Oct 21, 2025·7 min

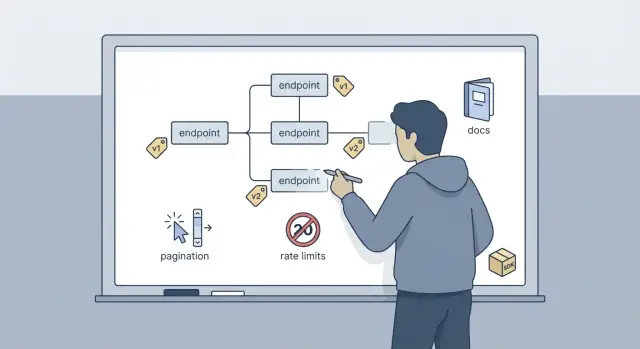

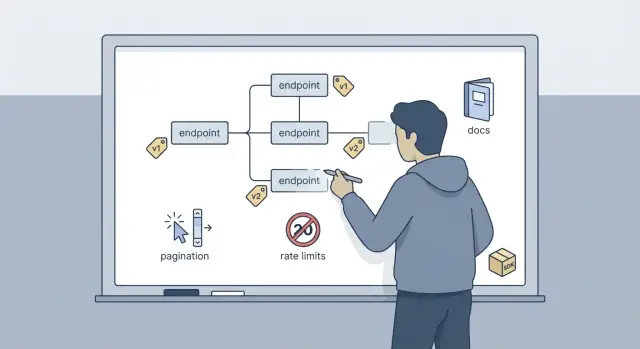

Public API design for first-time SaaS builders: basics

Public API design made practical for first-time SaaS builders: choose versioning, pagination, rate limits, docs, and a small SDK you can ship fast.

Public API design made practical for first-time SaaS builders: choose versioning, pagination, rate limits, docs, and a small SDK you can ship fast.

A public API isn't just an endpoint your app exposes. It's a promise to people outside your team that the contract will keep working, even as you change the product.

The hard part isn't writing v1. It's keeping it stable while you fix bugs, add features, and learn what customers actually need.

Early choices show up later as support tickets. If responses change shape without warning, if naming is inconsistent, or if clients can't tell whether a request succeeded, you create friction. That friction turns into mistrust, and mistrust makes people stop building on you.

Speed matters too. Most first-time SaaS builders need to ship something useful fast, then improve it. The tradeoff is simple: the faster you ship without rules, the more time you'll spend undoing those decisions when real users arrive.

Good enough for v1 usually means a small set of endpoints that map to real user actions, consistent naming and response shapes, a clear change strategy (even if it's just v1), predictable pagination and sane rate limits, and docs that show exactly what to send and what you'll get back.

A concrete example: imagine a customer builds an integration that creates invoices nightly. If you later rename a field, change date formats, or silently start returning partial results, their job fails at 2 a.m. They'll blame your API, not their code.

If you build with a chat-driven tool like Koder.ai, it's tempting to generate many endpoints quickly. That's fine, but keep the public surface small. You can keep internal endpoints private while you learn what should be part of the long-term contract.

Good public API design starts by choosing a small set of nouns (resources) that match how customers talk about your product. Keep resource names stable even if your internal database changes. When you add features, prefer adding fields or new endpoints over renaming core resources.

A practical starting set for many SaaS products looks like: users, organizations, projects, and events. If you can't explain a resource in one sentence, it's probably not ready to be public.

Keep HTTP usage boring and predictable:

Auth doesn't need to be fancy on day one. If your API is mainly server to server (customers calling from their backend), API keys are often enough. If customers need to act as individual end users, or you expect third-party integrations where users grant access, OAuth is usually a better fit. Write the decision in plain language: who is the caller, and whose data are they allowed to touch?

Set expectations early. Be explicit about what's supported vs best effort. For example: list endpoints are stable and backwards-compatible, but search filters may expand and aren't guaranteed to be exhaustive. This reduces support tickets and keeps you free to improve.

If you're building on a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai, treat the API as a product contract: keep the contract small first, then grow it based on real usage, not guesses.

Versioning is mostly about expectations. Clients want to know: will my integration break next week? You want room to improve things without fear.

Header-based versioning can look clean, but it's easy to hide from logs, caches, and support screenshots. URL versioning is usually the simplest choice: /v1/.... When a customer sends you a failing request, you can see the version immediately. It also makes it easy to run v1 and v2 side by side.

A change is breaking if a well-behaved client could stop working without changing their code. Common examples:

customer_id to customerId)A safe change is one that old clients can ignore. Adding a new optional field is usually safe. For instance, adding plan_name to a GET /v1/subscriptions response won't break clients that only read status.

A practical rule: don't remove or repurpose fields inside the same major version. Add new fields, keep the old ones, and retire them only when you're ready to deprecate the entire version.

Keep it simple: announce deprecations early, return a clear warning message in responses, and set an end date. For a first API, a 90-day window is often realistic. During that time, keep v1 working, publish a short migration note, and make sure support can point to one sentence: v1 works until this date; here's what changed in v2.

If you build on a platform like Koder.ai, treat API versions like snapshots: ship improvements in a new version, keep the old one stable, and only cut it off after you've given customers time to move.

Pagination is where trust is won or lost. If results jump around between requests, people stop trusting your API.

Use page/limit when the data set is small, the query is simple, and users often want page 3 of 20. Use cursor-based pagination when lists can grow large, new items arrive often, or the user can sort and filter a lot. Cursor-based pagination keeps the sequence stable even when new records are added.

A few rules keep pagination reliable:

Totals are tricky. A total_count can be expensive on big tables, especially with filters. If you can provide it cheaply, include it. If you can't, omit it or make it optional via a query flag.

Here are simple request/response shapes.

// Page/limit

GET /v1/invoices?page=2&limit=25&sort=created_at_desc

{

"items": [{"id":"inv_1"},{"id":"inv_2"}],

"page": 2,

"limit": 25,

"total_count": 142

}

// Cursor-based

GET /v1/invoices?limit=25&cursor=eyJjcmVhdGVkX2F0IjoiMjAyNi0wMS0wOVQxMDozMDowMFoiLCJpZCI6Imludl8xMDAifQ==

{

"items": [{"id":"inv_101"},{"id":"inv_102"}],

"next_cursor": "eyJjcmVhdGVkX2F0IjoiMjAyNi0wMS0wOVQxMDoyNTowMFoiLCJpZCI6Imludl8xMjUifQ=="

}

Rate limits are less about being strict and more about staying online. They protect your app from traffic spikes, your database from expensive queries done too often, and your wallet from surprise infrastructure bills. A limit is also a contract: clients know what normal usage looks like.

Start simple and tune later. Choose something that covers typical usage with room for short bursts, then watch real traffic. If you have no data yet, a safe default is a per-API-key limit like 60 requests per minute plus a small burst allowance. If one endpoint is much heavier (like search or exports), give it a stricter limit or a separate cost rule instead of punishing every request.

When you enforce limits, make it easy for clients to do the right thing. Return a 429 Too Many Requests response and include a few standard headers:

X-RateLimit-Limit: the max allowed in the windowX-RateLimit-Remaining: how many are leftX-RateLimit-Reset: when the window resets (timestamp or seconds)Retry-After: how long to wait before retryingClients should treat 429 as a normal condition, not an error to fight. A polite retry pattern keeps both sides happy:

Retry-After when it's presentExample: if a customer runs a nightly sync that hits your API hard, their job can spread requests across a minute and automatically slow down on 429s instead of failing the whole run.

If your API errors are hard to read, support tickets pile up fast. Pick one error shape and stick to it everywhere, including 500s. A simple standard is: code, message, details, and a request_id the user can paste into a support chat.

Here is a small, predictable format:

{

"error": {

"code": "validation_error",

"message": "Some fields are invalid.",

"details": {

"fields": [

{"name": "email", "issue": "must be a valid email"},

{"name": "plan", "issue": "must be one of: free, pro, business"}

]

},

"request_id": "req_01HT..."

}

}

Use HTTP status codes the same way every time: 400 for bad input, 401 when auth is missing or invalid, 403 when the user is authenticated but not allowed, 404 when a resource is not found, 409 for conflicts (like a duplicate unique value or wrong state), 429 for rate limits, and 500 for server errors. Consistency beats cleverness.

Make validation errors easy to fix. Field-level hints should point to the exact parameter name your docs use, not an internal database column. If there's a format requirement (date, currency, enum), say what you accept and show an example.

Retries are where many APIs accidentally create duplicate data. For important POST actions (payments, invoice creation, sending emails), support idempotency keys so clients can safely retry.

Idempotency-Key header on selected POST endpoints.That one header prevents a lot of painful edge cases when networks are flaky or clients hit timeouts.

Imagine you run a simple SaaS with three main objects: projects, users, and invoices. A project has many users, and each project gets monthly invoices. Clients want to sync invoices into their accounting tool and show basic billing inside their own app.

A clean v1 might look like this:

GET /v1/projects/{project_id}

GET /v1/projects/{project_id}/invoices

POST /v1/projects/{project_id}/invoices

Now a breaking change happens. In v1, you store invoice amounts as an integer in cents: amount_cents: 1299. Later, you need multi-currency and decimals, so you want amount: "12.99" and currency: "USD". If you overwrite the old field, every existing integration breaks. Versioning avoids the panic: keep v1 stable, ship /v2/... with the new fields, and support both until clients migrate.

For listing invoices, use a predictable pagination shape. For example:

GET /v1/projects/p_123/invoices?limit=50&cursor=eyJpZCI6Imludl85OTkifQ==

200 OK

{

"data": [ {"id":"inv_1001"}, {"id":"inv_1000"} ],

"next_cursor": "eyJpZCI6Imludl8xMDAwIn0="

}

One day a customer imports invoices in a loop and hits your rate limit. Instead of random failures, they get a clear response:

429 Too Many RequestsRetry-After: 20{ "error": { "code": "rate_limited" } }On their side, the client can pause for 20 seconds, then continue from the same cursor without re-downloading everything or creating duplicate invoices.

A v1 launch goes better when you treat it like a small product release, not a pile of endpoints. The goal is simple: people can build on it, and you can keep improving it without surprises.

Start by writing one page that explains what your API is for and what it is not. Keep the surface area small enough that you can explain it out loud in a minute.

Use this sequence and don't move on until each step is good enough:

If you build with a code-generating workflow (for example, using Koder.ai to scaffold endpoints and responses), still do the fake-client test. Generated code can look correct while still being awkward to use.

The payoff is fewer support emails, fewer hotfix releases, and a v1 you can actually maintain.

A first SDK isn't a second product. Think of it as a thin, friendly wrapper around your HTTP API. It should make the common calls easy, but it shouldn't hide how the API works. If someone needs a feature you haven't wrapped yet, they should still be able to drop down to raw requests.

Pick one language to start, based on what your customers actually use. For many B2B SaaS APIs that's often JavaScript/TypeScript or Python. Shipping one solid SDK beats shipping three half-finished ones.

A good starter set is:

You can build this by hand or generate it from an OpenAPI spec. Generation is great when your spec is accurate and you want consistent typing, but it often produces a lot of code. Early on, a hand-written minimal client plus an OpenAPI file for docs is usually enough. You can switch to generated clients later without breaking users, as long as the public SDK interface stays stable.

Your API version should follow your compatibility rules. Your SDK version should follow packaging rules.

If you add new optional parameters or new endpoints, that's usually a minor SDK bump. Reserve major SDK releases for breaking changes in the SDK itself (renamed methods, changed defaults), even if the API stayed the same. That separation keeps upgrades calm and support tickets low.

Most API support tickets aren't about bugs. They're about surprises. Public API design is mostly about being boring and predictable so client code keeps working month after month.

The fastest way to lose trust is changing responses without telling anyone. If you rename a field, change a type, or start returning null where you used to return a value, you'll break clients in ways that are hard for them to diagnose. If you truly must change behavior, version it, or add a new field and keep the old one for a while with a clear sunset plan.

Pagination is another repeat offender. Problems show up when one endpoint uses page/pageSize, another uses offset/limit, and a third uses cursors, all with different defaults. Pick one pattern for v1 and stick to it everywhere. Keep sorting stable too, so next page doesn't skip or repeat items when new records arrive.

Errors create a lot of back-and-forth when they're inconsistent. A common failure mode is one service returning { "error":"..." } and another returning { "message":"..." }, with different HTTP status codes for the same issue. Clients then build messy, endpoint-specific handlers.

Here are five mistakes that generate the longest email threads:

A simple habit helps: every response should include a request_id, and every 429 should explain when to retry.

Before you publish anything, do a final pass focused on consistency. Most support tickets happen because small details don't match across endpoints, docs, and examples.

Quick checks that catch the most issues:

After launch, watch what people actually hit, not what you hoped they'd use. A small dashboard and a weekly review is enough early on.

Monitor these signals first:

Collect feedback without rewriting everything. Add a short report an issue path in your docs, and tag each report with the endpoint, request id, and client version. When you fix something, prefer additive changes: new fields, new optional params, or a new endpoint, instead of breaking existing behavior.

Next steps: write a one-page API spec with your resources, versioning plan, pagination rules, and error format. Then produce docs and a tiny starter SDK that covers authentication plus 2 to 3 core endpoints. If you want to move faster, you can draft the spec, docs, and a starter SDK from a chat-based plan using tools like Koder.ai (its planning mode is a handy way to map endpoints and examples before you generate code).

Start with 5–10 endpoints that map to real customer actions.

A good rule: if you can’t explain a resource in one sentence (what it is, who owns it, how it’s used), keep it private until you learn more from usage.

Pick a small set of stable nouns (resources) customers already use in conversation, and keep those names stable even if your database changes.

Common starters for SaaS are users, organizations, projects, and events—then add more only when there’s clear demand.

Use the standard meanings and be consistent:

GET = read (no side effects)POST = create or start an actionPATCH = partial updateDELETE = remove or disableThe main win is predictability: clients shouldn’t guess what a method does.

Default to URL versioning like /v1/....

It’s easier to see in logs and screenshots, easier to debug with customers, and simpler to run v1 and v2 side by side when you need a breaking change.

A change is breaking if a correct client can fail without changing their code. Common examples:

Adding a new optional field is usually safe.

Keep it simple:

A practical default is a 90-day window for a first API, so customers have time to migrate without panic.

Pick one pattern and stick to it across all list endpoints.

Always define a default sort and a tie-breaker (like created_at + ) so results don’t jump around.

Start with a clear per-key limit (for example 60 requests/minute plus a small burst), then adjust based on real traffic.

When limiting, return 429 and include:

X-RateLimit-LimitX-RateLimit-RemainingUse one error format everywhere (including 500s). A practical shape is:

code (stable identifier)message (human-readable)details (field-level issues)request_id (for support)Also keep status codes consistent (400/401/403/404/409/429/500) so clients can handle errors cleanly.

If you generate lots of endpoints quickly (for example with Koder.ai), keep the public surface small and treat it as a long-term contract.

Do this before launch:

POST actionsThen publish a tiny SDK that helps with auth, timeouts, retries for safe requests, and pagination—without hiding how the HTTP API works.

idX-RateLimit-ResetRetry-AfterThis makes retries predictable and reduces support tickets.