Nov 05, 2025·8 min

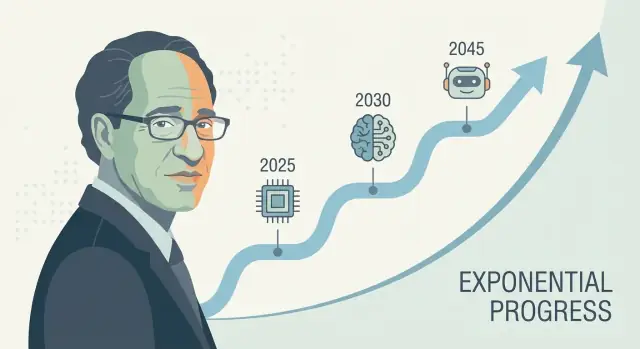

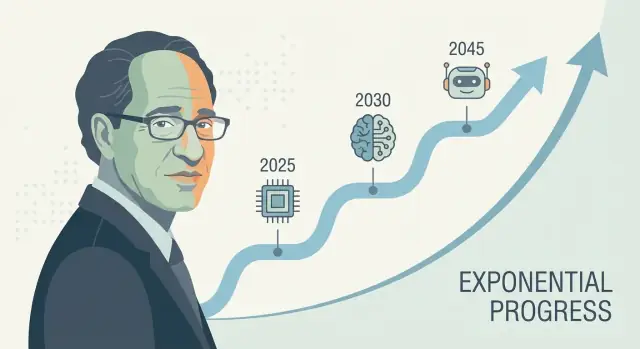

Ray Kurzweil’s AGI Timeline: How He Forecasts Decades Ahead

Explore Ray Kurzweil’s long-range AGI predictions: his timelines, forecasting approach, hits and misses, critiques, and what signals to track next.

Explore Ray Kurzweil’s long-range AGI predictions: his timelines, forecasting approach, hits and misses, critiques, and what signals to track next.

Ray Kurzweil is one of the most recognized voices in long-range technology forecasting—especially around artificial intelligence and the technological singularity. When he makes a concrete AGI prediction (often framed as a date, not a vague “someday”), it tends to ripple outward: investors cite it, journalists debate it, and researchers get asked to respond.

Kurzweil’s influence isn’t just about optimism. It’s about offering a repeatable narrative for why progress should accelerate—often tied to exponential growth in computing and the idea that each generation of tools helps build the next. Whether you agree or not, he provides a structured way to discuss an artificial general intelligence timeline rather than treating it as pure science fiction.

A decades-ahead forecast is less about guessing a calendar date and more about projecting a bundle of trends forward: compute, cost, data, algorithms, and the practical ability to build systems that generalize. The bet is that these curves keep moving—and that today’s “missing pieces” are solvable engineering problems that shrink as inputs improve.

This piece breaks down:

Even among serious experts, AGI prediction timelines vary widely because they depend on assumptions: what “AGI” means, which bottlenecks matter most, and how quickly breakthroughs translate into reliable products. Kurzweil’s timelines are influential not because they’re guaranteed, but because they’re specific enough to test—and hard enough to ignore.

Ray Kurzweil is an American inventor, author, and futurist known for making long-range technology forecasts—and for backing them with charts, historical data, and bold deadlines.

Kurzweil first became widely known through practical inventions, especially in speech and text technologies. He built companies focused on optical character recognition (OCR), text-to-speech, and music tools, and he’s spent decades close to real product constraints: data quality, hardware costs, and what users will actually adopt. That builder’s mindset shapes his forecasts—he tends to treat progress as something that can be engineered and scaled.

He also worked inside major tech organizations (including Google), reinforcing his view that big leaps often come from sustained investment, better tooling, and compounding improvements—not just isolated breakthroughs.

Kurzweil’s AGI timeline is usually discussed through his popular books, especially The Age of Spiritual Machines (1999) and The Singularity Is Near (2005). These works argue that information technologies improve in accelerating, compounding ways—and that this acceleration will eventually produce machines with human-level (and then beyond-human-level) capabilities.

Whether you agree or not, his writing helped set the terms of the public conversation: AI progress as measurable, trend-driven, and (at least in principle) forecastable.

AGI (Artificial General Intelligence): an AI system that can learn and perform a wide range of tasks at roughly human level, adapting to new problems without being narrowly specialized.

Singularity: Kurzweil’s term for a period when technological progress becomes so rapid (and AI so capable) that it changes society in unpredictable, hard-to-model ways.

Timeline: a forecast with dates and milestones (for example, “human-level AI by year X”), not just a general claim that progress will continue.

Kurzweil has repeatedly argued that human-level artificial general intelligence (AGI) is likely within the first half of the 21st century—most famously clustering around the late 2020s to 2030s in public talks and books. He isn’t always rigid about a single year, but the central claim is consistent: once computing power, data, and algorithms cross certain thresholds, systems will match the breadth and adaptability of human cognition.

In Kurzweil’s framing, AGI isn’t the finish line—it’s a trigger. After machines reach (and then exceed) human-level general intelligence, progress compounds: smarter systems help design even smarter systems, accelerating scientific discovery, automation, and human–machine integration. That compounding dynamic is what he ties to the broader “technological singularity” idea: a period where change becomes so rapid that everyday intuition stops being a reliable guide.

A key nuance in his timeline claims is the definition of AGI. Today’s leading models can be impressive across many tasks, but they still tend to be:

Kurzweil’s “AGI” implies a system that can transfer learning across domains, form and pursue goals in novel situations, and reliably handle the open-ended variety of the real world—not just excel in benchmarks.

A calendar prediction is easy to debate and hard to use. Milestones are more practical: sustained autonomous learning, reliable tool use and planning, strong performance in messy real-world environments, and clear economic substitution across many job types. Even if you disagree with his exact timing, these checkpoints make the forecast testable—and more useful than betting on one headline year.

Kurzweil is often described as a “serial predictor,” and that reputation is part of why his AGI timeline gets attention. But his track record is mixed in a way that’s useful for understanding forecasting: some calls were specific and measurable, others were directionally right but fuzzy, and a few missed important constraints.

Across books and talks, he’s associated with forecasts such as:

Clear, checkable predictions are tied to a date and a measurable outcome: “by year X, Y technology will reach Z performance,” or “a majority of devices will have feature F.” These can be tested against public benchmarks (accuracy rates, sales/adoption data, compute costs).

Vague predictions sound plausible but are hard to falsify, such as “computers will be everywhere,” “AI will transform society,” or “humans will merge with technology.” These may feel true even if the details, timing, or mechanism differ.

A practical way to evaluate any forecaster is to separate direction, timing, and specificity.

The point isn’t to label forecasts as “good” or “bad.” It’s to notice how confident, data-driven predictions can still hinge on hidden assumptions—especially when they involve messy social adoption, not just improving hardware or algorithms.

Kurzweil’s “Law of Accelerating Returns” is the idea that when a technology improves, those improvements often make it easier to improve it again. That creates a feedback loop where progress speeds up over time.

A straight-line (linear) trend is like adding the same amount every year: 1, 2, 3, 4.

An exponential trend is like multiplying: 1, 2, 4, 8. Early on it looks slow—then it suddenly feels like everything is happening at once. Kurzweil argues many technologies (especially information technologies) follow this pattern because each generation of tools helps build the next.

Kurzweil doesn’t just ask “Can we do X?” He asks “How cheaply can we do X?” A common pattern in computing is: performance rises while cost falls. When the cost to run a useful model drops, more people can experiment, deploy products, and fund the next wave—speeding up progress.

This is why he pays attention to long-run curves like “computations per dollar,” not just headline demos.

Moore’s law is the classic example: for decades, the number of transistors on chips roughly doubled on a regular schedule, pushing computers to get faster and cheaper.

Kurzweil’s argument isn’t “Moore’s law will continue forever.” It’s broader: even if one hardware approach slows, other methods (better chips, GPUs/TPUs, parallelism, new architectures, software efficiency) can keep the overall cost/performance trend improving.

People often predict the future by extending recent change at the same pace. That misses compounding. It can make early progress look unimpressive—and later progress look “sudden,” when it may have been building predictably on a curve for years.

Forecasts like Kurzweil’s usually start with measurable trends—things you can put on a chart. That’s a strength: you can debate the inputs instead of arguing purely on intuition. It’s also where the biggest limitations show up.

Technology forecasters often track:

These curves can be compelling because they’re long-running and frequently updated. If your view of AGI is “enough hardware plus the right software,” these datasets can feel like solid footing.

The main gap: more hardware doesn’t automatically produce smarter systems. AI capability depends on algorithms, data quality, training recipes, tooling, and human feedback—not just FLOPs.

A useful way to think about it is: hardware is a budget, capability is the result. The relationship between the two is real, but it isn’t fixed. Sometimes a small algorithmic change unlocks big gains; sometimes scaling hits diminishing returns.

To connect “inputs” (compute, money) to “outputs” (what models can actually do), forecasters need:

Benchmarks can be gamed, so the most convincing signals combine test scores with evidence of durable usefulness.

Two frequent mistakes are cherry-picking curves (choosing time windows that look most exponential) and ignoring bottlenecks like energy constraints, data limits, latency, regulation, or the difficulty of turning narrow competence into general competence. These don’t end forecasting—but they do widen the error bars.

Long-range AGI timelines—Kurzweil’s included—depend less on a single “breakthrough moment” and more on a stack of assumptions that all need to hold at once. If any layer weakens, the date can slide even if progress continues.

Most decades-ahead forecasts assume three curves rise together:

A key hidden assumption: these three drivers don’t substitute perfectly. If data quality plateaus, “just add compute” may deliver smaller returns.

Forecasts often treat compute as a smooth curve, but reality runs through factories and power grids.

Energy costs, chip manufacturing capacity, export controls, memory bandwidth, networking gear, and supply-chain shocks can all limit how fast training and deployment scale. Even if theory says “10× more compute,” the path there may be bumpy and expensive.

Decades-ahead predictions also assume society doesn’t slow adoption too much:

Regulation, liability, public trust, workplace integration, and ROI all influence whether advanced systems are trained and widely used—or kept in narrow, high-friction settings.

Perhaps the biggest assumption is that capability improvements from scaling (better reasoning, planning, tool use) naturally converge toward general intelligence.

“More compute” can produce models that are more fluent and useful, but not automatically more general in the sense of reliable transfer across domains, long-horizon autonomy, or stable goals. Long timelines often assume these gaps are engineering problems—not fundamental barriers.

Even if computing power and model sizes keep climbing, AGI could still arrive later than forecast for reasons that have little to do with raw speed. Several bottlenecks are about what we’re building and how we know it works.

“AGI” isn’t a single feature you can toggle on. A useful definition usually implies an agent that can learn new tasks quickly, transfer skills across domains, plan over long horizons, and handle messy, changing goals with high reliability.

If the target keeps shifting—chatty assistant vs. autonomous worker vs. scientist-level reasoner—then progress can look impressive while still missing key abilities like long-term memory, causal reasoning, or consistent decision-making.

Benchmarks can be gamed, overfit, or become obsolete. Skeptics typically want evidence that an AI can succeed on unseen tasks, under novel constraints, with low error rates and repeatable results.

If the field can’t agree on tests that convincingly separate “excellent pattern completion” from “general competence,” timelines become guesswork—and caution can slow deployment.

Capability can increase faster than controllability. If systems become more agentic, the bar rises for preventing deception, goal drift, and harmful side effects.

Regulation, audits, and safety engineering may add time even if the underlying models improve quickly—especially for high-stakes uses.

Many definitions of AGI implicitly assume competence in the physical world: manipulating objects, conducting experiments, operating tools, and adapting to real-time feedback.

If real-world learning proves data-hungry, slow, or risky, AGI could stall at “brilliant on-screen” performance—while practical generality waits on better robotics, simulation, and safe training methods.

Kurzweil’s forecasts are influential partly because they’re clear and quantitative—but that same clarity invites sharp critique.

A common objection is that Kurzweil leans heavily on extending historical curves (compute, storage, bandwidth) into the future. Critics argue that technology doesn’t always scale smoothly: chip progress can slow, energy costs can bite, and economic incentives can shift. Even if the long-term direction is upward, the rate can change in ways that make specific dates unreliable.

AGI isn’t only a matter of faster hardware. It’s a complex-systems problem involving algorithms, data, training methods, evaluation, safety constraints, and human adoption. Breakthroughs can be bottlenecked by a single missing idea—something you can’t reliably “calendar.” Skeptics point out that science often advances through uneven steps: long plateaus followed by sudden leaps.

Another critique is psychological: we remember dramatic correct calls more than the quieter misses or near-misses. If someone makes many strong predictions, a few memorable hits can dominate public perception. This doesn’t mean the forecaster is “wrong,” but it can inflate confidence in the exactness of timelines.

Even experts who accept rapid AI progress differ on what “counts” as AGI, what capabilities must generalize, and how to measure them. Small definitional differences (task breadth, autonomy, reliability, real-world learning) can shift forecasts by decades—without anyone changing their underlying view of current progress.

Kurzweil is one loud voice, but AGI timelines are a crowded debate. A useful way to map it is the near-term camp (AGI in years to a couple of decades) versus the long-term camp (multiple decades or “not this century”). They often look at the same trends but disagree on what’s missing: near-term forecasters emphasize rapid scaling and emergent capabilities, while long-term forecasters emphasize unsolved problems like reliable reasoning, autonomy, and real-world robustness.

Expert surveys aggregate beliefs from researchers and practitioners (for example, polls asking when there’s a 50% chance of “human-level AI”). These can reveal shifting sentiment over time, but they also reflect who was surveyed and how questions were framed.

Scenario planning avoids picking a single date. Instead, it sketches multiple plausible futures (fast progress, slow progress, regulatory bottlenecks, hardware constraints) and asks what signals would indicate each path.

Benchmark- and capability-based forecasting tracks concrete milestones (coding tasks, scientific reasoning, agent reliability) and estimates what rate of improvement would be needed to reach broader competence.

“AGI” might mean passing a broad test suite, doing most jobs, operating as an autonomous agent, or matching humans across domains with minimal supervision. A stricter definition generally pushes timelines later, and disagreement here explains a surprising amount of the spread.

Even optimistic and skeptical experts tend to agree on one point: timelines are highly uncertain, and forecasts should be treated as ranges with assumptions—not calendar commitments.

Forecasts about AGI can feel abstract, so it helps to track concrete signals that should move before any “big moment.” If Kurzweil-style timelines are directionally right, the next decade should show steady gains across capability, reliability, economics, and governance.

Watch for models that reliably plan across many steps, adapt when plans fail, and use tools (code, browsers, data apps) without constant hand-holding. The most meaningful sign isn’t a flashy demo—it’s autonomy with clear boundaries: agents that can complete multi-hour tasks, ask clarifying questions, and hand off work safely when uncertain.

Progress will look like lower error rates in realistic workflows, not just higher benchmark scores. Track whether “hallucinations” drop when systems are required to cite sources, run checks, or self-verify. A key milestone: strong performance under audit conditions—same task, multiple runs, consistent outcomes.

Look for measurable productivity gains in specific roles (support, analysis, software, operations), alongside new job categories built around supervising and integrating AI. Costs matter too: if high-quality output gets cheaper (per task, per hour), adoption accelerates—especially for small teams.

If capability rises, governance should move from principles to practice: standards, third-party audits, incident reporting, and regulation that clarifies liability. Also watch compute monitoring and reporting rules—signals that governments and industry treat scaling as a trackable, controllable lever.

If you want to use these signals without overreacting to headlines, see /blog/ai-progress-indicators.

AGI timelines are best treated like weather forecasts for a faraway date: useful for planning, unreliable as a promise. Kurzweil-style predictions can help you notice long-term trends and pressure-test decisions, but they shouldn’t be the single point of failure in your strategy.

Use forecasts to explore ranges and scenarios, not a single year. If someone says “AGI by 203X,” translate that into: “What changes would have to happen for that to be true—and what if they don’t?” Then plan for multiple outcomes.

For individuals: build durable skills (problem framing, domain expertise, communication) and keep a habit of learning new tools.

For businesses: invest in AI literacy, data quality, and pilot projects with clear ROI—while keeping a “no regrets” plan that works even if AGI arrives later.

One pragmatic way to operationalize “watch the signals and iterate” is to shorten build cycles: prototype workflows, test reliability, and quantify productivity gains before making large bets. Platforms like Koder.ai fit this approach by letting teams create web, backend, and mobile apps through a chat interface (with planning mode, snapshots, and rollback), so you can trial agent-assisted processes quickly, export source code when needed, and avoid locking strategy to a single forecast.

A balanced conclusion: timelines can guide preparation, not certainty. Use them to prioritize experiments and reduce blind spots—then revisit your assumptions regularly as new evidence arrives.

Kurzweil’s forecasts matter because they’re specific enough to test and widely cited, which shapes how people talk about AGI timelines.

Practically, they influence:

Even if the dates are wrong, the milestones and assumptions he highlights can be useful planning inputs.

In this context, AGI means an AI that can learn and perform a wide range of tasks at roughly human level, including adapting to new problems without being narrowly specialized.

A practical checklist implied by the article includes:

Kurzweil’s most discussed public view places human-level AGI in the late 2020s to 2030s, framed as a likely window rather than a guaranteed single year.

The actionable way to use this is to treat it as a scenario range and track whether the prerequisite trends (compute cost, algorithms, deployment) keep moving in the needed direction.

He argues that progress accelerates because improvements in a technology often make it easier to improve it again—creating a compounding feedback loop.

In practice, he points to trends like:

The core claim isn’t “one law explains everything,” but that compounding can make slow-looking early progress turn into rapid change later.

Compute is a key input, but the article emphasizes that hardware progress ≠ capability progress.

More compute helps when paired with:

A good mental model is: hardware is the ; capability is the —the mapping between them can change.

Useful supporting data includes long-run, measurable curves:

Key limits:

Major assumptions called out in the article include:

If any layer weakens, the date can slip even if progress continues.

Several delay factors don’t require trends to reverse:

These can slow timelines even while models keep improving on paper.

The article highlights critiques such as:

A practical takeaway: treat precise dates as , not promises.

Watch signals that move before any “AGI moment,” especially:

Using signals like these helps you update beliefs without overreacting to flashy demos.