Jul 10, 2025·8 min

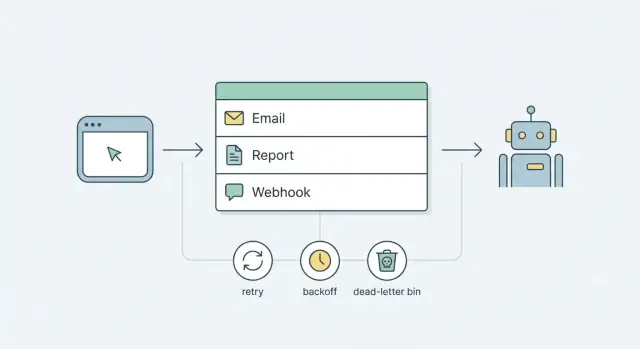

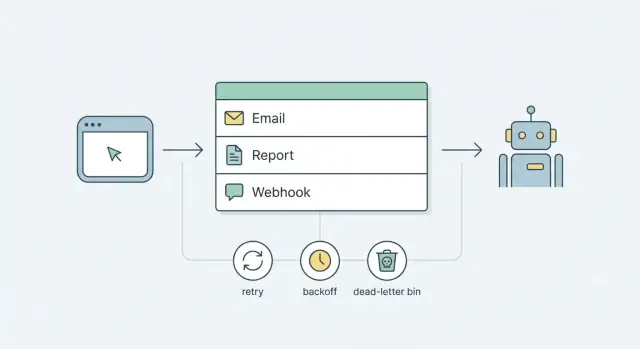

Simple background job queue patterns for emails and webhooks

Learn simple background job queue patterns to send emails, run reports, and deliver webhooks with retries, backoff, and dead-letter handling, without heavy tools.

Learn simple background job queue patterns to send emails, run reports, and deliver webhooks with retries, backoff, and dead-letter handling, without heavy tools.

Any work that can take longer than a second or two shouldn't run inside a user request. Sending emails, generating reports, and delivering webhooks all depend on networks, third-party services, or slow queries. Sometimes they pause, fail, or just take longer than you expect.

If you do that work while the user waits, people notice immediately. Pages hang, "Save" buttons spin, and requests time out. Retries can also happen in the wrong place. A user refreshes, your load balancer retries, or your frontend resubmits, and you end up with duplicate emails, duplicate webhook calls, or two report runs competing with each other.

Background jobs fix this by keeping requests small and predictable: accept the action, record a job to do later, respond quickly. The job runs outside the request, with rules you control.

The hard part is reliability. Once work moves out of the request path, you still have to answer questions like:

Many teams respond by adding "heavy infrastructure": a message broker, separate worker fleets, dashboards, alerting, and playbooks. Those tools are useful when you truly need them, but they also add new moving parts and new failure modes.

A better starting goal is simpler: reliable jobs using parts you already have. For most products, that means a database-backed queue plus a small worker process. Add a clear retry and backoff strategy, and a dead-letter pattern for jobs that keep failing. You get predictable behavior without committing to a complex platform on day one.

Even if you're building quickly with a chat-driven tool like Koder.ai, this separation still matters. Users should get a fast response now, and your system should finish slow, failure-prone work safely in the background.

A queue is a waiting line for work. Instead of doing slow or unreliable tasks during a user request (send an email, build a report, call a webhook), you put a small record in a queue and return quickly. Later, a separate process picks up that record and does the work.

A few words you'll see often:

The simplest flow looks like this:

Enqueue: your app saves a job record (type, payload, run time).

Claim: a worker finds the next available job and "locks" it so only one worker runs it.

Run: the worker performs the task (send, generate, deliver).

Finish: mark it done, or record a failure and set the next run time.

If your job volume is modest and you already have a database, a database-backed queue is often enough. It's easy to understand, easy to debug, and fits common needs like email job processing and webhook delivery reliability.

Streaming platforms start to make sense when you need very high throughput, lots of independent consumers, or the ability to replay huge event histories across many systems. If you're running dozens of services with millions of events per hour, tools like Kafka can help. Until then, a database table plus a worker loop covers a lot of real-world queues.

A database queue only stays sane if each job record answers three questions quickly: what to do, when to try next, and what happened last time. Get that right and operations become boring (which is the goal).

Store the smallest input needed to do the work, not the entire rendered output. Good payloads are IDs and a few parameters, like { "user_id": 42, "template": "welcome" }.

Avoid storing big blobs (full HTML emails, large report data, huge webhook bodies). It makes your database grow faster and makes debugging harder. If the job needs a large document, store a reference instead: report_id, export_id, or a file key. The worker can fetch the full data when it runs.

At minimum, make room for:

job_type selects the handler (send_email, generate_report, deliver_webhook). payload holds small inputs like IDs and options.queued, running, succeeded, failed, dead).attempt_count and max_attempts so you can stop retrying when it clearly won't work.created_at and next_run_at (when it becomes eligible). Add started_at and finished_at if you want better visibility into slow jobs.idempotency_key to prevent double effects, and last_error so you can see why it failed without digging through a pile of logs.Idempotency sounds fancy, but the idea is simple: if the same job runs twice, the second run should detect that and do nothing dangerous. For example, a webhook delivery job can use an idempotency key like webhook:order:123:event:paid so you don't deliver the same event twice if a retry overlaps with a timeout.

Also capture a few basic numbers early. You don't need a big dashboard to start, just queries that tell you: how many jobs are queued, how many are failing, and the age of the oldest queued job.

If you already have a database, you can start a background queue without adding new infrastructure. Jobs are rows, and a worker is a process that keeps picking due rows and doing the work.

Keep the table small and boring. You want enough fields to run, retry, and debug jobs later.

CREATE TABLE jobs (

id bigserial PRIMARY KEY,

job_type text NOT NULL,

payload jsonb NOT NULL,

status text NOT NULL DEFAULT 'queued', -- queued, running, done, failed

attempts int NOT NULL DEFAULT 0,

next_run_at timestamptz NOT NULL DEFAULT now(),

locked_at timestamptz,

locked_by text,

last_error text,

created_at timestamptz NOT NULL DEFAULT now(),

updated_at timestamptz NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

CREATE INDEX jobs_due_idx ON jobs (status, next_run_at);

If you're building on Postgres (common with Go backends), jsonb is a practical way to store job data like { "user_id":123,"template":"welcome" }.

When a user action should trigger a job (send an email, fire a webhook), write the job row in the same database transaction as the main change when possible. That prevents "user created but job missing" if a crash happens right after the main write.

Example: when a user signs up, insert the user row and a send_welcome_email job in one transaction.

A worker repeats the same cycle: find one due job, claim it so no one else can take it, process it, then mark it done or schedule a retry.

In practice, that means:

status='queued' and next_run_at <= now().SELECT ... FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED is a common approach).status='running', locked_at=now(), locked_by='worker-1'.done/succeeded), or record last_error and schedule the next attempt.Multiple workers can run at the same time. The claim step is what prevents double-picking.

On shutdown, stop taking new jobs, finish the current one, then exit. If a process dies mid-job, use a simple rule: treat jobs stuck in running past a timeout as eligible to be re-queued by a periodic "reaper" task.

If you're building in Koder.ai, this database-queue pattern is a solid default for emails, reports, and webhooks before you add specialized queue services.

Retries are how a queue stays calm when the real world is messy. Without clear rules, retries turn into a noisy loop that spams users, hammers APIs, and hides the real bug.

Start by deciding what should retry and what should fail fast.

Retry temporary problems: network timeouts, 502/503 errors, rate limits, or a brief database connection blip.

Fail fast when the job won't succeed: a missing email address, a 400 response from a webhook because the payload is invalid, or a report request for a deleted account.

Backoff is the pause between attempts. Linear backoff (5s, 10s, 15s) is simple, but it can still create waves of traffic. Exponential backoff (5s, 10s, 20s, 40s) spreads load better and is usually safer for webhooks and third-party providers. Add jitter (a small random extra delay) so a thousand jobs don't retry at the exact same second after an outage.

Rules that tend to behave well in production:

Max attempts is about limiting damage. For many teams, 5 to 8 attempts is enough. After that, stop retrying and park the job for review (a dead-letter flow) instead of looping forever.

Timeouts prevent "zombie" jobs. Emails might time out at 10 to 20 seconds per attempt. Webhooks often need a shorter limit, like 5 to 10 seconds, because the receiver may be down and you want to move on. Report generation might allow minutes, but it should still have a hard cutoff.

If you're building this in Koder.ai, treat should_retry, next_run_at, and an idempotency key as first-class fields. Those small details keep the system quiet when something goes wrong.

A dead-letter state is where jobs go when retries are no longer safe or useful. It turns silent failure into something you can see, search, and act on.

Save enough to understand what happened and to replay the job without guessing, but be careful about secrets.

Keep:

If the payload includes tokens or personal data, redact or encrypt before storing.

When a job hits dead-letter, make a quick decision: retry, fix, or ignore.

Retry is for external outages and timeouts. Fix is for bad data (missing email, wrong webhook URL) or a bug in your code. Ignore should be rare, but it can be valid when the job is no longer relevant (for example, the customer deleted their account). If you ignore, record a reason so it doesn't look like the job vanished.

Manual requeue is safest when it creates a new job and keeps the old one immutable. Mark the dead-letter job with who requeued it, when, and why, then enqueue a fresh copy with a new ID.

For alerting, watch for signals that usually mean real pain: dead-letter count rising quickly, the same error repeating across many jobs, and old queued jobs that aren't being claimed.

If you're using Koder.ai, snapshots and rollback can help when a bad release suddenly spikes failures, because you can back out quickly while you investigate.

Finally, add safety valves for vendor outages. Rate-limit sends per provider, and use a circuit breaker: if a webhook endpoint is failing hard, pause new attempts for a short window so you don't flood their servers (and yours).

A queue works best when each job type has clear rules: what counts as success, what should be retried, and what must never happen twice.

Emails. Most email failures are temporary: provider timeouts, rate limits, or short outages. Treat those as retryable, with backoff. The bigger risk is duplicate sends, so make email jobs idempotent. Store a stable dedupe key such as user_id + template + event_id and refuse to send if that key is already marked as sent.

It's also worth storing the template name and version (or a hash of the rendered subject/body). If you ever need to re-run jobs, you can choose whether to resend the exact same content or regenerate from the latest template. If the provider returns a message ID, save it so support can trace what happened.

Reports. Reports fail differently. They can run for minutes, hit pagination limits, or run out of memory if you do everything in one go. Split work into smaller pieces. A common pattern is: one "report request" job creates many "page" (or "chunk") jobs, each processing a slice of data.

Store results for later download instead of keeping the user waiting. That can be a database table keyed by report_run_id, or a file reference plus metadata (status, row count, created_at). Add progress fields so the UI can show "processing" vs "ready" without guessing.

Webhooks. Webhooks are about delivery reliability, not speed. Sign every request (for example, HMAC with a shared secret) and include a timestamp to prevent replay. Retry only when the receiver might succeed later.

A simple ruleset:

Ordering and priority. Most jobs don't need strict ordering. When order matters, it usually matters per key (per user, per invoice, per webhook endpoint). Add a group_key and only run one in-flight job per key.

For priority, separate urgent work from slow work. A large report backlog shouldn't delay password reset emails.

Example: after a purchase, you enqueue (1) an order confirmation email, (2) a partner webhook, and (3) a report update job. The email can retry quickly, the webhook retries longer with backoff, and the report runs later at low priority.

A user signs up for your app. Three things should happen, but none of them should slow down the signup page: send a welcome email, notify your CRM with a webhook, and include the user in a nightly activity report.

Right after you create the user record, write three job rows to your database queue. Each row has a type, a payload (like user_id), a status, an attempt count, and a next_run_at timestamp.

A typical lifecycle looks like this:

queued: created and waiting for a workerrunning: a worker has claimed itsucceeded: done, no more workfailed: failed, scheduled for later or out of retriesdead: failed too many times and needs a human lookThe welcome email job includes an idempotency key like welcome_email:user:123. Before sending, the worker checks a table of completed idempotency keys (or enforces a unique constraint). If the job runs twice because of a crash, the second run sees the key and skips sending. No double welcome emails.

Now the CRM webhook endpoint is down. The webhook job fails with a timeout. Your worker schedules a retry using backoff (for example: 1 minute, 5 minutes, 30 minutes, 2 hours) plus a little jitter so many jobs don't retry at the same second.

After the max attempts, the job becomes dead. The user still signed up, got the welcome email, and the nightly report job can run as normal. Only the CRM notification is stuck, and it's visible.

The next morning, support (or whoever is on call) can handle it without digging through logs for hours:

webhook.crm).If you build apps on a platform like Koder.ai, the same pattern applies: keep the user flow fast, push side effects into jobs, and make failures easy to inspect and re-run.

The fastest way to break a queue is to treat it as optional. Teams often start with "just send the email in the request this one time" because it feels simpler. Then it spreads: password resets, receipts, webhooks, report exports. Soon the app feels slow, timeouts rise, and any third-party hiccup becomes your outage.

Another common trap is skipping idempotency. If a job can run twice, it must not create two results. Without idempotency, retries turn into duplicate emails, repeated webhook events, or worse.

A third issue is visibility. If you only learn about failures from support tickets, the queue is already harming users. Even a basic internal view that shows job counts by status plus searchable last_error saves time.

A few issues show up early, even in simple queues:

Backoff prevents self-made outages. Even a basic schedule like 1 minute, 5 minutes, 30 minutes, 2 hours makes failure safer. Also set a max attempts limit so a broken job stops and becomes visible.

If you're building on a platform like Koder.ai, it helps to ship these basics alongside the feature itself, not weeks later as a cleanup project.

Before you add more tooling, make sure the basics are solid. A database-backed queue works well when each job is easy to claim, easy to retry, and easy to inspect.

A quick reliability checklist:

Next, pick your first three job types and write down their rules. For example: password reset email (fast retries, short max), nightly report (few retries, longer timeouts), webhook delivery (more retries, longer backoff, stop on permanent 4xx).

If you're unsure when a database queue stops being enough, watch for signals like row-level contention from many workers, strict ordering needs across many job types, large fan-out (one event triggers thousands of jobs), or cross-service consumption where different teams own different workers.

If you want a fast prototype, you can sketch the flow in Koder.ai (koder.ai) using planning mode, generate the jobs table and worker loop, and iterate with snapshots and rollback before deploying.

If a task can take more than a second or two, or depends on a network call (email provider, webhook endpoint, slow query), move it to a background job.

Keep the user request focused on validating input, writing the main data change, enqueueing a job, and returning a fast response.

Start with a database-backed queue when:

Add a broker/streaming tool later when you need very high throughput, many independent consumers, or cross-service event replay.

Track the basics that answer: what to do, when to try next, and what happened last time.

A practical minimum:

Store inputs, not big outputs.

Good payloads:

user_id, template, report_id)Avoid:

The key is an atomic “claim” step so two workers can’t take the same job.

Common approach in Postgres:

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED)running and set locked_at/locked_byThen your workers can scale horizontally without double-processing the same row.

Assume jobs will run twice sometimes (crashes, timeouts, retries). Make the side effect safe.

Simple patterns:

idempotency_key like welcome_email:user:123This is especially important for emails and webhooks to prevent duplicates.

Use a clear default policy and keep it boring:

Fail fast on permanent errors (like missing email address, invalid payload, most 4xx webhook responses).

Dead-letter means “stop retrying and make it visible.” Use it when:

max_attemptsStore enough context to act:

Handle “stuck running” jobs with two rules:

running jobs older than a threshold and re-queues them (or marks them failed)This lets the system recover from worker crashes without manual cleanup.

Use separation so slow work can’t block urgent work:

If ordering matters, it’s usually “per key” (per user, per webhook endpoint). Add a group_key and ensure only one in-flight job per key to preserve local ordering without forcing global ordering.

job_type, payloadstatus (queued, running, succeeded, failed, dead)attempts, max_attemptsnext_run_at, plus created_atlocked_at, locked_bylast_erroridempotency_key (or another dedupe mechanism)If the job needs big data, store a reference (like report_run_id or a file key) and fetch the real content when the worker runs.

last_error and last status code (for webhooks)When you replay, prefer creating a new job and keeping the dead one immutable.