Dec 25, 2025·8 min

Shipping integrations in India: CSV uploads vs courier APIs

Shipping integrations in India: decide what to automate vs keep manual by comparing CSV uploads to courier APIs, plus a practical checklist of tracking events.

Shipping integrations in India: decide what to automate vs keep manual by comparing CSV uploads to courier APIs, plus a practical checklist of tracking events.

When order volume is small, shipping updates can be handled with quick checks, a spreadsheet, and a couple of messages to the courier. As orders grow, small gaps add up: labels get created late, pickups get missed, and tracking stays stale.

The pattern is familiar: customers ask, “Where is my order?” Support asks ops. Ops checks a portal. Someone manually updates a status that should have updated on its own.

An integration simply means your system can send shipping data out (address, weight, COD, invoice value) and pull shipping data back in (AWB number, pickup confirmation, tracking scans, delivery results) in a reliable way. “Reliable” matters because it should work every day, not only when someone remembers to upload a file.

That’s why this comparison matters:

Most teams don’t want “more tech.” They want fewer delays, fewer manual edits, and tracking everyone can trust. Reduce follow-ups (from customers and internal teams), and you usually reduce refunds, reattempt costs, and support tickets too.

Most teams begin with a simple routine: book pickups, print labels, paste tracking IDs into a sheet, and reply when customers ask for updates. It works at low volume, but the cracks show quickly in India, especially when you juggle multiple couriers, COD, and inconsistent address quality.

The manual steps don’t look big on their own. Someone chooses a courier, creates the shipment, downloads labels, and makes sure the right package gets the right airway bill (AWB). Then someone else updates order status, shares tracking, and checks delivery proofs for COD.

The most common failure points look like:

NDR means Non-Delivery Report. It’s what happens when delivery fails (wrong address, customer unavailable, refusal, payment issue). NDR creates extra work because it forces decisions: call the customer, update the address, approve a reattempt, or mark it for return.

Ops feels the pressure first. Support gets the angry messages. Finance gets stuck on COD reconciliation. Customers feel the silence when statuses don’t change.

CSV upload is the default starting point for many shipping setups in India. You export a batch of paid orders from your store or ERP, format them into a courier or aggregator template, then upload the file in a dashboard to generate AWBs and labels.

What you get is simplicity. There’s usually no engineering work, and you can be live in a day. For low volume or predictable shipping (same pickup address, a small set of SKUs, few exceptions), a daily CSV can be “good enough” and easy to train.

Where it breaks down is everything after the upload. Most teams end up doing the same cleanup every day: fixing failed rows because a pin code or phone format doesn’t match the template, re-uploading corrected files, checking for accidental duplicates, and copy-pasting tracking numbers back into the storefront.

Then comes the messy part: chasing exceptions (address issues, payment problems, RTO risk) across emails, calls, and courier portals, and updating status in multiple places because the courier dashboard isn’t your system of record.

The hidden cost is time and inconsistency. Different couriers expect different columns and rules, so “one CSV” turns into multiple versions plus spreadsheet workarounds. And because updates aren’t real-time, support often learns about delays only when a customer complains.

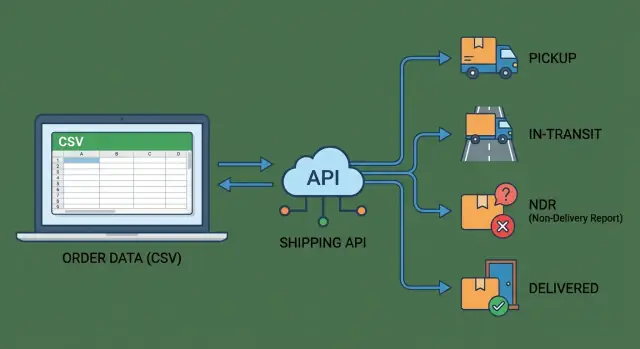

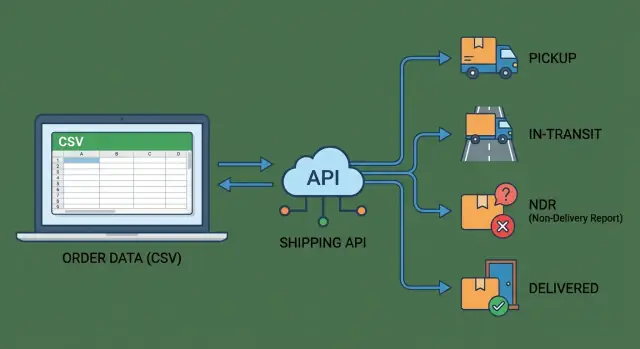

A full courier API setup means your system and the courier’s systems talk directly. Instead of uploading files, you send order and address details automatically, receive a label, and keep pulling tracking updates without anyone checking multiple portals. This is usually the point where shipping stops being a daily ops chore and starts behaving like dependable infrastructure.

Most teams start a courier API integration for three core actions: booking, labels, and tracking. Typical capabilities include creating a shipment and getting an AWB instantly, generating the shipping label and invoice data, requesting a pickup (where supported), and pulling tracking scans in near real time.

Once you have those basics, you can also handle exceptions more cleanly, like address issues and NDR status updates.

The payoff is straightforward: faster dispatch, fewer copy-paste mistakes, and clearer customer updates. If an order is paid at 2 pm, your system can auto-book the shipment, print the label, and send the tracking number within minutes, without waiting for a CSV export and re-upload.

API integrations aren’t “set and forget.” Plan time for setup, testing, and ongoing maintenance.

The usual sources of effort:

If you plan for these quirks early, the setup scales cleanly. If you don’t, you can end up with shipments booked but not picked up, or customers seeing confusing statuses because tracking events weren’t mapped correctly.

A simple rule works well: automate the tasks that happen many times a day and create the most rework when someone makes a small mistake.

In India, that usually means booking, labels, and tracking updates. One typo or one missed scan can trigger a chain of follow-ups.

Manual steps still have a place. Keep something manual when volume is low, when exceptions are frequent, or when courier processes aren’t consistent enough to trust automation.

A practical split by workflow:

A quick decision table before you build anything:

| Factor | When manual is fine | When automation pays off |

|---|---|---|

| Daily order volume | Under ~20/day | 50+/day or frequent spikes |

| Number of couriers | 1 courier | 2+ couriers or frequent switching |

| SLA pressure | 3-5 day delivery is acceptable | Same/next-day promises, high penalties |

| Team size | Dedicated ops person | Shared ops/support roles |

A simple checkpoint: if your team touches the same data twice (copy-paste from order to courier portal, then back into a sheet), that step is a strong automation candidate.

If you want fewer “where is my order?” messages, treat tracking like a timeline of events, not a single status. This matters in India, where the same shipment can bounce between hubs, reattempts, and returns.

Capture these stages so your team and customers see the same story:

For every event, store the same core fields: timestamp, location (city and hub if available), raw status text, normalized status, reason code, and the courier reference/AWB. Keeping both raw and normalized values makes audits and courier disputes easier.

Many shipping integrations fail for boring reasons: missing phone numbers, inconsistent weights, or no clear decision on which system “owns” the truth. Before you touch an API, lock down the minimum data you will always have for every order.

Start with a baseline that also works with CSV. If you can’t export these fields reliably, an API will only make errors happen faster:

Then define what you expect back from the courier, because these become your “handles” for everything else. At minimum, store shipment ID, AWB number, courier name or code, label reference, and pickup date or window.

One decision prevents weeks of confusion: pick your single source of truth for shipment status. If your team keeps checking the courier portal and overriding your system, customers will see one thing while support says another.

A simple mapping plan that keeps everyone aligned:

If you’re building this inside a tool like Koder.ai, treat these fields and mappings as first-class models early, so exports, tracking, and rollback don’t break when you add a second courier.

The safest upgrade path is a series of small switches, not one big cutover. Ops should keep shipping while the integration gets tighter.

Pick the couriers you’ll actually use, then confirm which actions you need now vs later: shipment booking, tracking, NDR handling, and returns (RTO). This matters because every courier names statuses differently and exposes different fields.

Before you automate booking or label creation, pull tracking events into your system and show them next to the order. This is low risk because it doesn’t change how parcels are created.

Make sure you can fetch events by AWB, and handle cases where the AWB is missing or wrong.

Create a small internal status model (pickup, in-transit, NDR, delivered), then map courier statuses into it. Also save every raw event payload exactly as received.

When a customer says “it shows delivered but I didn’t get it,” raw events help support answer quickly.

Automate the easy parts first: detect NDR, assign it to a queue, notify the customer, and set timers for reattempt windows.

Keep a manual override for address changes and special cases.

Once tracking is stable, add API booking, label generation, and pickup requests. Roll it out courier-by-courier, while keeping the CSV upload path as a fallback for a few weeks.

Test with real scenarios:

Most shipping tickets aren’t just “where is my order?” They’re mismatched expectations: your system says one thing, the courier says another, and the customer sees a third.

A common trap is assuming status text is uniform. The same milestone can show up as different phrases across zones, service types, or hubs. If you map by exact text instead of normalizing into your own small set of states, your dashboard and customer messages drift.

Mistakes that create delays and extra follow-ups:

A simple example: a customer calls saying the parcel was “returned.” Your system only shows “NDR.” If you stored the NDR reason and reattempt history, the agent could answer in one message instead of escalating to ops.

Before you declare success, test the integration the way ops and support will use it on a busy day. A courier status update that arrives late, or arrives without the right details, creates the same problem as no update at all.

Run a “one shipment, end to end” drill on at least 10 real orders across pincodes and payment types (prepaid and COD). Pick one order and time how long it takes to answer:

A quick checklist that catches most gaps:

If you’re building internal screens for this, keep the first version boring: one shipment search box, one clean timeline, and two buttons (manual note and override).

Tools like Koder.ai can help you prototype that ops dashboard quickly and export the source code when you’re ready to own it. If you want to explore it later, you can find it on koder.ai.

A mid-size D2C brand starts at about 20 orders a day, shipping mostly in one metro. They use two courier partners. The process is simple: export orders, upload a CSV twice a day, then copy-paste tracking numbers back into the store admin.

At 150 orders/day across three couriers, that routine starts to crack. Customers ask “where is my parcel?” and support has to check three portals.

The worst part is NDRs. A delivery attempt fails, someone from the courier calls, and the follow-up becomes a WhatsApp thread. Reattempts get missed, and a small delay turns into cancellations and refunds.

They move to a setup that syncs events automatically. Now every shipment update lands in one place, and the team works from a single queue instead of chat screenshots.

Day-to-day changes:

Not everything is automated. They still switch couriers manually for edge PIN codes or peak-season capacity issues. When a customer calls to correct an address, a human verifies it before any reattempt is triggered.

Decide what you need in the first 2-4 weeks. The biggest payoff usually comes from reliable tracking and fewer “where is my order?” tickets, not from building every feature on day one.

Pick a starting scope that matches your pain:

Before you write any code, lock the language you’ll use internally. Write your event checklist (pickup, in-transit, NDR, delivered) and map each courier status to one of your own statuses. If you skip this, you’ll end up with five “in transit” variants and unclear rules for when to notify a customer, open an NDR task, or mark an order complete.

A safe rollout looks like: one courier, one lane (or one warehouse), then expand.

Run your new flow in parallel with your CSV upload process for a short time so ops can compare AWBs, labels, and tracking updates. Keep a simple fallback: if the API call fails, create a task for manual booking instead of blocking dispatch.

If you want to move quickly, prototype the courier API integration with Koder.ai: define the event storage table, the status-mapping rules, and a small ops dashboard (search by order or AWB, last event, next action). When it behaves the way your team expects, export the source code and harden it with retries, logging, and access controls.

A good first version isn’t “complete.” It’s one courier working end-to-end, with clean events, clear ownership for NDR, and a daily view that tells ops what needs attention right now.

CSV uploads are fine when volume is low (for example, under ~20 orders/day), you use one courier, and exceptions are rare. They’re also a good fallback when an API is down. The risk is that every missed step (late upload, wrong template, copy‑paste errors) turns into support follow‑ups and delayed dispatch.

A courier API usually pays off when you’re doing 50+ orders/day, using 2+ couriers, or seeing frequent NDR/reattempts. You get faster booking and labels, near real‑time tracking, and fewer manual updates. The main cost is setup and ongoing maintenance for courier quirks and status mapping.

Start with:

If these fields are inconsistent in exports, an API will fail faster and more often than CSV.

Store at least:

These become your “handles” to fetch tracking, reconcile issues, and answer support quickly.

Track a timeline, not a single status:

For every event, keep timestamp, location, raw status text, normalized status, reason code, and AWB.

Treat NDR as a workflow:

Keep a manual override for address changes and risky COD reattempts so automation doesn’t create bad repeats.

Define a small set of internal states (Created, Picked Up, In Transit, Out for Delivery, Delivered, NDR, Returned). Map every courier event into one of these, but also store the raw courier status text separately. Don’t map by exact text only—couriers vary by zone, service type, and hub wording.

Do it in phases:

Keep CSV as a fallback for a few weeks so dispatch never blocks.

Plan for failures by default:

This prevents silent tracking gaps that create support tickets.

Use safeguards in both process and data:

Most “lost” shipments start as an ID mix‑up, not a courier problem.