Oct 11, 2025·8 min

Rasmus Lerdorf and PHP: From Personal Tool to Web Staple

The story of Rasmus Lerdorf and PHP—how a small set of web scripts became a widely used platform, and why PHP still powers many sites today.

The story of Rasmus Lerdorf and PHP—how a small set of web scripts became a widely used platform, and why PHP still powers many sites today.

PHP didn’t start as a grand platform or a carefully designed language. It began because Rasmus Lerdorf wanted to solve a concrete problem: maintain a personal website without doing repetitive manual work.

That detail matters because it explains a lot about why PHP feels the way it does—even today.

Lerdorf was a developer building for the early web, when pages were mostly static and updating anything beyond plain HTML quickly became tedious. He wanted simple scripts that could track visitors, reuse common page parts, and generate content dynamically.

In other words: he wanted tools that helped him ship changes faster.

“Personal tools” wasn’t a brand name—it was a mindset. Early web builders often wrote small utilities to automate the boring parts:

PHP’s earliest versions were shaped by that practical, get-it-done approach.

Once you know PHP’s roots, many of its traits make more sense: the focus on embedding code directly into HTML, the large standard library aimed at common web tasks, and the preference for convenience over academic purity.

These choices helped PHP spread quickly, but they also created trade-offs we’ll cover later.

This article walks through how PHP grew from Lerdorf’s scripts into a community-driven language, why it fit hosting and the LAMP stack so well, how ecosystems like WordPress amplified it, and what modern PHP (7 and 8+) changed—so you can judge PHP today based on reality, not nostalgia or hype.

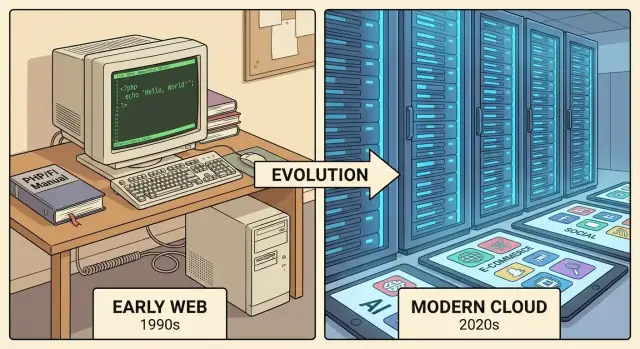

The mid-1990s web was mostly static HTML. If you wanted anything dynamic—processing a form, showing a hit counter, customizing a page per visitor—you typically reached for CGI scripts, often written in Perl.

That worked, but it wasn’t smooth.

CGI programs ran as separate processes for each request. For simple tasks, that meant a lot of moving parts: a script file with careful permissions, server configuration, and a mental model that didn’t feel like “writing a web page.” You weren’t just mixing a little logic into HTML; you were building a tiny program that output HTML as text.

For hobby sites and small businesses, the common needs were repetitive and practical:

Most people were on shared hosting with limited CPU, memory, and little control over server settings. Installing custom modules or long‑running services wasn’t realistic. What you could do was upload files and run simple scripts.

These constraints pushed toward a tool that:

That gap—between static pages and heavyweight scripting—was the everyday web problem PHP set out to solve.

Rasmus Lerdorf didn’t set out to invent a programming language. He wanted something much more ordinary: a better way to run his own website.

The earliest “PHP” work began as a collection of small C programs he used to track visits to his online resume, plus a few utilities to handle basic site tasks without constantly hand‑editing pages.

At the time, knowing who was visiting your site (and how often) wasn’t as simple as dropping in an analytics snippet. Lerdorf’s scripts helped log and summarize requests, making it easier to understand traffic patterns.

Alongside that, he built helpers for common website chores—simple templating, small bits of dynamic output, and form handling—so the site could feel “alive” without becoming a full custom application.

Once you have tools for request tracking, form processing, and reusing page components, you’ve accidentally built something other people can use too.

That’s the key moment: the functionality wasn’t tied to one layout or one page. It was general enough that other site owners could imagine copying the approach for their own projects.

Because it started as a toolbox, the ergonomics were practical: do the common thing quickly, don’t over‑design, and keep the barrier to entry low.

That attitude—usefulness first, polish later—helped PHP feel approachable from the beginning.

The takeaway is simple: PHP’s roots weren’t academic or theoretical. They were problem‑driven, aimed at getting a real website working with less friction.

PHP didn’t start as a “language” in the way people think of it today. The first public milestone was PHP/FI, which stood for “Personal Home Page / Forms Interpreter.”

That name is revealing: it wasn’t trying to be everything. It was meant to help people build dynamic pages and process web forms without writing a full custom program for every task.

PHP/FI bundled a few practical ideas that, together, made early web development much less painful:

It wasn’t polished, but it reduced the amount of glue code people had to write just to get a page working.

Early websites quickly hit a wall: as soon as you wanted feedback forms, guestbooks, sign-ups, or basic search, you needed to accept user input and do something with it.

PHP/FI made form handling a core use case. Instead of treating forms as an advanced feature, it leaned into them—making it easier to read submitted values and generate a response page.

That focus matched what everyday site owners were trying to build.

One of PHP/FI’s most influential ideas was its templating style: keep HTML as the main document, and weave in small pieces of server logic.

<!-- HTML-first, with small dynamic pieces -->

<p>Hello, <?php echo $name; ?>!</p>

To designers and tinkerers, this felt natural: you could edit a page and add “just enough” dynamic behavior without adopting a totally separate system.

PHP/FI wasn’t elegant, and it didn’t aim to be. People adopted it because it was:

Those “killer features” weren’t flashy—they were exactly what the early web needed.

Rasmus Lerdorf’s early PHP scripts were built to solve his own problems: track visitors, reuse common page elements, and avoid repeating work.

What turned that small set of utilities into “PHP” as most people recognize it wasn’t a single big rewrite—it was a steady pull from other developers who wanted the same convenience for their own sites.

As soon as PHP was shared publicly, users began sending fixes, small features, and ideas. That feedback loop mattered: the project started to reflect the needs of many webmasters instead of one personal site.

Documentation improved, edge cases got patched, and the language began to develop conventions that made it easier to pick up and use.

A major turning point was PHP 3, which rewrote the core engine and introduced the name “PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor.” This wasn’t just branding.

The rewrite made the language more consistent and easier to extend, which meant PHP could grow without becoming an unmaintainable pile of one‑off scripts.

A broader user community also pushed for integrations with the tools they relied on. Extensions started to appear that connected PHP to different databases and services, so you weren’t locked into a single setup.

Instead of “a scripting tool that outputs HTML,” PHP became a practical way to build data‑driven websites—guestbooks, forums, catalogs, and early e‑commerce.

That’s the key shift: community contributions didn’t merely add features. They changed PHP’s role from a helpful toolkit into a shared, extensible platform people could bet real projects on.

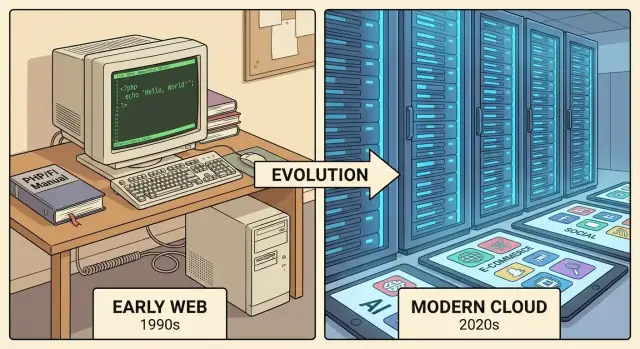

PHP didn’t become a default choice for so many websites just because it was easy to pick up. A big part of the story is that the “engine” under the hood got a serious upgrade—one that made PHP faster, more consistent, and easier to extend.

Zend (founded by Andi Gutmans and Zeev Suraski) introduced the Zend Engine as a new core for PHP. Think of it as replacing the motor while keeping the same car model.

Developers could still write familiar PHP code, but the runtime became better structured internally.

That structure mattered because it enabled:

PHP 4 (powered by Zend Engine 1) arrived at the perfect time for the web’s “rent a slice of a server” model.

Shared hosting providers could offer PHP broadly and cheaply, and many did. This availability became a growth loop: more hosts supported PHP, so more people used it; more usage pushed hosts to keep supporting it.

In practical terms, PHP 4 was “good enough, everywhere.” That ubiquity mattered as much as any language feature.

PHP 5 (Zend Engine 2) pushed PHP forward for teams building larger codebases. The headline change was stronger object‑oriented programming: better class handling, improved visibility rules, and a foundation for more modern patterns.

It wasn’t about making PHP academic—it was about making it easier to organize real projects, reuse code, and maintain applications over time.

As PHP spread, a new pressure emerged: people began to expect old code to keep running. Hosting companies, CMS platforms, and agencies depended on stability.

From this point on, PHP’s evolution wasn’t just “add features”—it was also “don’t break the internet.”

PHP didn’t win because it was the most elegant language on paper. It won because it made building useful web pages feel immediate.

For early web developers—often designers, hobbyists, or small businesses—PHP lowered the time‑to‑first‑working‑thing more than almost any alternative.

With PHP, the feedback loop was almost frictionless: upload a file, refresh the page, see results. That sounds trivial, but it shaped a generation of web building.

People could start with a single dynamic page (a contact form, a guestbook, a counter) and grow from there.

Early web projects rarely had big engineering departments. They had one developer, maybe two, and a pile of urgent requests.

PHP fit that reality: it reduced the ceremony around deployment and made incremental changes easy to ship.

PHP rode a wave of cheap shared hosting. Many providers preinstalled it, so you didn’t need special infrastructure or expensive servers.

Deployment often meant “copy the files over,” which matched how people already published HTML.

As PHP adoption grew, it became self‑reinforcing. Tutorials, snippets, forums, and copy‑paste examples were everywhere.

That community memory made PHP feel approachable—even when the underlying web problems were anything but.

PHP didn’t just succeed because the language was easy to pick up—it succeeded because it had a “default home” on the early web.

That home was the LAMP stack: Linux + Apache + MySQL + PHP. For years, this combo was the standard recipe for running dynamic websites, especially for small businesses and personal projects.

Linux and Apache were widely available and inexpensive to run. PHP fit neatly into Apache’s request/response model: a visitor hit a URL, Apache handed the request to PHP, and PHP generated HTML on the fly.

There was no separate application server to manage, which kept deployments simple and cheap.

MySQL completed the picture. PHP’s built‑in database extensions made it straightforward to connect to MySQL, run queries, and render results in a webpage.

That tight integration meant a huge percentage of “database-backed sites” could be built with the same familiar tools.

A major accelerant was shared hosting. Many hosts offered accounts where PHP and MySQL were already configured—no system administration required.

With control panels like cPanel, users could create a MySQL database, manage tables in phpMyAdmin, upload PHP files over FTP, and go live quickly.

Then came one‑click installers (often for WordPress, forums, and shopping carts). These installers normalized the idea that “a website is a PHP app + a MySQL database,” making PHP the path of least resistance for millions of site owners.

The stack encouraged a practical workflow: edit a .php file, refresh the browser, tweak SQL, repeat.

It also shaped familiar patterns—templates and includes, form handling, sessions, and CRUD pages—creating a shared mental model for web building that lasted well beyond LAMP’s peak.

PHP didn’t become “everywhere” purely because of its syntax. It became a default choice because complete, installable products formed around it—tools that solved real business problems with minimal setup.

Content management systems turned PHP into a one‑click decision. Platforms like WordPress, Drupal, and Joomla bundled the hard parts—admin panels, logins, permissions, themes, plugins—so a site owner could publish pages without writing code.

That matters because each CMS created its own gravity: designers learned theme building, agencies built repeatable offerings, and plugin marketplaces grew.

Once a client’s site depended on that ecosystem, PHP was “chosen” again and again—sometimes without the client even knowing.

Online stores and community sites were early web essentials, and PHP fit the shared-hosting reality of the time.

Software like Magento (and later WooCommerce on WordPress), plus forum apps such as phpBB, gave people ready-made solutions for catalogs, carts, accounts, and moderation.

These projects also normalized a workflow where you install an app, configure it in a browser, and extend it with modules—exactly the kind of development that helped PHP thrive.

Not all PHP is public‑facing. Many teams use it for internal dashboards, admin tools, and straightforward APIs that connect payments, inventory, CRM systems, or analytics.

These systems don’t show up in “what CMS is this?” scans, but they keep PHP in day‑to‑day use.

When a large share of the web runs on a few massive products (especially WordPress), the language underneath inherits that footprint.

PHP’s reach is, in large part, the reach of the ecosystems built on top of it—not just a reflection of the language itself.

PHP’s success has always been tied to pragmatism—and pragmatism often leaves rough edges.

Many critiques are rooted in real history, but not all of them reflect how PHP is used (or written) today.

A frequent complaint is inconsistency: function names that follow different patterns, parameters ordered differently, and older APIs living alongside newer ones.

That’s not imagined—it’s the result of PHP growing quickly, adding features as the web changed, and keeping older interfaces working for millions of existing sites.

PHP also supports multiple programming styles. You can write simple “just get it done” scripts, or more structured, object‑oriented code.

Critics call this “mixed paradigms”; supporters call it flexibility. The downside is that teams can end up with uneven code quality if they don’t set standards.

“PHP is insecure” is an oversimplification. Most PHP security incidents come from application mistakes: trusting user input, building SQL queries by string concatenation, misconfiguring file uploads, or forgetting access checks.

PHP’s historical defaults didn’t always steer beginners toward safe patterns, and its ease of use meant many beginners deployed public‑facing code.

The more accurate take: PHP makes it easy to build web apps, and web apps are easy to get wrong without basic security hygiene.

PHP has carried a heavy responsibility: don’t break the web.

This backward compatibility keeps long‑lived apps running for years, but it also means legacy code sticks around—sometimes far past its “best by” date. Companies may spend more effort maintaining old patterns than adopting better ones.

Fair critique: inconsistency, legacy APIs, and uneven codebases are real.

Outdated critique: assuming modern PHP projects must look like early‑2000s PHP, or that the language itself is the primary security weakness.

In practice, the difference is usually the team’s practices, not the tool.

PHP’s reputation is often tied to code written years ago: mixed HTML and logic in one file, inconsistent styles, and “it works on my server” deployment habits.

PHP 7 and 8+ didn’t just add features—they nudged the ecosystem toward cleaner, faster, more maintainable work.

PHP 7 delivered major performance improvements by redesigning key internals (the Zend Engine update).

In plain terms: the same app could handle more requests on the same hardware, or cost less to run at the same traffic.

That mattered for shared hosting, busy WordPress sites, and any business that measured “page load time” in lost sales. It also made PHP feel competitive again against newer server-side options.

PHP 8 introduced features that make large codebases easier to reason about:

int|string). This reduces guesswork and improves tooling support.Modern PHP projects usually rely on Composer, the standard dependency manager.

Instead of copying libraries by hand, teams declare dependencies in a file, install predictable versions, and use autoloading. This is one reason contemporary PHP feels far more “professional” than the old copy‑paste era.

Old PHP often meant ad‑hoc scripts; modern PHP tends to mean versioned dependencies, frameworks, typed code, automated testing, and performance that holds up under real traffic.

PHP isn’t a nostalgia pick—it’s a practical tool that still fits many web jobs extremely well.

The key is matching it to your constraints, not your ideology.

PHP shines when you’re building or running:

If your project benefits from “many developers already know this, and hosting is everywhere,” PHP can reduce friction.

Consider alternatives if you need:

It can also be worth choosing a different stack when you’re building a brand-new product and want strong defaults for modern architecture (typed APIs, structured services, and a clearer separation of concerns).

Ask these before choosing:

One lesson from PHP’s origin story is timeless: the winning tools shrink the gap between idea and working software.

If you’re evaluating whether to keep investing in PHP or to build a new service alongside it (for example, a React frontend with a Go API), a fast prototype can remove a lot of guesswork. Platforms like Koder.ai are built for that “ship-first” workflow: you can describe an app in chat, generate a working web or backend project (React + Go with PostgreSQL), and iterate rapidly with features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback—then export the source code when you’re ready.

For more practical guides, browse /blog. If you’re comparing deployment or service options, /pricing can help frame costs.

Rasmus Lerdorf built a set of small C-based utilities to maintain his personal site—tracking visitors, reusing page parts, and handling simple dynamic output.

Because the goal was to remove repetitive web chores (not to design a “perfect” language), PHP kept a practicality-first feel: quick to deploy, easy to embed in HTML, and packed with web-focused helpers.

In the mid-1990s, most pages were static HTML. Anything dynamic (forms, counters, per-user content) often meant CGI scripts—commonly in Perl.

That worked, but it was awkward for everyday site updates because you typically wrote a separate program that printed HTML, rather than editing an HTML page with small bits of server logic.

CGI programs usually ran as separate processes per request, and required more setup (permissions, server config, and a different mental model).

PHP made dynamic output feel closer to “editing a web page”: write HTML, add small server-side snippets, upload, refresh.

PHP/FI stood for “Personal Home Page / Forms Interpreter.” It was an early public version focused on building dynamic pages and processing forms.

Its “killer” idea was being able to embed server-side code directly in pages while also providing built-in conveniences for common web tasks (especially forms and basic database access).

It lowered the barrier for non-specialists: you could keep HTML as the main document and insert small dynamic pieces (like outputting a name or looping through results).

This approach matched how people built sites on shared hosting—incrementally—without adopting a completely separate templating system upfront.

As soon as PHP was shared publicly, other developers began contributing fixes, features, and integrations.

That shifted PHP from “one person’s toolbox” into an ecosystem-driven project, where real-world webmaster needs (databases, extensions, portability) shaped the language’s direction.

PHP 3 was a major rewrite that made PHP more consistent and easier to extend, and it introduced the name “PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor.”

Practically, it marked the point where PHP became a more stable, extensible platform instead of a growing pile of one-off scripts.

The Zend Engine (used prominently in PHP 4 and PHP 5) improved PHP’s runtime internals—better structure, better performance, and a clearer path for extensions.

That mattered because hosting providers could offer PHP broadly and cheaply, and teams could build larger codebases with more predictable behavior.

LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP) became a default recipe for dynamic sites, especially on shared hosting.

PHP fit Apache’s request/response model well, and its database connectivity made MySQL-backed pages straightforward—so millions of sites standardized on the same stack and workflow.

Modern PHP (7 and 8+) brought big performance gains and more maintainable language features, while Composer standardized dependency management.

To evaluate PHP today, focus on your constraints:

If you’re extending an existing PHP system, incremental modernization is often cheaper than a rewrite.