Oct 05, 2025·8 min

RabbitMQ for Your Applications: Patterns, Setup, and Ops

Learn how to use RabbitMQ in your applications: core concepts, common patterns, reliability tips, scaling, security, and monitoring for production.

Learn how to use RabbitMQ in your applications: core concepts, common patterns, reliability tips, scaling, security, and monitoring for production.

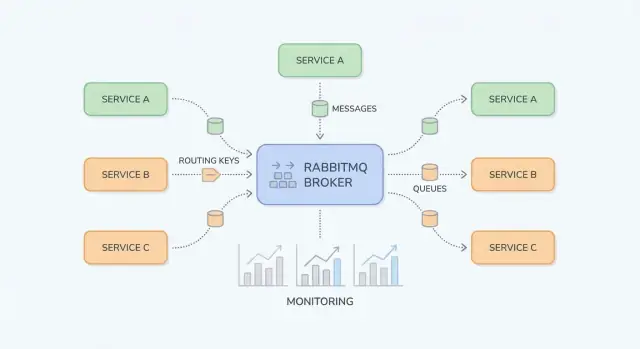

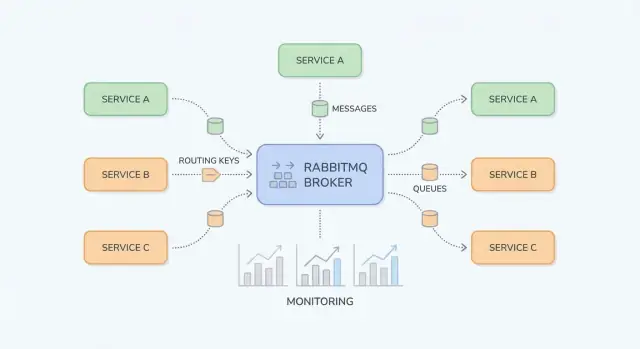

RabbitMQ is a message broker: it sits between parts of your system and reliably moves “work” (messages) from producers to consumers. Application teams usually reach for it when direct, synchronous calls (service-to-service HTTP, shared databases, cron jobs) start creating fragile dependencies, uneven load, and hard-to-debug failure chains.

Traffic spikes and uneven workloads. If your app gets 10× more signups or orders in a short window, processing everything immediately can overwhelm downstream services. With RabbitMQ, producers enqueue tasks quickly and consumers work through them at a controlled pace.

Tight coupling between services. When Service A must call Service B and wait, failures and latency propagate. Messaging decouples them: A publishes a message and continues; B processes it when available.

Safer failure handling. Not every failure should become an error shown to the user. RabbitMQ helps you retry processing in the background, isolate “poison” messages, and avoid losing work during temporary outages.

Teams usually get smoother workloads (buffering peaks), decoupled services (fewer runtime dependencies), and controlled retries (less manual reprocessing). Just as important, it becomes easier to reason about where work is stuck—at the producer, in a queue, or in a consumer.

This guide focuses on practical RabbitMQ for application teams: core concepts, common patterns (pub/sub, work queues, retries and dead-letter queues), and operational concerns (security, scaling, observability, troubleshooting).

It does not aim to be a complete AMQP specification walkthrough or a deep dive into every RabbitMQ plugin. The goal is to help you design message flows that stay maintainable in real systems.

RabbitMQ is a message broker that routes messages between parts of your system, so producers can hand off work and consumers can process it when they’re ready.

With a direct HTTP call, Service A sends a request to Service B and typically waits for a response. If Service B is slow or down, Service A either fails or stalls, and you have to handle timeouts, retries, and backpressure in every caller.

With RabbitMQ (commonly via AMQP), Service A publishes a message to the broker. RabbitMQ stores and routes it to the right queue(s), and Service B consumes it asynchronously. The key shift is that you’re communicating through a durable middle layer that buffers spikes and smooths out uneven workloads.

Messaging is a good fit when you:

Messaging is a poor fit when you:

Synchronous (HTTP):

A checkout service calls an invoicing service over HTTP: “Create invoice.” The user waits while invoicing runs. If invoicing is slow, checkout latency increases; if it’s down, checkout fails.

Asynchronous (RabbitMQ):

Checkout publishes invoice.requested with the order id. The user gets an immediate confirmation that the order was received. Invoicing consumes the message, generates the invoice, then publishes invoice.created for email/notifications to pick up. Each step can retry independently, and temporary outages don’t automatically break the entire flow.

RabbitMQ is easiest to understand if you separate “where messages are published” from “where messages are stored.” Producers publish to exchanges; exchanges route to queues; consumers read from queues.

An exchange doesn’t store messages. It evaluates rules and forwards messages to one or more queues.

billing or email).region=eu AND tier=premium), but keep it for special cases because it’s harder to reason about.A queue is where messages sit until a consumer processes them. A queue can have one consumer or many (competing consumers), and messages are typically delivered to one consumer at a time.

A binding connects an exchange to a queue and defines the routing rule. Think of it as: “When a message hits exchange X with routing key Y, deliver it to queue Q.” You can bind multiple queues to the same exchange (pub/sub) or bind a single queue multiple times for different routing keys.

For direct exchanges, routing is exact. For topic exchanges, routing keys look like dot-separated words, such as:

orders.createdorders.eu.refundedBindings can include wildcards:

* matches exactly one word (e.g., orders.* matches orders.created)# matches zero or more words (e.g., orders.# matches orders.created and orders.eu.refunded)This gives you a clean way to add new consumers without changing producers—create a new queue and bind it with the pattern you need.

After RabbitMQ delivers a message, the consumer reports what happened:

Be careful with requeue: a message that always fails can loop forever and block the queue. Many teams pair nacks with a retry strategy and a dead-letter queue (covered later) so failures are handled predictably.

RabbitMQ shines when you need to move work or notifications between parts of your system without making everything wait on a single slow step. Below are practical patterns that show up in everyday products.

When multiple consumers should react to the same event—without the publisher knowing who they are—publish/subscribe is a clean fit.

Example: when a user updates their profile, you might notify search indexing, analytics, and a CRM sync in parallel. With a fanout exchange you broadcast to all bound queues; with a topic exchange you route selectively (e.g., user.updated, user.deleted). This avoids tightly coupling services and lets teams add new subscribers later without changing the producer.

If a task takes time, push it to a queue and let workers process it asynchronously:

This keeps web requests fast while allowing you to scale workers independently. It’s also a natural way to control concurrency: the queue becomes your “to-do list,” and worker count becomes your “throughput knob.”

Many workflows cross service boundaries: order → billing → shipping is the classic example. Instead of one service calling the next and blocking, each service can publish an event when it finishes its step. Downstream services consume events and continue the workflow.

This improves resilience (a temporary outage in shipping doesn’t break checkout) and makes ownership clearer: each service reacts to events it cares about.

RabbitMQ is also a buffer between your app and dependencies that can be slow or flaky (third-party APIs, legacy systems, batch databases). You enqueue requests quickly, then process them with controlled retries. If the dependency is down, work accumulates safely and drains later—rather than causing timeouts across your whole application.

If you’re planning to introduce queues gradually, a small “async outbox” or single background-job queue is often a good first step (see /blog/next-steps-rollout-plan).

A RabbitMQ setup stays pleasant to work with when routes are easy to predict, names are consistent, and payloads evolve without breaking older consumers. Before adding another queue, make sure the “story” of a message is obvious: where it originates, how it’s routed, and how a teammate can debug it end-to-end.

Picking the right exchange upfront reduces one-off bindings and surprise fan-outs:

billing.invoice.created).billing.*.created, *.invoice.*). This is the most common choice for maintainable event-style routing.A good rule: if you’re “inventing” complex routing logic in code, it may belong in a topic exchange pattern instead.

Treat message bodies like public APIs. Use explicit versioning (for example, a top-level field like schema_version: 2) and aim for backward compatibility:

This keeps older consumers working while new ones adopt the new schema on their own schedule.

Make troubleshooting cheap by standardizing metadata:

correlation_id: ties together commands/events that belong to the same business action.trace_id (or W3C traceparent): links messages to distributed tracing across HTTP and async flows.When every publisher sets these consistently, you can follow a single transaction across multiple services without guesswork.

Use predictable, searchable names. One common pattern:

<domain>.<type> (e.g., billing.events)<domain>.<entity>.<verb> (e.g., billing.invoice.created)<service>.<purpose> (e.g., reporting.invoice_created.worker)Consistency beats cleverness: future you (and your on-call rotation) will thank you.

Reliable messaging is mostly about planning for failure: consumers crash, downstream APIs time out, and some events are simply malformed. RabbitMQ gives you the tools, but your application code has to cooperate.

A common setup is at-least-once delivery: a message may be delivered more than once, but it shouldn’t be silently lost. This typically happens when a consumer receives a message, starts work, and then fails before acknowledging it—RabbitMQ will requeue and redeliver.

The practical takeaway: duplicates are normal, so your handler must be safe to run multiple times.

Idempotency means “processing the same message twice has the same effect as processing it once.” Useful approaches include:

message_id (or business key like order_id + event_type + version) and store it in a “processed” table/cache with a TTL.PENDING) or database uniqueness constraints to prevent double-creates.Retries are best treated as a separate flow, not a tight loop in your consumer.

A common pattern is:

This creates backoff without keeping messages “stuck” as unacked.

Some messages will never succeed (bad schema, missing referenced data, code bug). Detect them by:

Route these to a DLQ for quarantine. Treat the DLQ as an operational inbox: inspect payloads, fix the underlying issue, then manually replay selected messages (ideally through a controlled tool/script) rather than dumping everything back into the main queue.

RabbitMQ performance is usually limited by a few practical factors: how you manage connections, how fast consumers can safely process work, and whether queues are being used as “storage.” The goal is steady throughput without building a growing backlog.

A common mistake is opening a new TCP connection for every publisher or consumer. Connections are heavier than you think (handshakes, heartbeats, TLS), so keep them long-lived and reuse them.

Use channels to multiplex work over a smaller number of connections. As a rule of thumb: few connections, many channels. Still, don’t create thousands of channels blindly—each channel has overhead, and your client library may have its own limits. Prefer a small channel pool per service and reuse channels for publishing.

If consumers pull too many messages at once, you’ll see memory spikes, long processing times, and uneven latency. Set a prefetch (QoS) so each consumer only holds a controlled number of unacked messages.

Practical guidance:

Large messages reduce throughput and increase memory pressure (on publishers, brokers, and consumers). If your payload is big (e.g., documents, images, large JSON), consider storing it elsewhere (object storage or a database) and sending only an ID + metadata through RabbitMQ.

A good heuristic: keep messages in the KB range, not MB.

Queue growth is a symptom, not a strategy. Add backpressure so producers slow down when consumers can’t keep up:

When in doubt, change one knob at a time and measure: publish rate, ack rate, queue length, and end-to-end latency.

Security for RabbitMQ is mostly about tightening the “edges”: how clients connect, who can do what, and how you keep credentials out of the wrong places. Use this checklist as a baseline, then adapt it to your compliance needs.

RabbitMQ permissions are powerful when you use them consistently.

For operational hardening (ports, firewalls, and auditing), keep a short internal runbook and link it from /docs/security so teams follow one standard.

When RabbitMQ misbehaves, symptoms show up in your application first: slow endpoints, timeouts, missing updates, or jobs that “never finish.” Good observability lets you confirm whether the broker is the cause, spot the bottleneck (publisher, broker, or consumer), and act before users notice.

Start with a small set of signals that tell you whether messages are flowing.

Alert on trends, not just absolute thresholds.

Broker logs help you separate “RabbitMQ is down” from “clients are misusing it.” Look for authentication failures, blocked connections (resource alarms), and frequent channel errors. On the application side, make sure each processing attempt logs a correlation ID, queue name, and outcome (acked, rejected, retried).

If you use distributed tracing, propagate trace headers through message properties so you can connect “API request → published message → consumer work.”

Build one dashboard per critical flow: publish rate, ack rate, depth, unacked, requeues, and consumer count. Add links directly in the dashboard to your internal runbook, e.g. /docs/monitoring, and a “what to check first” checklist for on-call responders.

When something “just stops moving” in RabbitMQ, resist the urge to restart first. Most issues become obvious once you look at (1) bindings and routing, (2) consumer health, and (3) resource alarms.

If publishers report “sent successfully” but queues stay empty (or the wrong queue fills), check routing before code.

Start in the Management UI:

topic exchanges).If the queue has messages but nothing is consuming, confirm:

Duplicates typically come from retries (consumer crash after processing but before ack), network interruptions, or manual requeueing. Mitigate by making handlers idempotent (e.g., de-dupe by message ID in a database).

Out-of-order delivery is expected when you have multiple consumers or requeues. If order matters, use a single consumer for that queue, or partition by key into multiple queues.

Alarms mean RabbitMQ is protecting itself.

Before replaying, fix the root cause and prevent “poison message” loops. Requeue in small batches, add a retry cap, and stamp failures with metadata (attempt count, last error). Consider sending replayed messages to a separate queue first, so you can stop quickly if the same error repeats.

Picking a messaging tool is less about “best” and more about matching your traffic pattern, failure tolerance, and operational comfort.

RabbitMQ shines when you need reliable message delivery and flexible routing between application components. It’s a strong choice for classic async workflows—commands, background jobs, fan-out notifications, and request/response patterns—especially when you want:

If your applications are event-driven but the primary goal is moving work rather than retaining a long event history, RabbitMQ is often a comfortable default.

Kafka and similar platforms are built for high-throughput streaming and long-lived event logs. Choose a Kafka-like system when you need:

Trade-off: Kafka-style systems can have higher operational overhead and may push you toward throughput-oriented design (batching, partition strategy). RabbitMQ tends to be easier for low-to-moderate throughput with lower end-to-end latency and complex routing.

If you have one app producing jobs and one worker pool consuming them—and you’re fine with simpler semantics—a Redis-based queue (or managed task service) can be sufficient. Teams typically outgrow it when they need stronger delivery guarantees, dead-lettering, multiple routing patterns, or clearer separation between producers and consumers.

Design your message contracts as if you might move later:

If you later need replayable streams, you can often bridge RabbitMQ events into a log-based system while keeping RabbitMQ for operational workflows. For a practical rollout plan, see /blog/rabbitmq-rollout-plan-and-checklist.

Rolling out RabbitMQ works best when you treat it as a product: start small, define ownership, and prove reliability before expanding to more services.

Pick a single workflow that benefits from async processing (e.g., sending emails, generating reports, syncing to a third-party API).

If you need a reference template for naming, retry tiers, and basic policies, keep it centralized in /docs.

As you implement these patterns, consider standardizing the scaffolding across teams. For example, teams using Koder.ai often generate a small producer/consumer service skeleton from a chat prompt (including naming conventions, retry/DLQ wiring, and trace/correlation headers), then export the source code for review and iterate in “planning mode” before rollout.

RabbitMQ succeeds when “someone owns the queue.” Decide this before production:

If you’re formalizing support or managed hosting, align expectations early (see /pricing) and set a contact route for incidents or onboarding help at /contact.

Run small, time-boxed exercises to build confidence:

Once one service is stable for a few weeks, replicate the same patterns—don’t reinvent them per team.

Use RabbitMQ when you want to decouple services, absorb traffic spikes, or move slow work off the request path.

Good fits include background jobs (emails, PDFs), event notifications to multiple consumers, and workflows that should keep running during temporary downstream outages.

Avoid it when you truly need an immediate response (simple reads/validation) or when you can’t commit to versioning, retries, and monitoring—those aren’t optional in production.

Publish to an exchange and route into queues:

orders.* or orders.#.Most teams default to topic exchanges for maintainable event-style routing.

A queue stores messages until a consumer processes them; a binding is the rule that connects an exchange to a queue.

To debug routing issues:

These three checks explain most “published but not consumed” incidents.

Use a work queue when you want one of many workers to process each task.

Practical setup tips:

At-least-once delivery means a message can be delivered more than once (for example, if a consumer crashes after doing work but before ack).

Make consumers safe by:

message_id (or business key) and recording processed IDs with a TTL.Assume duplicates are normal, and design for them.

Avoid tight requeue loops. A common approach is “retry queues” plus DLQ:

Replay from DLQ only after fixing the root cause, and do it in small batches.

Start with predictable names and treat messages like public APIs:

schema_version to payloads.Also standardize metadata:

Focus on a few signals that show whether work is flowing:

Alert on trends (e.g., “backlog growing for 10 minutes”), then use logs that include queue name, correlation_id, and the processing outcome (acked/retried/rejected).

Do the basics consistently:

Keep a short internal runbook so teams follow one standard (for example, link from /docs/security).

Start by locating where the flow stops:

Restarting is rarely the first or best move.

correlation_id to tie events/commands to one business action.trace_id (or W3C trace headers) to connect async work to distributed traces.This makes onboarding and incident response much easier.