Aug 02, 2025·8 min

Andrew S. Tanenbaum’s MINIX: Teaching Kernel Design Clearly

Learn how Andrew S. Tanenbaum built MINIX to teach OS internals, and what its microkernel approach explains about kernel structure and design tradeoffs.

Learn how Andrew S. Tanenbaum built MINIX to teach OS internals, and what its microkernel approach explains about kernel structure and design tradeoffs.

MINIX is a small, teaching-focused operating system created by Andrew S. Tanenbaum to make the “inside” of an operating system understandable. It’s not trying to win benchmarks or ship on millions of laptops. It’s trying to be readable, testable, and explainable—so you can study kernel design without getting lost in a huge codebase.

Studying kernels pays off even if you never plan to write one. The kernel is where core decisions about performance (how quickly work gets done) and reliability (how well the system survives bugs and failures) are made. Once you understand what a kernel is responsible for—scheduling, memory, device access, and security boundaries—you start to reason about everyday engineering questions differently:

This article uses MINIX as a clear, structured example of kernel architecture. You’ll learn the key concepts and the tradeoffs behind them, with plain explanations and minimal jargon.

You won’t need deep math, and you won’t need to memorize theoretical models. Instead, you’ll build a practical mental model of how an OS is split into parts, how those parts communicate, and what you gain (and lose) with different designs.

We’ll cover:

By the end, you should be able to look at any operating system and quickly identify the design choices underneath—and what they imply.

Andrew S. Tanenbaum is one of the most influential voices in operating-systems education—not because he built a commercial kernel, but because he optimized for how people learn kernels. As a professor and author of widely used OS textbooks, he treated an operating system as a teaching instrument: something students should be able to read, reason about, and modify without getting lost.

Many real-world operating systems are engineered under pressures that don’t help beginners: performance tuning, backwards compatibility, huge hardware matrices, and years of layered features. Tanenbaum’s goal with MINIX was different. He wanted a small, understandable system that made core OS ideas visible—processes, memory management, file systems, and inter-process communication—without requiring students to sift through millions of lines of code.

That “inspectable” mindset matters. When you can trace a concept from a diagram to the actual source, you stop treating the kernel like magic and start treating it like design.

Tanenbaum’s textbook explanations and MINIX reinforce each other: the book provides a mental model, and the system provides concrete proof. Students can read a chapter, then locate the corresponding mechanism in MINIX and see how the idea survives contact with reality—data structures, message flows, and error handling included.

This pairing also makes assignments practical. Instead of only answering theoretical questions, learners can implement a change, run it, and observe the consequences.

A teaching operating system prioritizes clarity and simplicity, with source availability and stable interfaces that encourage experimentation. MINIX is intentionally designed to be read and changed by newcomers—while still being realistic enough to teach the tradeoffs that every kernel must make.

By the mid–late 1980s, UNIX ideas were spreading through universities: processes, files-as-streams, pipes, permissions, and the notion that an operating system could be studied as a coherent set of concepts—not just as a vendor black box.

The catch was practical. The UNIX systems that existed on campus were either too expensive, too legally restricted, or too large and messy to hand to students as “readable source code.” If the goal was to teach kernel design, a course needed something students could actually compile, run, and understand within a semester.

MINIX was built to be a teaching operating system that felt familiar to anyone who had used UNIX, while staying intentionally small. That combination matters: it let instructors teach standard OS topics (system calls, process management, file systems, device I/O) without forcing students to learn a completely alien environment first.

At a high level, MINIX aimed for compatibility in the ways that help learning:

read()” down to “bytes arrive from disk”MINIX’s defining constraints weren’t an accident—they were the point.

So the “problem” MINIX solved wasn’t simply “make another UNIX.” It was: build a UNIX-like system optimized for learning—compact, understandable, and close enough to real-world interfaces that the lessons transfer.

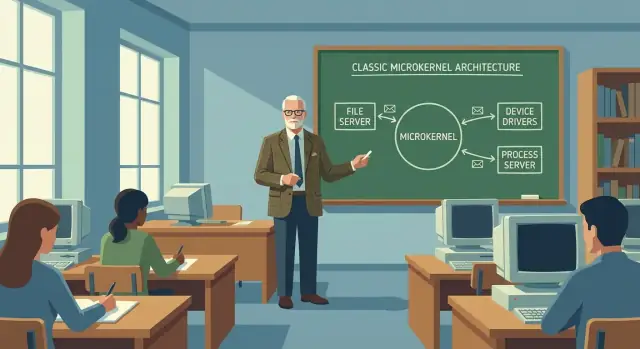

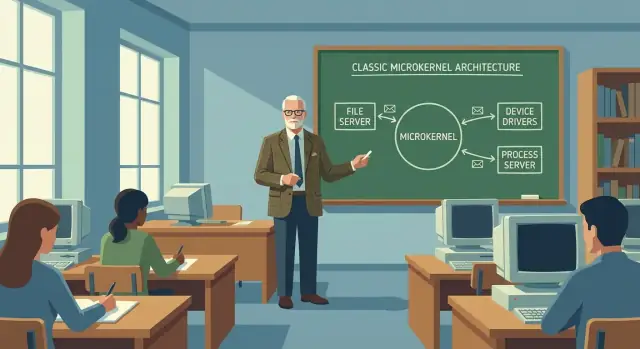

A microkernel is a kernel that stays small on purpose. Instead of packing every operating-system feature into one privileged blob, it keeps only the essentials in “kernel mode” and pushes most other work into normal user-space programs.

In plain terms: the microkernel is the thin referee that enforces rules and passes notes between players, rather than being the entire team.

MINIX’s microkernel keeps a short list of responsibilities that truly need full hardware privilege:

This small core is easier to read, test, and reason about—exactly what you want in a teaching operating system.

Many components people casually call “the OS” run as separate user-space servers in MINIX:

These are still part of the operating system, but they behave like ordinary programs with limited privileges. If one crashes, it’s less likely to take the whole machine down.

In a monolithic kernel, the file system might call a driver using a direct function call inside the same privileged codebase. In MINIX, the file system server typically sends a message to a driver server instead.

That changes how you think about design: you define interfaces (“what messages exist, what data they carry, what replies mean”) rather than sharing internal data structures across the whole kernel.

The microkernel approach buys fault isolation and cleaner boundaries, but it introduces costs:

MINIX is valuable because you can see these tradeoffs directly, not as theory—small core, clear interfaces, and an architecture that makes consequences visible.

MINIX is easier to reason about because it draws clear boundaries between what must be trusted and what can be treated like a normal program. Instead of putting most OS code in one big kernel, MINIX splits responsibilities across several components that communicate through well-defined interfaces.

At a high level, MINIX is organized into:

This split is a practical demonstration of separation of concerns: each piece has a narrower job, and students can study one part without needing to mentally load the entire OS.

When a user program calls something like “read from this file,” the request typically travels:

MINIX makes a useful distinction: the kernel mostly offers mechanisms (the tools: scheduling primitives, message passing), while policies (the rules: which process gets what, how files are organized) live in servers. That separation helps learners see how changing “rules” doesn’t require rewriting the most trusted core.

A microkernel pushes most “OS work” into separate processes (like file systems, device drivers, and servers). That only works if those parts can talk to each other reliably. In MINIX, that conversation is message passing, and it’s central because it turns kernel design into an exercise in interfaces rather than hidden shared state.

At a high level, message passing means one component sends a structured request to another—“open this file,” “read these bytes,” “give me the current time”—and receives a structured reply. Instead of directly calling internal functions or poking shared memory, each subsystem must go through a defined channel. That separation is the teaching win: you can point to a boundary and say, “Everything across this boundary is a message.”

Synchronous messaging is like a phone call: the sender waits until the receiver handles the request and responds. It’s simple to reason about because the flow is linear.

Asynchronous messaging is more like email: you send a request and continue working, receiving responses later. It can improve responsiveness and concurrency, but students must now track pending requests, ordering, and timeouts.

IPC adds overhead: packaging data, switching context, validating permissions, and copying or mapping buffers. MINIX makes that cost visible, which helps students understand why some systems prefer monolithic designs.

On the other hand, debugging often gets easier. When failures happen at clear message boundaries, you can log requests and replies, reproduce sequences, and isolate which server misbehaved—without assuming “the kernel is one big blob.”

Clear IPC interfaces force disciplined thinking: what inputs are allowed, what errors can occur, and what state is private. Students learn to design kernels the way they design networks: contracts first, implementation second.

MINIX becomes “real” for students when it stops being diagrams and turns into runnable work: processes that block, schedules that shift under load, and memory limits you can actually hit. These are the pieces that make an operating system feel physical.

A process is the OS’s container for a running program: its CPU state, its address space, and its resources. In MINIX, you learn quickly that “a program running” is not a single thing—it’s a bundle of tracked state the kernel can start, pause, resume, and stop.

That matters because nearly every OS policy (who runs next, who can access what, what happens on failure) is expressed in terms of processes.

Scheduling is the rulebook for CPU time. MINIX makes scheduling feel concrete: when many processes want to run, the OS must choose an order and a slice of time. Small choices show up as visible outcomes:

In a microkernel-style system, scheduling also interacts with communication: if a service process is delayed, everything waiting on its reply feels slower.

Memory management decides how processes get RAM and what they’re allowed to touch. It’s the boundary that prevents one process from scribbling over another.

In MINIX’s architecture, memory-related work is split: the kernel enforces low-level protection, while higher-level policies can live in services. That split highlights a key teaching point: separating enforcement from decision-making makes the system easier to analyze—and easier to change safely.

If a user-space service crashes, MINIX can often keep the kernel alive and the rest of the system running—failure becomes contained. In a more monolithic design, the same bug in privileged code may crash the entire kernel.

That single difference connects design decisions to outcomes: isolation improves safety, but it can add overhead and complexity in coordination. MINIX makes you feel that tradeoff, not just read about it.

Kernel debates often sound like a boxing match: microkernel versus monolithic, pick a side. MINIX is more useful when you treat it as a thinking tool. It highlights that kernel architecture is a spectrum of choices, not a single “correct” answer.

A monolithic kernel keeps many services inside one privileged space—device drivers, file systems, networking, and more. A microkernel keeps the privileged “core” small (scheduling, basic memory management, IPC) and runs the rest as separate user-space processes.

That shift changes the tradeoffs:

General-purpose systems may accept a larger kernel for performance and compatibility (many drivers, many workloads). Systems that prioritize reliability, maintainability, or strong separation (some embedded and security-focused designs) may choose a more microkernel-like structure. MINIX teaches you to justify the choice based on goals, not ideology.

Device drivers are one of the most common reasons an operating system crashes or behaves unpredictably. They sit at an awkward boundary: they need deep access to hardware, they react to interrupts and timing quirks, and they often include a lot of vendor-specific code. In a traditional monolithic kernel, a buggy driver can overwrite kernel memory or get stuck holding a lock—taking the whole system down with it.

MINIX uses a microkernel approach where many drivers run as separate user-space processes rather than as privileged kernel code. The microkernel keeps only the essentials (scheduling, basic memory management, and inter-process communication) and drivers talk to it through well-defined messages.

The teaching benefit is immediate: you can point to a smaller “trusted core” and then show how everything else—drivers included—interacts through interfaces instead of hidden shared memory tricks.

When a driver is isolated:

It turns “the kernel is magic” into “the kernel is a set of contracts.”

Isolation isn’t free. Designing stable driver interfaces is hard, message passing adds overhead compared to direct function calls, and debugging becomes more distributed (“is the bug in the driver, the IPC protocol, or the server?”). MINIX makes those costs visible—so students learn that fault isolation is a deliberate tradeoff, not a slogan.

The famous MINIX vs. Linux discussion is often remembered as a personality clash. It’s more useful to treat it as an architectural debate: what should an operating system optimize for when it’s being built, and what compromises are acceptable?

MINIX was designed primarily as a teaching operating system. Its structure aims to make kernel ideas visible and testable in a classroom: small components, clear boundaries, and behavior you can reason about.

Linux was built with a different target: a practical system people could run, extend quickly, and push for performance on real hardware. Those priorities naturally favor different design choices.

The debate is valuable because it forces a set of timeless questions:

From Tanenbaum’s perspective, you learn to respect interfaces, isolation, and the discipline of keeping the kernel small enough to understand.

From the Linux path, you learn how real-world constraints pressure designs: hardware support, developer velocity, and the benefits of shipping something useful early.

A common myth is that the debate “proved” one architecture is always superior. It didn’t. It highlighted that educational goals and product goals are different, and that smart engineers can argue honestly from different constraints. That’s the lesson worth keeping.

MINIX is often taught less like a “product” and more like a lab instrument: you use it to observe cause-and-effect in a real kernel without drowning in unrelated complexity. A typical course workflow cycles through three activities—read, change, verify—until you build intuition.

Students usually start by tracing a single system action end-to-end (for example: “a program asks the OS to open a file” or “a process goes to sleep and later wakes up”). The goal isn’t to memorize modules; it’s to learn where decisions are made, where data is validated, and which component is responsible for what.

A practical technique is to pick one entry point (a syscall handler, a scheduler decision, or an IPC message) and follow it until the outcome is visible—like a returned error code, a changed process state, or a message reply.

Good starter exercises tend to be tightly scoped:

The key is choosing changes that are easy to reason about and hard to “accidentally succeed” at.

“Success” is being able to predict what your change will do, then confirm it with repeatable tests (and logs when needed). Instructors often grade the explanation as much as the patch: what you changed, why it worked, and what tradeoffs it introduced.

Trace one path end-to-end first, then broaden to adjacent paths. If you jump between subsystems too early, you’ll collect details without building a usable mental model.

MINIX’s lasting value isn’t that you memorize its components—it’s that it trains you to think in boundaries. Once you internalize that systems are made of responsibilities with explicit interfaces, you start seeing hidden coupling (and hidden risks) in any codebase.

First: structure beats cleverness. If you can draw a box diagram that still makes sense a month later, you’re already ahead.

Second: interfaces are where correctness lives. When communication is explicit, you can reason about failure modes, permissions, and performance without reading every line.

Third: every design is a tradeoff. Faster isn’t always better; simpler isn’t always safer. MINIX’s teaching focus makes you practice naming the trade you’re making—and defending it.

Use this mindset in debugging: instead of hunting symptoms, ask “Which boundary was crossed incorrectly?” Then verify assumptions at the interface: inputs, outputs, timeouts, and error handling.

Use it in architecture reviews: list responsibilities, then ask whether any component knows too much about another. If swapping a module requires touching five others, the boundary is probably wrong.

This is also a helpful lens for modern “vibe-coding” workflows. For example, in Koder.ai you can describe an app in chat and have the platform generate a React web frontend, a Go backend, and a PostgreSQL database. The fastest way to get good results is surprisingly MINIX-like: define responsibilities up front (UI vs API vs data), make the contracts explicit (endpoints, messages, error cases), and iterate safely using planning mode plus snapshots/rollback when you refine the boundaries.

If you want to deepen the model, study these topics next:

You don’t need to be a kernel engineer to benefit from MINIX. The core habit is simple: design systems as cooperating parts with explicit contracts—and evaluate choices by the tradeoffs they create.

MINIX is intentionally small and “inspectable,” so you can trace a concept from a diagram to real source code without wading through millions of lines. That makes core kernel responsibilities—scheduling, memory protection, IPC, and device access—easier to study and modify within a semester.

A teaching OS optimizes for clarity and experimentation rather than maximum performance or broad hardware support. That usually means a smaller codebase, stable interfaces, and a structure that encourages reading, changing, and testing parts of the system without getting lost.

The microkernel keeps only the most privilege-sensitive mechanisms in kernel mode, such as:

Everything else (file systems, drivers, many services) is pushed into user-space processes that communicate via messages.

In a microkernel design, many OS components are separate user-space processes. Instead of calling internal kernel functions directly, components send structured IPC messages like “read these bytes” or “write this block,” then wait for a reply (or handle it later). This forces explicit interfaces and reduces hidden shared state.

A typical path is:

read).Following this end-to-end is a good way to build a practical mental model.

A common framing is:

MINIX makes this separation visible, so you can change policies in user space without rewriting the most trusted kernel core.

Synchronous IPC means the sender waits for a reply (simpler control flow, easier to reason about). Asynchronous IPC lets the sender continue and handle replies later (more concurrency, but you must manage ordering, timeouts, and pending requests). When learning, synchronous flows are often easier to trace end-to-end.

Microkernels typically gain:

But they often pay:

MINIX is valuable because you can observe both sides directly in a real system.

Drivers often contain hardware-specific code and are a frequent source of crashes. Running drivers as user-space processes can:

The cost is more IPC and the need for carefully designed driver interfaces.

A practical workflow is:

Keeping changes small helps you learn cause-and-effect instead of debugging a large, unclear patch.