treat unknown fields as ignorable.

Yes. Use HTTP content negotiation:

Accept: application/json or Accept: application/x-protobufContent-TypeVary: Accept so caches don’t mix formatsIf tooling makes negotiation difficult, a separate endpoint/version can be a temporary migration tactic.

It depends on your environment:

Consider the maintenance cost of codegen and shared schema versioning when choosing Protobuf.

Treat both as untrusted input. Format choice isn’t a security layer.

Practical guardrails for both:

Keep parsers/libraries updated to reduce exposure to parser vulnerabilities.

\"42\"\"true\"\"2025-12-23\"null might mean “unknown,” “not set,” or “intentionally empty,” and different clients may treat it differently.Risky changes (often breaking)