Dec 02, 2025·8 min

React mental models: Dan Abramov style ways to think

React mental models can make React feel simple: learn the key ideas behind components, rendering, state, and effects, then apply them to build UI fast via chat.

React mental models can make React feel simple: learn the key ideas behind components, rendering, state, and effects, then apply them to build UI fast via chat.

React can feel frustrating at first because you can see the UI change, but you can’t always explain why it changed. You click a button, something updates, and then a different part of the page surprises you. That’s usually not “React is weird.” It’s “my picture of what React is doing is fuzzy.”

A mental model is the simple story you tell yourself about how something works. If the story is wrong, you’ll make confident decisions that lead to confusing results. Think about a thermostat: a bad model is “I set 22°C, so the room becomes 22°C instantly.” A better model is “I set a target, and the heater turns on and off over time to reach it.” With the better story, the behavior stops feeling random.

React works the same way. Once you adopt a few clear ideas, React becomes predictable: you can look at the current data and reliably guess what will be on screen.

Dan Abramov helped popularize this “make it predictable” mindset. The goal isn’t to memorize rules. It’s to keep a small set of truths in your head so you can debug by reasoning, not by trial and error.

Keep these ideas in view:

Hold onto those and React stops feeling like magic. It starts feeling like a system you can trust.

React gets easier when you stop thinking in “screens” and start thinking in small pieces. A component is a reusable unit of UI. It takes inputs and returns a description of what the UI should look like for those inputs.

It helps to treat a component as a pure description: “given this data, show this.” That description can be used in many places because it doesn’t depend on where it lives.

Props are the inputs. They come from a parent component. Props aren’t “owned” by the component, and they aren’t something the component should quietly change. If a button receives label="Save", the button’s job is to render that label, not to decide it should be different.

State is owned data. It’s what the component remembers over time. State changes when a user interacts, when a request finishes, or when you decide something should be different. Unlike props, state belongs to that component (or to whichever component you choose to own it).

Plain version of the key idea: UI is a function of state. If state says “loading,” show a spinner. If state says “error,” show a message. If state says “items = 3,” render three rows. Your job is to keep the UI reading from state, not drifting into hidden variables.

A quick way to separate the concepts is:

SearchBox, ProfileCard, CheckoutForm)name, price, disabled)isOpen, query, selectedId)Example: a modal. The parent can pass title and onClose as props. The modal might own isAnimating as state.

Even if you’re generating UI through chat (for example on Koder.ai), this separation is still the fastest way to stay sane: decide what’s props vs state first, then let the UI follow.

A useful way to hold React in your head (very Dan Abramov in spirit) is: rendering is a calculation, not a paint job. React runs your component functions to figure out what the UI should look like for the current props and state. The output is a UI description, not pixels.

A re-render just means React repeats that calculation. It doesn’t mean “the whole page redraws.” React compares the new result to the previous one and applies the smallest set of changes to the real DOM. Many components can re-render while only a few DOM nodes actually update.

Most re-renders happen for a few simple reasons: a component’s state changed, its props changed, or a parent re-rendered and React asked the child to render again. That last one surprises people, but it’s usually fine. If you treat render as “cheap and boring,” your app stays easier to reason about.

The rule of thumb that keeps this clean: make render pure. Given the same inputs (props + state), your component should return the same UI description. Keep surprises out of render.

Concrete example: if you generate an ID with Math.random() inside render, a re-render changes it and suddenly a checkbox loses focus or a list item remounts. Create the ID once (state, memo, or outside the component) and render becomes stable.

If you remember one sentence: a re-render means “recompute what the UI should be,” not “rebuild everything.”

Another helpful model: state updates are requests, not instant assignments. When you call a setter like setCount(count + 1), you’re asking React to schedule a render with a new value. If you read state right after, you might still see the old value because React hasn’t rendered yet.

That’s why “small and predictable” updates matter. Prefer describing the change instead of grabbing whatever you think the current value is. When the next value depends on the previous one, use the updater form: setCount(c => c + 1). It matches how React works: multiple updates can be queued, then applied in order.

Immutability is the other half of the picture. Don’t change objects and arrays in place. Create a new one with the change. React can then see “this value is new,” and your brain can trace what changed.

Example: toggling a todo item. The safe approach is to create a new array and a new todo object for the one item you changed. The risky approach is flipping todo.done = !todo.done inside the existing array.

Also keep state minimal. A common trap is storing values you can calculate. If you already have items and filter, don’t store filteredItems in state. Calculate it during render. Fewer state variables means fewer ways for values to drift out of sync.

A simple test for what belongs in state:

If you’re building UI via chat (including on Koder.ai), ask for changes as tiny patches: “Add one boolean flag” or “Update this list immutably.” Small, explicit changes keep the generator and your React code aligned.

Rendering describes UI. Effects sync with the outside world. “Outside” means things React doesn’t control: network calls, timers, browser APIs, and sometimes imperative DOM work.

If something can be calculated from props and state, it usually shouldn’t live in an effect. Putting it in an effect adds a second step (render, run effect, set state, render again). That extra hop is where flickers, loops, and “why is this stale?” bugs show up.

A common confusion: you have firstName and lastName, and you store fullName in state using an effect. But fullName isn’t a side effect. It’s derived data. Compute it during render and it will always match.

As a habit: derive UI values during render (or with useMemo when something is truly expensive), and use effects for “do something” work, not “figure something out” work.

Treat the dependency array as: “When these values change, re-sync with the outside world.” It’s not a performance trick and it’s not a place to silence warnings.

Example: if you fetch user details when userId changes, userId belongs in the dependency array because it should trigger the sync. If the effect uses token too, include it, or you might fetch with an old token.

A good gut check: if removing an effect would only make the UI wrong, it probably wasn’t a real effect. If removing it would stop a timer, cancel a subscription, or skip a fetch, it probably was.

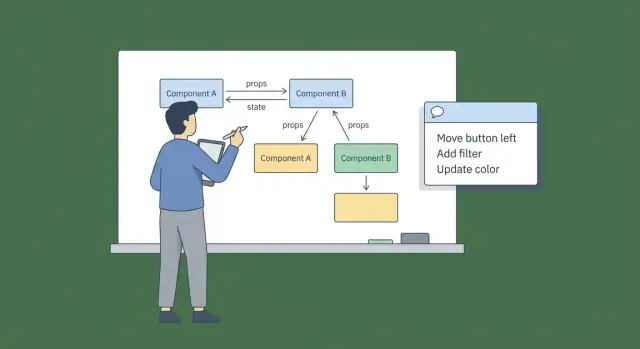

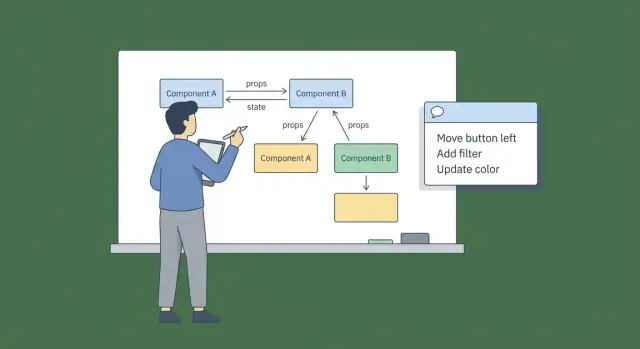

One of the most useful mental models is simple: data goes down the tree, and user actions go up.

A parent passes values to children. Children shouldn’t secretly “own” the same value in two places. They request changes by calling a function, and the parent decides what the new value is.

When two parts of the UI need to agree, pick one place to store the value, then pass it down. This is “lifting state.” It can feel like extra plumbing, but it prevents a worse problem: two states that drift apart and force you to add hacks to keep them in sync.

Example: a search box and a results list. If the input stores its own query and the list stores its own query, you’ll eventually see “input shows X but list uses Y.” The fix is to keep query in one parent, pass it to both, and pass an onChangeQuery(newValue) handler back to the input.

Lifting state isn’t always the answer. If a value only matters inside one component, keep it there. Keeping state close to where it’s used usually makes code easier to read.

A practical boundary:

If you’re unsure whether to lift state, look for signals like: two components show the same value in different ways; an action in one place must update something far away; you keep copying props into state “just in case”; or you’re adding effects only to keep two values aligned.

This model also helps when building via chat tools like Koder.ai: ask for a single owner for each piece of shared state, then generate handlers that flow upward.

Pick a feature small enough to hold in your head. A good one is a searchable list where you can click an item to see details in a modal.

Start by sketching the UI parts and the events that can happen. Don’t think about code yet. Think about what the user can do and what they can see: there’s a search input, a list, a selected row highlight, and a modal. The events are typing in search, clicking an item, opening the modal, and closing the modal.

Now “draw the state.” Write down the few values that must be stored, and decide who owns them. A simple rule works well: the closest common parent of all places that need a value should own it.

For this feature, stored state can be tiny: query (string), selectedId (id or null), and isModalOpen (boolean). The list reads query and renders items. The modal reads selectedId to show details. If both list and modal need selectedId, keep it in the parent, not in both.

Next, separate derived data from stored data. The filtered list is derived: filteredItems = items.filter(...). Don’t store it in state because it can always be recomputed from items and query. Storing derived data is how values drift apart.

Only then ask: do we need an effect? If items are already in memory, no. If typing a query should fetch results, yes. If closing the modal should save something, yes. Effects are for syncing (fetch, save, subscribe), not for basic UI wiring.

Finally, test the flow with a few edge cases:

selectedId still valid?If you can answer those on paper, the React code is usually straightforward.

Most React confusion isn’t about syntax. It happens when your code stops matching the simple story in your head.

Storing derived state. You save fullName in state even though it’s just firstName + lastName. It works until one field changes and the other doesn’t, and the UI shows a stale value.

Effect loops. An effect fetches data, sets state, and the dependency list makes it run again. The symptom is repeated requests, jittery UI, or state that never settles.

Stale closures. A click handler reads an old value (like an outdated counter or filter). The symptom is “I clicked, but it used yesterday’s value.”

Global state everywhere. Putting every UI detail into a global store makes it hard to tell what owns what. The symptom is you change one thing and three screens react in surprising ways.

Mutating nested objects. You update an object or array in place and wonder why the UI didn’t update. The symptom is “the data changed, but nothing re-rendered.”

Here’s a concrete example: a “search and sort” panel for a list. If you store filteredItems in state, it can drift from items when new data arrives. Instead, store the inputs (search text, sort choice) and compute the filtered list during render.

With effects, keep them for syncing with the outside world (fetching, subscriptions, timers). If an effect is doing basic UI work, it often belongs in render or an event handler.

When generating or editing code via chat, these mistakes show up faster because changes can arrive in big chunks. A good habit is to frame requests in terms of ownership: “What is the source of truth for this value?” and “Can we compute this instead of storing it?”

When your UI starts to feel unpredictable, it’s rarely “too much React.” It’s usually too much state, in the wrong places, doing jobs it shouldn’t do.

Before you add another useState, pause and ask:

Small example: search box, filter dropdown, list. If you store both query and filteredItems in state, you now have two sources of truth. Instead, keep query and filter as state, then derive filteredItems during render from the full list.

This matters when you build quickly via chat tools too. Speed is great, but keep asking: “Did we add state, or did we add a derived value by accident?” If it’s derived, delete that state and compute it.

A small team is building an admin UI: a table of orders, a few filters, and a dialog to edit an order. The first request is vague: “Add filters and an edit popup.” That sounds simple, but it often turns into random state sprinkled everywhere.

Make it concrete by translating the request into state and events. Instead of “filters,” name the state: query, status, dateRange. Instead of “edit popup,” name the event: “user clicks Edit on a row.” Then decide who owns each piece of state (page, table, or dialog) and what can be derived (like a filtered list).

Example prompts that keep the model intact (these also work well in chat-based builders like Koder.ai):

OrdersPage that owns filters and selectedOrderId. OrdersTable is controlled by filters and calls onEdit(orderId).”visibleOrders from orders and filters. Do not store visibleOrders in state.”EditOrderDialog that receives order and open. When saved, call onSave(updatedOrder) and close.”filters to the URL, not to compute filtered rows.”After the UI is generated or updated, review changes with a quick check: each state value has one owner, derived values aren’t stored, effects are only syncing with the outside world (URL, network, storage), and events flow down as props and up as callbacks.

When state is predictable, iteration feels safe. You can change the table layout, add a new filter, or tweak the dialog fields without guessing which hidden state will break next.

Speed is only useful if the app stays easy to reason about. The simplest protection is to treat these mental models like a checklist you apply before you write (or generate) UI.

Start each feature the same way: write down the state you need, the events that can change it, and who owns it. If you can’t say, “This component owns this state, and these events update it,” you’ll probably end up with scattered state and surprising re-renders.

If you’re building through chat, start with planning mode. Describe the components, the state shape, and the transitions in plain language before asking for code. For example: “A filter panel updates query state; the results list derives from query; selecting an item sets selectedId; closing clears it.” Once that reads cleanly, generating the UI becomes a mechanical step.

If you’re using Koder.ai (koder.ai) to generate React code, it’s worth doing a quick sanity pass before moving on: one clear owner for each state value, UI derived from state, effects only for syncing, and no duplicate sources of truth.

Then iterate in small steps. If you want to change the state structure (say, from several booleans to a single status field), take a snapshot first, experiment, and roll back if the mental model got worse. And when you need a deeper review or a handoff, exporting the source code makes it easier to answer the real question: does the state shape still tell the story of the UI?

A good starting model is: UI = f(state, props). Your components don’t “edit the DOM”; they describe what should be on screen for the current data. If the screen looks wrong, inspect the state/props that produced it, not the DOM.

Props are inputs from a parent; your component should treat them as read-only. State is memory owned by a component (or whichever component you choose as the owner). If a value must be shared, lift it up and pass it down as props.

A re-render means React re-runs your component function to compute the next UI description. It doesn’t automatically mean the whole page is repainted. React then updates the real DOM with the smallest changes it needs.

Because state updates are scheduled, not immediate assignments. If the next value depends on the previous one, use the updater form so you don’t rely on a possibly stale value:

setCount(c => c + 1)This stays correct even if multiple updates are queued.

Avoid storing anything you can compute from existing inputs. Store the inputs, derive the rest during render.

Examples:

items, filtervisibleItems = items.filter(...)This prevents values drifting out of sync.

Use effects to sync with things React doesn’t control: fetching, subscriptions, timers, browser APIs, or imperative DOM work.

Don’t use an effect just to compute UI values from state—compute those during render (or with useMemo if it’s expensive).

Treat dependencies as a trigger list: “when these values change, re-sync.” Include every reactive value your effect reads.

If you leave something out, you risk stale data (like an old userId or token). If you add the wrong things, you can create loops—often a sign the effect is doing work that belongs in events or render.

If two parts of the UI must always agree, put the state in their closest common parent, pass the value down, and pass callbacks up.

A quick test: if you’re duplicating the same value in two components and writing effects to “keep them in sync,” that state probably needs a single owner.

It usually happens when a handler “captures” an old value from a previous render. Common fixes:

setX(prev => ...)If a click uses “yesterday’s value,” suspect a stale closure.

Start with a small plan: components, state owners, and events. Then generate code as tiny patches (add one state field, add one handler, derive one value) instead of large rewrites.

If you use a chat builder like Koder.ai, ask for:

That keeps the generated code aligned with React’s mental model.