May 18, 2025·8 min

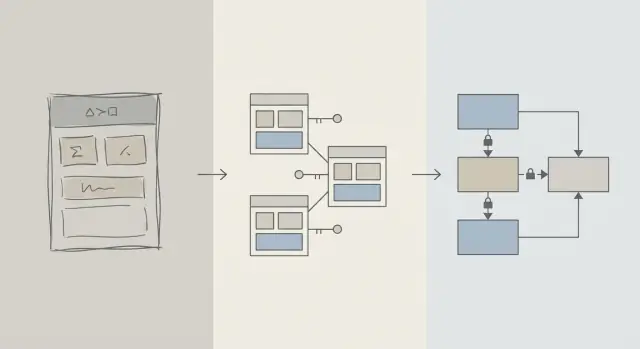

Schema Design First: Faster Apps Than Early Query Tuning

Early performance wins usually come from better schema design: the right tables, keys, and constraints prevent slow queries and costly rewrites later.

Schema vs Query Optimization: What We Mean

When an app feels slow, the first instinct is often to “fix the SQL.” That urge makes sense: a single query is visible, measurable, and easy to blame. You can run EXPLAIN, add an index, tweak a JOIN, and sometimes see an immediate win.

But early in a product’s life, speed problems are just as likely to come from the shape of the data as from the specific query text. If the schema forces you to fight the database, query tuning turns into a cycle of whack-a-mole.

Schema design (plain English)

Schema design is how you organize your data: tables, columns, relationships, and rules. It includes decisions like:

- What “things” deserve their own table (users, orders, events)

- How tables relate (one-to-many, many-to-many)

- What must be unique or required (constraints)

- How you represent states and history (timestamps, status fields, audit records)

Good schema design makes the natural way of asking questions also the fast way.

Query optimization (plain English)

Query optimization is improving how you fetch or update data: rewriting queries, adding indexes, reducing unnecessary work, and avoiding patterns that trigger huge scans.

Both matter—timing matters more

This article isn’t “schema good, queries bad.” It’s about order of operations: get the fundamentals of the database schema right first, then tune the queries that truly need it.

You’ll learn why schema decisions dominate early performance, how to spot when the schema is the real bottleneck, and how to evolve it safely as your app grows. This is written for product teams, founders, and developers building real-world apps—not database specialists.

Why Schema Design Drives Most Early Performance

Early performance usually isn’t about clever SQL—it’s about how much data the database is forced to touch.

Structure determines how much you scan

A query can only be as selective as the data model allows. If you store “status”, “type”, or “owner” in loosely structured fields (or spread across inconsistent tables), the database often has to scan far more rows to figure out what matches.

A good schema narrows the search space naturally: clear columns, consistent data types, and well-scoped tables mean queries filter earlier and read fewer pages from disk or memory.

Missing keys create expensive work

When primary keys and foreign keys are missing (or not enforced), relationships become guesses. That pushes work into the query layer:

- Joins get larger because there’s no reliable, indexed join path.

- Filters get more complex because you’re compensating for duplicates, nulls, and “almost matching” values.

Without constraints, bad data accumulates—so queries keep getting slower as you add more rows.

Indexes follow the schema (and can’t fix everything)

Indexes are most useful when they match predictable access paths: joining by foreign keys, filtering by well-defined columns, sorting by common fields. If the schema stores critical attributes in the wrong table, mixes meanings in one column, or relies on text parsing, indexes can’t rescue you—you’re still scanning and transforming too much.

Fast by default

With clean relationships, stable identifiers, and sensible table boundaries, many everyday queries become “fast by default” because they touch less data and use simple, index-friendly predicates. Query tuning then becomes a finishing step—not a constant firefight.

The Early-Stage Reality: Change Is Constant

Early-stage products don’t have “stable requirements”—they have experiments. Features ship, get rewritten, or disappear. A small team is juggling roadmap pressure, support, and infrastructure with limited time to revisit old decisions.

What changes most often

It’s rarely the SQL text that changes first. It’s the meaning of the data: new states, new relationships, new “oh, we also need to track…” fields, and whole workflows that weren’t imagined at launch. That churn is normal—and it’s exactly why schema choices matter so much early on.

Why fixing schema later is harder than fixing a query

Rewriting a query is usually reversible and local: you can ship an improvement, measure it, and roll back if needed.

Rewriting a schema is different. Once you’ve stored real customer data, every structural change turns into a project:

- Migrations that lock tables or slow writes at peak times

- Backfills to populate new columns or rebuild derived data

- Dual-write or shadow tables to keep the app running during a transition

- Downtime risk if a change can’t be done online

Even with good tooling, schema changes introduce coordination costs: app code updates, deployment sequencing, and data validation.

How early decisions compound

When the database is small, a clumsy schema can look “fine.” As rows grow from thousands to millions, the same design creates larger scans, heavier indexes, and more expensive joins—then every new feature builds on top of that foundation.

So the early-stage goal isn’t perfection. It’s choosing a schema that can absorb change without forcing risky migrations every time the product learns something new.

Design Fundamentals That Prevent Slow Queries

Most “slow query” problems at the beginning aren’t about SQL tricks—they’re about ambiguity in the data model. If the schema makes it unclear what a record represents, or how records relate, every query becomes more expensive to write, run, and maintain.

Start with a small set of core entities

Begin by naming the few things your product cannot function without: users, accounts, orders, subscriptions, events, invoices—whatever is truly central. Then define relationships explicitly: one-to-many, many-to-many (usually with a join table), and ownership (who “contains” what).

A practical check: for each table, you should be able to complete the sentence “A row in this table represents ___.” If you can’t, the table is likely mixing concepts, which later forces complex filtering and joins.

Make naming and ownership boringly consistent

Consistency prevents accidental joins and confusing API behavior. Pick conventions (snake_case vs camelCase, *_id, created_at/updated_at) and stick to them.

Also decide who owns a field. For example, “billing_address” belongs to an order (snapshot in time) or to a user (current default)? Both can be valid—but mixing them without clear intent creates slow, error-prone queries to “figure out the truth.”

Choose data types that match reality

Use types that avoid runtime conversions:

- Use timestamps with time zone rules you understand.

- Use decimals for money (not floats).

- Use enums/reference tables for known categories.

When types are wrong, databases can’t compare efficiently, indexes become less useful, and queries often need casting.

Don’t duplicate facts without a plan

Storing the same fact in multiple places (e.g., order_total and sum(line_items)) creates drift. If you cache a derived value, document it, define the source of truth, and enforce updates consistently (often via application logic plus constraints).

Keys and Constraints: Speed Starts with Data Integrity

A fast database is usually a predictable database. Keys and constraints make your data predictable by preventing “impossible” states—missing relationships, duplicate identities, or values that don’t mean what the app thinks they mean. That cleanliness directly affects performance because the database can make better assumptions when planning queries.

Primary keys: every table needs a stable identifier

Every table should have a primary key (PK): a column (or small set of columns) that uniquely identifies a row and never changes. This isn’t just a theory-of-databases rule—it’s what lets you join tables efficiently, cache safely, and reference records without guesswork.

A stable PK also avoids expensive workarounds. If a table lacks a true identifier, applications start “identifying” rows by email, name, timestamp, or a bundle of columns—leading to wider indexes, slower joins, and edge cases when those values change.

Foreign keys: integrity that helps the optimizer

Foreign keys (FKs) enforce relationships: an orders.user_id must point to an existing users.id. Without FKs, invalid references creep in (orders for deleted users, comments for missing posts), and then every query has to defensively filter, left-join, and handle nulls.

With FKs in place, the query planner can often optimize joins more confidently because the relationship is explicit and guaranteed. You’re also less likely to accumulate orphan rows that bloat tables and indexes over time.

Constraints as guardrails for clean, fast data

Constraints aren’t bureaucracy—they’re guardrails:

- UNIQUE prevents duplicates that force the app to do extra lookups and cleanup. Example: one canonical

users.email. - NOT NULL avoids tri-state logic and surprise null-handling branches in queries.

- CHECK keeps values within a known set (e.g.,

status IN ('pending','paid','canceled')).

Cleaner data means simpler queries, fewer fallback conditions, and fewer “just in case” joins.

Common anti-patterns that slow you down

- No foreign keys: you’ll pay later with orphan cleanup jobs and complicated query logic.

- Duplicate “email” fields (e.g.,

users.emailandcustomers.email): you get conflicting identities and duplicate indexes. - Free-form status strings: typos like "Cancelled" vs "canceled" create hidden segments that break filters and reporting.

If you want speed early, make it hard to store bad data. The database will reward you with simpler plans, smaller indexes, and fewer performance surprises.

Normalization vs Denormalization: A Practical Balance

Build React and Go fast

Create a React app with a Go and PostgreSQL backend from one conversation.

Normalization is a simple idea: store each “fact” in one place so you don’t duplicate data all over your database. When the same value is copied into multiple tables or columns, updates get risky—one copy changes, another doesn’t, and your app starts showing conflicting answers.

Normalization (the default): one fact, one home

In practice, normalization means separating entities so updates are clean and predictable. For example, a product’s name and price belong in a products table, not repeated inside every order row. A category name belongs in categories, referenced by an ID.

This reduces:

- duplicated data (less storage, fewer inconsistencies)

- update errors (change once, reflected everywhere)

- confusing “which value is correct?” bugs

When over-normalization hurts

Normalization can be taken too far when you split data into many tiny tables that must be joined constantly for everyday screens. The database may still return correct results, but common reads become slower and more complex because every request needs multiple joins.

A typical early-stage symptom: a “simple” page (like an order history list) requires joining 6–10 tables, and performance varies depending on traffic and cache warmth.

A practical approach: normalize core facts, denormalize top reads

A sensible balance is:

- Normalize core facts and ownership (source of truth). Keep product attributes in

products, category names incategories, and relationships via foreign keys. - Denormalize carefully for the hottest reads—but only when you can explain the benefit and how it will stay correct.

Denormalization means intentionally duplicating a small piece of data to make a frequent query cheaper (fewer joins, faster lists). The key word is carefully: every duplicated field needs a plan for keeping it updated.

Example: products, categories, and order items

A normalized setup might look like:

products(id, name, price, category_id)categories(id, name)orders(id, customer_id, created_at)order_items(id, order_id, product_id, quantity, unit_price_at_purchase)

Notice the subtle win: order_items stores unit_price_at_purchase (a form of denormalization) because you need historical accuracy even if the product price changes later. That duplication is intentional and stable.

If your most common screen is “orders with item summaries,” you might also denormalize product_name into order_items to avoid joining products on every list—but only if you’re prepared to keep it in sync (or accept that it’s a snapshot at purchase time).

Index Strategy Follows Schema, Not the Other Way Around

Indexes are often treated like a magic “speed button,” but they only work well when the underlying table structure makes sense. If you’re still renaming columns, splitting tables, or changing how records relate to each other, your index set will churn too. Indexes work best when columns (and the way the app filters/sorts by them) are stable enough that you’re not rebuilding and rethinking them every week.

Start with the questions your app asks most

You don’t need perfect prediction, but you do need a short list of the queries that matter most:

- “Find a user by email.”

- “Show recent orders for a customer.”

- “List invoices by status, newest first.”

Those statements translate directly into which columns deserve an index. If you can’t say these out loud, it’s usually a schema clarity problem—not an indexing problem.

Composite indexes, explained plainly

A composite index covers more than one column. The order of columns matters because the database can use the index efficiently from left to right.

For example, if you often filter by customer_id and then sort by created_at, an index on (customer_id, created_at) is typically useful. The reverse (created_at, customer_id) may not help the same query nearly as much.

Don’t index everything

Every extra index has a cost:

- Slower writes: inserts/updates must update each index too.

- More storage: indexes can become a large portion of your database size.

- More complexity: extra indexes make maintenance and tuning harder.

A clean, consistent schema narrows the “right” indexes to a small set that matches real access patterns—without paying a constant write and storage tax.

Write Performance: The Hidden Cost of a Messy Schema

Add constraints the safe way

Model PKs, FKs, and checks up front to prevent slow queries later.

Slow apps aren’t always slowed down by reads. Many early performance issues show up during inserts and updates—user signups, checkout flows, background jobs—because a messy schema makes every write do extra work.

Why writes get expensive

A few schema choices quietly multiply the cost of every change:

- Wide rows: stuffing dozens (or hundreds) of columns into one table often means larger rows, more I/O, and more cache churn—even if most columns are rarely used.

- Too many indexes: indexes speed reads, but every insert/update must also update each index.

- Triggers and cascades: triggers can hide work (extra inserts/updates) behind a simple

INSERT. Cascading foreign keys can be correct and helpful, but they still add write-time work that grows with related data.

Read-heavy vs write-heavy: pick your pain deliberately

If your workload is read-heavy (feeds, search pages), you can afford more indexing and sometimes selective denormalization. If it’s write-heavy (event ingestion, telemetry, high-volume orders), prioritize a schema that keeps writes simple and predictable, then add read optimizations only where needed.

Common early-stage patterns that hurt writes

- Audit logs: great for compliance, but avoid logging huge snapshots on every update.

- Event tables: append-only tables scale well, but can become bloated if you store redundant payloads.

- Soft deletes: convenient, yet they increase index size and can slow updates and queries unless carefully planned.

Keep writes simple while preserving history

A practical approach:

- Store “current state” in one table, and history in a separate append-only table.

- Keep history rows narrow (only what you truly need: who/when/what changed).

- Add indexes to history based on real access patterns (usually

entity_id,created_at). - Avoid triggers for auditing at first; prefer explicit application writes so the cost is visible and testable.

Clean write paths give you headroom—and they make later query optimization far easier.

How ORMs and APIs Amplify Schema Decisions

ORMs make database work feel effortless: you define models, call methods, and data shows up. The catch is that an ORM can also hide expensive SQL until it hurts.

ORMs: convenience that can mask slow patterns

Two common traps:

- Inefficient joins: a seemingly simple

.include()or nested serializer can turn into wide joins, duplicate rows, or large sorts—especially if relationships aren’t clearly defined. - N+1 queries: you fetch 50 records, then the ORM quietly runs 50 more queries to load related data. It often works in development and collapses under real traffic.

A well-designed schema reduces the chance of these patterns emerging and makes them easier to detect when they do.

Clear relationships make ORM usage safer

When tables have explicit foreign keys, unique constraints, and not-null rules, the ORM can generate safer queries and your code can rely on consistent assumptions.

For example, enforcing that orders.user_id must exist (FK) and that users.email is unique prevents entire classes of edge cases that otherwise turn into application-level checks and extra query work.

APIs turn schema choices into product behavior

Your API design is downstream of your schema:

- Stable IDs (and consistent key types) make URLs, caching, and client-side state simpler.

- Pagination works best when you can order by an indexed, monotonic column (often

created_at+id). - Filtering becomes predictable when columns represent real attributes (not overloaded strings or JSON blobs) and constraints keep values clean.

Make it a workflow, not a rescue mission

Treat schema decisions as first-class engineering:

- Use migrations for every change, reviewed like code (/blog/migrations).

- Add lightweight “schema reviews” for new endpoints: what tables, what keys, what constraints, what query shape.

- In staging, log ORM queries and flag N+1 patterns before production (/blog/orm-performance-checks).

If you’re building quickly with a chat-driven development workflow (for example, generating a React app plus a Go/PostgreSQL backend in Koder.ai), it helps to make “schema review” part of the conversation early. You can iterate fast, but you still want constraints, keys, and a migration plan to be deliberate—especially before traffic arrives.

Early Warning Signs Your Schema Is the Bottleneck

Some performance problems aren’t “bad SQL” so much as the database fighting the shape of your data. If you see the same issues across many endpoints and reports, it’s often a schema signal, not a query-tuning opportunity.

Common symptoms to watch for

Slow filters are a classic tell. If simple conditions like “find orders by customer” or “filter by created date” are consistently sluggish, the problem may be missing relationships, mismatched types, or columns that can’t be indexed effectively.

Another red flag is exploding join counts: a query that should join 2–3 tables ends up chaining 6–10 tables just to answer a basic question (often due to over-normalized lookups, polymorphic patterns, or “everything in one table” designs).

Also watch for inconsistent values in columns that behave like enums—especially status fields (“active”, “ACTIVE”, “enabled”, “on”). Inconsistency forces defensive queries (LOWER(), COALESCE(), OR-chains) that stay slow no matter how much you tune.

Schema checklist (fast to verify)

- Missing indexes on foreign keys (joins become full scans as tables grow).

- Wrong data types (e.g., IDs stored as strings, dates stored as text, money as floats).

- EAV tables (Entity–Attribute–Value) used for core data: flexible at first, but filters/sorts turn into many joins and hard-to-index predicates.

Simple, tool-agnostic diagnostics

Start with reality checks: row counts per table, and cardinality for key columns (how many distinct values). If a “status” column has 4 expected values but you find 40, the schema is already leaking complexity.

Then look at query plans for your slow endpoints. If you repeatedly see sequential scans on join columns or large intermediate result sets, schema and indexing are the likely root.

Finally, enable and review slow query logs. When lots of different queries are slow in similar ways (same tables, same predicates), it’s usually a structural issue worth fixing at the model level.

Evolving the Schema Safely as You Grow

Deploy with hosting included

Deploy and host your app without setting up infrastructure first.

Early schema choices rarely survive first contact with real users. The goal isn’t to “get it perfect”—it’s to change it without breaking production, losing data, or freezing the team for a week.

A lightweight, repeatable change process

A practical workflow that scales from a one-person app to a larger team:

- Model: Write down the new shape (tables/columns, relationships, and what becomes source of truth). Include example records and edge cases.

- Migrate: Add new structures in a backward-compatible way (new columns/tables first; avoid removing or renaming immediately).

- Backfill: Populate new fields from existing data in batches. Track progress so you can resume.

- Validate: Add constraints only after data is clean (e.g., NOT NULL, foreign keys). Run checks that compare old vs new outputs.

Feature flags and dual writes (use sparingly)

Most schema changes don’t need complex rollout patterns. Prefer “expand-and-contract”: write code that can read both old and new, then switch writes once you’re confident.

Use feature flags or dual writes only when you truly need a gradual cutover (high traffic, long backfills, or multiple services). If you dual write, add monitoring to detect drift and define which side wins on conflict.

Rollbacks and migration testing that reflects reality

Safe rollbacks start with migrations that are reversible. Practice the “undo” path: dropping a new column is easy; recovering overwritten data isn’t.

Test migrations on realistic data volumes. A migration that finishes in 2 seconds on a laptop can lock tables for minutes in production. Use production-like row counts and indexes, and measure runtime.

This is where platform tooling can reduce risk: having reliable deployments plus snapshots/rollback (and the ability to export your code if needed) makes it safer to iterate on schema and app logic together. If you’re using Koder.ai, lean on snapshots and planning mode when you’re about to introduce migrations that might require careful sequencing.

Document decisions for the next person (including future you)

Keep a short schema log: what changed, why, and what trade-offs were accepted. Link it from /docs or your repo README. Include notes like “this column is intentionally denormalized” or “foreign key added after backfill on 2025-01-10” so future changes don’t repeat old mistakes.

When to Optimize Queries (and a Sensible Order of Operations)

Query optimization matters—but it pays off most when your schema isn’t fighting you. If tables are missing clear keys, relationships are inconsistent, or “one row per thing” is violated, you can spend hours tuning queries that will be rewritten next week.

A practical priority order

-

Fix schema blockers first. Start with anything that makes correct querying hard: missing primary keys, inconsistent foreign keys, columns that mix multiple meanings, duplicated source of truth, or types that don’t match reality (e.g., dates stored as strings).

-

Stabilize the access patterns. Once the data model reflects how the app behaves (and will likely behave for the next few sprints), tuning queries becomes durable.

-

Optimize the top queries—not all queries. Use logs/APM to identify the slowest and most frequent queries. A single endpoint hit 10,000 times a day usually beats a rare admin report.

The 80/20 of early query tuning

Most early wins come from a small set of moves:

- Add the right index for your most common filters and joins (and verify it’s actually used).

- Return fewer columns (avoid

SELECT *, especially on wide tables). - Avoid needless joins—sometimes a join exists only because the schema forces you to “discover” basic attributes.

Set expectations: it’s ongoing, but foundations come first

Performance work never ends, but the goal is to make it predictable. With a clean schema, each new feature adds incremental load; with a messy schema, each feature adds compound confusion.

This week’s checklist

- List the top 5 slowest and top 5 most frequent queries.

- For each, confirm: primary key present, joins are key-to-key, and types are correct.

- Add one index that matches the dominant filter/order.

- Replace

SELECT *in one hot path. - Re-measure and keep a simple “before/after” note for the next sprint.