Oct 10, 2025·8 min

Redis for Your Applications: Patterns, Pitfalls, and Tips

Learn practical ways to use Redis in your apps: caching, sessions, queues, pub/sub, and rate limiting—plus scaling, persistence, monitoring, and pitfalls.

Learn practical ways to use Redis in your apps: caching, sessions, queues, pub/sub, and rate limiting—plus scaling, persistence, monitoring, and pitfalls.

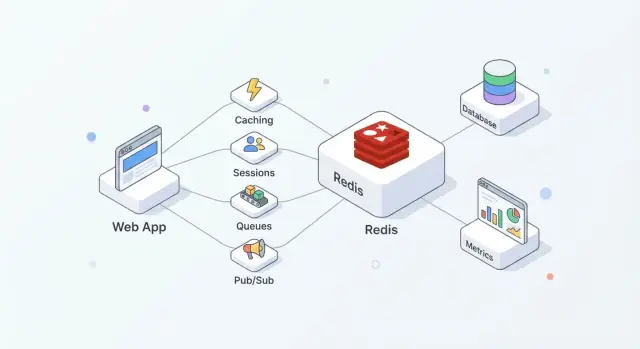

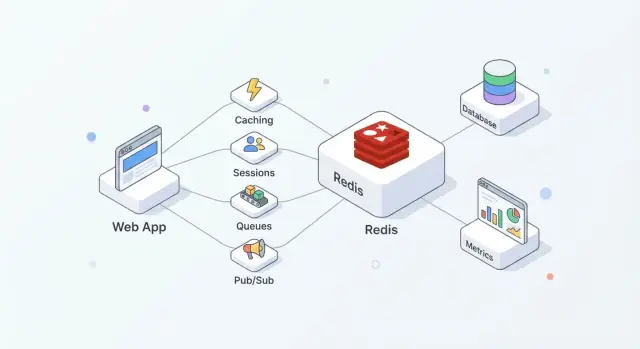

Redis is an in-memory data store often used as a shared “fast layer” for applications. Teams like it because it’s straightforward to adopt, extremely quick for common operations, and flexible enough to handle more than one job (cache, sessions, counters, queues, pub/sub) without introducing a brand-new system for each.

In practice, Redis works best when you treat it as speed + coordination, while your primary database remains the source of truth.

A common setup looks like this:

This split keeps your database focused on correctness and durability, while Redis absorbs high-frequency reads/writes that would otherwise drive up latency or load.

Used well, Redis tends to deliver a few practical outcomes:

Redis is not a replacement for a primary database. If you need complex queries, long-term storage guarantees, or analytics-style reporting, your database is still the right home.

Also, don’t assume Redis is “durable by default.” If losing even a few seconds of data is unacceptable, you’ll need careful persistence settings—or a different system—based on your real recovery requirements.

Redis is often described as a “key-value store,” but it’s more useful to think of it as a very fast server that can hold and manipulate small pieces of data by name (the key). That model encourages predictable access patterns: you typically know exactly what you want (a session, a cached page, a counter), and Redis can fetch or update it in a single round trip.

Redis keeps data in RAM, which is why it can respond in microseconds to low milliseconds. The trade-off is that RAM is limited and more expensive than disk.

Decide early whether Redis is:

Redis can persist data to disk (RDB snapshots and/or AOF append-only logs), but persistence adds write overhead and forces durability choices (for example, “fast but may lose a second” vs “slower but safer”). Treat persistence as a dial you set based on business impact, not a box you automatically tick.

Redis executes commands mostly in a single thread, which sounds limiting until you remember two things: operations are typically small, and there’s no locking overhead between multiple worker threads. As long as you avoid expensive commands and oversized payloads, this model can be extremely efficient under high concurrency.

Your app talks to Redis over TCP using client libraries. Use connection pooling, keep requests small, and prefer batching/pipelining when you need multiple operations.

Plan for timeouts and retries: Redis is fast, but networks aren’t, and your application should degrade gracefully when Redis is busy or temporarily unavailable.

If you’re building a new service and want to standardize these basics quickly, a platform like Koder.ai can help you scaffold a React + Go + PostgreSQL application and then add Redis-backed features (caching, sessions, rate limiting) through a chat-driven workflow—while still letting you export the source code and run it wherever you need.

Caching only helps when it has clear ownership: who fills it, who invalidates it, and what “good enough” freshness means.

Cache-aside means your application—not Redis—controls reads and writes.

Typical flow:

Redis is a fast key-value store; your app decides how to serialize, version, and expire entries.

A TTL is a product decision as much as a technical one. Short TTLs reduce staleness but increase database load; long TTLs save work but risk outdated results.

Practical tips:

user:v3:123) so old cached shapes don’t break new code.When a hot key expires, many requests can miss at once.

Common defenses:

Good candidates include API responses, expensive query results, and computed objects (recommendations, aggregations). Caching full HTML pages can work, but be careful with personalization and permissions—cache fragments when user-specific logic is involved.

Redis is a practical place to keep short-lived login state: session IDs, refresh-token metadata, and “remember this device” flags. The goal is to make authentication fast while keeping session lifetime and revocation under tight control.

A common pattern is: your app issues a random session ID, stores a compact record in Redis, and returns the ID to the browser as an HTTP-only cookie. On each request, you look up the session key and attach the user identity and permissions to the request context.

Redis works well here because session reads are frequent, and session expiration is built-in.

Design keys so they’re easy to scan and revoke:

sess:{sessionId} → session payload (userId, issuedAt, deviceId)user:sessions:{userId} → a Set of active session IDs (optional, for “log out everywhere”)Use a TTL on sess:{sessionId} that matches your session lifetime. If you rotate sessions (recommended), create a new session ID and delete the old one immediately.

Be careful with “sliding expiration” (extending TTL on every request): it can keep sessions alive indefinitely for heavy users. A safer compromise is extending TTL only when it’s close to expiring.

To log out a single device, delete sess:{sessionId}.

To log out across devices, either:

user:sessions:{userId}, oruser:revoked_after:{userId} timestamp and treat any session issued before it as invalidThe timestamp method avoids large fan-out deletes.

Store the minimum needed in Redis—prefer IDs over personal data. Never store raw passwords or long-lived secrets. If you must store token-related data, store hashes and use tight TTLs.

Limit who can connect to Redis, require authentication, and keep session IDs high-entropy to prevent guessing attacks.

Rate limiting is where Redis shines: it’s fast, shared across your app instances, and offers atomic operations that keep counters consistent under heavy traffic. It’s useful for protecting login endpoints, expensive searches, password reset flows, and any API that can be scraped or brute-forced.

Fixed window is the simplest: “100 requests per minute.” You count requests in the current minute bucket. It’s easy, but can allow bursts at the boundary (e.g., 100 at 12:00:59 and 100 at 12:01:00).

Sliding window smooths boundaries by looking at the last N seconds/minutes rather than the current bucket. It’s fairer, but typically costs more (you may need sorted sets or more bookkeeping).

Token bucket is great for burst handling. Users “earn” tokens over time up to a cap; each request spends one token. This allows short bursts while still enforcing an average rate.

A common fixed-window pattern is:

INCR key to increment a counterEXPIRE key window_seconds to set/reset the TTLThe trick is doing it safely. If you run INCR and EXPIRE as separate calls, a crash between them can create keys that never expire.

Safer approaches include:

INCR and set EXPIRE only when the counter is first created.SET key 1 EX <ttl> NX for initialization, then INCR after (often still wrapped in a script to avoid races).Atomic operations matter most when traffic spikes: without them, two requests can “see” the same remaining quota and both pass.

Most apps need multiple layers:

rl:user:{userId}:{route})For bursty endpoints, token bucket (or a generous fixed window plus a short “burst” window) helps avoid punishing legitimate spikes like page loads or mobile reconnects.

Decide upfront what “safe” means:

A common compromise is fail-open for low-risk routes and fail-closed for sensitive ones (login, password reset, OTP), with monitoring so you notice the moment rate limiting stops working.

Redis can power background jobs when you need a lightweight queue for sending emails, resizing images, syncing data, or running periodic tasks. The key is choosing the right data structure and setting clear rules for retries and failure handling.

Lists are the simplest queue: producers LPUSH, workers BRPOP. They’re easy, but you’ll need extra logic for “in-flight” jobs, retries, and visibility timeouts.

Sorted sets shine when scheduling matters. Use the score as a timestamp (or priority), and workers fetch the next due job. This fits delayed jobs and priority queues.

Streams are often the best default for durable work distribution. They support consumer groups, keep a history, and let multiple workers coordinate without inventing your own “processing list.”

With Streams consumer groups, a worker reads a message and later ACKs it. If a worker crashes, the message stays pending and can be claimed by another worker.

For retries, track attempt counts (in the message payload or a side key) and apply exponential backoff (often via a sorted set “retry schedule”). After a max attempt limit, move the job to a dead-letter queue (another stream or list) for manual review.

Assume jobs can run twice. Make handlers idempotent by:

job:{id}:done) with SET ... NX before side effectsKeep payloads small (store big data elsewhere and pass references). Add backpressure by limiting queue length, slowing producers when lag grows, and scaling workers based on pending depth and processing time.

Redis Pub/Sub is the simplest way to broadcast events: publishers send a message to a channel, and every connected subscriber gets it immediately. There’s no polling—just a lightweight “push” that works well for real-time updates.

Pub/Sub shines when you care about speed and fan-out more than guaranteed delivery:

A useful mental model: Pub/Sub is like a radio station. Anyone tuned in hears the broadcast, but nobody gets a recording automatically.

Pub/Sub has important trade-offs:

Because of this, Pub/Sub is a poor fit for workflows where every event must be processed (exactly once—or even at least once).

If you need durability, retries, consumer groups, or backpressure handling, Redis Streams are usually a better choice. Streams let you store events, process them with acknowledgements, and recover after restarts—much closer to a lightweight message queue.

In real deployments you’ll have multiple app instances subscribing. A few practical tips:

app:{env}:{domain}:{event} (e.g., shop:prod:orders:created).notifications:global, and target users with notifications:user:{id}.Used this way, Pub/Sub is a fast event “signal,” while Streams (or another queue) handles events you can’t afford to lose.

Choosing a Redis data structure isn’t just about “what works”—it affects memory use, query speed, and how simple your code stays over time. A good rule is to pick the structure that matches the questions you’ll ask later (read patterns), not just how you store the data today.

INCR/DECR.SISMEMBER and easy set operations.Redis operations are atomic at the command level, so you can safely increment counters without race conditions. Page views and rate-limit counters typically use strings with INCR plus an expiry.

Leaderboards are where sorted sets shine: you can update scores (ZINCRBY) and fetch the top players (ZREVRANGE) efficiently, without scanning all entries.

If you create many keys like user:123:name, user:123:email, user:123:plan, you multiply metadata overhead and make key management harder.

A hash like user:123 with fields (name, email, plan) keeps related data together and typically reduces key count. It also makes partial updates straightforward (update one field rather than rewriting an entire JSON string).

When in doubt, model a small sample and measure memory usage before committing to a structure for high-volume data.

Redis is often described as “in-memory,” but you still get choices for what happens when a node restarts, a disk fills up, or a server disappears. The right setup depends on how much data you can afford to lose and how quickly you need to recover.

RDB snapshots save a point-in-time dump of your dataset. They’re compact and fast to load on startup, which can make restarts quicker. The trade-off is that you can lose the most recent writes since the last snapshot.

AOF (append-only file) logs write operations as they happen. This typically reduces potential data loss because changes are recorded more continuously. AOF files can grow larger, and replays during startup can take longer—though Redis can rewrite/compact the AOF to keep it manageable.

Many teams run both: snapshots for faster restarts, plus AOF for better write durability.

Persistence isn’t free. Disk writes, AOF fsync policies, and background rewrite operations can add latency spikes if your storage is slow or saturated. On the other hand, persistence makes restarts less scary: with no persistence, an unplanned restart means an empty Redis.

Replication keeps a copy (or copies) of data on replicas so you can fail over when the primary goes down. The goal is usually availability first, not perfect consistency. Under failure, replicas may be slightly behind, and a failover can lose the last acknowledged writes in some scenarios.

Before tuning anything, write down two numbers:

Use those targets to pick RDB frequency, AOF settings, and whether you need replicas (and automated failover) for your Redis role—cache, session store, queue, or primary data store.

A single Redis node can take you surprisingly far: it’s simple to operate, easy to reason about, and often fast enough for many caching, session, or queue workloads.

Scaling becomes necessary when you hit hard limits—usually memory ceiling, CPU saturation, or a single node becoming a single point of failure you can’t accept.

Consider adding more nodes when one (or more) of these is true:

A practical first step is often separating workloads (two independent Redis instances) before jumping into a cluster.

Sharding means splitting your keys across multiple Redis nodes so each node stores only a portion of the data. Redis Cluster is Redis’s built-in way to do this automatically: the keyspace is divided into slots, and each node owns some of those slots.

The win is more total memory and more aggregate throughput. The tradeoff is added complexity: multi-key operations become constrained (keys must be on the same shard), and troubleshooting involves more moving parts.

Even with “even” sharding, real traffic can be lopsided. A single popular key (a “hot key”) can overload one node while others sit idle.

Mitigations include adding short TTLs with jitter, splitting the value across multiple keys (key hashing), or redesigning access patterns so reads spread out.

A Redis Cluster requires a cluster-aware client that can discover the topology, route requests to the right node, and follow redirections when slots move.

Before migrating, confirm:

Scaling works best when it’s a planned evolution: validate with load tests, instrument key latency, and migrate traffic gradually rather than flipping everything at once.

Redis is often treated as “internal plumbing,” which is exactly why it’s a frequent target: a single exposed port can turn into a full data leak or an attacker-controlled cache. Assume Redis is sensitive infrastructure, even if you only store “temporary” data.

Start by enabling authentication and using ACLs (Redis 6+). ACLs let you:

Avoid sharing one password across every component. Instead, issue per-service credentials and keep permissions narrow.

The most effective control is not being reachable. Bind Redis to a private interface, place it on a private subnet, and restrict inbound traffic with security groups/firewalls to only the services that need it.

Use TLS when Redis traffic crosses host boundaries you don’t fully control (multi-AZ, shared networks, Kubernetes nodes, or hybrid environments). TLS prevents sniffing and credential theft, and it’s worth the small overhead for sessions, tokens, or any user-related data.

Lock down commands that can cause major damage if abused. Common examples to disable or restrict via ACLs: FLUSHALL, FLUSHDB, CONFIG, SAVE, DEBUG, and EVAL (or at least control scripting carefully). Also protect the rename-command approach with care—ACLs are usually clearer and easier to audit.

Store Redis credentials in your secrets manager (not in code or container images), and plan for rotation. Rotation is easiest when clients can reload credentials without a redeploy, or when you support two valid credentials during a transition window.

If you want a practical checklist, keep one in your runbooks alongside your /blog/monitoring-troubleshooting-redis notes.

Redis often “feels fine”… until traffic shifts, memory creeps up, or a slow command stalls everything. A lightweight monitoring routine and a clear incident checklist prevent most surprises.

Start with a small set you can explain to anyone on the team:

When something is “slow,” confirm it with Redis’s own tools:

KEYS, SMEMBERS, or large LRANGE calls is a common red flag.If latency jumps while CPU looks fine, also consider network saturation, oversized payloads, or blocked clients.

Plan for growth by keeping headroom (commonly 20–30% free memory) and revisiting assumptions after launches or feature flags. Treat “steady evictions” as an outage, not a warning.

During an incident, check (in order): memory/evictions, latency, client connections, slowlog, replication lag, and recent deploys. Write down the top recurring causes and fix them permanently—alerts alone won’t.

If your team is iterating quickly, it can help to bake these operational expectations into your development workflow. For example, with Koder.ai’s planning mode and snapshots/rollback, you can prototype Redis-backed features (like caching or rate limiting), test them under load, and revert changes safely—while keeping the implementation in your codebase via source export.

Redis is best as a shared, in-memory “fast layer” for:

Use your primary database for durable, authoritative data and complex queries. Treat Redis as an accelerator and coordinator, not your system of record.

No. Redis can persist, but it’s not “durable by default.” If you need complex querying, strong durability guarantees, or analytics/reporting, keep that data in your primary database.

If losing even a few seconds of data is unacceptable, don’t assume Redis persistence settings will meet that need without careful configuration (or consider a different system for that workload).

Decide based on your acceptable data loss and restart behavior:

Write down RPO/RTO targets first, then tune persistence to match them.

In cache-aside, your app owns the logic:

This works well when your application can tolerate occasional misses and you have a clear plan for expiration/invalidation.

Pick TTLs based on user impact and backend load:

user:v3:123) when the cached shape may change.If you’re unsure, start shorter, measure database load, then adjust.

Use one (or more) of these:

These patterns prevent synchronized cache misses from overloading your database.

A common approach is:

sess:{sessionId} with a TTL matching session lifetime.user:sessions:{userId} as a set of active session IDs for “log out everywhere.”Avoid extending TTL on every request (“sliding expiration”) unless you control it (e.g., only extend when close to expiring).

Use atomic updates so counters can’t get stuck or race:

INCR and EXPIRE as separate, unprotected calls.Scope keys thoughtfully (per-user, per-IP, per-route), and decide upfront whether to fail-open or fail-closed when Redis is unavailable—especially for sensitive endpoints like login.

Choose based on durability and operational needs:

LPUSH/BRPOP): simple, but you must build retries, in-flight tracking, and timeouts yourself.Use Pub/Sub for fast, real-time broadcasts where missing messages is acceptable (presence, live dashboards). It has:

If every event must be processed, prefer Redis Streams for durability, consumer groups, retries, and backpressure. For operational hygiene, also lock Redis down with ACLs/network isolation and track latency/evictions; keep a runbook like .

Keep job payloads small; store large blobs elsewhere and pass references.

/blog/monitoring-troubleshooting-redis