Nov 04, 2025·8 min

Vint Cerf, TCP/IP, and the Choices That Built the Internet

Explore how Vint Cerf’s TCP/IP decisions enabled interoperable networks and later global software platforms—from email and the web to cloud apps.

Why Protocol Decisions Matter for Global Platforms

Most people experience the Internet through products: a website that loads instantly, a video call that (mostly) works, a payment that clears in seconds. Underneath those experiences are protocols—shared rules that let different systems exchange messages reliably enough to be useful.

A protocol is like agreeing on a common language and etiquette for communication: what a message looks like, how you start and end a conversation, what you do when something is missing, and how you know who a message is for. Without shared rules, every connection becomes a one-off negotiation, and networks don’t scale beyond small circles.

Vint Cerf is often credited as a “father of the Internet,” but it’s more accurate (and more useful) to see his role as part of a team that made pragmatic design choices—especially around TCP/IP—that turned “networks” into an internetwork. Those choices weren’t inevitable. They reflected trade-offs: simplicity vs. features, flexibility vs. control, and speed of adoption vs. perfect guarantees.

Why platform teams should care

Today’s global platforms—web apps, mobile services, cloud infrastructure, and APIs between businesses—still live or die by the same idea: if you standardize the right boundaries, you can let millions of independent actors build on top without asking permission. Your phone can talk to servers across continents not just because hardware got faster, but because the rules of the road stayed stable enough for innovation to pile up.

That mindset matters even when you’re “just building software.” For example, vibe-coding platforms like Koder.ai succeed when they provide a small set of stable primitives (projects, deployments, environments, integrations) while letting teams iterate quickly at the edges—whether they’re generating a React frontend, a Go + PostgreSQL backend, or a Flutter mobile app.

What you’ll get from this article

We’ll touch the history briefly, but the focus is on design decisions and their consequences: how layering enabled growth, where “good enough” delivery unlocked new applications, and what early assumptions got wrong about congestion and security. The goal is practical: take protocol thinking—clear interfaces, interoperability, and explicit trade-offs—and apply it to modern platform design.

The Problem Before the Internet: Many Networks, No Common Glue

Before “the Internet” was a thing, there were plenty of networks—just not one network everyone could share. Universities, government labs, and companies were building their own systems to solve local needs. Each network worked, but they rarely worked together.

A quick timeline (high-level)

- Late 1960s: ARPANET proves the idea of connecting distant computers over a shared network.

- Early 1970s: New packet networks appear, built by different organizations with different rules and equipment.

- Late 1970s–early 1980s: Internetworking experiments mature into shared standards that many networks can adopt.

Why there were so many separate networks

Multiple networks existed for practical reasons, not because people enjoyed fragmentation. Operators had different goals (research, military reliability, commercial service), different budgets, and different technical constraints. Hardware vendors sold incompatible systems. Some networks were optimized for long-distance links, others for campus environments, and others for specialized services.

The result was lots of “islands” of connectivity.

The real problem: interconnection without rewrites

If you wanted two networks to talk, the brute-force option was to rebuild one side to match the other. That rarely happens in the real world: it’s expensive, slow, and politically messy.

What was needed was a common glue—a way for independent networks to interconnect while keeping their internal choices. This meant:

- allowing different networks to keep their own hardware and operating practices

- enabling messages to travel across multiple networks as a single journey

- avoiding a single owner or central control that everyone must trust

That challenge set the stage for the internetworking ideas Cerf and others would champion: connect networks at a shared layer, so innovation can happen above it and diversity can continue below it.

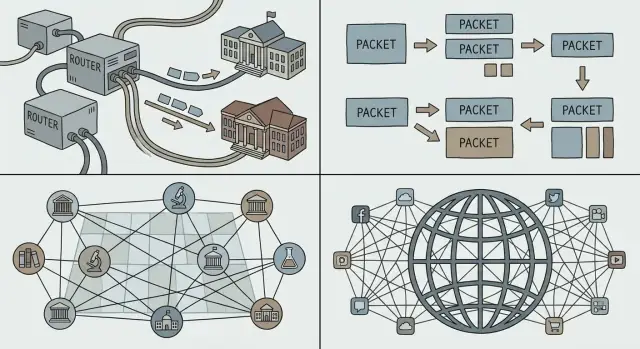

Packet Switching: The Foundation Under Everything

If you’ve ever made a phone call, you’ve experienced the intuition behind circuit switching: a dedicated “line” is effectively reserved for you end-to-end for the duration of the call. That works well for steady, real-time voice, but it’s wasteful when the conversation is mostly silence.

Packet switching flips the model. An everyday analogy is the postal service: instead of reserving a private highway from your house to a friend’s, you put your message into envelopes. Each envelope (packet) is labeled, routed through shared roads, and reassembled at the destination.

Why packets match computers (and the web)

Most computer traffic is bursty. An email, a file download, or a web page isn’t a continuous stream—it’s a quick burst of data, then nothing, then another burst. Packet switching lets many people share the same network links efficiently, because the network carries packets for whoever has something to send right now.

This is a key reason the Internet could support new applications without renegotiating how the underlying network worked: you can ship a tiny message or a huge video using the same basic method—break it into packets and send.

Scaling across distance—and across organizations

Packets also scale socially, not just technically. Different networks (run by universities, companies, or governments) can interconnect as long as they agree on how to forward packets. No single operator has to “own” the entire path; each domain can carry traffic to the next.

The trade-offs: delay, loss, and control

Because packets share links, you can get queueing delay, jitter, or even loss when networks are busy. Those downsides drove the need for control mechanisms—retransmissions, ordering, and congestion control—so packet switching stays fast and fair even under heavy load.

Internetworking and the TCP/IP Split: A Simple, Powerful Layering

The goal Cerf and colleagues were chasing wasn’t “build one network.” It was interconnect many networks—university, government, commercial—while letting each one keep its own technology, operators, and rules.

One big idea: split the job in two

TCP/IP is often described as a “suite,” but the pivotal design move is the separation of concerns:

- IP (Internet Protocol) handles addressing and routing: getting packets from one network to another, hop by hop.

- TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) handles reliable delivery (when you need it): ordering, retransmission, and flow control so applications can treat the connection like a clean pipe.

That split let the “internet” act like a common delivery fabric, while reliability became an optional service layered on top.

Why layering keeps winning

Layering makes systems easier to evolve because you can upgrade one layer without renegotiating everything above it. New physical links (fiber, Wi‑Fi, cellular), routing strategies, and security mechanisms can arrive over time—yet applications still speak TCP/IP and keep working.

It’s the same pattern platform teams rely on: stable interfaces, replaceable internals.

“Good enough primitives” create surprise applications

IP doesn’t promise perfection; it provides simple, universal primitives: “here’s a packet” and “here’s an address.” That restraint enabled unexpected applications to flourish—email, the web, streaming, real-time chat—because innovators could build what they needed at the edges without asking the network for permission.

If you’re designing a platform, this is a useful test: are you offering a few dependable building blocks, or overfitting the system to today’s favorite use case?

Best-Effort IP: Let the Network Be Simple, Let Apps Innovate

“Best-effort” delivery is a plain idea: IP will try to move your packets toward the destination, but it doesn’t promise they’ll arrive, arrive in order, or arrive on time. Packets can be dropped when links are busy, delayed by congestion, or take different routes.

Why “no guarantees” helped the Internet spread

That simplicity was a feature, not a flaw. Different organizations could connect very different networks—expensive, high-quality lines in some places; noisy, low-bandwidth links in others—without requiring everyone to upgrade to the same premium infrastructure.

Best-effort IP lowered the “entry price” to participate. Universities, governments, startups, and eventually households could join using whatever connectivity they could afford. If the core protocol had required strict guarantees from every network along the path, adoption would have stalled: the weakest link would have blocked the whole chain.

Reliability moved to the endpoints

Instead of building a perfectly reliable core, the Internet pushed reliability out to the hosts (the devices at each end). If an application needs correctness—like file transfers, payments, or loading a webpage—it can use protocols and logic at the edges to detect loss and recover:

- retransmit missing data

- reorder packets

- verify integrity and completeness

TCP is the classic example: it turns an unreliable packet service into a reliable stream by doing the hard work at the endpoints.

What platforms gained: stable building blocks worldwide

For platform teams, best-effort IP created a predictable foundation: everywhere in the world, you can assume you have the same basic service—send packets to an address, and they’ll usually get there. That consistency made it possible to build global software platforms that behave similarly across countries, carriers, and hardware.

The End-to-End Principle and Its Real-World Trade-Offs

Bring your team in

Move faster together with shared projects and repeatable deployments.

The end-to-end principle is a deceptively simple idea: keep the network “core” as minimal as possible, and put intelligence at the edges—on the devices and in the applications.

Why “smart edges” helped software move faster

For software builders, this separation was a gift. If the network didn’t need to understand your application, you could ship new ideas without negotiating changes with every network operator.

That flexibility is a big reason global platforms could iterate quickly: email, the web, voice/video calling, and later mobile apps all rode on the same underlying plumbing.

The trade-offs: abuse, security, and QoS expectations

A simple core also means the core doesn’t “protect” you by default. If the network mostly forwards packets, it’s easier for attackers and abusers to use that same openness for spam, scanning, denial-of-service attacks, and fraud.

Quality-of-service is another tension. Users expect smooth video calls and instant responses, but best-effort delivery can produce jitter, congestion, and inconsistent performance. The end-to-end approach pushes many fixes upward: retry logic, buffering, rate adaptation, and application-level prioritization.

Modern platform features built on top

A lot of what people think of as “the internet” today is extra structure layered above the minimal core: CDNs that move content closer to users, encryption (TLS) to add privacy and integrity, and streaming protocols that adapt quality to current conditions. Even “network-ish” capabilities—like bot protection, DDoS mitigation, and performance acceleration—are often delivered as platform services at the edge rather than baked into IP itself.

Addressing, Routing, and DNS: Making a Global Network Usable

A network can only become “global” when every device can be reached reliably enough, without requiring every participant to know about every other participant. That’s the job of addressing, routing, and DNS: three ideas that turn a pile of connected networks into something people (and software) can actually use.

Addressing vs. routing (the simple version)

An address is an identifier that tells the network where something is. With IP, that “where” is expressed in a structured numeric form.

Routing is the process of deciding how to move packets toward that address. Routers don’t need a full map of every machine on Earth; they only need enough information to forward traffic step by step in the right direction.

The key is that forwarding decisions can be local and fast, while the overall result still looks like global reachability.

Why hierarchy and aggregation are what make scale possible

If every individual device address had to be listed everywhere, the Internet would collapse under its own bookkeeping. Hierarchical addressing allows addresses to be grouped (for example, by network or provider), so routers can keep aggregated routes—one entry that represents many destinations.

This is the unglamorous secret behind growth: smaller routing tables, fewer updates, and simpler coordination across organizations. Aggregation is also why IP addressing policies and allocations matter to operators: they directly affect how expensive it is to keep the global system coherent.

DNS: usability for humans, flexibility for platforms

Humans don’t want to type numbers, and services don’t want to be permanently tied to a single machine. DNS (Domain Name System) is the naming layer that maps readable names (like api.example.com) to IP addresses.

For platform teams, DNS is more than convenience:

- It supports global user bases by directing users to nearby regions.

- It helps distributed services move and scale without changing client configuration.

- It enables multi-region apps and failover strategies where the name stays stable while the underlying infrastructure changes.

In other words, addressing and routing make the Internet reachable; DNS makes it usable—and operationally adaptable—at platform scale.

Open Standards and Interoperability: The Flywheel Behind Adoption

Put it on your domain

Connect a custom domain to share a clean, stable endpoint.

A protocol only becomes “the Internet” when lots of independent networks and products can use it without asking permission. One of the smartest choices around TCP/IP wasn’t just technical—it was social: publish the specs, invite critique, and let anyone implement them.

RFCs: Publishing the recipe

The Request for Comments (RFC) series turned networking ideas into shared, citable documents. Instead of a black-box standard controlled by one vendor, RFCs made the rules visible: what each field means, what to do in edge cases, and how to stay compatible.

That openness did two things. First, it reduced risk for adopters: universities, governments, and companies could evaluate the design and build against it. Second, it created a common reference point, so disagreements could be settled with updates to the text rather than private negotiations.

Interoperability unlocks ecosystems

Interoperability is what makes “multi-vendor” real. When different routers, operating systems, and applications can exchange traffic predictably, buyers aren’t trapped. Competition shifts from “whose network can you join?” to “whose product is better?”—which accelerates improvement and lowers costs.

Compatibility also creates network effects: each new TCP/IP implementation makes the whole network more valuable, because it can talk to everything else. More users attract more services; more services attract more users.

The limits: standards still take work

Open standards don’t remove friction—they redistribute it. RFCs involve debate, coordination, and sometimes slow change, especially when billions of devices already depend on today’s behavior. The upside is that change, when it happens, is legible and broadly implementable—preserving the core benefit: everyone can still connect.

From Protocols to Platforms: How Global Software Became Possible

When people say “platform,” they often mean a product with other people building on top of it: third‑party apps, integrations, and services that run on shared rails. On the internet, those rails are not a single company’s private network—they’re common protocols that anyone can implement.

The chain reaction from TCP/IP to modern platforms

TCP/IP didn’t create the web, cloud, or app stores by itself. It made a stable, universal foundation where those things could reliably spread.

Once networks could interconnect through IP and applications could rely on TCP for delivery, it became practical to standardize higher-level building blocks:

- The web (HTTP + browsers): one client could reach many servers, anywhere.

- APIs: services could expose functions over the network in a predictable way.

- SaaS and cloud: software moved from “installed locally” to “delivered over the network,” because the network was consistent enough to bet a business on.

- App ecosystems and marketplaces: distribution, updates, and integrations became normal expectations.

TCP/IP’s gift to platform economics was predictability: you could build once and reach many networks, countries, and device types without negotiating bespoke connectivity each time.

Stable protocols lower switching costs

A platform grows faster when users and developers feel they can leave—or at least aren’t trapped. Open, widely implemented protocols reduce switching costs because:

- Users can change providers while keeping familiar tools (email is the classic example).

- Developers can reuse skills and code across vendors (a request is still a request).

- New entrants can interoperate instead of starting from zero.

That “permissionless” interoperability is why global software markets could form around shared standards rather than around a single network owner.

Protocol-enabled building blocks (quick examples)

- HTTP made “fetch a resource from anywhere” a default behavior for software.

- TLS added confidentiality and integrity so commerce and identity could work at scale.

- SMTP turned email into a cross-provider system, not a walled garden.

These sit above TCP/IP, but they depend on the same idea: if the rules are stable and public, platforms can compete on product—without breaking the ability to connect.

Scaling Reality: Congestion, Latency, and the Need for Resilience

The Internet’s magic is that it works across oceans, mobile networks, Wi‑Fi hotspots, and overloaded office routers. The less magical truth: it’s always operating under constraints. Bandwidth is limited, latency varies, packets get lost or reordered, and congestion can appear suddenly when many people share the same path.

The constraints you can’t wish away

Even if your service is “cloud-based,” your users experience it through the narrowest part of the route to them. A video call on fiber and the same call on a crowded train are different products, because latency (delay), jitter (variation), and loss shape what users perceive.

Congestion control, conceptually

When too much traffic hits the same links, queues build up and packets drop. If every sender reacts by sending even more (or retrying too aggressively), the network can spiral into congestion collapse—lots of traffic, little useful delivery.

Congestion control is the set of behaviors that keep sharing fair and stable: probe for available capacity, slow down when loss/latency signals overload, then cautiously speed up again. TCP popularized this “back off, then recover” rhythm so the network could remain simple while endpoints adapt.

How this shaped product decisions

Because networks are imperfect, successful applications quietly do extra work:

- Caching to avoid repeating expensive trips (CDNs, local caches, memoized API responses).

- Retries with timeouts to recover from loss—but not instantly, and not forever.

- Exponential backoff so a struggling service isn’t hammered harder during an incident.

Practical guidance for platform teams

Design as if the network will fail, briefly and often:

- Make operations idempotent so retries don’t duplicate purchases or messages.

- Prefer graceful degradation (stale content, reduced quality) over total failure.

- Instrument latency percentiles and error rates by region/network type, not just averages.

Resilience isn’t an add-on feature—it’s the price of operating at Internet scale.

Security and Trust: What Early Assumptions Got Wrong

Keep code portable

Export the source code when you need full control or custom workflows.

TCP/IP succeeded because it made it easy for any network to connect to any other. The hidden cost of that openness is that anyone can also send you traffic—good or bad.

Open connectivity also enables abuse

Early internet design assumed a relatively small, research-oriented community. When the network became public, the same “just forward packets” philosophy enabled spam, fraud, malware delivery, denial-of-service attacks, and impersonation. IP doesn’t verify who you are. Email (SMTP) didn’t require proof you owned the “From” address. And routers were never meant to judge intent.

Security shifted from optional to foundational

As the internet turned into critical infrastructure, security stopped being a feature you could bolt on and became a requirement in how systems are built: identity, confidentiality, integrity, and availability needed explicit mechanisms. The network stayed mostly best-effort and neutral, but applications and platforms had to assume the wire is untrusted.

Mitigations built on top (briefly)

We didn’t “fix” IP by making it police every packet. Instead, modern security is layered above it:

- Encryption (e.g., TLS/HTTPS) to prevent eavesdropping and tampering

- Authentication (certificates, signed tokens, MFA) to prove identities

- Zero trust to avoid blanket trust based on network location

Practical guidance for platform teams

Treat the network as hostile by default. Use least privilege everywhere: narrow scopes, short-lived credentials, and strong defaults. Verify identities and inputs at every boundary, encrypt in transit, and design for abuse cases—not just happy paths.

Takeaways for Platform Teams: Design for Interconnection

The internet didn’t “win” because every network agreed on the same hardware, vendor, or perfect feature set. It lasted because key protocol choices made it easy for independent systems to connect, improve, and keep working even when parts fail.

The design decisions worth copying

Layering with clear seams. TCP/IP separated “moving packets” from “making applications reliable.” That boundary let the network stay general-purpose while apps evolved quickly.

Simplicity in the core. Best-effort delivery meant the network didn’t need to understand every application’s needs. Innovation happened at the edges, where new products could ship without negotiating with a central authority.

Interoperability first. Open specs and predictable behavior made it possible for different organizations to build compatible implementations—and created a compounding adoption loop.

Translate this into product strategy

If you’re building a platform, treat interconnection as a feature, not a side effect. Prefer a small set of primitives that many teams can compose over a large set of “smart” features that lock users into one path.

Design for evolution: assume clients will be old, servers will be new, and some dependencies will be partially down. Your platform should degrade gracefully and still be useful.

If you’re using a rapid-build environment like Koder.ai, the same principles show up as product capabilities: a clear planning step (so interfaces are explicit), safe iteration via snapshots/rollback, and predictable deployment/hosting behavior that lets multiple teams move fast without breaking consumers.

Checklist for platform builders

- APIs: Keep a stable core; add optional capabilities without breaking old clients.

- Compatibility: Version deliberately; avoid removing fields/behaviors; document guarantees.

- Failure behavior: Timeouts, retries with backoff, idempotency keys, and clear error codes.

- Interoperability: Publish schemas/specs; provide reference implementations and conformance tests.

- Observability: Correlation IDs, structured logs, and SLOs that reflect user experience.

- Change control: Deprecation windows, feature flags, and migration guides.

Next reads

- /blog/api-design-basics

- /blog/platform-strategy

- /blog/versioning-and-backward-compatibility

- /blog/graceful-degradation-patterns

FAQ

What is a protocol, and why does it matter for platform teams?

A protocol is a shared set of rules for how systems format messages, start/stop exchanges, handle missing data, and identify destinations. Platforms depend on protocols because they make interoperability predictable, so independent teams and vendors can integrate without custom one-off agreements.

What problem did “internetworking” solve compared to early standalone networks?

Internetworking is connecting multiple independent networks so packets can traverse them as one end-to-end journey. The key problem was doing this without forcing any network to rewrite its internals, which is why a common layer (IP) became so important.

How is packet switching different from circuit switching, and why did it win?

Packet switching breaks data into packets that share network links with other traffic, which is efficient for bursty computer communication. Circuit switching reserves a dedicated path end-to-end, which can be wasteful when traffic is intermittent (like most web/app traffic).

What’s the practical difference between IP and TCP in the TCP/IP design?

IP handles addressing and routing (moving packets hop-by-hop). TCP sits above IP and provides reliability when needed (ordering, retransmission, flow/connection control). This separation lets the network stay general-purpose while apps choose the delivery guarantees they require.

Why is the Internet “best-effort,” and how did that help it scale?

“Best-effort” means IP tries to deliver packets but does not guarantee arrival, order, or timing. This simplicity lowered the bar for networks to join (no strict guarantees required everywhere), which accelerated adoption and made global connectivity feasible even over imperfect links.

What is the end-to-end principle, and what trade-offs does it create?

It’s the idea that the network core should do as little as possible, and endpoints/applications should implement the “smarts” (reliability, security, recovery) when necessary. The benefit is faster innovation at the edges; the cost is that apps must explicitly handle failure, abuse, and variability.

How do addressing and routing enable the Internet to scale globally?

Addresses identify destinations; routing decides the next hop toward those destinations. Hierarchical addressing enables route aggregation, which keeps routing tables manageable at global scale. Poor aggregation increases operational complexity and can stress the routing system.

What role does DNS play beyond “making names human-readable”?

DNS maps human-friendly names (like api.example.com) to IP addresses, and it can change those mappings without changing clients. Platforms use DNS for traffic steering, multi-region deployments, and failover—keeping the name stable while infrastructure evolves underneath.

Why were open standards (RFCs) essential to Internet adoption and platform ecosystems?

RFCs publish protocol behavior openly so anyone can implement it and test compatibility. That openness reduces vendor lock-in, increases multi-vendor interoperability, and creates network effects: each additional compatible implementation increases the value of the whole ecosystem.

What are the most practical protocol-inspired lessons for modern platform reliability and security?

Build as if the network will be unreliable:

- Use timeouts and retries with exponential backoff.

- Make operations idempotent so retries don’t double-charge or duplicate work.

- Measure latency by percentiles and by region/network type.

- Encrypt in transit (TLS) and treat the network as untrusted.

For related guidance, see /blog/versioning-and-backward-compatibility and /blog/graceful-degradation-patterns.