Sep 15, 2025·8 min

Vitalik Buterin and Ethereum: A Platform Layer for Apps

How Vitalik Buterin’s Ethereum turned programmable money into a platform layer for apps—by pairing smart contracts with a thriving developer ecosystem.

How Vitalik Buterin’s Ethereum turned programmable money into a platform layer for apps—by pairing smart contracts with a thriving developer ecosystem.

Ethereum is closely tied to Vitalik Buterin because he helped articulate the original proposal: a blockchain that could run general-purpose programs, not just move a single coin from A to B. Instead of building a new chain for every new idea, developers could build on one shared base that anyone can access.

If regular money is a number in a bank account, programmable money is money with rules. Those rules can say things like: release payment only when a condition is met, split revenue automatically, or let people trade tokens without a central company holding the funds. The key point is that the logic is enforced by software on the network—so participants can coordinate without needing a single trusted operator.

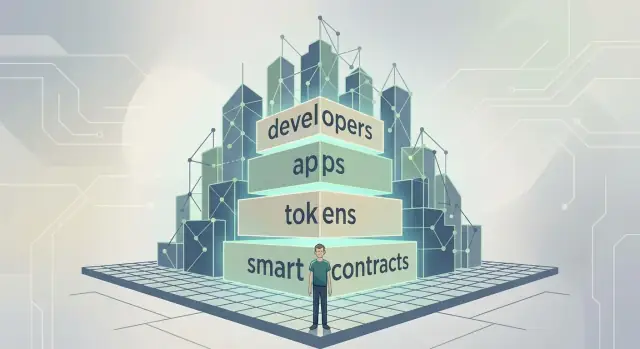

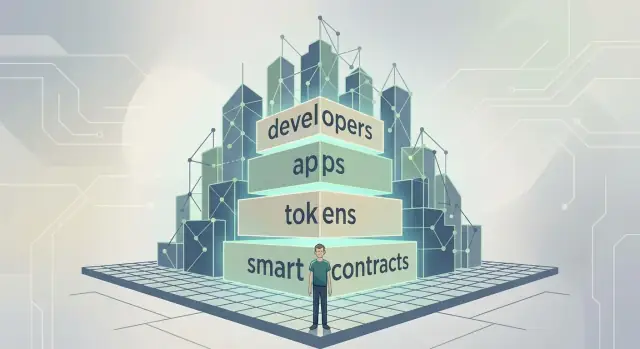

Ethereum reframed a blockchain as a platform layer: a common “world computer” where apps share the same security, user accounts, and data standards. That makes it possible for different applications to plug into each other—wallets, tokens, marketplaces, lending protocols—without asking permission from a platform owner.

This post connects four threads:

By the end, you should have a practical mental model for why Ethereum became more than a coin: it became a shared foundation that enabled entire categories of web3 apps.

Bitcoin’s breakthrough wasn’t just “internet money.” It proved digital scarcity: a way for strangers to agree on who owns what without a central operator.

But Bitcoin was intentionally narrow. Its built-in scripting system could express a few useful conditions (like multi-signature spending), yet it was designed to be simple, predictable, and hard to abuse. That conservatism helped security, but it also limited what you could build.

If you wanted to create an app on top of early crypto—say a token, a crowdfunding mechanism, or an on-chain game—you quickly ran into constraints:

So the choice was often: keep logic off-chain (giving up the “trustless” benefits), or launch a separate blockchain (giving up shared users and infrastructure).

What builders needed was a general-purpose, shared execution environment—a place where anyone could deploy code, and everyone could verify its results. If that existed, an “app” could be a program living on-chain, not a company running servers.

That gap is the heart of Ethereum’s original proposal: a blockchain that treats smart contract code as a first-class citizen—turning crypto from a single-purpose system into a platform for many applications.

Bitcoin proved that digital value could move without a central operator—but building anything beyond “send and receive” was awkward. New features often required changes to the underlying protocol, and every new idea tended to become its own chain. That made experimentation slow and fractured.

Vitalik Buterin’s core proposal was simple: instead of creating a blockchain for one use case, create a blockchain that can run many use cases. Not “a coin with a few extra functions,” but a shared foundation where developers can write programs that define how value behaves.

You’ll sometimes hear Ethereum described as a “world computer.” The useful meaning isn’t that it’s a supercomputer—it’s that Ethereum is a public, always-on platform where anyone can deploy code, and anyone else can interact with it. The network acts like a neutral referee: it executes the same rules for everyone and records the results in a way that others can verify.

Ethereum wasn’t only about smart contracts; it was about making them interoperable by default. If developers follow shared standards, different apps can snap together like building blocks: a wallet can work with many tokens, an exchange can list new assets without custom integrations, and a new product can reuse existing components instead of rebuilding them from scratch.

This is where open standards and composability become a feature, not an accident. Contracts can call other contracts, and products can stack on top of earlier “primitives.”

The end goal was a platform layer: a dependable base where countless applications—financial tools, digital ownership, organizations, games—could be built and recombined. Ethereum’s bet was that a general-purpose foundation would unlock more innovation than a collection of single-purpose chains.

Smart contracts are small programs that run on Ethereum and enforce rules exactly as written. A simple analogy is a vending machine: you insert $2, press a button, and the machine dispenses a snack—no cashier, no negotiating, no “we’ll do it later.” The rules are visible, and the outcome is automatic when the inputs are correct.

In a normal app, you trust a company’s servers, admins, database updates, and customer support process. If they change the rules, freeze your account, or make an error, you usually have no direct way to verify what happened.

With a smart contract, the key logic is executed by the network. That means participants don’t have to trust a single operator to follow through—assuming the contract is correctly written and deployed. You still trust the code and the underlying blockchain, but you’re reducing reliance on a central party’s discretion.

Smart contracts can:

They can’t directly know real-world facts on their own—like today’s weather, a delivery status, or whether someone is over 18. For that, they need external inputs (often called oracles). They also can’t “undo” mistakes easily: once deployed and used, changing a contract’s behavior is difficult and sometimes impossible.

Because assets and rules can live in the same place, you can build products where payments, ownership, and enforcement happen together. That enables things like automatic revenue splits, transparent marketplaces, programmable memberships, and financial agreements that settle by code—not by paperwork or manual approval.

Ethereum is a shared computer that many independent parties agree on. Instead of one company running the server, thousands of nodes verify the same set of rules and keep the same history.

Ethereum has accounts that can hold ETH and interact with apps. There are two main types:

A transaction is a signed message from an EOA that either (1) sends ETH to another account or (2) calls a smart contract function. For users, this is what “confirming in your wallet” actually does. For developers, it’s the basic unit of interaction: every app action ultimately becomes a transaction.

Transactions don’t take effect instantly. They get grouped into blocks, and blocks are added to the chain in order. Once your transaction is included in a block (and followed by more blocks), it becomes increasingly hard to reverse. Practically: you wait for confirmations; builders design UX around that delay.

The Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) is the shared runtime that executes smart contract code the same way on every node. This is why contracts are portable: if you deploy a token, an exchange, or an NFT contract, any wallet or app can interact with it as long as they speak the same EVM “language.”

Every computation and storage change costs gas. Gas exists to:

For users, gas is the fee you pay to get included. For developers, gas shapes product design: efficient contracts can make apps cheaper, while complex interactions can become expensive when the network is congested.

Ethereum didn’t just add “smart contracts.” It also popularized a shared set of token standards—common rules that wallets, exchanges, and apps can rely on. That compatibility is a big reason the ecosystem could grow quickly: when everyone speaks the same “token language,” new apps plug into existing infrastructure instead of rebuilding it.

A token standard defines things like how balances are tracked, how transfers work, and which basic functions every token contract should expose. If a wallet knows those functions, it can display and send any compliant token. If a DeFi app supports the standard, it can accept many tokens with minimal extra work.

This reduces integration effort from “custom work for every asset” to “support the standard once.” It also lowers the risk of mistakes, because developers reuse battle-tested patterns.

ERC-20 is the blueprint for fungible tokens—assets where each unit is interchangeable (like dollars). A stablecoin, a governance token, or a points-like utility token can all follow the same interface.

Because ERC-20 is predictable, exchanges can list new tokens faster, wallets can show balances automatically, and DeFi protocols can treat many assets consistently (for swapping, lending, collateral, and more).

ERC-721 is the classic NFT standard: each token is unique, making it well-suited for collectibles, tickets, and proof of ownership.

ERC-1155 extends the idea by letting one contract manage many token types—both fungible and non-fungible—useful for games and apps that need large sets of items.

Together, these standards turned “custom assets” into interoperable building blocks—so creators and developers spend less time on plumbing and more time on products.

Ethereum didn’t become a platform layer only because of smart contracts—it also grew because building on it got easier over time. As more developers joined, they created tools, shared patterns, and reusable building blocks. That lowered the effort for the next wave of builders, which attracted even more people.

Composability means one app can plug into another app’s smart contracts, like Lego pieces. Instead of reinventing everything, a new product can reuse existing contracts and focus on a better user experience.

An approachable example: you open a wallet, connect to a swap app to trade ETH for a stablecoin, then send that stablecoin into a lending app to earn interest—all in a few clicks. Under the hood, each step can call well-known contracts that many other apps also use.

Another example: a portfolio app can “read” your positions across multiple DeFi protocols without needing permission, because the data is on-chain and the contracts are publicly accessible.

Early teams built the basics: wallet libraries, contract templates, security tooling, and developer frameworks. Later builders benefited from that foundation and shipped faster, which increased usage and made the ecosystem even more attractive.

Open-source is a major accelerant here. When a team publishes audited contract code or a widely used library, thousands of other developers can inspect it, improve it, and adapt it. Iteration happens in public, standards spread quickly, and good ideas compound.

In practice, this flywheel increasingly extends beyond Solidity itself into everything around it: frontends, dashboards, admin tooling, and backend services that index chain activity. Platforms like Koder.ai fit here as a modern “vibe-coding” layer: you describe the product in chat and generate a working web app (React), backend (Go + PostgreSQL), or mobile app (Flutter), then iterate quickly—useful for prototypes like token-gated pages, analytics panels, or internal ops tools that sit alongside on-chain contracts.

Ethereum’s biggest shift wasn’t a single “killer app.” It was the creation of reusable building blocks—smart contracts that behave like open financial and digital primitives. Once those primitives existed, teams could combine them into products quickly, often without asking permission from a platform owner.

Decentralized finance (DeFi) grew from a few core patterns that keep reappearing:

What matters is how these pieces interlock: a stablecoin can be used as collateral in lending; lending positions can be used elsewhere; swaps provide liquidity to move between assets. This composability is how primitives turn into full financial products.

NFTs (commonly associated with art) are more broadly unique on-chain identifiers. That makes them useful for:

DAOs use smart contracts to manage group decision-making and shared treasuries. Instead of a company’s internal database, the “rules of the organization” (voting, spending limits, proposal flow) are visible and enforceable on-chain—useful for communities, grant programs, and protocols that need transparent governance.

Ethereum’s biggest strength—running apps without a central operator—also creates real constraints. A global network that anyone can verify will never feel as “instant and cheap” as a centralized service, and the trade-offs show up most clearly in fees, safety, and day-to-day usability.

Every transaction competes for limited space in each block. When demand spikes (popular NFT mints, volatile markets, major airdrops), users bid up fees to get included sooner. That can turn a simple action—swapping tokens, minting, or voting in a DAO—into an expensive decision.

High fees don’t just hurt wallets; they change product design. Apps may bundle actions, delay non-urgent updates, or limit features to keep costs reasonable. For new users, seeing “gas” and fluctuating fees can be confusing—especially when the cost is higher than the value being moved.

Smart contracts are powerful, but code can fail. A bug in a contract can freeze funds or allow an attacker to drain them, and “upgradeable” contracts add another layer of trust assumptions. On top of that, phishing links, fake token contracts, and deceptive approvals are common.

Unlike a bank transfer, many blockchain actions are effectively irreversible. If you sign the wrong transaction, there may be no support desk to call.

Ethereum prioritizes broad participation and verifiability. Keeping the system open and censorship-resistant limits how much it can “just scale up” on the base layer without making it too hard for regular participants to validate.

These realities are why scaling became a major focus: improving the experience without giving up the properties that make Ethereum valuable in the first place.

Ethereum can feel like a busy highway: when lots of people try to use it at once, fees rise and transactions can take longer. Layer 2s (L2s) are one of the main ways Ethereum scales without giving up on the core idea that Ethereum L1 stays a neutral, highly secure base.

A Layer 2 is a network that sits “on top” of Ethereum. Instead of every user action being processed individually on Ethereum mainnet, an L2 batches many transactions together, does most of the work off-chain, and then posts a compressed proof or summary back to Ethereum.

Think of it like:

Fees on Ethereum largely reflect how much computation and data you ask the network to process. If 10,000 swaps or transfers can be bundled into a much smaller amount of data posted to L1, the L1 cost is shared across many users.

That’s why L2s can often provide:

To use an L2, you usually move assets between Ethereum L1 and the L2 through a bridge. Bridges are essential because they let the same value (ETH, stablecoins, NFTs) flow to where transactions are cheaper.

But bridges also add complexity and risk:

For everyday users, it’s worth checking what an app recommends, reading the bridge steps carefully, and sticking to well-known options.

L2s reinforce Ethereum’s role as a platform layer: Ethereum mainnet focuses on security, neutrality, and final settlement, while many different L2s compete on speed, cost, and user experience.

Instead of one chain trying to do everything, Ethereum becomes a base that can support many “cities” (L2s) on top—each optimized for different kinds of web3 apps, while still anchoring back to the same underlying system of assets and smart contracts.

Ethereum didn’t become influential just because its token had value. It became a place where things get built—a shared execution layer where apps, assets, and users can interact through the same rules.

Technology matters, but it rarely wins alone. What changes the trajectory of a platform is developer mindshare: the number of builders who choose it first, teach it, write tutorials for it, and ship real products on it.

Ethereum made it unusually easy to go from idea to on-chain program with a common runtime (the EVM) and a widely understood contract model. That attracted tooling, audits, wallets, exchanges, and communities—making it easier for the next team to build.

Ethereum popularized the idea that shared standards can unlock entire markets. ERC-20 made tokens interoperable across wallets and exchanges; ERC-721 helped formalize NFTs; and later standards extended those building blocks.

Once assets follow common interfaces, liquidity can concentrate: a token can be traded, used as collateral, routed through a DEX, or integrated into a wallet without bespoke work. That liquidity, plus composability (“apps plugging into apps”), becomes a practical moat—not because others can’t copy code, but because coordination and adoption are hard to replicate.

Other chains often optimize different trade-offs: higher throughput, lower fees, alternative virtual machines, or more centralized governance for faster upgrades. Ethereum’s standout contribution wasn’t claiming the only path—it was popularizing a general-purpose smart contract platform with shared standards that let independent teams build on top of each other.

Ethereum apps can feel abstract until you evaluate them the same way you’d evaluate any financial product: what it does, what it costs, and what could go wrong. Here are practical filters that work whether you’re swapping tokens, minting an NFT, or joining a DAO.

If you’re building, treat Ethereum mainnet as the settlement layer and Layer 2s as your distribution layer.

For a plain-English overview of trade-offs, you might link readers to: /blog/layer-2s-explained

One practical workflow tip: because most web3 products are a blend of on-chain contracts and off-chain UX (frontends, indexers, admin panels, customer support tooling), fast iteration matters. Tools like Koder.ai can help teams go from “idea to usable interface” quickly by generating and refining React frontends and Go/PostgreSQL backends via chat, with options like source-code export, snapshots/rollback, and deployment—handy when you’re testing an L2 strategy or shipping a dashboard for real users.

Programmable money is likely to keep expanding—more apps, more standards, more “money legos”—but not in a straight line. Fees, user safety, and complexity are real constraints, and better scaling plus better wallet UX will matter as much as new protocols.

The long-term direction looks consistent: Ethereum as a credible base layer for security and settlement, with faster and cheaper execution pushed to L2s—while users get more choice, and builders get clearer patterns for shipping responsibly.

Ethereum is a general-purpose blockchain that can run programs (smart contracts), not just transfer a single native coin.

Practically, that means developers can deploy shared “backend” logic on-chain—tokens, marketplaces, lending, governance—and any wallet or app can interact with it.

“Programmable money” is value that moves only when rules are satisfied.

Examples include:

A smart contract is code deployed on Ethereum that holds assets and enforces rules automatically.

You send a transaction to call a function; the network executes it the same way on every node and records the result on-chain.

EOAs (Externally Owned Accounts) are controlled by a private key in your wallet; they initiate transactions.

Contract accounts are controlled by code; they react when called and can hold tokens, run logic, and restrict permissions based on their programmed rules.

The EVM (Ethereum Virtual Machine) is the shared runtime that executes contract code.

Because the EVM is standardized, contracts are “portable”: wallets and apps can interact with many different contracts as long as they follow common interfaces (like token standards).

Gas is a fee mechanism that prices computation and storage changes.

It exists to:

ERC-20 is a standard interface for fungible tokens (units are interchangeable).

Because wallets, exchanges, and DeFi apps know the ERC-20 “shape,” they can support many tokens with far less custom integration.

ERC-721 is the classic NFT standard for unique tokens (each token ID is distinct).

ERC-1155 lets one contract manage many token types (fungible and non-fungible), which is useful for games and apps that need lots of items without deploying tons of contracts.

Layer 2s batch many user transactions, execute most work off-chain, and then post a compressed proof or summary to Ethereum (L1).

This usually means lower fees and faster confirmations, while L1 remains the high-security settlement layer.

Start with basics:

If you want a primer on the scaling trade-offs, see /blog/layer-2s-explained.