Sep 01, 2025·8 min

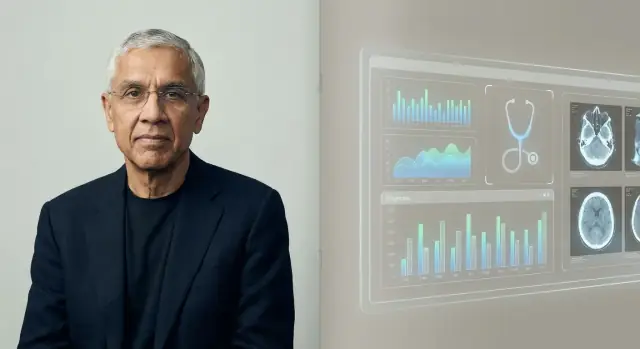

Vinod Khosla and the Bet That AI Will Replace Doctors

Why Vinod Khosla argued AI could replace many doctors—his reasoning, the healthcare bets behind it, what AI can and can’t do, and what it means for patients.

Why Vinod Khosla argued AI could replace many doctors—his reasoning, the healthcare bets behind it, what AI can and can’t do, and what it means for patients.

When Vinod Khosla says “AI will replace doctors,” he’s usually not describing a sci‑fi hospital with no humans. He’s making a sharper, operational claim: many tasks that currently consume a physician’s time—especially information-heavy work—can be done by software that is faster, cheaper, and increasingly accurate.

In Khosla’s framing, “replace” often means substitute for a large share of what doctors do day to day, not erase the profession. Think of the repetitive parts of care: gathering symptoms, checking guidelines, ranking likely diagnoses, recommending next tests, monitoring chronic conditions, and flagging risk early.

That’s why the idea is more “pro‑automation” than “anti‑doctor.” The underlying bet is that healthcare is full of patterns—and pattern recognition at scale is where AI tends to excel.

This piece treats the statement as a hypothesis to evaluate, not a slogan to cheer or dismiss. We’ll look at the reasoning behind it, the kinds of healthcare products that align with it, and the real constraints: regulation, safety, liability, and the human side of medicine.

Vinod Khosla is a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and investor best known for co-founding Sun Microsystems in the 1980s and later building a long career in venture capital. After time at Kleiner Perkins, he founded Khosla Ventures in 2004.

That mix—operator experience plus decades of investing—helps explain why his claims about AI and healthcare get repeated far beyond tech circles.

Khosla Ventures has a reputation for backing big, high-conviction bets that can look unreasonable at first. The firm often leans into:

This matters because predictions like “AI will replace doctors” aren’t just rhetoric—they can shape what startups get funded, what products get built, and what narratives boards and executives take seriously.

Healthcare is one of the largest, most expensive parts of the economy, and it’s also filled with signals AI can potentially learn from: images, lab results, notes, sensor data, and outcomes. Even modest improvements in accuracy, speed, or cost can translate into meaningful savings and access gains.

Khosla and his firm have repeatedly argued that medicine is ripe for software-driven change—especially in areas like triage, diagnosis support, and workflow automation. Whether or not you agree with the “replacement” framing, his view matters because it reflects how a major slice of venture capital evaluates the future of medicine—and where money will flow next.

Khosla’s prediction rests on a simple claim: a large share of medicine—especially primary care and early triage—is pattern recognition under uncertainty. If diagnosis and treatment selection are, in many cases, “match this presentation to what’s most likely,” then software that can learn from millions of examples should eventually outperform individual clinicians who learn from thousands.

Humans are excellent at spotting patterns, but we’re limited by memory, attention, and experience. An AI system can ingest far more cases, guidelines, and outcomes than any one doctor can encounter in a career, then apply that learned pattern-matching consistently. In Khosla’s framing, once the system’s error rate drops below the average clinician’s, the rational choice for patients and payers is to route routine decisions through the machine.

Economics is the other forcing function. Primary care is constrained by time, geography, and staffing shortages; visits can be expensive, brief, and variable in quality. An AI service can be available 24/7, scale to underserved areas, and deliver more uniform decision-making—reducing the “it depends who you saw” problem.

Earlier expert systems struggled because they relied on hand-coded rules and narrow datasets. Feasibility improved as medical data digitized (EHRs, imaging, labs, wearables) and computing made it practical to train models on massive corpora and update them continuously.

Even in this logic, the “replacement” line is usually drawn around routine diagnosis and protocol-driven management—not the parts of medicine centered on trust, complex tradeoffs, and supporting patients through fear, ambiguity, or life-changing decisions.

Khosla’s “AI will replace doctors” line is typically delivered as a provocative forecast, not a literal promise that hospitals will become doctor-free. The repeated theme across his talks and interviews is that much of medicine—especially diagnosis and routine treatment decisions—follows patterns that software can learn, measure, and improve.

He often frames clinical reasoning as a form of pattern matching across symptoms, histories, images, labs, and outcomes. The core claim is that once an AI model reaches a certain quality bar, it can be deployed widely and updated continuously—while clinician training is slow, expensive, and uneven across regions.

A key nuance in his framing is variability: clinicians can be excellent but inconsistent due to fatigue, workload, or limited exposure to rare cases. AI, by contrast, can offer steadier performance and potentially lower error rates when it’s tested, monitored, and retrained properly.

Rather than imagining AI as a single decisive “doctor replacement,” his strongest version reads more like: most patients will consult an AI first, and human clinicians will increasingly act as reviewers for complex cases, edge conditions, and high-stakes decisions.

Supporters interpret his stance as a push toward measurable outcomes and access. Critics note that real-world medicine includes ambiguity, ethics, and accountability—and that “replacement” depends as much on regulation, workflow, and trust as on model accuracy.

Khosla’s “AI will replace doctors” claim maps neatly onto the kinds of healthcare startups VCs like to fund: companies that can scale fast, standardize messy clinical work, and turn expert judgment into software.

A lot of the bets that align with this thesis cluster into a few repeatable themes:

Replacing (or shrinking) the need for clinicians is a huge prize: healthcare spend is massive, and labor is a major cost center. That creates incentives to frame timelines boldly—because fundraising rewards a clear, high-upside story, even when clinical adoption and regulation move slower than software.

A point solution does one job well (e.g., read chest X-rays). A platform aims to sit across many workflows—triage, diagnosis support, follow-up, billing—using shared data pipelines and models.

The “replace doctors” narrative depends more on platforms: if AI only wins in one narrow task, doctors adapt; if it coordinates many tasks end-to-end, the clinician’s role can shift toward oversight, exceptions, and accountability.

For founders exploring these “platform” ideas, speed matters early: you often need working prototypes of intake flows, clinician dashboards, and audit trails before you can even test a workflow. Tools like Koder.ai can help teams build internal web apps (commonly React on the front end, Go + PostgreSQL on the back end) from a chat interface, then export source code and iterate quickly. For anything that touches clinical decisions, you’d still need proper validation, security review, and regulatory strategy—but rapid prototyping can shorten the path to a realistic pilot.

AI already outperforms humans in specific, narrow slices of clinical work—especially when the job is mostly about pattern recognition, speed, and consistency. That doesn’t mean “AI doctor” in the full sense. It means AI can be a very strong component of care.

AI tends to shine where there’s a lot of repetitive information and clear feedback loops:

In these areas, “better” often means fewer missed findings, more standardized decisions, and faster turnaround.

Most real-world wins today come from clinical decision support (CDS): AI suggests likely conditions, flags dangerous alternatives, recommends next tests, or checks guideline adherence—while a clinician remains accountable.

Autonomous diagnosis (AI making the call end-to-end) is feasible in limited, well-defined contexts—like screening workflows with strict protocols—but it’s not the default for complex, multi-morbidity patients.

AI’s accuracy depends heavily on training data that matches the patient population and care setting. Models can drift when:

In high-stakes settings, oversight isn’t optional—it’s the safety layer for edge cases, unusual presentations, and value-based judgment (what a patient is willing to do, tolerate, or prioritize). AI can be excellent at seeing, but clinicians still have to decide what that means for this person, today.

AI can be impressive at pattern-matching, summarizing records, and suggesting likely diagnoses. But medicine isn’t only a prediction task. Many of the hardest parts happen when the “right” answer is unclear, the patient’s goals conflict with guidelines, or the system around care is messy.

People don’t just want a result—they want to feel heard, believed, and safe. A clinician can notice fear, shame, confusion, or domestic risk, then adjust the conversation and plan accordingly. Shared decision-making also requires negotiating tradeoffs (side effects, cost, lifestyle, family support) in a way that builds trust over time.

Real patients often have several conditions at once, incomplete histories, and symptoms that don’t fit a clean template. Rare diseases and atypical presentations can look like common problems—until they don’t. AI may generate plausible suggestions, but “plausible” isn’t the same as “clinically proven,” especially when subtle context matters (recent travel, new meds, social factors, “something feels off”).

Even a highly accurate model will sometimes fail. The hard question is who carries responsibility: the clinician who followed the tool, the hospital that deployed it, or the vendor that built it? Clear accountability affects how cautious teams must be—and how patients can seek recourse.

Care happens inside workflows. If an AI tool can’t integrate cleanly with EHRs, ordering systems, documentation, and billing—or if it adds clicks and uncertainty—busy teams won’t rely on it, no matter how good the demo looks.

Medical AI isn’t just an engineering problem—it’s a safety problem. When software influences diagnosis or treatment, regulators treat it more like a medical device than a typical app.

In the U.S., the FDA regulates many “Software as a Medical Device” tools, especially those that diagnose, recommend treatment, or directly affect care decisions. In the EU, CE marking under the Medical Device Regulation serves a similar role.

These frameworks require evidence that the tool is safe and effective, clarity about intended use, and ongoing monitoring once it’s deployed. The rules matter because a model that looks impressive in a demo can still fail in real clinics, with real patients.

A major ethical risk is uneven accuracy across populations (for example, different age groups, skin tones, languages, or comorbidities). If training data underrepresents certain groups, the system can systematically miss diagnoses or over-recommend interventions for them. Fairness testing, subgroup reporting, and careful dataset design aren’t optional add-ons—they’re part of basic safety.

Training and improving models often requires large amounts of sensitive health data. That raises questions about consent, secondary use, de-identification limits, and who benefits financially. Good governance includes clear patient notices, strict access controls, and policies for data retention and model updates.

Many clinical AI tools are designed to assist, not replace, by keeping a clinician responsible for the final decision. This “human-in-the-loop” approach can catch errors, provide context the model lacks, and create accountability—though it only works if workflows and incentives prevent blind automation.

Khosla’s claim is often heard as “doctors will be obsolete.” A more useful reading is to separate replacement (the AI performs a task end-to-end with minimal human input) from reallocation (humans still own outcomes, but the work shifts toward oversight, empathy, and coordination).

In many settings, AI is likely to replace pieces of clinical work first: drafting notes, surfacing differential diagnoses, checking guideline adherence, and summarizing patient history. The clinician’s job shifts from generating answers to auditing, contextualizing, and communicating them.

Primary care may feel the change as “front door” triage improves: symptom checkers and ambient documentation reduce routine visit time, while complex cases and relationship-based care remain human-led.

Radiology and pathology could see more direct task replacement because the work is already digital and pattern-based. That doesn’t mean fewer specialists overnight—it more likely means higher throughput, new quality workflows, and pressure on reimbursement.

Nursing is less about diagnosis and more about continuous assessment, education, and coordination. AI may reduce clerical burden, but bedside care and escalation decisions stay people-centered.

Expect growth in roles like AI supervisor (monitoring model performance), clinical informatics (workflow + data stewardship), and care coordinator (closing gaps the model flags). These roles may sit inside existing teams rather than being separate titles.

Medical education may add AI literacy: how to validate outputs, document reliance, and spot failure modes. Credentialing could evolve toward “human-in-the-loop” standards—who is allowed to use which tools, under what supervision, and how accountability is assigned when AI is wrong.

Khosla’s claim is provocative because it treats “doctor” as mostly a diagnostic engine. The strongest pushback argues that even if AI matches clinicians on pattern recognition, replacing doctors is a different job entirely.

A large share of clinical value sits in framing the problem, not just answering it. Doctors translate messy stories into workable options, negotiate trade-offs (risk, cost, time, values), and coordinate care across specialists. They also handle consent, uncertainty, and “watchful waiting”—areas where trust and accountability matter as much as accuracy.

Many AI systems look impressive in retrospective studies, but that’s not the same as improving real-world outcomes. The hardest proof is prospective evidence: does AI reduce missed diagnoses, complications, or unnecessary testing across different hospitals, patient groups, and workflows?

Generalization is another weak spot. Models can degrade when the population changes, when equipment differs, or when documentation habits shift. A system that performs well at one site may stumble elsewhere—especially for rarer conditions.

Even strong tools can create new failure modes. Clinicians may defer to the model when it’s wrong (automation bias) or stop asking the second question that catches edge cases. Over time, skills can atrophy if humans become “rubber stamps,” making it harder to intervene when the AI is uncertain or incorrect.

Healthcare isn’t a pure technology market. Liability, reimbursement, procurement cycles, integration with EHRs, and clinician training all slow deployment. Patients and regulators may also demand a human decision-maker for high-stakes calls—meaning “AI everywhere” could still look like “AI supervised by doctors” for a long time.

AI is already showing up in healthcare in quiet ways—risk scores in your chart, automated reads of scans, symptom checkers, and tools that prioritize who gets seen first. For patients, the goal isn’t to “trust AI” or “reject AI,” but to know what to expect and how to stay in control.

You’ll likely see more screening (messages, questionnaires, wearable data) and faster triage—especially in busy clinics and ERs. That can mean quicker answers for common issues and earlier detection for some conditions.

Quality will be mixed. Some tools are excellent in narrow tasks; others can be inconsistent across age groups, skin tones, rare diseases, or messy real-world data. Treat AI as a helper, not a final verdict.

If an AI tool influences your care, ask:

Many AI outputs are probabilities (“20% risk”) rather than certainties. Ask what the number means for you: what happens at different risk levels, and what the false-alarm rate is.

If the recommendation is high-stakes (surgery, chemo, stopping a medication), request a second opinion—human and/or a different tool. It’s reasonable to ask, “What would you do if this AI result didn’t exist?”

You should be told when software meaningfully shapes decisions. If you’re uncomfortable, ask about alternatives, how your data is stored, and whether opting out affects access to care.

AI in healthcare is easiest to adopt when you treat it like any other clinical tool: define the use case, test it, monitor it, and make accountability obvious.

Before you use AI for diagnosis, use it to remove everyday friction. The safest early wins are workflows that improve throughput without making medical decisions:

These areas often deliver measurable time savings, and they help teams build confidence in change management.

If your team needs lightweight internal tools to support these workflows—intake forms, routing dashboards, audit logs, staff-facing knowledge bases—rapid app-building can be as valuable as model quality. Platforms like Koder.ai are designed for “vibe-coding” teams: you describe the app in chat, iterate quickly, and export the source code when you’re ready to harden it for production. For clinical contexts, treat this as a way to accelerate operations software and pilots, while still doing the required security, compliance, and validation work.

For any AI system that touches patient care—even indirectly—require evidence and operational controls:

If a vendor can’t explain how the model was evaluated, updated, and audited, treat that as a safety signal.

Make “how we use this” as clear as “what it does.” Provide clinician training that includes common failure modes, and establish explicit escalation paths (when to ignore the AI, when to ask a colleague, when to refer, when to send to ED). Assign an owner for performance reviews and incident reporting.

If you want help selecting, piloting, or governing tools, add an internal path for stakeholders to request support via /contact (or /pricing if you package deployment services).

Predictions about AI “replacing doctors” tend to fail when they treat medicine like a single job with a single finish line. A more realistic view is that change will arrive unevenly—by specialty, setting, and task—and will be pulled forward when incentives and rules finally align.

In the near term, the biggest gains are likely to be “workflow wins”: better triage, clearer documentation, faster prior authorizations, and decision support that reduces obvious errors. These can expand access without forcing patients to trust a machine alone.

Over the longer run, you’ll see gradual shifts in who does what—especially in standardized, high-volume care where data is plentiful and outcomes are measurable.

Replacement rarely means doctors vanish. It may look like:

The balanced take: progress will be real and sometimes startling, but medicine isn’t only pattern recognition. Trust, context, and patient-centered care will keep humans central—even as the toolset changes.

Khosla typically means AI will replace a large share of day-to-day clinical tasks, especially information-heavy work like triage, guideline checking, ranking likely diagnoses, and monitoring chronic conditions.

It’s less “no humans in hospitals” and more “software becomes the default first pass for routine decisions.”

In this article’s terms:

Most near-term real-world deployments look like augmentation, with replacement limited to narrow, well-defined workflows.

The core logic is pattern recognition at scale: many clinical judgments (especially early triage and routine diagnosis) resemble matching symptoms, histories, labs, and images to likely conditions.

AI can train on far more cases than a single clinician sees and apply that learning consistently, potentially lowering average error rates over time.

VCs pay attention because Khosla’s view can influence:

Even if you disagree with the framing, it can shape capital flows and adoption priorities.

Healthcare is expensive and labor-intensive, and it produces lots of data (EHR notes, labs, imaging, sensor data). That combination makes it attractive for AI bets where even small improvements can yield big savings.

It’s also an area with access problems (shortages, geography), where 24/7 software services can look compelling.

AI is strongest where the work is repetitive and measurable, such as:

These are “component” wins that can meaningfully reduce clinician workload without fully automating care.

Key limitations highlighted include:

High accuracy in a demo doesn’t automatically translate into safe, reliable performance in clinics.

Many tools that influence diagnosis or treatment are regulated as Software as a Medical Device:

Ongoing monitoring matters because models can drift when populations, equipment, or documentation patterns change.

Bias happens when training data underrepresents certain groups or care settings, leading to uneven performance across age, skin tone, language, comorbidities, or geography.

Practical mitigations include subgroup validation, reporting performance by population, and monitoring post-deployment drift—not treating fairness as a one-time checkbox.

Start with patient-centered transparency and control:

A useful question is: “What would you do if this AI result didn’t exist?”