Nov 10, 2025·8 min

Schema Changes and Migrations in AI-Built Systems: A Guide

Learn how AI-built systems handle schema changes safely: versioning, backward-compatible rollouts, data migrations, testing, observability, and rollback strategies.

What “Schema” Means in AI-Built Systems

A schema is simply the shared agreement about the shape of data and what each field means. In AI-built systems, that agreement shows up in more places than just database tables—and it changes more often than teams expect.

Schema isn’t just a database thing

You’ll run into schemas in at least four common layers:

- Databases: table/column names, data types, constraints, indexes, and relationships.

- APIs: request/response JSON shape, required vs. optional fields, enums, error formats, pagination conventions.

- Events and messages: the payloads sent through streams, queues, and webhooks (often versioned implicitly through consumers).

- Configs and contracts: feature flags, environment variables, YAML/JSON configs, and “hidden contracts” like file formats and naming conventions.

If two parts of the system exchange data, there’s a schema—even if nobody wrote it down.

Why AI-built systems see schema changes more often

AI-generated code can drastically accelerate development, but it also increases churn:

- Generated code reflects the latest prompt and context, so small prompt tweaks can change field names, nesting, defaults, or validations.

- Requirements evolve faster when it’s cheap to ship a new endpoint or pipeline step.

- Inconsistent conventions (snake_case vs. camelCase,

idvs.userId) pop up when multiple generations or refactors happen across teams.

The result is more frequent “contract drift” between producers and consumers.

If you’re using a vibe-coding workflow (for example, generating handlers, DB access layers, and integrations through chat), it’s worth baking schema discipline into that workflow from day one. Platforms like Koder.ai help teams move quickly by generating React/Go/PostgreSQL and Flutter apps from a chat interface—but the faster you can ship, the more important it becomes to version interfaces, validate payloads, and roll changes out deliberately.

The goal of this guide

This post focuses on practical ways to keep production stable while still iterating quickly: maintaining backward compatibility, rolling out changes safely, and migrating data without surprises.

What we won’t cover

We won’t dive deep into theory-heavy modeling, formal methods, or vendor-specific features. The emphasis is on patterns you can apply across stacks—whether your system is hand-coded, AI-assisted, or mostly AI-generated.

Why Schema Changes Happen More Often with AI-Generated Code

AI-generated code tends to make schema changes feel “normal”—not because teams are careless, but because the inputs to the system change more frequently. When your application behavior is partially driven by prompts, model versions, and generated glue code, the shape of data is more likely to drift over time.

Common triggers you’ll see in practice

A few patterns repeatedly cause schema churn:

- New product features: adding a new field (e.g.,

risk_score,explanation,source_url) or splitting one concept into many (e.g.,addressintostreet,city,postal_code). - Model output changes: a newer model might produce more detailed structures, different enum values, or slightly different naming (“confidence” vs. “score”).

- Prompt updates: prompt tweaks meant to improve quality can unintentionally change formatting, required fields, or nesting.

Risky patterns that make AI systems brittle

AI-generated code often “works” quickly, but it can encode fragile assumptions:

- Implicit assumptions: code quietly assumes a field is always present, always numeric, or always within a certain range.

- Hidden coupling: one service relies on another service’s internal field names or ordering instead of a defined interface.

- Undocumented fields: the model starts emitting a new property, and downstream code begins to rely on it without anyone explicitly agreeing it’s part of the contract.

Why AI amplifies change frequency

Code generation encourages rapid iteration: you regenerate handlers, parsers, and database access layers as requirements evolve. That speed is useful, but it also makes it easy to ship small interface changes repeatedly—sometimes without noticing.

The safer mindset is to treat every schema as a contract: database tables, API payloads, events, and even structured LLM responses. If a consumer depends on it, version it, validate it, and change it deliberately.

Types of Schema Changes: Additive vs. Breaking

Schema changes aren’t all equal. The most useful first question is: will existing consumers keep working without any changes? If yes, it’s usually additive. If no, it’s breaking—and needs a coordinated rollout plan.

Additive changes (usually safe)

Additive changes extend what’s already there without changing existing meaning.

Common database examples:

- Add a column with a default or allow NULLs (e.g.,

preferred_language). - Add a new table or index.

- Add an optional field to a JSON blob stored in a column.

Non-database examples:

- Add a new property to an API response (clients that ignore unknown fields keep working).

- Add a new event field in a stream/queue message.

- Add a new feature flag value while keeping existing behavior as the default.

Additive is only “safe” if older consumers are tolerant: they must ignore unknown fields and not require new ones.

Breaking changes (risky)

Breaking changes alter or remove something consumers already depend on.

Typical database breaking changes:

- Change a column type (string → integer, timestamp precision changes).

- Rename a field/column (everything reading the old name fails).

- Drop a column/table that is still queried.

Non-database breaking changes:

- Rename/remove JSON fields in request/response payloads.

- Change event semantics (same field name, different meaning).

- Modify webhook payload structure without a version bump.

Always write down consumer impact

Before merging, document:

- Who consumes it (services, dashboards, data pipelines, partners).

- Compatibility (backward/forward, and for how long).

- Failure mode (parsing errors, silent data corruption, wrong business logic).

This short “impact note” forces clarity—especially when AI-generated code introduces schema changes implicitly.

Versioning Strategies for Schemas and Interfaces

Versioning is how you tell other systems (and future you) “this changed, and here’s how risky it is.” The goal isn’t paperwork—it’s preventing silent breakage when clients, services, or data pipelines update at different speeds.

A plain-language semantic versioning mindset

Think in major / minor / patch terms, even if you don’t literally publish 1.2.3:

- Major: breaking change. Old consumers may fail or misbehave without changes.

- Minor: safe addition. Old consumers still work; new consumers can use new capabilities.

- Patch: bug fix or clarification that doesn’t change meaning.

A simple rule that saves teams: never change the meaning of an existing field silently. If status="active" used to mean “paying customer,” don’t repurpose it to mean “account exists.” Add a new field or a new version.

Versioned endpoints vs. versioned fields

You usually have two practical options:

1) Versioned endpoints (e.g., /api/v1/orders and /api/v2/orders):

Good when changes are truly breaking or widespread. It’s clear, but it can create duplication and long-lived maintenance if you keep multiple versions around.

2) Versioned fields / additive evolution (e.g., add new_field, keep old_field):

Good when you can make changes additively. Older clients ignore what they don’t understand; newer clients read the new field. Over time, deprecate and remove the old field with an explicit plan.

Event schemas and registries

For streams, queues, and webhooks, consumers are often outside your deployment control. A schema registry (or any centralized schema catalog with compatibility checks) helps enforce rules like “only additive changes allowed” and makes it obvious which producers and consumers rely on which versions.

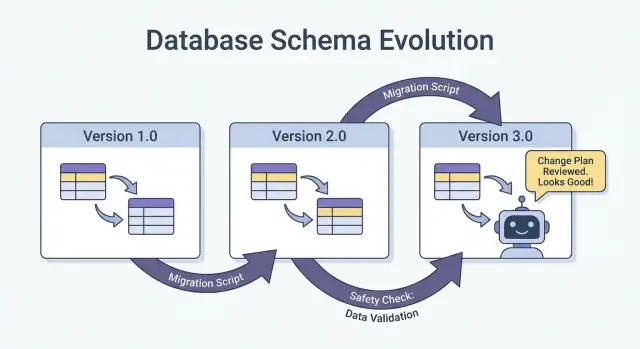

Safe Rollouts: Expand/Contract (The Most Reliable Pattern)

The safest way to ship schema changes—especially when you have multiple services, jobs, and AI-generated components—is the expand → backfill → switch → contract pattern. It minimizes downtime and avoids “all-or-nothing” deployments where one lagging consumer breaks production.

The four steps (and why they work)

1) Expand: Introduce the new schema in a backward-compatible way. Existing readers and writers should continue working unchanged.

2) Backfill: Populate new fields for historical data (or reprocess messages) so the system becomes consistent.

3) Switch: Update writers and readers to use the new field/format. This can be done gradually (canary, percentage rollout) because the schema supports both.

4) Contract: Remove the old field/format only after you’re confident nothing depends on it.

Two-phase (expand → switch) and three-phase (expand → backfill → switch) rollouts reduce downtime because they avoid tight coupling: writers can move first, readers can move later, and vice versa.

Example: add a column, backfill, then make it required

Suppose you want to add customer_tier.

- Expand: Add

customer_tieras nullable with a default ofNULL. - Backfill: Run a job to compute tiers for existing rows.

- Switch: Update the app and pipelines to always write

customer_tier, and update readers to prefer it. - Contract: After monitoring, make it NOT NULL (and optionally drop legacy logic).

Coordination: writers and readers must agree

Treat every schema as a contract between producers (writers) and consumers (readers). In AI-built systems, this is easy to miss because new code paths appear quickly. Make rollouts explicit: document which version writes what, which services can read both, and the exact “contract date” when old fields can be removed.

Database Migrations: How to Change Data Without Breaking Production

Plan your next schema change

Use planning mode to map expand-backfill-switch-contract before you generate code.

Database migrations are the “instruction manual” for moving production data and structure from one safe state to the next. In AI-built systems, they matter even more because generated code can accidentally assume a column exists, rename fields inconsistently, or change constraints without considering existing rows.

Migration files vs. auto-migrations

Migration files (checked into source control) are explicit steps like “add column X,” “create index Y,” or “copy data from A to B.” They’re auditable, reviewable, and can be replayed in staging and production.

Auto-migrations (generated by an ORM/framework) are convenient for early development and prototyping, but they can produce risky operations (dropping columns, rebuilding tables) or reorder changes in ways you didn’t intend.

A practical rule: use auto-migrations to draft changes, then convert them to reviewed migration files for anything that touches production.

Idempotency and ordering

Make migrations idempotent where possible: re-running them should not corrupt data or fail halfway. Prefer “create if not exists,” add new columns as nullable first, and guard data transforms with checks.

Also keep a clear ordering. Every environment (local, CI, staging, prod) should apply the same migration sequence. Don’t “fix” production with manual SQL unless you capture it in a migration afterward.

Long-running migrations without locking the table

Some schema changes can block writes (or even reads) if they lock a large table. High-level ways to reduce risk:

- Use online/lock-minimizing operations supported by your database (e.g., concurrent index builds).

- Split changes into steps: add new structures first, backfill in batches, then switch the app.

- Schedule heavy operations during low-traffic windows, with timeouts and monitoring.

Multi-tenant and sharded setups

For multi-tenant databases, run migrations in a controlled loop per tenant, with progress tracking and safe retries. For shards, treat each shard like a separate production system: roll migrations shard-by-shard, verify health, then proceed. This limits blast radius and makes rollback feasible.

Backfills and Reprocessing: Updating Existing Data

A backfill is when you populate newly added fields (or corrected values) for existing records. Reprocessing is when you run historical data back through a pipeline again—typically because business rules changed, a bug was fixed, or a model/output format was updated.

Both are common after schema changes: it’s easy to start writing the new shape for “new data,” but production systems also depend on yesterday’s data being consistent.

Common approaches

Online backfill (in production, gradually). You run a controlled job that updates records in small batches while the system stays live. This is safer for critical services because you can throttle the load, pause, and resume.

Batch backfill (offline or scheduled jobs). You process large chunks during low-traffic windows. It’s simpler operationally, but can create spikes in database load and can take longer to recover from mistakes.

Lazy backfill on read. When an old record is read, the application calculates/populates the missing fields and writes it back. This spreads cost over time and avoids a big job, but it makes first-read slower and can leave “old” data unconverted for a long time.

In practice, teams often combine these: lazy backfill for long-tail records, plus an online job for the most frequently accessed data.

How to validate a backfill

Validation should be explicit and measurable:

- Counts: how many rows/events should be updated vs. how many were updated.

- Checksums/aggregates: compare totals (e.g., sum of amounts, distinct IDs) before/after.

- Sampling: spot-check a statistically meaningful sample, including edge cases.

Also validate downstream effects: dashboards, search indexes, caches, and any exports that rely on the updated fields.

Cost, time, and acceptance criteria

Backfills trade speed (finish quickly) against risk and cost (load, compute, and operational overhead). Set acceptance criteria up front: what “done” means, expected runtime, maximum allowed error rate, and what you’ll do if validation fails (pause, retry, or roll back).

Event and Message Schema Evolution (Streams, Queues, Webhooks)

Turn contracts into code

Generate APIs and DB layers, then iterate safely with versioned interfaces.

Schemas don’t live only in databases. Any time one system sends data to another—Kafka topics, SQS/RabbitMQ queues, webhook payloads, even “events” written to object storage—you’ve created a contract. Producers and consumers move independently, so these contracts tend to break more often than a single app’s internal tables.

The safest default: evolve events backward-compatibly

For event streams and webhook payloads, prefer changes that old consumers can ignore and new consumers can adopt.

A practical rule: add fields, don’t remove or rename. If you must deprecate something, keep sending it for a while and document it as deprecated.

Example: extend an OrderCreated event by adding optional fields.

{

"event_type": "OrderCreated",

"order_id": "o_123",

"created_at": "2025-12-01T10:00:00Z",

"currency": "USD",

"discount_code": "WELCOME10"

}

Older consumers read order_id and created_at and ignore the rest.

Consumer-driven contracts (plain-English version)

Instead of the producer guessing what might break others, consumers publish what they rely on (fields, types, required/optional rules). The producer then validates changes against those expectations before shipping. This is especially useful in AI-generated codebases, where a model might “helpfully” rename a field or change a type.

Handling “unknown fields” safely

Make parsers tolerant:

- Ignore unknown fields by default (don’t fail just because a new key appears).

- Treat new fields as optional until you truly need them.

- Log unexpected fields at a low level so you can spot adoption issues without paging.

When you need a breaking change, use a new event type or versioned name (for example OrderCreated.v2) and run both in parallel until all consumers migrate.

AI Outputs as a Schema: Prompts, Models, and Structured Responses

When you add an LLM to a system, its outputs quickly become a de facto schema—even if nobody wrote a formal spec. Downstream code starts to assume “there will be a summary field,” “the first line is the title,” or “bullets are separated by dashes.” Those assumptions harden over time, and a small shift in model behavior can break them just like a database column rename.

Prefer explicit structure (and validate it)

Instead of parsing “pretty text,” ask for structured outputs (typically JSON) and validate them before they enter the rest of your system. Think of this as moving from “best effort” to a contract.

A practical approach:

- Define a JSON schema (or a typed interface) for the model response.

- Reject or quarantine invalid responses (don’t silently coerce them).

- Log validation errors so you can see what’s changing.

This is especially important when LLM responses feed data pipelines, automation, or user-facing content.

Plan for model drift

Even with the same prompt, outputs can shift over time: fields may be omitted, extra keys may appear, and types can change ("42" vs 42, arrays vs. strings). Treat these as schema evolution events.

Mitigations that work well:

- Make fields optional where reasonable, and set defaults explicitly.

- Allow unknown keys but ignore them safely (unless you’re strict for compliance reasons).

- Add “guardrails” checks (e.g., required fields, max lengths, enum values).

Treat prompt changes like API changes

A prompt is an interface. If you edit it, version it. Keep prompt_v1, prompt_v2, and roll out gradually (feature flags, canaries, or per-tenant toggles). Test with a fixed evaluation set before promoting changes, and keep older versions running until downstream consumers have adapted. For more on safe rollout mechanics, link your approach to /blog/safe-rollouts-expand-contract.

Testing and Validation for Schema Changes

Schema changes usually fail in boring, expensive ways: a new column is missing in one environment, a consumer still expects an old field, or a migration runs fine on empty data but times out in production. Testing is how you turn those “surprises” into predictable, fixable work.

Three levels of tests (and what each catches)

Unit tests protect local logic: mapping functions, serializers/deserializers, validators, and query builders. If a field is renamed or a type changes, unit tests should fail close to the code that needs updating.

Integration tests ensure your app still works with real dependencies: the actual database engine, a real migration tool, and real message formats. This is where you catch issues like “the ORM model changed but the migration didn’t,” or “the new index name conflicts.”

End-to-end tests simulate user or workflow outcomes across services: create data, migrate it, read it back through APIs, and verify downstream consumers still behave correctly.

Contract tests for producers and consumers

Schema evolution often breaks at boundaries: service-to-service APIs, streams, queues, and webhooks. Add contract tests that run on both sides:

- Producers prove they can emit events/responses that match an agreed contract.

- Consumers prove they can still parse both the old and new versions during a rollout.

Migration testing: apply and rollback on fresh environments

Test migrations like you deploy them:

- Start from a clean database snapshot.

- Apply all migrations in order.

- Verify the app can read/write.

- Run a rollback (if supported) or a “down” migration and confirm it returns to a working state.

Fixtures for old and new schema versions

Keep a small set of fixtures representing:

- Data written under the previous schema (legacy rows/events).

- Data written under the new schema.

These fixtures make regressions obvious, especially when AI-generated code subtly changes field names, optionality, or formatting.

Observability: Detecting Breakage Early

Build with schema discipline

Build a React, Go, and PostgreSQL app in chat while keeping schemas and migrations explicit.

Schema changes rarely fail loudly at the exact moment you deploy them. More often, breakage shows up as a slow rise in parsing errors, odd “unknown field” warnings, missing data, or background jobs falling behind. Good observability turns those weak signals into actionable feedback while you can still pause the rollout.

What to monitor during a rollout

Start with the basics (app health), then add schema-specific signals:

- Errors: spikes in 4xx/5xx, but also “soft” errors like JSON parsing failures, failed deserialization, and retries.

- Latency: p95/p99 response times and queue processing time. Schema changes can add joins, bigger payloads, or extra validation.

- Data quality signals: null-rate increases in important columns, sudden drops in event volume, new “default” values appearing too often, or mismatches between old and new representations.

- Pipeline lag: consumer lag in streams/queues, webhook delivery backlog, and migration job throughput.

The key is to compare before vs. after and to slice by client version, schema version, and traffic segment (canary vs. stable).

Dashboards that actually help

Create two dashboard views:

-

Application behavior dashboard

- Request rate, error rate, latency (RED)

- Top exceptions (grouped by message)

- Validation/parsing error count and percentage

- Payload size distribution (to catch unexpectedly large messages)

-

Migration and background job dashboard

- Migration job progress (% complete), rows processed/sec, ETA

- Failure rate and retry count

- Queue depth / consumer lag

- Dead-letter queue volume (if applicable)

If you run an expand/contract rollout, include a panel that shows reads/writes split by old vs. new schema so you can see when it’s safe to move to the next phase.

Alerts for schema-specific failures

Page on issues that indicate data is being dropped or misread:

- Schema validation error rate above a low threshold (often <0.1% is already meaningful)

- Parsing/deserialization failures (especially if concentrated in one producer/consumer)

- Unexpected field / missing required field warnings that trend upward

- Migration job stalled (no progress for N minutes) or lag growing faster than throughput

Avoid noisy alerts on raw 500s without context; tie alerts to the schema rollout using tags like schema version and endpoint.

Log the version so you can debug fast

During the transition, include and log:

- Schema version (e.g.,

X-Schema-Versionheader, message metadata field) - Producer and consumer app version

- Model version / prompt version when AI-generated outputs feed structured data

That one detail makes “why did this payload fail?” answerable in minutes, not days—especially when different services (or different AI model versions) are live at the same time.

Rollback, Recovery, and Change Management

Schema changes fail in two ways: the change itself is wrong, or the system around it behaves differently than expected (especially when AI-generated code introduces subtle assumptions). Either way, every migration needs a rollback story before it ships—even if that story is explicitly “no rollback.”

Choosing “no rollback” can be valid when the change is irreversible (for example, dropping columns, rewriting identifiers, or deduplicating records in a destructive way). But “no rollback” isn’t the absence of a plan; it’s a decision that shifts the plan toward forward fixes, restores, and containment.

Practical rollback options that actually work

Feature flags / config gates: Wrap new readers, writers, and API fields behind a flag so you can turn off the new behavior without redeploying. This is especially useful when AI-generated code may be correct syntactically but wrong semantically.

Disable dual-write: If you’re writing to old and new schemas during an expand/contract rollout, keep a kill switch. Turning off the new write path stops further divergence while you investigate.

Revert readers (not just writers): Many incidents happen because consumers start reading new fields or new tables too early. Make it easy to point services back to the previous schema version, or to ignore new fields.

Know the limits of reversibility

Some migrations can’t be cleanly undone:

- Destructive transformations (e.g., hashing, lossy normalization).

- Drops/renames without a preserved copy.

- Backfills that overwrite “source of truth” values.

For these, plan for restore-from-backup, replay from events, or recompute from raw inputs—and verify you still have those inputs.

Pre-flight checklist (before shipping)

- Rollback decision documented (“revert,” “forward fix,” or “no rollback + restore path”).

- Clear stop button: flags and/or dual-write disable switch.

- Backups/snapshots verified; restore tested at least once.

- Migration is idempotent; reruns won’t corrupt data.

- Monitoring and alerts for error rates, schema validation failures, and lag.

- Ownership: who approves, who runs, who is on-call during rollout.

Good change management makes rollbacks rare—and makes recovery boring when they do happen.

If your team is iterating quickly with AI-assisted development, it helps to pair these practices with tooling that supports safe experimentation. For example, Koder.ai includes planning mode for upfront change design and snapshots/rollback for fast recovery when a generated change accidentally shifts a contract. Used together, rapid code generation and disciplined schema evolution let you move faster without treating production as a test environment.