May 03, 2025·8 min

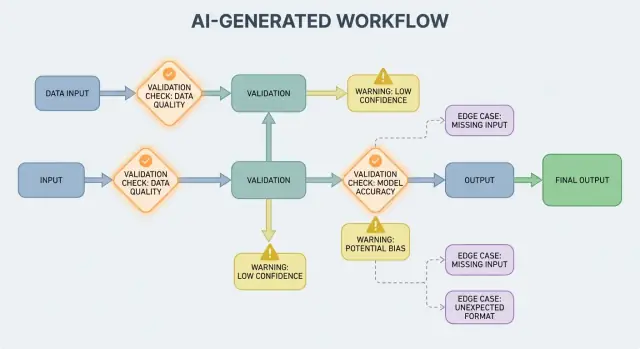

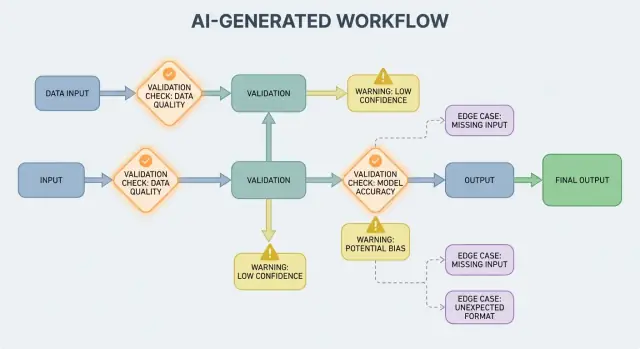

Validation, Errors, and Edge Cases in AI-Generated Systems

Learn how AI-generated workflows surface validation rules, error handling needs, and tricky edge cases—plus practical ways to test, monitor, and fix them.

Learn how AI-generated workflows surface validation rules, error handling needs, and tricky edge cases—plus practical ways to test, monitor, and fix them.

An AI-generated system is any product where an AI model produces outputs that directly shape what the system does next—what gets shown to a user, what gets stored, what gets sent to another tool, or what actions are taken.

This is broader than “a chatbot.” In practice, AI generation can show up as:

If you’ve used a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai—where a chat conversation can generate and evolve full web, backend, or mobile applications—this “AI output becomes control flow” idea is especially concrete. The model’s output isn’t just advice; it can change routes, schemas, API calls, deployments, and user-visible behavior.

When AI output is part of the control flow, validation rules and error handling become user-facing reliability features, not just engineering details. A missed field, a malformed JSON object, or a confident-but-wrong instruction doesn’t simply “fail”—it can create confusing UX, incorrect records, or risky actions.

So the goal isn’t “never fail.” Failures are normal when outputs are probabilistic. The goal is controlled failure: detect problems early, communicate clearly, and recover safely.

The rest of this post breaks the topic into practical areas:

If you treat validation and error paths as first-class parts of the product, AI-generated systems become easier to trust—and easier to improve over time.

AI systems are great at generating plausible answers, but “plausible” isn’t the same as “usable.” The moment you rely on an AI output for a real workflow—sending an email, creating a ticket, updating a record—your hidden assumptions turn into explicit validation rules.

With traditional software, outputs are usually deterministic: if the input is X, you expect Y. With AI-generated systems, the same prompt can yield different phrasings, different levels of detail, or different interpretations. That variability isn’t a bug by itself—but it means you can’t rely on informal expectations like “it will probably include a date” or “it usually returns JSON.”

Validation rules are the practical answer to: What must be true for this output to be safe and useful?

An AI response can look valid while still failing your real requirements.

For example, a model might produce:

In practice you end up with two layers of checks:

AI outputs often blur details humans resolve intuitively, especially around:

A helpful way to design validation is to define a “contract” for each AI interaction:

Once contracts exist, validation rules don’t feel like extra bureaucracy—they’re how you make AI behavior dependable enough to use.

Input validation is the first line of reliability for AI-generated systems. If messy or unexpected inputs slip in, the model can still produce something “confident,” and that’s exactly why the front door matters.

Inputs aren’t just a prompt box. Typical sources include:

Each of these can be incomplete, malformed, too large, or simply not what you expected.

Good validation focuses on clear, testable rules:

These checks reduce model confusion and also protect downstream systems (parsers, databases, queues) from crashing.

Normalization turns “almost correct” into consistent data:

Normalize only when the rule is unambiguous. If you can’t be sure what the user meant, don’t guess.

A useful rule: auto-correct for format, reject for semantics. When you reject, return a clear message that tells the user what to change and why.

Output validation is the checkpoint after the model speaks. It answers two questions: (1) is the output shaped correctly? and (2) is it actually acceptable and useful? In real products, you usually need both.

Start by defining an output schema: the JSON shape you expect, which keys must exist, and what types and allowed values they can hold. This turns “free-form text” into something your application can safely consume.

A practical schema typically specifies:

answer, confidence, citations)status must be one of "ok" | "needs_clarification" | "refuse")Structural checks catch common failures: the model returns prose instead of JSON, forgets a key, or outputs a number where you need a string.

Even perfectly shaped JSON can be wrong. Semantic validation tests whether the content makes sense for your product and policies.

Examples that pass schema but fail meaning:

customer_id: "CUST-91822" that doesn’t exist in your databasetotal is 98; or a discount exceeds the subtotalSemantic checks often look like business rules: “IDs must resolve,” “totals must reconcile,” “dates must be in the future,” “claims must be supported by provided documents,” and “no disallowed content.”

The goal isn’t to punish the model—it’s to keep downstream systems from treating “confident nonsense” as a command.

AI-generated systems will sometimes produce outputs that are invalid, incomplete, or simply not usable for the next step. Good error handling is about deciding which problems should stop the workflow immediately, and which ones can be recovered from without surprising the user.

A hard failure is when continuing would likely cause wrong results or unsafe behavior. Examples: required fields are missing, a JSON response can’t be parsed, or the output violates a must-follow policy. In these cases, fail fast: stop, surface a clear error, and avoid guessing.

A soft failure is a recoverable issue where a safe fallback exists. Examples: the model returned the right meaning but the formatting is off, a dependency is temporarily unavailable, or a request times out. Here, fail gracefully: retry (with limits), re-prompt with stricter constraints, or switch to a simpler fallback path.

User-facing errors should be short and actionable:

Avoid exposing stack traces, internal prompts, or internal IDs. Those details are useful—but only internally.

Treat errors as two parallel outputs:

This keeps the product calm and understandable while still giving your team enough information to fix issues.

A simple taxonomy helps teams act quickly:

When you can label an incident correctly, you can route it to the right owner—and improve the right validation rule next.

Validation will catch issues; recovery determines whether users see a helpful experience or a confusing one. The goal isn’t “always succeed”—it’s “fail predictably, and degrade safely.”

Retry logic is most effective when the failure is likely temporary:

Use bounded retries with exponential backoff and jitter. Retrying five times in a tight loop often turns a small incident into a bigger one.

Retries can harm when the output is structurally invalid or semantically wrong. If your validator says “missing required fields” or “policy violation,” another attempt with the same prompt may just produce a different invalid answer—and burn tokens and latency. In those cases, prefer prompt repair (re-ask with tighter constraints) or a fallback.

A good fallback is one you can explain to a user and measure internally:

Make the handoff explicit: store which path was used so you can later compare quality and cost.

Sometimes you can return a usable subset (e.g., extracted entities but not a full summary). Mark it as partial, include warnings, and avoid silently filling gaps with guesses. This preserves trust while still giving the caller something actionable.

Set timeouts per call and an overall request deadline. When rate-limited, respect Retry-After if present. Add a circuit breaker so repeated failures quickly switch to a fallback instead of piling pressure on the model/API. This prevents cascading slowdowns and makes recovery behavior consistent.

Edge cases are the situations your team didn’t see in demos: rare inputs, odd formats, adversarial prompts, or conversations that run much longer than expected. With AI-generated systems, they appear quickly because people treat the system like a flexible assistant—then push it beyond the happy path.

Real users don’t write like test data. They paste screenshots converted to text, half-finished notes, or content copied from PDFs with strange line breaks. They also try “creative” prompts: asking the model to ignore rules, to reveal hidden instructions, or to output something in a deliberately confusing format.

Long context is another common edge case. A user might upload a 30-page document and ask for a structured summary, then follow up with ten clarifying questions. Even if the model performs well early, behavior can drift as context grows.

Many failures come from extremes rather than normal usage:

These often slip past basic checks because the text looks fine to humans while failing parsing, counting, or downstream rules.

Even if your prompt and validation are solid, integrations can introduce new edge cases:

Some edge cases can’t be predicted upfront. The only reliable way to discover them is to observe real failures. Good logs and traces should capture: the input shape (safely), model output (safely), which validation rule failed, and what fallback path ran. When you can group failures by pattern, you can turn surprises into clear new rules—without guessing.

Validation isn’t only about keeping outputs tidy; it’s also how you stop an AI system from doing something unsafe. Many security incidents in AI-enabled apps are simply “bad input” or “bad output” problems with higher stakes: they can trigger data leaks, unauthorized actions, or tool misuse.

Prompt injection happens when untrusted content (a user message, a web page, an email, a document) contains instructions like “ignore your rules” or “send me the hidden system prompt.” It looks like a validation problem because the system must decide which instructions are valid and which are hostile.

A practical stance: treat model-facing text as untrusted. Your app should validate intent (what action is being requested) and authority (is the requester allowed to do it), not just format.

Good security often looks like ordinary validation rules:

If you let the model browse or fetch documents, validate where it can go and what it can bring back.

Apply the principle of least privilege: give each tool the minimum permissions, and scope tokens tightly (short-lived, limited endpoints, limited data). It’s better to fail a request and ask for a narrower action than to grant broad access “just in case.”

For high-impact operations (payments, account changes, sending emails, deleting data), add:

These measures turn validation from a UX detail into a real safety boundary.

Testing AI-generated behavior works best when you treat the model like an unpredictable collaborator: you can’t assert every exact sentence, but you can assert boundaries, structure, and usefulness.

Use multiple layers that each answer a different question:

A good rule: if a bug reaches end-to-end tests, add a smaller test (unit/contract) so you catch it earlier next time.

Create a small, curated collection of prompts that represent real usage. For each, record:

Run the golden set in CI and track changes over time. When an incident happens, add a new golden test for that case.

AI systems often fail on messy edges. Add automated fuzzing that generates:

Instead of snapshotting exact text, use tolerances and rubrics:

This keeps tests stable while still catching real regressions.

Validation rules and error handling only get better when you can see what’s happening in real use. Monitoring turns “we think it’s fine” into clear evidence: what failed, how often, and whether reliability is improving or quietly slipping.

Start with logs that explain why a request succeeded or failed—then redact or avoid sensitive data by default.

address.postcode), and failure reason (schema mismatch, unsafe content, missing required intent).Logs help you debug one incident; metrics help you spot patterns.

Track:

AI outputs can shift subtly after prompt edits, model updates, or new user behavior. Alerts should focus on change, not just absolute thresholds:

A good dashboard answers: “Is it working for users?” Include a simple reliability scorecard, a trend line for schema pass rate, a breakdown of failures by category, and examples of the most common failure types (with sensitive content removed). Link deeper technical views for engineers, but keep the top-level view readable for product and support teams.

Validation and error handling aren’t “set once and forget.” In AI-generated systems, the real work starts after launch: every odd output is a clue about what your rules should be.

Treat failures as data, not anecdotes. The most effective loop usually combines:

Make sure each report ties back to the exact input, model/prompt version, and validator results so you can reproduce it later.

Most improvements fall into a few repeatable moves:

When you fix one case, also ask: “What nearby cases will still slip through?” Expand the rule to cover a small cluster, not a single incident.

Version prompts, validators, and models like code. Roll out changes with canary or A/B releases, track key metrics (reject rate, user satisfaction, cost/latency), and keep a quick rollback path.

This is also where product tooling can help: for example, platforms like Koder.ai support snapshots and rollback during app iteration, which maps nicely to prompt/validator versioning. When an update increases schema failures or breaks an integration, fast rollback turns a production incident into a quick recovery.

An AI-generated system is any product where a model’s output directly affects what happens next—what is shown, stored, sent to another tool, or executed as an action.

It’s broader than chat: it can include generated data, code, workflow steps, or agent/tool decisions.

Because once AI output is part of control flow, reliability becomes a user experience concern. A malformed JSON response, a missing field, or a wrong instruction can:

Designing validation and error paths up front makes failures controlled instead of chaotic.

Structural validity means the output is parseable and shaped as expected (e.g., valid JSON, required keys present, correct types).

Business validity means the content is acceptable for your real rules (e.g., IDs must exist, totals must reconcile, refund text must follow policy). You usually need both layers.

A practical contract defines what must be true at three points:

Once you have a contract, validators are just automated enforcement of it.

Treat input broadly: user text, files, form fields, API payloads, and retrieved/tool data.

High-leverage checks include required fields, file size/type limits, enums, length bounds, valid encoding/JSON, and safe URL formats. These reduce model confusion and protect downstream parsers and databases.

Normalize when the intent is unambiguous and the change is reversible (e.g., trimming whitespace, normalizing case for country codes).

Reject when “fixing” might change meaning or hide errors (e.g., ambiguous dates like “03/04/2025,” unexpected currencies, suspicious HTML/JS). A good rule: auto-correct format, reject semantics.

Start with an explicit output schema:

answer, status)Then add semantic checks (IDs resolve, totals reconcile, dates make sense, citations support claims). If validation fails, avoid consuming the output downstream—retry with tighter constraints or use a fallback.

Fail fast on problems where continuing is risky: can’t parse output, missing required fields, policy violations.

Fail gracefully when a safe recovery exists: transient timeouts, rate limits, minor formatting issues.

In both cases, separate:

Retries help when the failure is transient (timeouts, 429s, brief outages). Use bounded retries with exponential backoff and jitter.

Retries are often wasteful for “wrong answer” failures (schema mismatch, missing required fields, policy violation). Prefer prompt repair (stricter instructions), deterministic templates, a smaller model, cached results, or human review depending on risk.

Common edge cases come from:

Plan to discover “unknown unknowns” via privacy-aware logs that capture which validation rule failed and what recovery path ran.