Sep 20, 2025·8 min

SAP ERP as System of Record: Why Migrations Become Moats

SAP made ERP the trusted system of record for global firms. See why migrations—data, process, and people—create a durable competitive moat.

SAP made ERP the trusted system of record for global firms. See why migrations—data, process, and people—create a durable competitive moat.

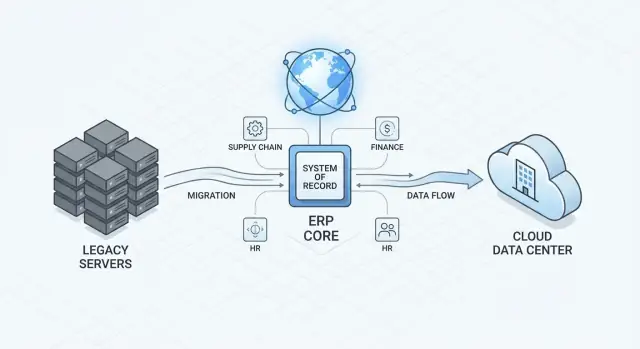

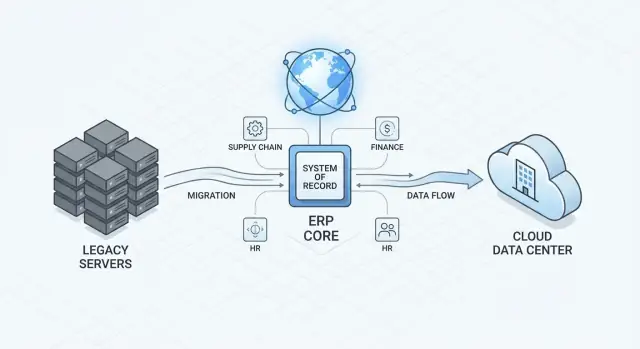

A system of record is the place your company treats as the official truth for critical business facts—customers, products, prices, orders, invoices, inventory, employees, and the rules that govern them. If two systems disagree, the system of record is the one that “wins.”

That matters because leadership decisions, audits, and day-to-day operations all depend on consistent answers to basic questions: What did we sell? To whom? At what margin? What do we owe? What do we have on hand? When those answers vary by region or tool, the organization spends its energy reconciling data instead of running the business.

SAP earned this role in many global enterprises because it sits at the intersection of finance, supply chain, and operations—the parts of the business where accuracy and controls are non-negotiable. Over time, companies built policies, approvals, and compliance routines around SAP data and transactions. Once that happens, SAP isn’t “just software”; it becomes the backbone that other systems reference.

The competitive advantage isn’t the license. The advantage is the organizational capability to migrate—to move data, redesign processes, integrate systems, and bring people along without breaking the business. If you can modernize your ERP faster and safer than peers, you can adopt new operating models, acquisitions, and regulatory requirements with less friction.

This is not a vendor history lesson. It’s a practical set of lessons for leaders: where migrations really fail, where the work really sits, and how to prepare.

The examples are SAP-centric, but the patterns apply to other major ERPs: once an ERP becomes your system of record, change becomes a capability you either build—or pay for later.

ERP didn’t start as the “brain” of the company. Early ERP programs were often justified as finance and accounting upgrades: better ledgers, faster closes, cleaner reporting. But once finance data became structured and reliable, it was natural to connect the activities that create those numbers—purchasing, production, shipping, service, and payroll.

Over time, ERP expanded from recording transactions to coordinating work. A purchase order is no longer just paperwork; it triggers approvals, updates budgets, reserves inventory, schedules receipts, and ultimately flows into accounts payable. The same pattern repeats across order-to-cash, hire-to-retire, and plan-to-produce.

Standardization is what made that expansion scalable. Large enterprises standardized on:

As ERP became the system of record, trust became the real product. Leaders rely on ERP because it supports auditability and controls: who approved what, when changes were made, which policy was applied, and how each operational event affects financial results. When the ERP is well-run, there’s a single version of key numbers—revenue, margin, inventory value, headcount—that can withstand scrutiny.

That consistency isn’t free. Central templates, shared master data, and standardized processes reduce local autonomy. A plant or country team may feel constrained when a global model doesn’t match local habits or regulations.

The best ERP programs treat this as an explicit design choice: standardize what must be comparable and controlled, and allow flexibility where it drives real customer value or compliance. That balance is what turns ERP from “software” into an operating system.

Global companies didn’t standardize on SAP because it was “one size fits all.” They did it because SAP could be made consistent enough to run the business globally, while still allowing local variation where regulations, tax, or operating models demand it.

Enterprises with dozens of business units face a repeatable problem: every country and product line needs the same core disciplines (order-to-cash, procure-to-pay, record-to-report), but none of them run exactly the same way.

SAP’s appeal has been its ability to support common process templates—shared definitions for customers, products, pricing, invoices, approvals—while configuring country- and industry-specific requirements (tax, currency, reporting, documentation). That balance enables standardization without forcing every site into identical day-to-day steps.

When ERP, finance, procurement, manufacturing, and logistics run in separate systems, teams spend a surprising amount of time on handoffs: re-keying data, reconciling totals, chasing mismatched status updates, and explaining “why system A says shipped but system B says not billed.”

Standardizing on SAP often reduced the number of these seams. Fewer handoffs typically means fewer reconciliation cycles, clearer ownership of data, and faster root-cause analysis when something goes wrong. It’s not automatic—but it’s a repeatable pattern when integration replaces manual bridges.

Large enterprises also need control: segregation of duties, approval chains, audit trails, and compliance checks.

SAP supports governance by design—roles and authorizations, workflow approvals for purchasing and payments, and process controls that can be enforced consistently across regions. The benefit isn’t “perfect compliance”; it’s the ability to operationalize policies inside the systems people actually use.

An ERP migration isn’t just “moving data” from one system to another. It’s a coordinated change to how the business runs: redesigned processes, rebuilt integrations, updated controls and reporting, revised security roles, and training that makes new behaviors stick. The data cutover weekend is simply the most visible moment of a much longer transformation.

Two companies can buy the same ERP software and still face completely different migration effort. Your product catalog, pricing rules, approval paths, regulatory obligations, acquisition history, and custom interfaces create a unique web of dependencies. Migrating means translating that reality into a new set of configurations, integrations, and governance routines without breaking operations.

That work is difficult to copy because it’s embedded in how your company actually functions. Competitors can see your end result—faster close, cleaner master data, fewer manual workarounds—but they can’t easily replicate the knowledge you built while untangling exceptions, reconciling definitions, and aligning teams.

The first major ERP migration forces you to learn where the organization is unclear: who owns customer master data, which reports are trusted, which controls are real versus “tribal,” and which integrations are undocumented. After you’ve gone through it once, you tend to have better templates, clearer decision rights, and reusable integration patterns.

The second migration is often faster and safer not because the technology is easier, but because your organization is better.

When migrations become repeatable—supported by strong data ownership, testing discipline, and change management—you gain strategic flexibility. You can integrate acquisitions faster, adopt innovations like S/4HANA more confidently, and modernize without stalling the business. That capability is a competitive moat you build by doing the hard work well.

ERP migrations rarely happen because a company wakes up and “feels like modernizing.” They stay on the roadmap because the business keeps changing—and SAP sits at the center of how finance, supply chain, and operations are recorded.

A migration program is often pulled forward by events that change what the system must support:

These triggers aren’t edge cases—they’re normal for global companies. That’s why “we’ll migrate later” often turns into “we’re migrating during a crisis.”

When migration is postponed, organizations compensate with stopgaps: parallel systems, bolt-on tools, extra reconciliations, and spreadsheet-heavy workarounds. The result isn’t just IT complexity—it’s slower closes, slower reporting, and more time spent explaining numbers instead of acting on them.

Delays also compound data problems. The longer master data issues linger, the more downstream processes depend on exceptions and manual fixes.

Even when the decision is made, the calendar can make or break the outcome. Peak seasons, year-end close, major product launches, and planned facility shutdowns all create “no-fly zones.” On top of that, the same people needed for migration—finance SMEs, supply chain leads, integration owners—are often the people you can least spare.

Because change is constant, the advantage shifts to companies that build repeatable migration capability: clear ownership of data, disciplined integration patterns, and governance that can absorb reorganizations without resetting the whole plan. Migration stops being a one-off project and becomes part of how the business stays adaptable.

ERP migrations rarely fail because of the software. They stall because the organization can’t agree on what its data means, who owns it, and how clean it needs to be before it moves.

Think of transactional data as the “events” your business records every day: sales orders, invoices, goods receipts, time entries, payments. These are high-volume and time-stamped.

Master data is the “shared reference” those events rely on: customer records, vendor records, materials/products, bills of material, plants, cost centers, pricing conditions, chart of accounts. In SAP ERP, master data is what makes transactions comparable and reportable across teams and regions.

A simple example: an invoice (transaction) is only as accurate as the customer master record (master data) it points to—address, tax ID, payment terms, credit limits.

Most enterprises discover the same issues during an ERP migration:

Data cleansing isn’t an IT clean-up project; it’s a business decision. Data owners (often in finance, sales ops, supply chain, procurement) must define standards: what fields are mandatory, how naming works, what the golden record is, and which team approves changes.

When ownership is unclear, quality stays subjective—and that has real outcomes: weaker forecasting, slower quote-to-cash, inconsistent customer experiences, and compliance risk when audits rely on incomplete or conflicting records.

A new SAP system can be technically “live” and still feel broken if day-to-day processes and integrations haven’t been rebuilt with care. Most migration pain shows up here: orders that can’t flow end-to-end, approvals that bypass controls, or reports that no longer match operational reality.

Many legacy ERPs accumulated years of custom code to handle edge cases, local variations, and “that’s how we’ve always done it.” Modern SAP programs increasingly follow a clean core approach: keep SAP closer to standard, push extensions to well-defined layers, and reduce changes that make upgrades harder.

This doesn’t mean “no customization.” It means being deliberate: if a customization doesn’t clearly protect revenue, compliance, or a true competitive advantage, it’s a candidate for redesign or retirement.

Standardizing finance, procurement basics, and common supply chain steps usually pays back quickly: shared data definitions, fewer exceptions, easier training, and simpler global reporting.

Save differentiation for places where customers notice and value it—pricing logic, fulfillment promises, after-sales service, or product configuration. The practical test is: If we copied a standard process here, would our market position change? If not, standardize.

Legacy integrations often rely on brittle point-to-point connections and batch files. Modern integration is more like building reliable “connectors” between systems:

The goal isn’t novelty—it’s fewer breaks, clearer ownership, and faster change.

In practice, teams often need lightweight “surrounding apps” too—internal portals for cutover tracking, data quality queues, exception triage dashboards, or role-based task checklists. Platforms like Koder.ai can help you spin up those supporting tools quickly via a chat-based workflow (with exportable source code), so the migration program isn’t blocked waiting on a long custom dev cycle for every small but critical capability.

Controls can’t be bolted on after go-live. Approval steps, segregation of duties, logging, and reconciliations need to be built into workflows and integrations from the start. Otherwise, you get “shadow processes” in email and spreadsheets—exactly where auditability disappears.

Treat every integration like a financial transaction: who changed what, when, and why should be traceable by design.

Most ERP programs don’t fail because the software can’t be configured. They fail because the organization can’t make (and stick to) the decisions required to change how work gets done.

Three patterns show up repeatedly:

Successful migrations name specific owners for outcomes, not just tasks:

Users don’t resist “SAP”; they resist surprises. A migration changes jobs: new approvals, new handoffs, new exception handling, and new metrics that expose delays or rework. Training should be role-based and scenario-driven (what to do when things go wrong), and it must include managers who interpret the new dashboards and enforce the new rules.

Set a cadence that forces progress:

When people and governance are handled well, technical complexity becomes manageable—and the migration becomes a capability, not a one-time event.

An ERP migration isn’t a beauty contest. A realistic goal is to reduce risk and accelerate time-to-value—getting the business onto a stable, supportable platform with clean data and working processes—rather than chasing a “perfect” redesign everywhere at once.

Big-bang (single cutover): You switch all sites, processes, and users to the new system at once.

Phased rollout (by region, business unit, or process): You move in stages.

Selective data migration (selective historical scope): You move only what you need—often open items plus a defined history window.

Treat testing as a progressive funnel:

Choose your path by scoring each major area on:

The “right” strategy is the one that matches your operational risk tolerance and your organization’s capacity to absorb change—while keeping the scope tight enough to deliver a real milestone, not an endless program.

Moving from a classic SAP ERP setup to S/4HANA (and especially to cloud-hosted ERP) isn’t just a technical upgrade. It changes how fast you can adopt new capabilities, how much you can tailor the system, and what “good governance” needs to look like day to day.

S/4HANA is built to work with a simplified data model and an in-memory database. For business teams, that typically means faster reporting and more consistent real-time views (for example, inventory, finance, and order status aligning more cleanly).

Cloud hosting adds another shift: SAP (and your cloud provider) takes on more of the platform work—patching, scaling, and infrastructure operations—so your team can focus more on processes, data, and change.

The trade-off is straightforward:

Even in cloud ERP, security is still your responsibility in key areas:

“Go-live” doesn’t end the job. Integrations still need monitoring, change coordination, and version management. And data still needs ownership: master data standards, quality rules, and accountability when definitions drift. The platform may modernize—your operating discipline still has to mature.

Treat readiness as a gate, not a feeling. Before you commit to an ERP migration plan (especially an S/4HANA migration), align on what “ready” means in concrete, testable terms.

Too many custom objects with unclear business value, unknown interfaces (“we’ll find them in testing”), and weak data ownership (“IT will fix the data”) are top indicators your timeline is fiction.

Pick a small set of outcomes and baseline them now: financial close time, order cycle time, inventory accuracy, and user adoption (task completion rates, ticket volume by process).

Plan hypercare (clear triage, daily business checkpoints), a prioritized backlog (what didn’t make go-live), and a continuous improvement cadence with owners and KPIs—so the system gets better instead of merely “staying up.”

SAP earned its place as a system of record because it makes critical enterprise facts—orders, inventory, invoices, payroll, compliance evidence—consistent enough to run a global business. But the long-term advantage isn’t only having SAP. It’s being able to change SAP safely and repeatedly while others stall.

ERP migrations concentrate the hardest work in one place: data, process, integrations, and people. When your organization can modernize without breaking operations, you can adopt better processes, retire legacy costs, and respond faster to regulatory or market shifts. That capability compounds over time—each migration teaches you patterns, reduces uncertainty, and shortens the next cycle.

The best teams build reusable playbooks:

These aren’t one-off artifacts. They’re operational muscle.

Start by mapping your current complexity: number of interfaces, custom code hotspots, data domains with unclear ownership, and business processes that vary by region. Then prioritize migrations that unlock the most value—high-risk legacy platforms, costly integrations, or areas where data quality blocks automation.

As you do this, consider where small, purpose-built internal tools could remove friction (for example: data stewardship workflows, interface monitoring, UAT triage, cutover runbooks, or hypercare ticket routing). Building those “migration accelerators” doesn’t have to mean a long backlog—teams increasingly use platforms like Koder.ai to create and iterate on these apps quickly from a chat interface, then export the code when they need deeper control or enterprise deployment.

Migrations are hard. They demand patience, governance, and unglamorous detail. But once your organization can execute them predictably, that competence becomes durable—and it shows up as speed, resilience, and confidence when the next change arrives.

A system of record is the authoritative source for key business facts (customers, products, prices, orders, invoices, inventory, employees). When two systems disagree, the system of record is the one you treat as “right” for operations, audits, and reporting.

A practical test: if a dispute arises, which system’s data gets corrected—and which system gets updated to match?

SAP often sits at the intersection of finance, supply chain, and operations—areas where controls, auditability, and standardized definitions matter most.

Over time, policies (approvals, segregation of duties, compliance routines) get embedded into SAP workflows, making SAP the reference point other systems must align to.

Owning a repeatable migration capability lets you modernize processes, integrate acquisitions, and respond to regulatory change faster—without breaking daily operations.

Software can be purchased; the organizational know-how to clean data, redesign processes, rebuild integrations, and execute cutovers safely is much harder for competitors to copy.

Common triggers include:

These events force changes in the system that records financial and operational truth.

Master data is the shared reference (customers, vendors, materials, chart of accounts, cost centers, pricing conditions). Transactional data is the daily events (orders, invoices, receipts, payments).

Migrations often bottleneck on master data because bad references create bad transactions in the new system. Fixing master data also requires business decisions (definitions, ownership), not just technical cleanup.

Start with business-owned rules and accountability:

If “IT will fix the data” is the plan, timelines usually slip.

A clean core approach keeps SAP closer to standard and moves differentiating logic to controlled extensions (configuration, side-by-side apps, stable interfaces).

Benefits:

It doesn’t mean “no customization”—it means customizing only where it protects revenue, compliance, or real competitive advantage.

Prioritize integration clarity and reliability:

Treat each integration like a financial control: traceable, testable, and observable.

Choose based on operational risk tolerance and readiness:

A simple decision method: score each area by criticality, readiness (data/process/people), and dependencies (interfaces/regulations/calendar).

Minimum signals of readiness include:

For stabilization, plan hypercare with clear triage, daily business checkpoints, and a prioritized post–go-live backlog so the system improves rather than merely “stays up.”