Dec 30, 2025·8 min

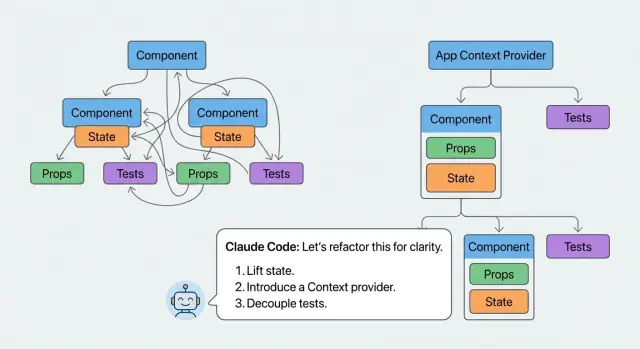

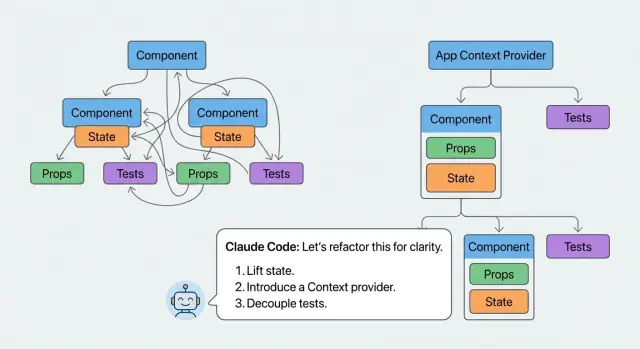

Refactoring React components with Claude Code safely

Learn refactoring React components with Claude Code using characterization tests, small safe steps, and state untangling to improve structure without changing behavior.

Learn refactoring React components with Claude Code using characterization tests, small safe steps, and state untangling to improve structure without changing behavior.

React refactors feel risky because most components aren’t small, clean building blocks. They’re living piles of UI, state, effects, and “just one more prop” fixes. When you change structure, you often change timing, identity, or data flow without meaning to.

A refactor changes behavior most often when it accidentally:

Refactors also turn into rewrites when “cleanup” gets mixed with “improvements.” You start by extracting a component, then rename a bunch of things, then “fix” the state shape, then replace a hook. Soon you’re changing logic while also changing layout. Without guardrails, it’s hard to know which change caused the bug.

A safe refactor has one simple promise: users get the same behavior, and you end up with clearer code. Props, events, loading states, error states, and edge cases should act the same. If behavior changes, it should be intentional, small, and clearly called out.

If you’re refactoring React components with Claude Code (or any coding assistant), treat it like a fast pair programmer, not an autopilot. Ask it to describe the risks before making edits, propose a plan with tiny steps, and explain how it checked that behavior stayed the same. Then validate yourself: run the app, click the weird paths, and lean on tests that capture what the component does today, not what you wish it did.

Pick one component that actively costs you time. Not the whole page, not “the UI layer,” and not a vague “cleanup.” Choose a single component that’s hard to read, hard to change, or full of fragile state and side effects. A tight target also makes assistant suggestions easier to verify.

Write a goal you can check in five minutes. Good goals are about structure, not outcomes: “split into smaller components,” “make state easier to follow,” or “make it testable without mocking half the app.” Avoid goals like “make it better” or “improve performance” unless you have a metric and a known bottleneck.

Set boundaries before you open the editor. The safest refactors are boring:

Then list the dependencies that can quietly break behavior when you move code around: API calls, context providers, routing params, feature flags, analytics events, and shared global state.

A concrete example: you have a 600-line OrdersTable that fetches data, filters it, manages selection, and shows a drawer with details. A clear goal could be: “extract row rendering and drawer UI into components, and move selection state into one reducer, with no UI changes.” That goal tells you what “done” looks like and what’s out of scope.

Before you refactor, treat the component like a black box. Your job is to capture what it does today, not what you wish it did. This keeps the refactor from turning into a redesign.

Start by writing the current behavior in plain language: given these inputs, the UI shows that output. Include props, URL params, feature flags, and any data that comes from context or a store. If you’re using Claude Code, paste a small, focused snippet and ask it to restate the behavior as precise sentences you can check later.

Cover the UI states people actually see. A component can look fine on the happy path while breaking the moment it hits loading, empty, or error.

Also capture the implicit rules that are easy to miss, and often cause refactors to break behavior:

Example: you have a user table that loads results, supports search, and sorts by “Last active.” Write down what happens when search is empty, when the API returns an empty list, when the API errors, and when two users have the same “Last active” time. Note small details like whether sorting is case-insensitive, and whether the table keeps the current page when a filter changes.

When your notes feel boring and specific, you’re ready.

Characterization tests are “this is what it does today” tests. They describe the current behavior, even when it’s weird, inconsistent, or clearly not what you want long-term. That sounds backwards, but it keeps a refactor from quietly turning into a rewrite.

When you’re refactoring React components with Claude Code, these tests are your safety rails. The tool can help reshape code, but you decide what must not change.

Focus on what users (and other code) depend on:

To keep tests stable, assert outcomes, not implementation. Prefer “the Save button becomes disabled and a message appears” over “setState was called” or “this hook ran.” If a test breaks because you renamed a component or reordered hooks, it wasn’t protecting behavior.

Async behavior is where refactors often change timing. Treat it explicitly: wait for the UI to settle, then assert. If there are timers (debounced search, delayed toasts), use fake timers and advance time. If there are network calls, mock fetch and assert what the user sees after success and after failure. For Suspense-like flows, test both the fallback and the resolved view.

Example: a “Users” table shows “No results” only after a search completes. A characterization test should lock that sequence in: loading indicator first, then either rows or the empty message, regardless of how you later split the component.

The win isn’t “bigger changes faster.” The win is getting a clear picture of what the component does, then changing one small thing at a time while keeping behavior stable.

Start by pasting the component and asking for a plain-English summary of its responsibilities. Push for specifics: what data it shows, what user actions it handles, and what side effects it triggers (fetching, timers, subscriptions, analytics). This often exposes the hidden jobs that make refactors risky.

Next, ask for a dependency map. You want an inventory of every input and output: props, context reads, custom hooks, local state, derived values, effects, and any module-level helpers. A useful map also calls out what’s safe to move (pure calculations) versus what’s “sticky” (timing, DOM, network).

Then ask it to propose extraction candidates, with one strict rule: separate pure view pieces from stateful controller pieces. JSX-heavy sections that only need props are great first extractions. Sections that mix event handlers, async calls, and state updates usually aren’t.

A workflow that holds up in real code:

Checkpoints matter. Ask Claude Code for a minimal plan where each step can be committed and reverted. A practical checkpoint might be: “Extract <TableHeader> with no logic changes” before touching sorting state.

Concrete example: if a component renders a customer table, controls filters, and fetches data, extract the table markup first (headers, rows, empty state) into a pure component. Only after that should you move filter state or the fetch effect. This order keeps bugs from traveling with the JSX.

When you split a big component, the risk isn’t moving JSX. The risk is accidentally changing data flow, timing, or event wiring. Treat extraction as a copy-and-wire exercise first, and a cleanup exercise later.

Start by spotting boundaries that already exist in the UI, not in your file structure. Look for parts you could describe as their own “thing” in a sentence: a header with actions, a filter bar, a results list, a footer with pagination.

A safe first move is to extract pure presentational components: props in, JSX out. Keep them boring on purpose. No new state, no new effects, no new API calls. If the original component had a click handler that did three things, keep that handler in the parent and pass it down.

Safe boundaries that usually work well include a header area, a list and row item, filters (inputs only), footer controls (pagination, totals, bulk actions), and dialogs (open/close and callbacks passed in).

Naming matters more than people think. Choose specific names like UsersTableHeader or InvoiceRowActions. Avoid grab-bag names like “Utils” or “HelperComponent” because they hide responsibilities and invite mixing concerns.

Only introduce a container component when there’s a real need: a chunk of UI that must own state or effects to stay coherent. Even then, keep it narrow. A good container owns one purpose (like “filter state”) and hands everything else off as props.

Messy components usually mix three kinds of data: real UI state (what the user changed), derived data (what you can compute), and server state (what comes from the network). If you treat all of it as local state, refactors get risky because you can accidentally change when things update.

Start by labeling each piece of data. Ask: does the user edit it, or can I compute it from props, state, and fetched data? Also ask: is this value owned here, or is it just passed through?

Derived values shouldn’t live in useState. Move them into a small function, or a memoized selector when it’s expensive. This reduces state updates and makes behavior easier to predict.

A safe pattern:

useState.useMemo.Effects break behavior when they do too much or react to the wrong dependencies. Aim for one effect per purpose: one for syncing to localStorage, one for fetching, one for subscriptions. If an effect reads many values, it’s usually hiding extra responsibilities.

If you’re using Claude Code, ask for a tiny change: split one effect into two, or move one responsibility into a helper. Then run characterization tests after each move.

Be careful with prop drilling. Replacing it with context helps only when it removes repeated wiring and clarifies ownership. A good sign is when context reads like an app-level concept (current user, theme, feature flags), not a workaround for one component tree.

Example: a table component might store both rows and filteredRows in state. Keep rows as state, compute filteredRows from rows plus query, and keep the filtering code in a pure function so it’s easy to test and hard to break.

Refactors go wrong most often when you change too much before you notice. The fix is simple: work in tiny checkpoints, and treat each checkpoint like a mini release. Even if you’re working in one branch, keep your changes PR-sized so you can see what broke and why.

After every meaningful move (extracting a component, changing how state flows), stop and prove you didn’t change behavior. That proof can be automated (tests) and manual (a quick set of checks in the browser). The goal isn’t perfection. It’s fast detection.

A practical checkpoint loop:

If you’re using a platform like Koder.ai, snapshots and rollback can act like safety rails while you iterate. You still want normal commits, but snapshots help when you need to compare a “known good” version against your current one, or when an experiment goes sideways.

Keep a simple behavior ledger as you go. It’s just a short note of what you verified, and it prevents you from re-checking the same things repeatedly.

For example:

When something breaks, the ledger tells you what to re-check, and your checkpoints make it cheap to revert.

Most refactors fail in small, boring ways. The UI still works, but a spacing rule disappears, a click handler fires twice, or a list starts losing focus while typing. Assistants can make this worse because the code looks cleaner even as behavior drifts.

One common cause is changing structure. You extract a component and wrap things in an extra <div>, or swap a <button> for a clickable <div>. CSS selectors, layout, keyboard navigation, and test queries can change without anyone noticing.

The traps that break behavior most often:

{} or () => {}) can trigger extra re-renders and reset child state. Keep an eye on props that used to be stable.useEffect, useMemo, or useCallback can introduce stale values or loops if dependencies change. If an effect used to run “on click,” don’t turn it into something that runs “whenever anything changes.”A concrete example: splitting a table component and changing row keys from an ID to an array index might look fine, but it can break selection state when rows reorder. Treat “clean” as a bonus. Treat “same behavior” as the requirement.

Before you merge, you want proof that the refactor kept behavior the same. The easiest signal is boring: everything still works without you having to “fix” the tests.

Run this quick pass after the last small change:

onChange still fires on user input, not on mount).A fast sanity check: open the component and do one weird flow, like triggering an error, retrying, then clearing filters. Refactors often break transitions even when the main path works.

If any item fails, revert the last change and redo it in a smaller step. That’s usually faster than debugging a big diff.

Picture a ProductTable component that does everything: fetches data, manages filters, controls pagination, opens a confirm dialog for delete, and handles row actions like edit, duplicate, and archive. It started small, then grew into a 900-line file.

The symptoms are familiar: state is scattered across useState calls, a couple of useEffects fire in a specific order, and one “harmless” change breaks pagination only when a filter is active. People stop touching it because it feels unpredictable.

Before changing structure, lock the behavior with a few React characterization tests. Focus on what users do, not internal state:

Now you can refactor in small commits. A clean extraction plan might look like this: FilterBar renders controls and emits filter changes; TableView renders rows and pagination; RowActions owns the action menu and confirm dialog UI; and a useProductTable hook owns the messy logic (query params, derived state, and side effects).

Order matters. Extract dumb UI first (TableView, FilterBar) by passing props through unchanged. Save the risky part for last: moving state and effects into useProductTable. When you do, keep the old prop names and event shapes so tests keep passing. If a test fails, you’ve found a behavior change, not a style issue.

If you want refactoring React components with Claude Code to feel safe every time, turn what you just did into a small template you can reuse. The goal isn’t more process. It’s fewer surprises.

Write a short playbook you can follow on any component, even when you’re tired or rushed:

Store this as a snippet in your notes or repo so the next refactor starts with the same safety rails.

Once the component is stable and easier to read, pick the next pass based on user impact. A common order is: accessibility first (labels, focus, keyboard), then performance (memoization, expensive renders), then cleanup (types, naming, dead code). Don’t mix all three in one pull request.

If you use a vibe-coding workflow like Koder.ai (koder.ai), planning mode can help you outline steps before you touch code, and snapshots and rollback can serve as checkpoints while you iterate. When you’re done, exporting the source code makes it easier to review the final diff and keep a clean history.

Stop refactoring when the tests cover the behavior you’re afraid to break, the next change would be a new feature, or you feel the urge to “make it perfect.” If splitting a large form removed tangled state and your tests cover validation and submit, ship it. Save the remaining ideas as a short backlog for later.

React refactors often change identity and timing without you noticing. Common behavior breaks include:

key changed.Assume a structural change can be a behavior change until tests prove otherwise.

Use a tight, checkable goal focused on structure, not “improvements.” A good goal reads like:

Avoid goals like “make it better” unless you have a specific metric and a known bottleneck.

Treat the component as a black box and write down what users can observe:

If your notes feel boring and specific, they’re useful.

Add characterization tests that describe what the component does today, even if it’s weird.

Practical targets:

Assert outcomes in the UI, not internal hook calls.

Ask it to act like a careful pair programmer:

Don’t accept a big “rewrite-style” diff; push for incremental changes you can verify.

Start by extracting pure presentational pieces:

Copy-and-wire first; cleanup later. Once the UI is split safely, then tackle state/effects in smaller moves.

Use stable keys tied to real identity (like an ID), not array indexes.

Index keys often “work” until you sort, filter, insert, or remove rows—then React reuses the wrong instances and you see bugs like:

If your refactor changes keys, treat it as high risk and test the reorder cases.

Keep derived values out of useState when you can compute them from existing inputs.

A safe approach:

filteredRows) from + Use checkpoints so every step is easy to revert:

If you’re working in Koder.ai, snapshots and rollback can complement normal commits when an experiment goes sideways.

Stop when behavior is locked and the code is clearly easier to change. Good stop signals:

Ship the refactor, then log follow-ups (accessibility, performance, cleanup) as separate work.

rowsqueryuseMemo only when computation is expensiveThis reduces update weirdness and makes the component easier to reason about.