Dec 09, 2025·8 min

SQL vs NoSQL Databases: Key Differences and Use Cases

Learn the real differences between SQL and NoSQL databases: data models, scalability, consistency, and when each type works best for your applications.

Learn the real differences between SQL and NoSQL databases: data models, scalability, consistency, and when each type works best for your applications.

Choosing between SQL and NoSQL databases shapes how you design, build, and scale your application. The database model influences everything from data structures and query patterns to performance, reliability, and how quickly your team can evolve the product.

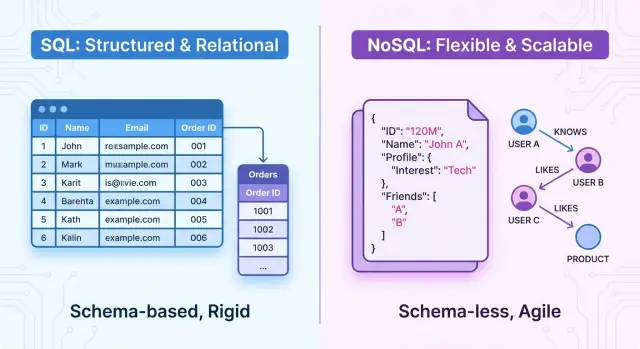

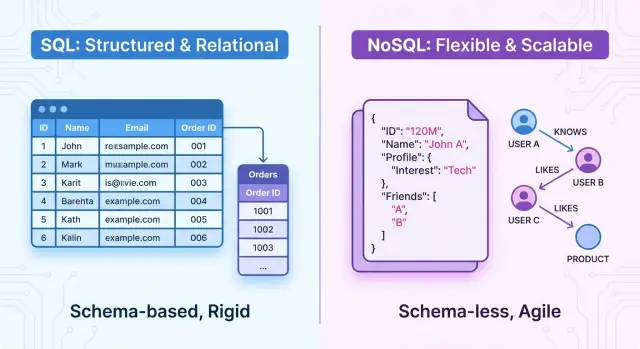

At a high level, SQL databases are relational systems. Data is organized into tables with fixed schemas, rows, and columns. Relationships between entities are explicit (through foreign keys), and you query data using SQL, a powerful declarative language. These systems emphasize ACID transactions, strong consistency, and well-defined structure.

NoSQL databases are non-relational systems. Instead of a single rigid table model, they offer several data models designed for different needs, such as:

That means “NoSQL” is not one technology but an umbrella term for multiple approaches, each with its own trade-offs in flexibility, performance, and data modeling. Many NoSQL systems relax strict consistency guarantees in favor of high scalability, availability, or low latency.

This article focuses on the difference between SQL and NoSQL—data models, query languages, performance, scalability, and consistency (ACID vs eventual consistency). The aim is to help you choose between SQL and NoSQL for specific projects and understand when each type of database fits best.

You don’t have to pick just one, though. Many modern architectures use polyglot persistence, where SQL and NoSQL databases coexist in one system, each handling the workloads they are best at.

An SQL (relational) database stores data in a structured, tabular form and uses Structured Query Language (SQL) to define, query, and manipulate that data. It is built around the mathematical concept of relations, which you can think of as well-organized tables.

Data is organized into tables. Each table represents one type of entity, such as customers, orders, or products.

email or order_date.Every table follows a fixed schema: a predefined structure that specifies

INTEGER, VARCHAR, DATE)NOT NULL, UNIQUE)The schema is enforced by the database, which helps keep data consistent and predictable.

Relational databases excel at modeling how entities relate to one another.

customer_id).These keys allow you to define relationships such as:

Relational databases support transactions—groups of operations that behave as a single unit. Transactions are defined by the ACID properties:

These guarantees are crucial for financial systems, inventory management, and any application where correctness matters.

Popular relational database systems include:

All of them implement SQL, while adding their own extensions and tooling for administration, performance tuning, and security.

NoSQL databases are non-relational data stores that do not use the traditional table–row–column model of SQL systems. Instead, they focus on flexible data models, horizontal scalability, and high availability, often at the cost of strict transactional guarantees.

Many NoSQL databases are described as schema-less or schema-flexible. Instead of defining a rigid schema up front, you can store records with different fields or structures in the same collection or bucket.

This is especially useful for:

Because fields can be added or omitted per record, developers can iterate quickly without running migrations for every structural change.

NoSQL is an umbrella term covering several distinct models:

Many NoSQL systems prioritize availability and partition tolerance, providing eventual consistency instead of strict ACID transactions across the whole dataset. Some offer tunable consistency levels or limited transactional features (per document, partition, or key range), so you can choose between stronger guarantees and higher performance for specific operations.

Data modeling is where SQL and NoSQL feel the most different. It shapes how you design features, query data, and evolve your application.

SQL databases use structured, predefined schemas. You design tables and columns up front, with strict types and constraints:

CREATE TABLE users (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE orders (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

user_id INT NOT NULL,

total DECIMAL(10, 2) NOT NULL,

FOREIGN KEY (user_id) REFERENCES users(id)

);

Every row must follow the schema. Changing it later usually means migrations (ALTER TABLE, backfilling data, etc.).

NoSQL databases typically support flexible schemas. A document store might allow each document to have different fields:

{

"_id": 1,

"name": "Alice",

"orders": [

{ "id": 101, "total": 49.99 },

{ "id": 102, "total": 15.50 }

]

}

Fields can be added per document without a central schema migration. Some NoSQL systems still use optional or enforced schemas, but they are generally looser.

Relational models encourage normalization: splitting data into related tables to avoid duplication and keep integrity. This favors fast, consistent writes and smaller storage, but complex reads might require joins across many tables.

NoSQL models often favor denormalization: embedding related data together for the reads you care about most. This improves read performance and simplifies queries, but writes can be slower or more complex because the same information may live in multiple places.

In SQL, relationships are explicit and enforced:

In NoSQL, relationships are modeled by:

The choice is dictated by your access patterns:

With SQL, schema changes demand more planning but give you strong guarantees and consistency across the dataset. Refactors are explicit: migrations, backfills, constraint updates.

With NoSQL, evolving requirements are usually easier to support in the short term. You can start storing new fields immediately and gradually update old documents. The trade-off is that application code must handle multiple document shapes and edge cases.

Choosing between normalized SQL models and denormalized NoSQL models is less about “better or worse” and more about aligning data structure with your query patterns, write volume, and how often your domain model changes.

SQL databases are queried with a declarative language: you describe what you want, not how to fetch it. Core constructs like SELECT, WHERE, JOIN, GROUP BY, and ORDER BY let you express complex questions over multiple tables in a single statement.

Because SQL is standardized (ANSI/ISO), most relational systems share a common core syntax. Vendors add their own extensions, but skills and queries often transfer reasonably well between PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server, and others.

This standardization brings a rich ecosystem of tools: ORMs, query builders, reporting tools, BI dashboards, migration frameworks, and query optimizers. You can plug many of these into any SQL database with minimal changes, which reduces vendor lock-in and speeds up development.

NoSQL systems expose queries in more varied ways:

Some NoSQL databases offer aggregation pipelines or MapReduce-like mechanisms for analytics, but cross-collection or cross-partition joins are limited or absent. Instead, related data is often embedded in the same document or denormalized across records.

Relational queries often rely on JOIN-heavy patterns: normalize data, then reconstruct entities at read time with joins. This is powerful for ad hoc reporting and evolving questions, but complex joins can be harder to optimize and understand.

NoSQL access patterns tend to be document- or key-centric: design data around the application’s most frequent queries. Reads are fast and simple—often a single key lookup—but changing access patterns later can require reshaping data.

For learning and productivity:

Teams that need rich, ad hoc querying across relationships usually favor SQL. Teams with stable, predictable access patterns at very high scale often find NoSQL query models more aligned with their needs.

Most SQL databases are designed around ACID transactions:

This makes SQL databases a strong fit when correctness is more important than raw write throughput.

Many NoSQL databases lean toward BASE properties:

Writes can be very fast and distributed, but a read might briefly see stale data.

CAP says a distributed system under network partitions must choose between:

You cannot guarantee both C and A during a partition.

Typical patterns:

Modern systems often mix modes (e.g., tunable consistency per operation) so different parts of an application can choose the guarantees they need.

Traditional SQL databases are designed for a single, powerful node.

You typically start by scaling vertically: adding more CPU, RAM, and faster disks to one server. Many engines also support read replicas: additional nodes that accept read-only traffic while all writes go to the primary. This pattern works well for:

However, vertical scaling hits hardware and cost limits, and read replicas can introduce replication lag for reads.

NoSQL systems are usually built for horizontal scaling: spreading data across many nodes using sharding or partitioning. Each shard holds a subset of the data, so both reads and writes can be distributed, increasing throughput.

This approach suits:

The trade-off is higher operational complexity: choosing shard keys, handling rebalancing, and dealing with cross-shard queries.

For read-heavy workloads with complex joins and aggregations, an SQL database with well-designed indexes can be extremely fast, as the optimizer uses statistics and query plans.

Many NoSQL systems favor simple, key-based access patterns. They excel at low-latency lookups and high throughput when queries are predictable and data is modeled around access patterns rather than ad-hoc queries.

Latency in NoSQL clusters can be very low, but cross-partition queries, secondary indexes, and multi-document operations may be slower or more limited. Operationally, scaling NoSQL often means more cluster management, while scaling SQL often means more hardware and careful indexing on fewer nodes.

Relational databases shine when you need reliable, high‑volume OLTP (online transaction processing):

These systems rely on ACID transactions, strict consistency, and clear rollback behavior. If a transfer must never double‑charge or lose money between two accounts, an SQL database is usually safer than most NoSQL options.

When your data model is well understood and stable, and entities are heavily interrelated, a relational database is often the natural fit. Examples:

SQL’s normalized schemas, foreign keys, and joins make it easier to enforce data integrity and query complex relationships without duplicating data.

For reporting and BI over clearly structured data (star/snowflake schemas, data marts), SQL databases and SQL‑compatible warehouses are usually the preferred choice. Analytical teams know SQL, and existing tools (dashboards, ETL, governance) integrate directly with relational systems.

Relational vs non relational database debates often overlook operational maturity. SQL databases offer:

When audits, certifications, or legal exposure are significant concerns, an SQL database is often the more straightforward and defensible choice in the SQL vs NoSQL trade‑off.

NoSQL databases tend to be a better fit when scale, flexibility, and always-on access matter more than complex joins and strict transactional guarantees.

If you expect massive write volume, unpredictable traffic spikes, or datasets that grow into terabytes and beyond, NoSQL systems (like key-value or wide-column stores) are often easier to scale horizontally. Sharding and replication are usually built-in, letting you add capacity by adding nodes instead of constantly re-architecting a single powerful server.

This is a common pattern for:

When your data model changes frequently, a flexible or schema-less design is valuable. Document databases let you evolve fields and structures without migrations for every change.

This works well for:

NoSQL stores are also strong for append-heavy and time-ordered workloads:

Key-value and time-series databases in particular are tuned for very fast writes and simple reads.

Many NoSQL platforms prioritize geo-replication and multi-region writes, allowing users around the world to read and write with low latency. This is useful when:

The trade-off is that you often accept eventual consistency instead of strict ACID semantics across regions.

Choosing NoSQL often means giving up some features you might take for granted in SQL:

When these trade-offs are acceptable, NoSQL can deliver better scalability, flexibility, and global reach than a traditional relational database.

Polyglot persistence means deliberately using multiple database technologies in the same system, choosing the best tool for each job rather than forcing everything into one store.

A common pattern is:

This keeps the “system of record” in a relational database, while offloading volatile or read‑heavy workloads to NoSQL.

You can also combine NoSQL systems:

The goal is to align each datastore with a specific access pattern: simple lookups, aggregates, search, or time‑based reads.

Hybrid architectures rely on integration points:

The trade‑off is operational overhead: more technologies to learn, monitor, secure, back up, and troubleshoot. Polyglot persistence works best when each extra datastore clearly solves a real, measurable problem—not just because it seems modern or interesting.

Choosing between SQL and NoSQL is about matching your data and access patterns to the right tool, not following a trend.

Ask:

If yes, a relational SQL database is usually the default. If your data is document‑like, nested, or varies a lot from record to record, a document or other NoSQL model might fit better.

Strict consistency and complex transactions usually favor SQL. High write throughput with relaxed consistency can favor NoSQL.

Most projects can scale far with SQL using good indexing and hardware. If you anticipate very large scale with simple access patterns (key‑value lookups, time‑series, logs), certain NoSQL systems may be more economical.

SQL shines for complex queries, BI tools, and ad‑hoc exploration. Many NoSQL databases are optimized for predefined access paths and can make new query types harder or more expensive.

Favor technologies your team can operate confidently, especially for production troubleshooting and migrations.

A single managed SQL database is often cheaper and simpler until you clearly outgrow it.

Before committing:

Use those measurements—not assumptions—to choose. For many projects, starting with SQL is the safest path, with the option to introduce NoSQL components later for very specific, high‑scale or specialized use cases.

NoSQL didn’t arrive to kill relational databases; it arrived to complement them.

Relational databases still dominate for systems of record: finance, HR, ERP, inventory, and any workflow where strict consistency and rich transactions matter. NoSQL databases shine where flexible schemas, huge write throughput, or globally distributed reads are more important than complex joins and strict ACID guarantees.

Most organizations end up using both, picking the right tool for each workload.

Relational databases have historically scaled up on bigger servers, but modern engines support:

Scaling a relational system can be more involved than adding nodes to some NoSQL clusters, but horizontal scale is absolutely possible with the right design and tooling.

“Schema-less” really means “schema is enforced by the application, not the database.”

Document, key–value, and wide-column stores still have structure. They just allow that structure to evolve per record or per collection. This flexibility is powerful, but without clear data contracts, governance, and validation, it quickly leads to inconsistent data.

Performance depends far more on data modeling, indexing, and access patterns than on “SQL vs NoSQL.”

A poorly indexed NoSQL collection will be slower than a well-tuned relational table for many queries. Likewise, a relational schema that ignores query patterns will underperform compared to a NoSQL model tailored to those queries.

Many NoSQL databases support strong durability, encryption, auditing, and access control. Conversely, a misconfigured relational database can be insecure and fragile.

Security and reliability are properties of the specific product, deployment, configuration, and operational maturity—not of “SQL” or “NoSQL” as categories.

Teams usually move between SQL and NoSQL for two reasons: scaling and flexibility. A high‑traffic product might keep a relational database as the trusted system of record, then introduce NoSQL to handle reads at scale or to support new features with more flexible schemas.

A big‑bang migration from SQL to NoSQL (or the reverse) is risky. Safer options include:

Moving from SQL to a non‑relational database tempts teams to mirror tables as documents or key‑value pairs. That often leads to:

Plan the new access patterns first, then design the NoSQL schema around actual queries.

A common pattern is SQL for authoritative data (billing, user accounts) and NoSQL for read‑heavy views (feeds, search, caching). Whatever the mix, invest in:

This keeps SQL vs NoSQL migrations controlled rather than painful one‑way moves.

SQL and NoSQL differ mainly in four areas:

Neither category is universally better. The “right” choice depends on your actual requirements, not on trends or slogans.

Write down your needs:

Default sensibly:

Start small and measure:

Stay open to hybrids:

/docs/architecture/datastores).For deeper dives, extend this overview with internal standards, migration checklists, and further reading in your engineering handbook or /blog.

SQL (relational) databases:

NoSQL (non‑relational) databases:

Use an SQL database when:

For most new business systems of record, SQL is a sensible default.

NoSQL fits best when:

SQL databases:

NoSQL databases:

SQL databases:

Many NoSQL systems:

Choose SQL when stale reads are dangerous; choose NoSQL when brief staleness is acceptable in exchange for scale and uptime.

SQL databases typically:

NoSQL databases typically:

Yes. Polyglot persistence is common:

Integration patterns include:

The key is to add each extra datastore only when it solves a clear problem.

To move gradually and safely:

Avoid big‑bang migrations; prefer incremental, well‑monitored steps.

Consider:

Common misconceptions include:

Evaluate specific products and architectures instead of relying on category‑level myths.

This means schema control moves from the database (SQL) to the application (NoSQL).

The trade‑off is that NoSQL clusters are operationally more complex, while SQL can hit limits on a single node sooner.

Prototype both options for critical flows and measure latency, throughput, and complexity before deciding.