Sep 23, 2025·8 min

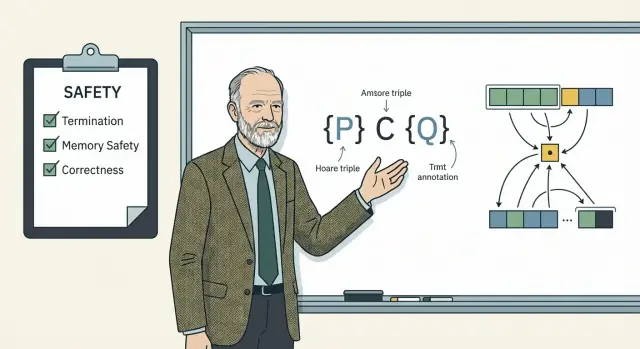

Tony Hoare’s Correctness Ideas: From Logic to Safe Code

Learn how Tony Hoare’s work on Hoare logic, Quicksort, and safety thinking shaped practical techniques for writing and reviewing correct software.

Why “correctness” is more than “it seems to work”

When people say a program is “correct,” they often mean: “I ran it a few times and the output looked right.” That’s a useful signal—but it’s not correctness. In plain terms, correctness means the program meets its specification: for every allowed input, it produces the required result and respects any rules about state changes, timing, and errors.

The catch is that “meets its spec” is harder than it sounds.

Why correctness is genuinely hard

First, specifications are often ambiguous. A product requirement might say “sort the list,” but does that mean stable sorting? What about duplicate values, empty lists, or non-numeric items? If the spec doesn’t say, different people will assume different answers.

Second, edge cases aren’t rare—they’re just less frequently tested. Null values, overflow, off-by-one boundaries, unusual user sequences, and unexpected external failures can turn “it seems to work” into “it failed in production.”

Third, requirements change. A program can be correct relative to yesterday’s spec and incorrect relative to today’s.

What to expect from the rest of this article

Tony Hoare’s big contribution wasn’t the claim that we should prove everything all the time. It was the idea that we can be more precise about what code is supposed to do—and reason about it in a disciplined way.

In this post, we’ll follow three connected threads:

- Hoare logic: lightweight, structured reasoning using preconditions and postconditions.

- Quicksort: a familiar algorithm that exposes how small “obvious” steps (like partitioning) need careful thinking.

- Safety mindset: correctness as a practical responsibility when failures have real consequences.

Most teams won’t write full formal proofs. But even partial, “proof-style” thinking can make bugs easier to spot, reviews sharper, and behavior clearer before code ships.

Tony Hoare in brief: ideas that reached everyday code

Tony Hoare is one of those rare computer scientists whose work didn’t stay in papers or classrooms. He moved between academia and industry, and he cared about a practical question that every team still faces: how do we know a program does what we think it does—especially when the stakes are high?

The contributions that matter for this post

This article focuses on a few Hoare ideas that keep showing up in real codebases:

- Hoare logic: a way to describe program behavior using preconditions, postconditions, and the well-known Hoare triple

{P} C {Q}. - Loop invariants: a disciplined habit for reasoning about loops beyond “it worked on my machine.”

- Quicksort (and especially its partition step): a famous example where a small, precise statement of correctness clarifies a lot.

- Safety thinking: the mindset that correctness isn’t a luxury feature; it can be the difference between inconvenience and harm.

What this post will not do

You won’t find deep mathematical formalism here, and we won’t attempt a complete, machine-checkable proof of Quicksort. The goal is to keep the concepts approachable: enough structure to make your reasoning clearer, without turning your code review into a graduate seminar.

Why his work affects everyday programming

Hoare’s ideas translate into ordinary decisions: what assumptions a function relies on, what it guarantees to callers, what must stay true halfway through a loop, and how to spot “almost correct” changes during reviews. Even when you never write {P} C {Q} explicitly, thinking in that shape improves APIs, tests, and the quality of discussions about tricky code.

What “correctness” means in practice

Hoare’s view is stricter than “it passed a few examples”: correctness is about meeting an agreed promise, not about looking right on a small sample.

Requirements vs. specification vs. implementation

- Requirements are the business need in plain language (what stakeholders want).

- A specification is the precise, checkable version of that need (what the function must do).

- The implementation is the code you wrote (how it does it).

Bugs often happen when teams skip the middle step: they jump from requirements straight to code, leaving the “promise” fuzzy.

Partial correctness vs. total correctness

Two different claims frequently get mixed together:

- Partial correctness: If the code returns, the result is right.

- Total correctness: The code returns, and the result is right. (so termination is part of the claim)

For real systems, “never finishing” can be as harmful as “finishing with the wrong answer.”

Correctness always depends on assumptions

Correctness statements are never universal; they rely on assumptions about:

- Inputs (e.g., the list fits in memory, elements are comparable)

- Constraints (e.g., time limits, integer ranges)

- Environment (e.g., concurrency, I/O failures, configuration)

Being explicit about assumptions turns “works on my machine” into something others can reason about.

A tiny example spec

Consider a function sortedCopy(xs).

A useful spec could be: “Returns a new list ys such that (1) ys is sorted ascending, and (2) ys contains exactly the same elements as xs (same counts), and (3) xs is unchanged.”

Now “correct” means the code satisfies those three points under the stated assumptions—not just that the output looks sorted in a quick test.

Hoare logic basics: preconditions, postconditions, triples

Hoare logic is a way to talk about code with the same clarity you’d use to talk about a contract: if you start in a state that satisfies certain assumptions, and you run this piece of code, you’ll end in a state that satisfies certain guarantees.

The core notation is the Hoare triple:

{precondition} program {postcondition}

Preconditions: what you assume

A precondition states what must be true before the program fragment runs. This isn’t about what you hope is true; it’s what the code needs to be true.

Example: suppose a function returns the average of two numbers without overflow checks.

- Precondition:

a + bfits in the integer type - Program:

avg = (a + b) / 2 - Postcondition:

avgequals the mathematical average ofaandb

If the precondition doesn’t hold (overflow is possible), the postcondition promise no longer applies. The triple forces you to say that out loud.

Postconditions: what you guarantee

A postcondition states what will be true after the code runs—assuming the precondition was met. Good postconditions are concrete and checkable. Instead of “result is valid,” say what “valid” means: sorted, non-negative, within bounds, unchanged except for specific fields, etc.

Assignment and sequencing (without the symbolism overload)

Hoare logic scales from tiny statements to multi-step code:

- Assignment changes the state in a precise way. Reasoning asks: after

x = x + 1, what facts aboutxare now true? - Sequencing (“do this, then that”) chains guarantees: if step 1 establishes the precondition for step 2, the whole block becomes easier to trust.

The point isn’t to sprinkle curly braces everywhere. It’s to make intent readable: clear assumptions, clear outcomes, and fewer “it seems to work” conversations in reviews.

Loop invariants that real teams can write

A loop invariant is a statement that is true before the loop starts, remains true after every iteration, and is still true when the loop finishes. It’s a simple idea with a big payoff: it replaces “it seems to work” with a claim you can actually check at each step.

Why invariants stop hand-wavy reasoning

Without an invariant, a review often sounds like: “We iterate over the list and gradually fix things.” An invariant forces precision: what exactly is already correct right now, even though the loop isn’t done? Once you can say that clearly, off-by-one errors and missing cases become easier to spot, because they show up as moments where the invariant would be broken.

Invariant templates you can reuse

Most day-to-day code can use a few reliable templates.

1) Bounds / index safety

Keep indices in a safe range.

0 <= i <= nlow <= left <= right <= high

This type of invariant is great for preventing out-of-range access and for making array reasoning concrete.

2) Processed vs. unprocessed items

Split your data into a “done” region and a “not yet” region.

- “All elements in

a[0..i)have been examined.” - “Every item moved to

resultsatisfies the filter predicate.”

This turns vague progress into a clear contract about what “processed” means.

3) Sorted prefix (or partitioned prefix)

Common in sorting, merging, and partitioning.

- “

a[0..i)is sorted.” - “All items in

a[0..i)are<= pivot, and all items ina[j..n)are>= pivot.”

Even if the full array isn’t sorted yet, you’ve pinned down what is.

Termination in plain terms: a measure that shrinks

Correctness isn’t just about being right; the loop must also finish. A simple way to argue that is to name a measure (often called a variant) that decreases each iteration and can’t decrease forever.

Examples:

- “

n - ishrinks by 1 each time.” - “The number of unprocessed items decreases.”

If you can’t find a shrinking measure, you may have discovered a real risk: an infinite loop on some inputs.

Quicksort as a case study in reasoning about code

Deploy and Validate Edge Cases

Deploy your generated app to try real edge cases and failure paths, not just happy flows.

Quicksort has a simple promise: given a slice (or array segment), rearrange its elements so they end up in non-decreasing order, without losing or inventing any values. The algorithm’s high-level shape is easy to summarize:

- Choose a pivot value.

- Partition the range so elements “less than pivot” move to one side and “greater than pivot” move to the other (with some rule for “equal”).

- Recurse on the left and right subranges.

It’s a great teaching example for correctness because it’s small enough to hold in your head, but rich enough to show where informal reasoning fails. A Quicksort that “seems to work” on a few random tests can still be wrong in ways that only show up under specific inputs or boundary conditions.

The pitfalls that break “obvious” implementations

A few issues cause most bugs:

- Duplicates: If your partition treats “equal to pivot” inconsistently, you can end up with infinite recursion (subranges don’t shrink) or a partition that violates its own rule.

- Empty or one-element ranges: The base case must be precise; otherwise you’ll index out of bounds or recurse forever.

- Off-by-one indices: Partition algorithms often use two pointers; a single wrong comparison or increment can skip elements or swap outside the range.

What actually must be proven

To argue correctness in a Hoare-style way, you typically separate the proof into two parts:

- Partition correctness: after partitioning, every element on the left satisfies the chosen relation to the pivot, every element on the right satisfies the opposite relation, and the result is a permutation of the original elements.

- Recursion correctness: recursive calls operate on strictly smaller ranges (termination) and, assuming they sort their subranges, the whole range ends up sorted.

This separation keeps the reasoning manageable: get partition right, then build sorting correctness on top of it.

Partition correctness: the heart of Quicksort

Quicksort’s speed depends on one deceptively small routine: partition. If partition is even slightly wrong, Quicksort can mis-sort, loop forever, or crash on edge cases.

The partition contract (what it must guarantee)

We’ll use the classic Hoare partition scheme (two pointers moving inward).

Input: an array slice A[lo..hi] and a chosen pivot value (often A[lo]).

Output: an index p such that:

- every element in

A[lo..p]is <= pivot - every element in

A[p+1..hi]is >= pivot

Notice what’s not promised: the pivot doesn’t necessarily end up at position p, and elements equal to the pivot may appear on either side. That’s okay—Quicksort only needs a correct split.

Key invariants while scanning and swapping

As the algorithm advances two indices—i from the left, j from the right—good reasoning focuses on what is already “locked in.” A practical set of invariants is:

- all items in

A[lo..i-1]are <= pivot (left side is clean) - all items in

A[j+1..hi]are >= pivot (right side is clean) - everything in

A[i..j]is unclassified (still to be checked)

When we find A[i] >= pivot and A[j] <= pivot, swapping them preserves those invariants and shrinks the unclassified middle.

Edge cases that correctness must cover

- All smaller than pivot:

iruns to the right; partition must still terminate and return a sensiblep. - All larger than pivot:

jruns to the left; same termination concern. - Many equals: if comparisons are inconsistent (

<vs<=), pointers can stall. Hoare’s scheme relies on a consistent rule so progress continues. - Already sorted / reverse sorted: shouldn’t break the contract, even if performance degrades.

Different partition schemes exist (Lomuto, Hoare, three-way partitioning). The key is to pick one, state its contract, and review the code against that contract consistently.

Reasoning about recursion: base cases and termination

Scaffold Go and Postgres APIs

Turn a clear spec into a Go API and PostgreSQL schema you can refine with your team.

Recursion is easiest to trust when you can answer two questions clearly: when does it stop? and why is each step valid? Hoare-style thinking helps because it forces you to state what must be true before a call, and what will be true after it returns.

The base case must be correct

A recursive function needs at least one base case where it does no further recursive calls and still satisfies the promised result.

For sorting, a typical base case is “arrays of length 0 or 1 are already sorted.” Here, “sorted” should be explicit: for an ordering relation ≤, the output array is sorted if for every index i < j, we have a[i] ≤ a[j]. (Whether equal elements keep their original order is a separate property called stability; Quicksort is not usually stable unless you design it to be.)

The subproblem must shrink

Every recursive step should call itself on a strictly smaller input. This “shrinking” is your termination argument: if the size decreases and cannot go below 0, you can’t recurse forever.

Shrinking also matters for stack safety. Even correct code can crash if recursion depth gets too large. In Quicksort, unbalanced partitions can produce deep recursion. That’s a termination-proof plus a practical reminder to consider worst-case depth.

Correctness first, performance second

Quicksort’s worst-case time can degrade to O(n²) when partitions are very unbalanced, but that’s a performance concern—not a correctness failure. The reasoning goal here is: assuming the partition step preserves elements and splits them according to the pivot, recursive sorting of the smaller parts implies the whole array meets the definition of sortedness.

Proof-style thinking and testing: how they fit together

Testing and proof-style reasoning aim at the same goal—confidence—but they get there differently.

Testing finds bugs; reasoning rules out classes of bugs

Tests are excellent at catching concrete mistakes: an off-by-one, a missing edge case, a regression. But a test suite can only sample the input space. Even “100% coverage” doesn’t mean “all behaviors checked”; it mostly means “all lines executed.”

Proof-style thinking (Hoare-style reasoning in particular) starts from a specification and asks: if these preconditions hold, does the code always establish the postconditions? When you do that well, you don’t just find a bug—you can often eliminate an entire category of bugs (like “array access stays in bounds” or “the loop never breaks the partition property”).

Specifications produce better test cases

A clear spec is a test generator.

If your postcondition says “output is sorted and is a permutation of the input,” you automatically get test ideas:

- Boundaries: empty list, one element, already sorted, reverse sorted.

- Invariants: intermediate properties (e.g., partition keeps elements <= pivot on the left).

- Invalid inputs: nulls, NaN values, out-of-range indices, inconsistent comparators.

The spec tells you what “correct” means, and the tests check that reality matches it.

Property-based tests as the practical bridge

Property-based testing sits between proofs and examples. Instead of hand-picking a few cases, you state properties and let a tool generate many inputs.

For sorting, two simple properties go a long way:

- Sortedness: the result is in non-decreasing order.

- Permutation: the result contains exactly the same elements as the input.

These properties are essentially postconditions written as executable checks.

A workflow teams can actually use

A lightweight routine that scales:

- Write a spec first (preconditions, postconditions, key invariants).

- Reason about the tricky parts (loops, partitioning, recursion boundaries).

- Turn the spec into tests (boundary cases + property-based checks).

- Keep them together in code and reviews, so future changes don’t quietly violate the original intent.

If you want a place to institutionalize this, make “spec + reasoning notes + tests” part of your PR template or code review checklist (see also /blog/code-review-checklist).

If you’re using a vibe-coding workflow (generating code from a chat-based interface), the same discipline applies—arguably more so. In Koder.ai, for example, you can start in Planning Mode to pin down preconditions/postconditions before any code is generated, then iterate with snapshots and rollback while you add property-based tests. The tool speeds up implementation, but the spec is still what keeps “fast” from turning into “fragile.”

Safety thinking: correctness with real-world consequences

Correctness isn’t only about “the program returns the right value.” Safety thinking asks a different question: what outcomes are unacceptable, and how do we prevent them—even when code is stressed, misused, or partially failing? In practice, safety is correctness with a priority system: some failures are merely annoying, others can cause financial loss, privacy breaches, or physical harm.

Hazards vs. bugs: why impact matters

A bug is a defect in the code or design. A hazard is a situation that can lead to an unacceptable outcome. One bug can be harmless in one context and dangerous in another.

Example: an off-by-one error in a photo gallery might mislabel an image; the same error in a medication dosage calculator could harm a patient. Safety thinking forces you to connect code behavior to consequences, not just to “spec compliance.”

Simple techniques that prevent the worst outcomes

You don’t need heavy formal methods to get immediate safety benefits. Teams can adopt small, repeatable practices:

- Fail-safe defaults: if the system can’t be confident, choose the safer behavior. For instance, deny access when authorization checks fail rather than “allow on error.”

- Input validation at boundaries: treat user input, file contents, and network data as untrusted. Validate types, ranges, formats, and invariants early.

- Limits and timeouts: cap memory use, request sizes, recursion depth, retries, and execution time. Many incidents are “correct” code running with unreasonable inputs.

These techniques pair naturally with Hoare-style reasoning: you make preconditions explicit (what inputs are acceptable) and ensure postconditions include safety properties (what must never happen).

Trade-offs: checks aren’t free

Safety-oriented checks cost something—CPU time, complexity, or occasional false rejections.

- Performance vs. checks: fast paths are valuable, but critical boundaries deserve validation, rate limits, and timeouts.

- Strictness vs. usability: rejecting all imperfect input can frustrate users; accepting everything can create ambiguity and exploitation. A practical compromise is “be strict at the core, forgiving at the edges,” while logging and measuring how often edge cases occur.

Safety thinking is less about proving elegance and more about preventing the failure modes you can’t afford.

Applying Hoare-style reasoning in code reviews

Make Reviews Less Hand Wavy

Turn review questions into a short checklist: assumptions in, guarantees out, and termination.

Code reviews are where correctness thinking pays off fastest, because you can spot missing assumptions long before bugs reach production. Hoare’s core move—stating what must be true before and what will be true after—translates neatly into review questions.

Turn Hoare ideas into review questions

When you read a change, try framing each key function as a tiny promise:

- Assumptions (preconditions): What must be true about inputs, state, and environment? (e.g., “list is non-empty”, “user is authenticated”, “lock is held”).

- Guarantees (postconditions): What is true afterward, including returned values and side effects? (e.g., “balance decreased by amount”, “record inserted exactly once”).

- Invariants: What must remain true throughout a loop, retry, or multi-step workflow? (e.g., “processed_count ≤ total”, “sum of debits equals sum of credits so far”).

- Failure behavior: What happens on errors—do we leave the system in a safe state? Are partial updates rolled back?

A simple reviewer habit: if you can’t say the pre/post conditions in one sentence, the code likely needs clearer structure.

“Contract comments” for critical functions

For risky or central functions, add a small contract comment right above the signature. Keep it concrete: inputs, outputs, side effects, and errors.

def withdraw(account, amount):

"""Contract:

Pre: amount is an integer > 0; account is active.

Post (success): returns new_balance; account.balance decreased by amount.

Post (failure): raises InsufficientFunds; account.balance unchanged.

"""

...

These comments are not formal proofs, but they give reviewers something precise to check against.

A lightweight checklist for risky code

Be extra explicit when reviewing code that handles:

- Parsing/validation (malformed input paths, boundary cases)

- Concurrency (locks, races, idempotency, retries)

- Money/quotas (rounding, double-charging, overflow)

- Permissions (who can do what, and why)

If the change touches any of these, ask: “What are the preconditions, and where are they enforced?” and “What guarantees do we provide even when something fails?”

When to use formal tools—and a practical checklist

Formal reasoning doesn’t have to mean turning your whole codebase into a math paper. The goal is to spend extra certainty where it pays off: places where “looks fine in tests” isn’t enough.

Where formal methods help most

They’re a strong fit when you have a small, critical module that everything else depends on (auth, payment rules, permissions, safety interlocks), or a tricky algorithm where off-by-one mistakes hide for months (parsers, schedulers, caching/eviction, concurrency primitives, partition-style code, boundary-heavy data transformations).

A useful rule: if a bug can cause real harm, large financial loss, or silent data corruption, you want more than ordinary review + tests.

Tools to consider (high level)

You can choose from “lightweight” to “heavyweight,” and often the best results come from combining them:

- Types (including stronger type systems, non-null, units/quantities): prevent whole categories of invalid states.

- Static analysis: finds suspicious paths, misuse of APIs, data races, tainted input flows.

- Contracts (preconditions/postconditions, assertions): executable versions of the Hoare-style statements you reason about.

- Model checking: explores state machines (often great for protocols, concurrency, and “what if” sequences).

- Formal verification: machine-checked proofs for the highest assurance parts.

How deep should you go?

Decide the depth of formality by weighing:

- Risk: impact × likelihood. Higher risk justifies stronger guarantees.

- Cost: time to specify, prove, and maintain.

- Change rate: fast-changing code is harder to keep formally “locked down”; stabilize interfaces first.

- Team skills: start with contracts and static analysis if proofs would slow delivery too much.

In practice, you can also treat “formality” as something you incrementally add: start with explicit contracts and invariants, then let automation keep you honest. For teams building quickly on Koder.ai—where generating a React front end, a Go backend, and Postgres schema can happen in a tight loop—snapshots/rollback and source code export make it easier to iterate fast while still enforcing contracts via tests and static analysis in your usual CI.

A practical checklist

Use this as a quick “should we formalize more?” gate in planning or code review:

- What is the worst credible failure, and who gets hurt (users, ops, regulators)?

- Can tests realistically cover the important edge cases and states?

- Is the logic stateful, concurrent, or heavy on invariants/boundaries?

- Can we write clear preconditions/postconditions for the public entry points?

- Do we have a small core we can isolate and verify more deeply?

- Which tool gives the best return here: stronger types, static analysis, contracts, model checking, or proof?

- What will change next quarter, and how will we keep guarantees from drifting?

Further reading topics: design-by-contract, property-based testing, model checking for state machines, static analyzers for your language, and introductory material on proof assistants and formal specification.

FAQ

What does “correctness” mean beyond “it worked when I tried it”?

Correctness means the program satisfies an agreed specification: for every allowed input and relevant system state, it produces the required outputs and side effects (and handles errors as promised). “It seems to work” usually means you only checked a few examples, not the whole input space or the tricky boundary conditions.

What’s the difference between requirements, a specification, and an implementation?

Requirements are the business goal (“sort the list for display”). A specification is the precise, checkable promise (“returns a new list sorted ascending, same multiset of elements, input unchanged”). The implementation is the code. Bugs often happen when teams jump straight from requirements to implementation and never write down the checkable promise.

What is partial correctness vs. total correctness, and why should I care?

Partial correctness: if the code returns, the result is correct. Total correctness: the code returns and the result is correct—so termination is part of the claim.

In practice, total correctness matters whenever “hanging forever” is a user-visible failure, a resource leak, or a safety risk.

What is a Hoare triple, in plain language?

A Hoare triple {P} C {Q} reads like a contract:

P(precondition): what must be true before runningCC: the code fragment

How do I choose good preconditions for a function?

Preconditions are what the code needs (e.g., “indices are in range”, “elements are comparable”, “lock is held”). If a precondition can be violated by callers, either:

- enforce it (validation, checks, early returns), or

- make it explicit (docs/contract comments), or

- redesign the API so invalid states are harder to represent.

Otherwise, your postconditions become wishful thinking.

What is a loop invariant, and what are examples I can reuse?

A loop invariant is a statement that is true before the loop starts, stays true after every iteration, and is still true when the loop ends. Useful templates include:

- index/bounds safety (e.g.,

0 <= i <= n) - processed vs. unprocessed partitioning (what’s “done” right now)

- sorted/partitioned prefix claims

If you can’t articulate an invariant, it’s a sign the loop is doing too many things at once or the boundaries are unclear.

How do you argue that a loop or recursion will terminate?

You typically name a measure (variant) that decreases each iteration and can’t decrease forever, such as:

n - ishrinking by 1- “number of unprocessed items” decreasing

- distance between two pointers shrinking

If you can’t find a decreasing measure, you may have discovered a real non-termination risk (especially with duplicates or stalled pointers).

Why is the partition step the “heart” of Quicksort correctness?

In Quicksort, partition is the small routine everything depends on. If partition is slightly wrong, you can get:

- incorrect ordering (mis-sorted output)

- non-shrinking subranges (infinite recursion)

- out-of-bounds access (crashes)

That’s why it helps to state partition’s contract explicitly: what must be true on the left side, on the right side, and that elements are only rearranged (a permutation).

How can duplicates break a Quicksort implementation, and how do you prevent it?

Duplicates and “equal to pivot” handling are common failure points. Practical rules:

- pick one partition scheme (Hoare, Lomuto, three-way) and follow its comparisons consistently

- ensure pointers always make progress on equals (avoid stalled

i/j) - ensure recursive calls shrink (don’t keep recursing on the same range)

If duplicates are frequent, consider three-way partitioning to reduce both bugs and recursion depth.

How do “proof-style” reasoning and testing work together in real teams?

Testing samples behaviors; reasoning can rule out whole classes of bugs (bounds safety, preservation of invariants, termination). A practical hybrid workflow is:

- write a small spec (pre/postconditions, key invariants)

- reason about the tricky parts (loops, partition, recursion boundaries)

- turn the spec into tests, especially property-based tests

For sorting, two high-value properties are: