Oct 16, 2025·8 min

REST vs gRPC: Choosing the Right API Style for Your App

Compare REST and gRPC for real projects: performance, tooling, streaming, compatibility, and team fit. Use a simple checklist to choose confidently.

Compare REST and gRPC for real projects: performance, tooling, streaming, compatibility, and team fit. Use a simple checklist to choose confidently.

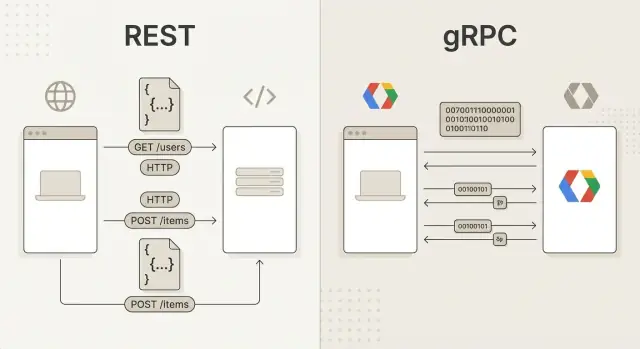

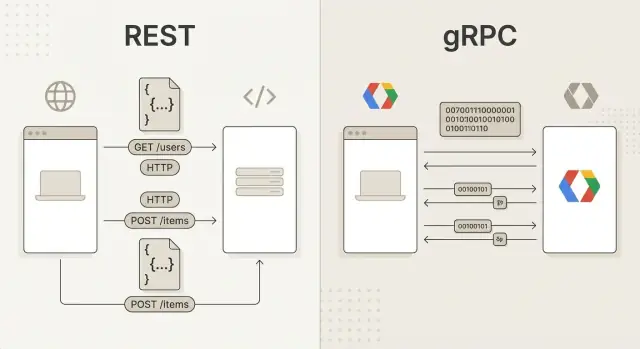

When people compare REST and gRPC, they’re really comparing two different ways for software to “talk” over a network.

REST is a style of API design built around resources—things your app manages, like users, orders, or invoices. You interact with those resources using familiar HTTP requests:

GET /users/123)POST /orders)Responses are commonly JSON, which is easy to inspect and widely supported. REST tends to feel intuitive because it maps closely to how the web works—and because you can test it with a browser or simple tools.

gRPC is a framework for remote procedure calls (RPC). Instead of thinking in “resources,” you think in methods you want to run on another service, like CreateOrder or GetUser.

Under the hood, gRPC typically uses:

.proto file) that can generate client and server codeThe result often feels like calling a local function—except it’s running somewhere else.

This guide helps you choose based on real constraints: performance expectations, client types (browser vs mobile vs internal services), real-time needs, team workflow, and long-term maintenance.

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Many teams use REST for public or third-party APIs and gRPC for internal service-to-service communication—but your constraints and goals should drive the choice.

Before comparing features, get clear on what you’re optimizing for. REST and gRPC can both work well, but they shine under different constraints.

Start with clients.

On the public internet, you’ll care about proxies, caching layers, and compatibility with diverse tooling. REST over HTTP is widely supported and tends to navigate enterprise networks more predictably.

Inside a private network (or between services in the same platform), you can take advantage of gRPC’s tighter protocol and more structured communication—especially when you control both ends.

Ask what “normal traffic” looks like:

If you need streaming (events, progress updates, continuous feeds), factor that in early. You can build real-time patterns with REST-adjacent approaches, but gRPC’s streaming model is often a more natural fit when both sides can support it.

Pick what your team can ship and operate confidently. Consider existing API standards, debugging habits, release cadence, and how quickly new developers can become productive. A “best” protocol that slows delivery or increases operational risk isn’t actually best for your project.

At the protocol level, REST and gRPC both boil down to “a client calls a server,” but they describe that call differently: REST centers on HTTP resources and status codes, while gRPC centers on remote methods and a strict schema.

REST APIs typically run over HTTP/1.1, and increasingly HTTP/2 as well. The “shape” of a REST call is defined by:

/users/123)GET, POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE200, 201, 400, 401, 404, 500, etc.Accept, Content-Type)The typical pattern is request/response: the client sends an HTTP request, and the server returns a response with a status code, headers, and a body (often JSON).

gRPC always uses HTTP/2, but it doesn’t expose “resources + verbs” as the primary interface. Instead, you define services with methods (like CreateUser or GetUser) and call them as remote procedure calls.

Alongside the message payload, gRPC supports:

REST asks: “What resource are you operating on, and which HTTP verb fits?”

gRPC asks: “Which method are you calling, and what typed message does it accept/return?”

That difference affects naming, error handling (HTTP status codes vs gRPC status), and how clients are generated.

.proto schema is the contract. It defines services, methods, and strongly typed messages, enabling reliable code generation and clearer compatibility rules as the API evolves.Performance is one of the most cited reasons teams consider gRPC—but the win is not automatic. The real question is what kind of “performance” you need: lower latency per call, higher throughput under load, lower bandwidth cost, or better server efficiency.

Most REST APIs use JSON over HTTP/1.1. JSON is easy to inspect, log, and debug, which is a practical kind of efficiency for teams.

The trade-off is that JSON is verbose and needs more CPU to parse and generate, especially when payloads get large or calls get frequent. HTTP/1.1 can also add connection and request overhead when clients make many parallel requests.

REST can also be a performance win in read-heavy architectures: HTTP caching (via headers like ETag and Cache-Control) can reduce repeated requests dramatically—particularly when combined with CDNs.

gRPC typically uses Protocol Buffers (binary) over HTTP/2. That usually means:

Those benefits show up most clearly in service-to-service calls with high request volume, or when you’re pushing a lot of data around inside a microservices system.

On a quiet system, REST and gRPC can look similarly fast. The differences become more obvious when concurrency increases.

Performance differences matter most when you have high-frequency internal calls, large payloads, tight mobile bandwidth constraints, or strict SLOs.

They matter less when your API is dominated by database time, third-party calls, or human-scale usage (admin dashboards, typical CRUD apps). In those cases, clarity, cacheability, and client compatibility may outweigh raw protocol efficiency.

Real-time features—live dashboards, chat, collaboration, telemetry, notifications—depend on how your API handles “ongoing” communication, not just one-off requests.

REST is fundamentally request/response: the client asks, the server answers, and the connection ends. You can build near-real-time behavior, but it usually relies on patterns around REST rather than within it:

(For browser-based real-time, teams often add WebSockets or SSE alongside REST; that’s a separate channel with its own operational model.)

gRPC supports multiple call types over HTTP/2, and streaming is built into the model:

This makes gRPC a strong fit when you want sustained, low-latency message flow without constantly creating new HTTP requests.

Streaming shines for:

Long-lived streams change how you operate systems:

If “real-time” is core to your product, gRPC’s streaming model can reduce complexity compared to layering polling/webhooks (and possibly WebSockets) on top of REST.

Choosing between REST and gRPC isn’t just about speed—your team will live with the API every day. Tooling, onboarding, and how safely you can evolve an interface often matter more than raw throughput.

REST feels familiar because it rides on plain HTTP and usually speaks JSON. That means the toolbox is universal: browser devtools, curl, Postman/Insomnia, proxies, and logs you can read without special viewers.

When something breaks, debugging is often straightforward: replay a request from a terminal, inspect headers, and compare responses side-by-side. This convenience is a big reason REST is common for public APIs and for teams that expect a lot of ad-hoc testing.

gRPC typically uses Protocol Buffers and code generation. Instead of manually assembling requests, developers call typed methods in their language of choice.

The payoff is type safety and a clearer contract: fields, enums, and message shapes are explicit. This can reduce “stringly-typed” bugs and mismatches between client and server—especially in service-to-service calls and microservices communication.

REST is easier to pick up quickly: “send an HTTP request to this URL.” gRPC asks new team members to understand .proto files, code generation, and sometimes different debugging workflows. Teams comfortable with strong typing and shared schemas tend to adapt faster.

With REST/JSON, change management often relies on conventions (adding fields, deprecating endpoints, versioned URLs). With gRPC/Protobuf, compatibility rules are more formal: adding fields is usually safe, but renaming/removing fields or changing types can break consumers.

In both styles, maintainability improves when you treat the API as a product: document it, automate contract tests, and publish a clear deprecation policy.

Choosing between REST and gRPC often comes down to who will call your API—and from what environments.

REST over HTTP with JSON is widely supported: browsers, mobile apps, command-line tools, low-code platforms, and partner systems. If you’re building a public API or expect third-party integrations, REST usually minimizes friction because consumers can start with simple requests and gradually adopt better tooling.

REST also fits naturally with web constraints: browsers handle HTTP well, caches and proxies understand it, and debugging is straightforward with common tools.

gRPC shines when you control both ends of the connection (your services, your internal apps, your backend teams). It uses HTTP/2 and Protocol Buffers, which can be a big win for performance and consistency—but not every environment can adopt it easily.

Browsers, for example, don’t support “full” native gRPC calls directly. You can use gRPC-Web, but that adds components and constraints (proxies, specific content types, and different tooling). For third parties, requiring gRPC can be a higher barrier than providing a REST endpoint.

A common pattern is to keep gRPC internally for service-to-service calls and expose REST externally via a gateway or translation layer. That lets partners use familiar HTTP/JSON while your internal systems keep a strongly typed contract.

If your audience includes unknown third parties, REST is usually the safer default. If your audience is mostly your own services, gRPC is often the better fit.

Security and operability are often where “nice in a demo” becomes “hard in production.” REST and gRPC can both be secure and observable, but they fit different infrastructure patterns.

REST typically rides over HTTPS (TLS). Authentication is usually carried in standard HTTP headers:

Because REST leans on familiar HTTP semantics, it’s easy to integrate with existing WAFs, reverse proxies, and API gateways that already understand headers, paths, and methods.

gRPC also uses TLS, but authentication is commonly passed via metadata (key/value pairs similar to headers). It’s normal to add:

authorization: Bearer …)For REST, most platforms have out-of-the-box access logs, status codes, and request timing. You can get far with structured logs plus standard metrics like latency percentiles, error rates, and throughput.

For gRPC, observability is excellent once instrumented, but it’s less “automatic” in some stacks because you’re not dealing with plain URLs. Prioritize:

Common REST setups place an ingress or API gateway at the edge, handling TLS termination, auth, rate limiting, and routing.

gRPC works well behind an ingress too, but you’ll often need components that fully support HTTP/2 and gRPC features. In microservices environments, a service mesh can simplify mTLS, retries, timeouts, and telemetry for gRPC—especially when many internal services talk to each other.

Operational takeaway: REST usually integrates more smoothly with “standard web” tooling, while gRPC shines when you’re ready to standardize on deadlines, service identity, and uniform telemetry across internal calls.

Most teams don’t pick REST or gRPC in the abstract—they pick what fits the shape of their users, clients, and traffic. These scenarios tend to make the trade-offs clearer.

REST is often the “safe” choice when your API needs to be broadly consumable and easy to explore.

Use REST when you’re building:

REST tends to shine at the edges of your system: it’s readable, cache-friendly in many cases, and plays nicely with gateways, documentation, and common infrastructure.

gRPC is usually the better fit for service-to-service communication where efficiency and strong contracts matter.

Pick gRPC when you have:

In these cases, gRPC’s binary encoding and HTTP/2 features (like multiplexing) often reduce overhead and make performance more predictable as internal traffic grows.

A common, practical architecture is:

This pattern limits gRPC’s compatibility constraints to your own controlled environment, while still giving internal systems the benefits of typed contracts and efficient service-to-service calls.

A few choices regularly cause pain later:

/doThing and losing the clarity of resource-oriented design.If you’re unsure, default to REST for external APIs and adopt gRPC where you can prove it helps: inside your platform, on hot paths, or where streaming and tight contracts are genuinely valuable.

Choosing between REST and gRPC is easier when you start with who will use the API and what they need to accomplish—not what’s trendy.

Ask:

Use this as a decision filter:

Pick a representative endpoint (not “Hello World”) and build it as:

Measure:

If you want to move quickly on this kind of pilot, a vibe-coding workflow can help: for example, on Koder.ai you can scaffold a small app and backend from a chat prompt, then try both a REST surface and a gRPC service internally. Because Koder.ai generates real projects (React for web, Go backends with PostgreSQL, Flutter for mobile), it’s a practical way to validate not just protocol benchmarks, but also the developer experience—documentation, client integration, and deployment. Features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback are also useful when you’re iterating on API shape.

Document the decision, the assumptions (clients, traffic, streaming), and the metrics you used. Re-check when requirements change (new external consumers, higher throughput, real-time features).

Often, yes—especially for service-to-service calls—but not automatically.

gRPC tends to be efficient because it uses HTTP/2 (multiplexing many calls over one connection) and a compact binary format (Protocol Buffers). That can reduce CPU time and bandwidth compared with JSON-over-HTTP.

Real-world speed depends on:

If performance is a key goal, benchmark your specific endpoints with realistic data.

Browsers can’t use “full” gRPC directly because they don’t expose the low-level HTTP/2 features gRPC expects.

Your options are:

If you have third-party or browser-heavy clients, REST is usually the simplest default.

gRPC is designed around Protobuf contracts, code generation, and strict typing. You can send other formats, but you’ll lose many benefits.

Protobuf helps when you want clear contracts, smaller payloads, and consistent client/server code.

For REST, common approaches are /v1/ in the path or versioning via headers; keep changes backward-compatible when possible.

For gRPC, prefer evolving messages safely: add new fields, avoid renaming, and don’t reuse removed field numbers. When changes are truly breaking, publish a new service or package name (effectively a new major version).

REST is usually the default for public APIs because almost any client can call it with plain HTTP and JSON.

Pick REST if you expect:

curl/PostmangRPC is often a better fit when you control both sides of the connection and want a strongly typed contract.

It’s a strong choice for:

Not always. gRPC commonly wins on payload size and connection efficiency (HTTP/2 multiplexing + Protobuf), but end-to-end results depend on your bottlenecks.

Benchmark with realistic data because performance can be dominated by:

REST naturally supports HTTP caching with headers like Cache-Control and ETag, plus CDNs and shared proxies.

gRPC is typically not cache-friendly in the same way because calls are method-oriented and often treated as non-cacheable by standard HTTP infrastructure.

If caching is a key requirement, REST is usually the simpler path.

Browsers can’t use “native” gRPC directly due to how gRPC relies on HTTP/2 features that browser APIs don’t expose.

Common options:

gRPC is designed around a .proto schema that defines services, methods, and message types. That schema enables code generation and clear compatibility rules.

You can technically use other encodings, but you give up many benefits (type safety, compact messages, standardized tooling).

If you want gRPC’s main advantages, treat Protobuf as part of the package.

REST typically communicates outcomes via HTTP status codes (e.g., 200, 404, 500) and response bodies.

gRPC returns a gRPC status code (like OK, NOT_FOUND, UNAVAILABLE) plus optional error details.

Practical tip: standardize error mapping early (including retryable vs non-retryable errors) so clients behave consistently across services.

Streaming is a first-class feature in gRPC, with built-in support for:

REST is primarily request/response; “real-time” usually requires additional patterns like polling, long polling, webhooks, WebSockets, or SSE.

For REST, common practices include:

/v1/... paths or headersFor gRPC/Protobuf:

Yes, and it’s a common architecture:

A gateway or backend-for-frontend layer can translate REST/JSON to gRPC/Protobuf. This reduces client friction while still getting gRPC’s contract and performance benefits inside your platform.