Aug 08, 2025·8 min

Roy Fielding’s REST: Constraints Shaping Modern Web APIs

Understand Roy Fielding’s REST constraints and how they shape practical API and web app design: client-server, stateless, cache, uniform interface, layers, and more.

Why Roy Fielding’s REST Still Matters

Roy Fielding isn’t just a name attached to an API buzzword. He was one of the key authors of the HTTP and URI specifications and, in his PhD dissertation, described an architectural style called REST (Representational State Transfer) to explain why the Web works as well as it does.

That origin matters because REST wasn’t invented to make “nice-looking endpoints.” It was a way to describe the constraints that let a global, messy network still scale: many clients, many servers, intermediaries, caching, partial failures, and continuous change.

What you’ll get from this post

If you’ve ever wondered why two “REST APIs” feel completely different—or why a small design choice later turns into pagination pain, caching confusion, or breaking changes—this guide is meant to reduce those surprises.

You’ll come away with:

- clearer decision-making when designing or evaluating an API

- a better vocabulary for discussing trade-offs with your team

- a practical sense of which REST ideas matter most in real projects

REST in One Page: Style, Not a Standard

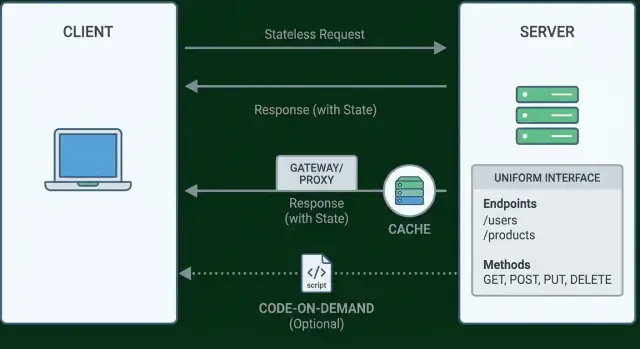

REST isn’t a checklist, a protocol, or a certification. Fielding described it as an architectural style: a set of constraints that, when applied together, produce systems that scale like the Web—simple to use, able to evolve over time, and friendly to intermediaries (proxies, caches, gateways) without constant coordination.

The problem REST was solving

The early Web needed to work across many organizations, servers, networks, and client types. It had to grow without central control, survive partial failures, and allow new features to appear without breaking old ones. REST addresses that by favoring a small number of widely shared concepts (like identifiers, representations, and standard operations) over custom, tightly coupled contracts.

“Architectural constraints” in plain terms

A constraint is a rule that limits design freedom in exchange for benefits. For example, you might give up server-side session state so requests can be handled by any server node, which improves reliability and scaling. Each REST constraint makes a similar trade: less ad-hoc flexibility, more predictability and evolvability.

REST vs. “REST-like” APIs

Many HTTP APIs borrow REST ideas (JSON over HTTP, URL endpoints, maybe status codes) but don’t apply the full set of constraints. That’s not “wrong”—it often reflects product deadlines or internal-only needs. It’s simply useful to name the difference: an API can be resource-oriented without being fully REST.

A one-paragraph mental model

Think of a REST system as resources (things you can name with URLs) that clients interact with through representations (the current view of a resource, like JSON or HTML), guided by links (next actions and related resources). The client doesn’t need secret out-of-band rules; it follows standard semantics and navigates using links, the same way a browser moves through the Web.

Resources and Representations: The Core Vocabulary

Before getting lost in constraints and HTTP details, REST starts with a simple vocabulary shift: think in resources, not actions.

Resource = a noun you can identify

A resource is an addressable “thing” in your system: a user, an invoice, a product category, a shopping cart. The important part is that it’s a noun with an identity.

That’s why /users/123 reads naturally: it identifies the user with ID 123. Compare that to action-shaped URLs like /getUser or /updateUserPassword. Those describe verbs—operations—not the thing you’re operating on.

REST doesn’t say you can’t perform actions. It says actions should be expressed through the uniform interface (for HTTP APIs, that usually means methods like GET/POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE) acting on resource identifiers.

Representation = a view of the resource

A representation is what you send over the wire as a snapshot or view of that resource at a point in time. The same resource can have multiple representations.

For example, the resource /users/123 could be represented as JSON for an app, or HTML for a browser.

GET /users/123

Accept: application/json

Might return:

{

"id": 123,

"name": "Asha",

"email": "[email protected]"

}

While:

GET /users/123

Accept: text/html

Might return an HTML page rendering the same user details.

The key idea: the resource is not the JSON and it’s not the HTML. Those are just formats used to represent it.

Why this framing changes API design

Once you model your API around resources and representations, several practical decisions get easier:

- Naming stays stable.

/users/123remains valid even if your UI, workflows, or data model evolves. - Endpoints get simpler. Instead of inventing a new URL for every operation, you reuse resource URLs and vary the method or representation.

- Client code becomes less coupled. Clients focus on “fetch the user” or “update fields on the user” rather than memorizing a catalog of action endpoints.

This resource-first mindset is the foundation that the REST constraints build on. Without it, “REST” often collapses into “JSON over HTTP with some nice URL patterns.”

Constraint 1: Client–Server Separation

Client–server separation is REST’s way of enforcing a clean division of responsibilities. The client focuses on the user experience (what people see and do), while the server focuses on data, rules, and persistence (what’s true and what’s allowed). When you keep those concerns apart, each side can change without forcing a rewrite of the other.

What lives on the client vs. the server?

In everyday terms, the client is the “presentation layer”: screens, navigation, form validation for quick feedback, and optimistic UI behavior (like showing a new comment immediately). The server is the “source of truth”: authentication, authorization, business rules, data storage, auditing, and anything that must remain consistent across devices.

A practical rule: if a decision affects security, money, permissions, or shared data consistency, it belongs on the server. If a decision affects only how the experience feels (layout, local input hints, loading states), it belongs on the client.

Why it fits modern app patterns

This constraint maps directly to common setups:

- SPA + API: a web app (React/Vue/etc.) iterates on UI while the API continues serving resources.

- Mobile apps: iOS and Android clients can share the same server rules and endpoints.

- Third-party integrations: partners consume the same server capabilities without needing your UI.

Client–server separation is what makes “one backend, many frontends” realistic.

Common pitfall: leaking UI state into server sessions

A frequent mistake is storing UI workflow state on the server (for example: “which step of checkout the user is on”) in a server-side session. That couples the backend to a particular screen flow and makes scaling harder.

Prefer sending the necessary context with each request (or deriving it from stored resources), so the server stays focused on resources and rules—not on remembering how a specific UI is progressing.

Constraint 2: Stateless Interactions

Statelessness means the server does not need to remember anything about a client between requests. Each request carries all the information required to understand it and respond correctly—who the caller is, what they want, and any context needed to process it.

Why this matters

When requests are independent, you can add or remove servers behind a load balancer without worrying about “which server knows my session.” That improves scalability and resilience: any instance can handle any request.

It also simplifies operations. Debugging is often easier because the full context is visible in the request (and logs), rather than hidden in server-side session memory.

The trade-offs you feel in real APIs

Stateless APIs typically send a bit more data per call. Instead of relying on a stored server session, clients include credentials and context each time.

You also have to be explicit about “stateful” user flows (like pagination or multi-step checkouts). REST doesn’t forbid multi-step experiences—it just pushes the state to the client or to server-side resources that are identified and retrievable.

Practical patterns (and what they solve)

- Auth tokens (e.g., Bearer JWTs): Every request includes an

Authorization: Bearer …header so any server can authenticate it. - Idempotency keys: For operations like “create payment,” clients send an

Idempotency-Keyso retries don’t accidentally duplicate work. - Correlation IDs: A header like

X-Correlation-Idlets you trace one user action across services and logs, even in a distributed system.

For pagination, avoid “server remembers page 3.” Prefer explicit parameters like ?cursor=abc or a next link that the client can follow, keeping navigation state in the responses rather than in server memory.

Constraint 3: Cacheable Responses

Design resources first

Describe your API resources in chat and let Koder.ai scaffold the endpoints.

Caching is about reusing a previous response safely so the client (or something in between) doesn’t have to ask your server to do the same work again. Done well, it cuts latency for users and reduces load for you—without changing the meaning of the API.

What “cacheable” means in practice

A response is cacheable when it’s safe for another request to receive the same payload for some period of time. In HTTP, you communicate that intent with caching headers:

Cache-Control: the main switchboard (how long to keep it, whether it can be stored by shared caches, etc.)ETagandLast-Modified: validators that let clients ask “has this changed?” and get a cheap “not modified” answerExpires: an older way to express freshness, still seen in the wild

This is bigger than “browser caching.” Proxies, CDNs, API gateways, and even mobile apps can reuse responses when the rules are clear.

What’s usually safe to cache (and what isn’t)

Good candidates:

- Public, identical-for-everyone data (product catalogs, documentation, feature flags that aren’t user-specific)

- Read-only resources that change infrequently (static configuration, reference data)

- GET responses that don’t depend on cookies or authorization

Usually poor candidates:

- Personal data tied to an account (profiles, orders, messages)

- Auth-related responses (token exchanges, session state)

- Anything that varies per user unless you explicitly handle it (e.g., with

privatecaching rules)

Practical outcomes you’ll notice

- Faster pages and snappier apps (less waiting on the network)

- Lower server and database costs (fewer repeated computations)

- Fewer “rate limit” incidents (cached reads reduce request volume)

The key idea: caching isn’t an afterthought. It’s a REST constraint that rewards APIs that communicate freshness and validation clearly.

Constraint 4: The Uniform Interface (What It Really Means)

The uniform interface is often mistaken for “use GET to read and POST to create.” That’s only a small slice. Fielding’s idea is bigger: APIs should feel consistent enough that clients don’t need special, endpoint-by-endpoint knowledge to use them.

The four parts of the uniform interface

-

Identification of resources: You name things (resources) with stable identifiers (typically URLs), not actions. Think

/orders/123, not/createOrder. -

Manipulation via representations: Clients change a resource by sending a representation (JSON, HTML, etc.). The server controls the resource; the client exchanges representations of it.

-

Self-descriptive messages: Each request/response should carry enough information to understand how to process it—method, status code, headers, media type, and a clear body. If meaning is hidden in out-of-band docs, clients become tightly coupled.

-

Hypermedia (HATEOAS): Responses should include links and allowed actions so clients can follow the workflow without hard-coding every URL pattern.

Why it reduces coupling

A consistent interface makes clients less dependent on internal server details. Over time, that means fewer breaking changes, fewer “special cases,” and less rework when teams evolve endpoints.

Practical heuristics you can apply

- Use status codes consistently: e.g.,

200for successful reads,201for created resources (withLocation),400for validation issues,401/403for auth,404when a resource doesn’t exist. - Standardize your error format across the API. Example fields:

code,message,details,requestId. - Keep media types and headers meaningful (

Content-Type, caching headers), so messages explain themselves.

Uniform interface is about predictability and evolvability, not just “correct verbs.”

Self-Descriptive Messages: Designing for Comprehension

Flutter app for your API

Create a Flutter app that consumes your API and handles paging and retries.

A “self-descriptive” message is one that tells the receiver how to interpret it—without requiring out-of-band tribal knowledge. If a client (or intermediary) can’t understand what a response means just by looking at the HTTP headers and body, you’ve created a private protocol riding on HTTP.

Use media types to explain the payload

The simplest win is being explicit with Content-Type (what you’re sending) and often Accept (what you want back). A response with Content-Type: application/json tells a client the basic parsing rules, but you can go further with vendor or profile-based media types when meaning matters.

Examples of approaches:

- Generic media type + stable fields:

application/jsonwith a carefully maintained schema. Easiest for most teams. - Vendor media types:

application/vnd.acme.invoice+jsonto signal a specific representation. - Profiles: keep

application/json, add aprofileparameter or link to a profile that defines semantics.

Versioning and compatibility (without breaking clients)

Versioning should protect existing clients. Popular options include:

- URL versioning (

/v1/orders): obvious, but can encourage “forking” representations instead of evolving them. - Header or media type versioning (via

Accept): keeps URLs stable and makes “what this means” part of the message. - Additive evolution: prefer adding new fields and keeping old ones working; deprecate gradually.

Whatever you choose, aim for backward compatibility by default: don’t rename fields casually, don’t change meaning silently, and treat removals as breaking changes.

Consistent errors and clear naming

Clients learn faster when errors look the same everywhere. Pick one error shape (e.g., code, message, details, traceId) and use it across endpoints. Use clear, predictable field names (createdAt vs. created_at) and stick to one convention.

Documentation helps—but clarity must live in the message

Good docs accelerate adoption, but they can’t be the only place where meaning exists. If a client must read a wiki to know whether status: 2 means “paid” or “pending,” the message isn’t self-descriptive. Well-designed headers, media types, and readable payloads reduce that dependence and make systems easier to evolve.

Hypermedia (HATEOAS): The Most Skipped REST Idea

Hypermedia (often summarized as HATEOAS: Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State) means a client doesn’t have to “know” the API’s next URLs in advance. Instead, each response includes discoverable next steps as links: where to go next, what actions are possible, and sometimes which HTTP method to use.

What it looks like in practice

Rather than hard-coding paths like /orders/{id}/cancel, the client follows links provided by the server. The server is effectively saying: “Given the current state of this resource, here are the valid moves.”

{

"id": "ord_123",

"status": "pending",

"total": 49.90,

"_links": {

"self": { "href": "/orders/ord_123" },

"payment":{ "href": "/orders/ord_123/payment", "method": "POST" },

"cancel": { "href": "/orders/ord_123", "method": "DELETE" }

}

}

If the order later becomes paid, the server might stop including cancel and add refund—without breaking a well-behaved client.

When hypermedia helps most

Hypermedia shines when flows evolve: onboarding steps, checkout, approvals, subscriptions, or any process where “what’s allowed next” changes based on state, permissions, or business rules.

It also reduces hard-coded URLs and brittle client assumptions. You can reorganize routes, introduce new actions, or deprecate old ones while keeping clients functional as long as you maintain the meaning of link relations.

Why teams skip it (and what they lose)

Teams often skip HATEOAS because it can feel like extra work: defining link formats, agreeing on relation names, and teaching client developers to follow links instead of constructing URLs.

What you lose is a key REST benefit: loose coupling. Without hypermedia, many APIs become “RPC over HTTP”—they may use HTTP, but clients still depend heavily on out-of-band documentation and fixed URL templates.

Constraint 5: Layered System

A layered system means a client doesn’t have to know (and often can’t tell) whether it’s talking to the “real” origin server or to intermediaries along the way. Those layers can include API gateways, reverse proxies, CDNs, auth services, WAFs, service meshes, and even internal routing between microservices.

Why layers are useful

Layers create clean boundaries. Security teams can enforce TLS, rate limits, authentication, and request validation at the edge without changing every backend service. Operations teams can scale horizontally behind a gateway, add caching in a CDN, or shift traffic during incidents. For clients, it can simplify things: one stable API endpoint, consistent headers, and predictable error formats.

The trade-offs you feel in practice

Intermediaries can introduce hidden latency (extra hops, extra handshakes) and make debugging harder: the bug might live in the gateway rules, the CDN cache, or the origin code. Caching can also get confusing when different layers cache differently, or when a gateway rewrites headers that affect cache keys.

Practical tips that keep layers from hurting you

- Use tracing IDs end-to-end: accept a request ID (or generate one) and propagate it through every hop; include it in responses and logs.

- Make error propagation explicit: standardize error bodies and map upstream failures clearly (don’t turn every issue into a generic 500).

- Set timeouts per hop: gateway timeouts, upstream timeouts, and client timeouts should be aligned to avoid “mystery” disconnects.

- Document caching behavior: be clear about which responses are cacheable and which headers intermediaries must preserve.

Layers are powerful—when the system stays observable and predictable.

Constraint 6 (Optional): Code-on-Demand

Caching done right

Add Cache-Control and ETag handling to GET responses without manual boilerplate.

Code-on-demand is the one REST constraint that’s explicitly optional. It means a server can extend a client by sending executable code that runs on the client side. Instead of shipping every behavior in the client ahead of time, the client can download new logic as needed.

The web’s familiar example: JavaScript

If you’ve ever loaded a webpage that then becomes interactive—validating a form, rendering a chart, filtering a table—you’ve already used code-on-demand. The server delivers HTML and data, plus JavaScript that runs in the browser to provide behavior.

This is a big reason the web can evolve quickly: a browser can remain a general-purpose client, while sites deliver new functionality without requiring the user to install a whole new application.

Why it’s optional (and why many APIs skip it)

REST still “works” without code-on-demand because the other constraints already enable scalability, simplicity, and interoperability. An API can be purely resource-oriented—serving representations like JSON—while clients implement their own behavior.

In fact, many modern Web APIs intentionally avoid sending executable code because it complicates:

- Security: executable code is a larger attack surface (injection, supply-chain issues, malicious scripts).

- Content policies: browsers enforce restrictions like Content Security Policy (CSP), and organizations may block inline scripts or unknown origins.

- Auditing and compliance: it’s harder to prove what code ran on a client at a given time, especially if it’s fetched dynamically.

When code-on-demand can still make sense

Code-on-demand can be useful when you control the client environment and need to roll out UI behavior quickly, or when you want a thin client that downloads “plugins” or rules from a server. But it’s best treated as an extra tool, not a requirement.

The key takeaway: you can fully follow REST without code-on-demand—and many production APIs do—because the constraint is about optional extensibility, not the foundation of resource-based interaction.

Applying REST Today: Practical Choices and Common Missteps

Most teams don’t reject REST—they adopt a “REST-ish” style that keeps HTTP as a transport while quietly dropping key constraints. That can be fine, as long as it’s a conscious trade-off and not an accident that shows up later as brittle clients and costly rewrites.

Common REST-ish shortcuts (and why they happen)

A few patterns show up again and again:

- RPC endpoints:

/doThing,/runReport,/users/activate—easy to name, easy to wire up. - Verb-heavy URLs:

/createOrder,/updateProfile,/deleteItem—HTTP methods become an afterthought. - Hidden sessions: “Stateless” APIs that still rely on sticky sessions, server memory, or implicit workflow state.

These choices often feel productive early on because they mirror internal function names and business operations.

Consequences you’ll notice later

- Brittle clients: If clients depend on specific endpoint shapes and ad-hoc behaviors, small server refactors become breaking changes.

- Hard versioning: When URLs encode actions rather than stable resources, you end up versioning behavior instead of evolving representations.

- Cache misses (and higher latency): Ignoring cache headers or using POST for everything prevents intermediaries (and browsers) from helping you.

- Scaling issues: Hidden server-side session state complicates horizontal scaling and makes failures harder to recover from.

A pragmatic alignment checklist

Use this as a “how REST are we, really?” review:

- Name resources, not actions: prefer

/orders/{id}over/createOrder. - Use HTTP methods intentionally: GET for retrieval, POST for creation, PUT/PATCH for updates, DELETE for removal.

- Make requests independent: no server memory required to understand “what step the client is on.”

- Leverage caching where safe: define

Cache-Control,ETag, andVaryfor GET responses. - Standardize errors and media types: consistent status codes and response shapes reduce special cases.

Where this shows up when you’re actually building

REST constraints aren’t just theory—they’re guardrails you feel while shipping. When you’re generating an API quickly (for example, scaffolding a React frontend with a Go + PostgreSQL backend), the easiest mistake is to let “whatever is fastest to wire up” dictate your interface.

If you’re using a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai to build a web app from chat, it helps to bring these REST constraints into the conversation early—naming resources first, staying stateless, defining consistent error shapes, and deciding where caching is safe. That way, even rapid iteration still produces APIs that are predictable for clients and easier to evolve. (And because Koder.ai supports source code export, you can keep refining the API contract and implementation as requirements mature.)

Takeaways for API and web app teams

Define your key resources first, then choose constraints consciously: if you’re skipping caching or hypermedia, document why and what you’re using instead. The goal isn’t purity—it’s clarity: stable resource identifiers, predictable semantics, and explicit trade-offs that keep clients resilient as your system evolves.

FAQ

What did Roy Fielding mean by “REST,” and why isn’t it a standard?

REST (Representational State Transfer) is an architectural style Roy Fielding described to explain why the Web scales.

It’s not a protocol or certification—it's a set of constraints (client–server, statelessness, cacheability, uniform interface, layered system, optional code-on-demand) that trade some flexibility for scalability, evolvability, and interoperability.

Why do two “REST APIs” often feel completely different?

Because many APIs adopt only some REST ideas (like JSON over HTTP and nice URLs) while skipping others (like cacheability rules or hypermedia).

Two “REST APIs” can feel very different depending on whether they:

- model stable resources vs. action endpoints

- use HTTP semantics consistently (methods, status codes, headers)

- support caching and intermediaries

- reduce client coupling with discoverable links

What’s the practical difference between “resources” and “actions” in URL design?

A resource is a noun you can identify (e.g., /users/123). An action endpoint is a verb baked into the URL (e.g., /getUser, /updatePassword).

Resource-oriented design tends to age better because identifiers stay stable while workflows and UI change. Actions can still exist, but they’re usually expressed via HTTP methods and representations rather than verb-shaped paths.

What is a “representation,” and why is the resource not the JSON?

A resource is the concept (“user 123”). A representation is the snapshot you transfer (JSON, HTML, etc.).

This matters because you can evolve or add representations without changing the resource identifier. Clients should depend on the resource meaning, not on one specific payload format.

How does client–server separation help real-world API teams?

Client–server separation keeps concerns independent:

- Client: UI, interaction, navigation, local validation, loading states

- Server: authentication/authorization, business rules, persistence, auditing

If a decision affects security, money, permissions, or shared consistency, it belongs on the server. This separation enables “one backend, many frontends” (web, mobile, partners).

What does “stateless” mean for an HTTP API, and what changes in practice?

Statelessness means the server doesn’t rely on stored client session state to understand a request. Each request includes what’s needed (auth + context).

Benefits include easier horizontal scaling (any node can handle any request) and simpler debugging (context is visible in logs).

Common patterns:

Authorization: Bearer …on every call

Which caching headers matter most, and when should I use them?

Cacheable responses let clients and intermediaries reuse responses safely, reducing latency and server load.

Practical HTTP tools:

Cache-Controlfor freshness and scope- / for validation ()

Is REST just “use GET/POST/PUT/DELETE correctly,” or is it more than that?

The uniform interface is about consistency so clients don’t need endpoint-by-endpoint special rules.

In practice, focus on:

What is HATEOAS (hypermedia), and when is it actually worth doing?

Hypermedia means responses include links to valid next actions, so clients follow links instead of hard-coding URL templates.

It helps most when flows change based on state or permissions (checkout, approvals, onboarding). A client can remain resilient if the server adds/removes allowed actions by changing the link set.

Teams often skip it because it adds design work (link formats, relation names), but the trade-off is tighter coupling to documentation and fixed routes.

How do “layered systems” affect API behavior, performance, and debugging?

A layered system allows intermediaries (CDNs, gateways, proxies, auth layers) so clients don’t need to know which component served the response.

To keep layers from becoming a debugging nightmare:

- propagate a request/correlation ID through every hop

- keep error mapping explicit (don’t turn everything into a generic

500) - align timeouts per hop (client, gateway, upstream)

- document caching behavior and preserve cache-relevant headers

Layers are a feature when the system stays observable and predictable.