Nov 15, 2025·8 min

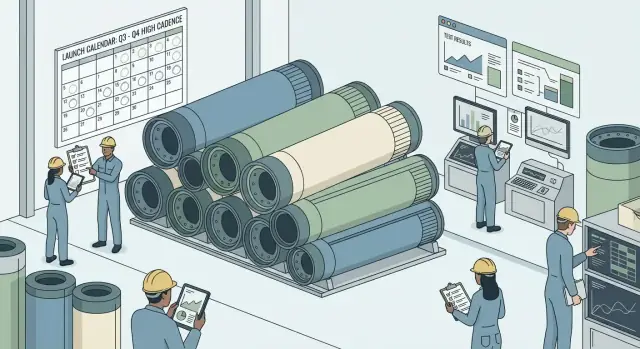

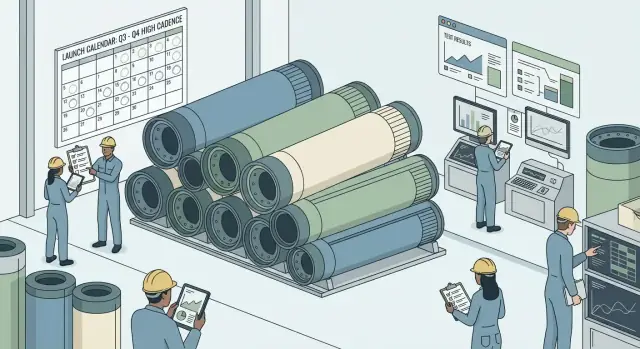

SpaceX’s Software-Like Rocket Strategy: Cadence as a Moat

A plain-English look at how SpaceX built a fast feedback loop with vertical integration, making rockets evolve like software—and how launch cadence becomes a moat.

A plain-English look at how SpaceX built a fast feedback loop with vertical integration, making rockets evolve like software—and how launch cadence becomes a moat.

SpaceX’s defining bet isn’t just “make rockets reusable.” It’s that a rocket program can be run with a software-like mindset: ship a working version, learn from real-world use quickly, and fold those lessons into the next build—again and again.

That framing matters because it shifts the goal from building a single “perfect” vehicle to building an improvement engine. You still need aerospace-grade engineering and safety. But you also treat every launch, landing, test firing, and refurbishment as data that tightens designs and operations.

Cadence—how often you launch—turns iteration from a slogan into a compounding advantage.

When flights are rare, feedback is slow. Problems take longer to reproduce, teams lose context, suppliers change parts, and improvements arrive in big, risky batches.

When flights are frequent, feedback loops shorten. You observe performance in varied conditions, validate fixes faster, and build institutional memory. Over time, high cadence can lower cost (through steadier production and reuse) and raise reliability (through repeated exposure to real operating conditions).

This article focuses on mechanisms, not hype. We won’t lean on exact numbers or sweeping claims. Instead, we’ll look at the practical system: how manufacturing, integration, operations, and learning speed reinforce each other.

Iteration: A cycle of building, testing, learning, and updating—often in smaller, faster steps rather than giant redesigns.

Integration (vertical integration): Owning more of the “stack,” from design and manufacturing to software and operations, so decisions and changes don’t wait on long external handoffs.

Moat: A durable advantage that’s hard for competitors to copy. Here, the moat isn’t a single invention; it’s a flywheel where cadence accelerates learning, learning improves vehicles and operations, and those improvements make higher cadence easier.

Vertical integration, in plain terms, means making more of the key parts yourself instead of buying them from a long chain of suppliers. Rather than acting mainly as a “systems integrator” that assembles other companies’ components, you own more of the design and manufacturing end-to-end.

Old-school aerospace often leaned heavily on contractors for a few practical reasons:

When more of the stack sits under one roof (or one set of internal teams), coordination gets simpler. There are fewer “interfaces” between companies, fewer contractual boundaries, and fewer rounds of negotiation every time a design changes.

That matters because iteration in hardware depends on quick loops:

Vertical integration isn’t automatically better. You take on higher fixed costs (facilities, equipment, staffing) and you need broad in-house expertise across many disciplines. If your launch rate or production volume drops, you still carry those costs.

It can also create new internal bottlenecks: when you own everything, you can’t outsource accountability—you have to build the capability yourself, and that requires sustained management attention.

SpaceX’s iteration speed isn’t just a design story—it’s a factory story. Manufacturing speed affects test speed, which affects design speed. If it takes weeks to build the next unit, the team waits weeks to learn whether a change helped. If it takes days, learning becomes routine.

A factory that can consistently produce parts on a tight rhythm turns experiments into a pipeline instead of special events. That matters because rockets don’t “debug” cheaply in the field; the closest equivalent is building, testing, and flying real hardware. When production is slow, every test is precious and schedules become fragile. When production is fast, teams can take more shots on goal while still controlling risk.

Standardization is the quiet accelerator: common interfaces, repeatable parts, and shared processes mean a change in one area doesn’t force redesign everywhere else. When connectors, mounting points, software hooks, and test procedures are consistent, teams spend less time “making it fit” and more time improving performance.

Owning tooling—jigs, fixtures, test stands, and measurement systems—lets teams update the production system as quickly as they update the product. Automation helps twice: it speeds up repetitive work and makes quality more measurable, so teams can trust results and move on.

DFM means designing parts that are easier to build the same way every time: fewer unique components, simpler assemblies, and tolerances that match real shop capabilities. The payoff isn’t just cost reduction—it’s shorter change cycles, because the “next version” doesn’t require reinventing how to build it.

SpaceX’s iteration loop looks less like “design once, certify, then fly” and more like a repeated cycle of build → test → learn → change. The power isn’t any single breakthrough—it’s the compounding effect of many small improvements made quickly, before assumptions harden into program-wide commitments.

The key is treating hardware as something you can touch early. A part that passes a paper review can still crack, vibrate, leak, or behave strangely when cold-soaked, heated, or stressed in ways spreadsheets can’t fully capture. Frequent tests surface these reality checks sooner, when fixes are cheaper and don’t ripple across an entire vehicle.

That’s why SpaceX emphasizes instrumented testing—static fires, tanks, valves, engines, stage separation events—where the goal is to observe what actually happens, not what should happen.

Paper reviews are valuable for catching obvious issues and aligning teams. But they tend to reward confidence and completeness, while tests reward truth. Running hardware exposes:

Iteration doesn’t mean being careless. It means designing experiments so that failures are survivable: protect people, limit blast radius, capture telemetry, and turn the outcome into clear engineering action. A failure in a test article can be an information-rich event; the same failure during an operational mission is reputational and customer-impacting.

A useful distinction is intent:

Keeping that boundary clear lets speed and discipline coexist.

SpaceX is often described as treating rockets like software: build, test, learn, ship an improved “version.” The comparison isn’t perfect, but it explains a real shift in how modern launch systems get better over time.

Software teams can push updates daily because mistakes are reversible and rollback is cheap. Rockets are physical machines operating at extreme margins; failures are expensive and sometimes catastrophic. That means iteration has to pass through manufacturing reality and safety gates: parts must be built, assembled, inspected, tested, and certified.

What makes rocket development feel more “software-like” is compressing that physical cycle—turning months of uncertainty into weeks of measured progress.

Iteration speeds up when components are designed to be swapped, refurbished, and tested repeatedly. Reusability isn’t just about saving hardware; it creates more opportunities to examine flown parts, validate assumptions, and feed improvements back into the next build.

A few enablers make that loop tighter:

Software teams learn from logs and monitoring. SpaceX learns from dense telemetry: sensors, high-rate data streams, and automated analysis that turn each test firing and flight into a dataset. The faster data becomes insight—and insight becomes a design change—the more iteration compounds.

Rockets still obey constraints software doesn’t:

So rockets can’t iterate like apps. But with modular design, heavy instrumentation, and disciplined testing, they can iterate enough to capture a key benefit of software: steady improvement driven by tight feedback loops.

Launch cadence is easy to treat as a vanity metric—until you see the second-order effects it creates. When a team flies often, every launch generates fresh data on hardware performance, weather decisions, range coordination, countdown timing, and recovery operations. That volume of “real-world reps” accelerates learning in a way simulations and occasional missions can’t fully match.

Each additional launch produces a broader sample of outcomes: minor anomalies, off-nominal sensor readings, turnaround surprises, and ground-system quirks. Over time, patterns emerge.

That matters for reliability, but also for confidence. A vehicle that has flown frequently under varied conditions becomes easier to trust—not because anyone is hand-waving risk away, but because there’s a thicker record of what actually happens.

High cadence doesn’t just improve rockets. It improves people and process.

Ground crews refine procedures through repetition. Training becomes clearer because it’s anchored in recent events, not legacy documentation. Tooling, checklists, and handoffs get tightened. Even the “boring” parts—pad flow, propellant loading, comms protocols—benefit from being exercised regularly.

A launch program carries large fixed costs: facilities, specialized equipment, engineering support, safety systems, and management overhead. Flying more often can push the average cost per launch down by spreading those fixed expenses across a larger number of missions.

At the same time, a predictable rhythm reduces thrash. Teams plan staffing, maintenance windows, and inventory with fewer emergencies and less idle time.

Cadence also changes the supply side. Regular demand tends to improve supplier negotiations, shorten lead times, and reduce expediting fees. Internally, stable schedules make it easier to stage parts, allocate test assets, and avoid last-minute reshuffles.

Put together, cadence becomes a flywheel: more launches create more learning, which improves reliability and efficiency, which enables more launches.

A high launch cadence isn’t just “more launches.” It’s a system advantage that compounds. Each flight generates data, stress-tests operations, and forces teams to solve real problems under real constraints. When you can do that repeatedly—without long resets—you climb the learning curve faster than competitors.

Cadence creates a three-part flywheel:

A rival can copy a design feature, but matching cadence requires an end-to-end machine: manufacturing rate, supply chain responsiveness, trained crews, ground infrastructure, and the discipline to run repeatable processes. If any link is slow, cadence stalls—and the compounding advantage disappears.

A big backlog can coexist with low tempo if vehicles, pads, or operations are constrained. Cadence is about sustained execution, not marketing demand.

If you want to judge whether cadence is turning into a durable advantage, track:

Those metrics reveal whether the system is scaling—or merely sprinting occasionally.

Reusing a rocket sounds like an automatic cost win: fly it again, pay less. In practice, reusability only lowers marginal cost if the time and labor between flights are kept under control. A booster that needs weeks of careful rework becomes a museum piece, not a high-velocity asset.

The key question isn’t “Can we land it?” but “How quickly can we certify it for the next mission?” Fast refurbishment turns reuse into a schedule advantage: fewer new stages to build, fewer long-lead parts to wait on, and more opportunities to launch.

That speed depends on designing for serviceability (easy access, modular swaps) and on learning what not to touch. Every avoided teardown is a compounding savings in labor, tooling, and calendar time.

Quick turnaround is less about heroics and more about standard operating procedures (SOPs). Clear checklists, repeatable inspections, and “known good” workflows reduce variation—the hidden enemy of fast reuse.

SOPs also make performance measurable: turnaround hours, defect rates, and recurring failure modes. When teams can compare flights apples-to-apples, iteration becomes focused rather than chaotic.

Reuse is limited by operational realities:

Handled well, reuse increases launch cadence, and higher cadence improves reuse. More flights generate more data, which tightens procedures, improves designs, and reduces per-flight uncertainty—turning reusability into an enabler of the cadence flywheel, not a shortcut to cheap launches.

SpaceX’s push to build more of its own hardware isn’t just about saving money—it’s about protecting the schedule. When a mission depends on a single late valve, chip, or casting, the rocket program inherits the supplier’s calendar. By bringing key components in-house, you cut the number of external handoffs and reduce the chance that an upstream delay turns into a missed launch window.

Internal supply chains can be aligned to the same priorities as the launch team: faster change approvals, tighter coordination on engineering updates, and fewer surprises about lead times. If a design tweak is needed after a test, an integrated team can iterate without renegotiating contracts or waiting for a vendor’s next production slot.

Making more parts yourself still leaves real constraints:

As flight volume rises, make-vs-buy decisions often change. Early on, buying can look faster; later, higher throughput can justify dedicated internal lines, tooling, and QA resources. The goal isn’t “build everything,” but “control what controls your schedule.”

Vertical integration can create single points of failure: if one internal cell falls behind, there’s no second supplier to pick up the slack. That raises the bar for quality control, redundancy in critical processes, and clear acceptance standards—so speed doesn’t quietly turn into rework and scrapped parts.

Speed in aerospace isn’t just a timeline—it’s an organizational design choice. SpaceX’s pace depends on clear ownership, fast decisions, and a culture that treats every test as a data-gathering opportunity rather than a courtroom.

A common failure mode in large engineering programs is “shared responsibility,” where everyone can comment but no one can decide. SpaceX-style execution emphasizes single-threaded ownership: a specific person or small team is accountable for a subsystem end to end—requirements, design tradeoffs, testing, and fixes.

That structure reduces handoffs and ambiguity. It also makes prioritization easier: when a decision has a name on it, the organization can move quickly without waiting for broad consensus.

Rapid iteration only works if you can learn faster than you break things. That requires:

The point isn’t paperwork for its own sake. It’s to make learning cumulative—so fixes stick, and new engineers can build on what the last team discovered.

“Move fast” in rocketry still needs guardrails. Effective gates are narrow and high-impact: they verify critical hazards, interfaces, and mission assurance items, while letting lower-risk improvements flow through.

Instead of turning every change into a months-long approval cycle, teams define what triggers deeper review (e.g., propulsion changes, flight software safety logic, structural margins). Everything else ships through a lighter path.

If the only rewarded outcome is “no mistakes,” people hide issues and avoid ambitious tests. A healthier system celebrates well-designed experiments, transparent reporting, and rapid corrective action—so the organization gets smarter every cycle, not just safer on paper.

Rocket iteration doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Even with a fast-moving engineering culture, launch cadence is bounded by licensing, range schedules, and safety rules that don’t compress just because a team wants shorter cycles.

In the U.S., each launch requires regulatory approvals and a clear safety case. Environmental reviews, flight safety analyses, and public risk thresholds create real lead times. Even if a vehicle and payload are ready, the range (tracking, airspace and maritime closures, coordination with other users) can be the gating factor. Cadence, in practice, becomes a negotiation between factory output, operational readiness, and the external calendar.

Uncrewed test flights can tolerate more uncertainty and learn faster from anomalies—within safety limits. Crewed missions raise the bar: redundancy, abort capability, and formal verification reduce the room for improvisation. National security missions add another constraint layer: stricter assurance, documentation, and often less tolerance for iterative changes close to flight. The playbook shifts from “try, learn, ship” toward “change control, prove, then fly.”

As a provider becomes the default choice, expectations move from “impressive for new hardware” to “airline-like predictability.” That changes incentives: the same fast feedback loops remain valuable, but more learning must happen on the ground (process audits, component screening, qualification testing) rather than by accepting higher flight risk.

High-profile mishaps create public scrutiny and regulatory pressure, which can slow iteration. But disciplined internal reporting—treating near-misses as data, not blame—lets learning compound without waiting for a public failure to force change.

SpaceX’s headline achievements are aerospace-specific, but the operating ideas underneath translate well—especially for companies that build physical products or run complex operations.

The most portable lessons are about learning speed:

You don’t need to build engines to benefit from these. A retail chain can apply them to store layouts, a healthcare group to patient flow, a manufacturer to yield and rework.

Start with process, not heroics:

If you want a lightweight way to apply the same “ship → learn → improve” rhythm in software delivery, platforms like Koder.ai push the feedback loop closer to real usage by letting teams build and iterate web, backend, and mobile apps via chat—while still keeping practical controls like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback.

Owning more of the stack can backfire when:

Track a small set of metrics consistently:

Borrow the playbook, not the product: build a system where learning compounds.

It means running rocket development like an iterative product loop: build → test → learn → change. Instead of waiting for one “perfect” design, teams ship workable versions, gather real operating data (tests and flights), and roll improvements into the next build.

In rockets, the loop is slower and higher-stakes than software, but the principle is the same: shorten feedback cycles so learning compounds.

Cadence turns learning into a compounding advantage. With frequent flights, you get more real-world data, validate fixes faster, and keep teams and suppliers in a steady rhythm.

Low cadence stretches feedback over months or years, making problems harder to reproduce, fixes riskier, and institutional knowledge easier to lose.

Vertical integration reduces external handoffs. When the same organization controls design, manufacturing, testing, and operations, changes don’t have to wait on vendor schedules, contract renegotiations, or cross-company interface work.

Practically, it enables:

The main trade-offs are fixed cost and internal bottlenecks. Owning more of the stack means paying for facilities, tooling, staffing, and quality systems even when volume dips.

It can also concentrate risk: if an internal production cell slips, there may be no second supplier to backstop schedule. The payoff only works if management can keep quality, throughput, and prioritization disciplined.

A fast factory makes testing routine instead of exceptional. If building the “next unit” takes weeks, learning waits; if it takes days, teams can run more experiments, isolate variables, and confirm improvements sooner.

Manufacturing speed also stabilizes operations: predictable output supports steadier launch planning, inventory, and staffing.

Standardization reduces rework and integration surprises. When interfaces and processes are consistent, a change in one subsystem is less likely to force redesign elsewhere.

It helps by:

The result is faster iteration with less chaos.

By designing tests so failures are contained, instrumented, and informative. The goal isn’t “fail fast” recklessly; it’s to learn quickly without risking people or operational missions.

Good practice includes:

Prototype testing prioritizes learning and may accept higher risk to reveal unknowns quickly. Operational missions prioritize mission success, customer impact, and stability—changes are managed conservatively.

Keeping these separate lets an organization move fast during development while protecting reliability when delivering payloads.

Reusability only lowers marginal cost if refurbishment is fast and predictable. A booster that needs extensive teardown and rework becomes schedule-limited rather than cost-saving.

Keys to making reuse pay off:

Regulation, range availability, and mission assurance requirements set hard constraints on how quickly you can fly and how fast you can change designs.

Cadence can be limited by:

Fast iteration still helps—but more learning must shift to ground testing and controlled change management as requirements tighten.