Mar 17, 2025·8 min

VMware and Broadcom: When Virtualization Becomes the Control Plane

A plain-English look at how VMware evolved into enterprise IT’s control plane, and what Broadcom ownership may change for budgets, tools, and teams.

A plain-English look at how VMware evolved into enterprise IT’s control plane, and what Broadcom ownership may change for budgets, tools, and teams.

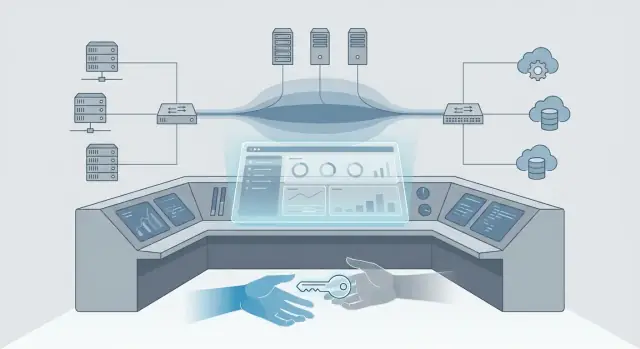

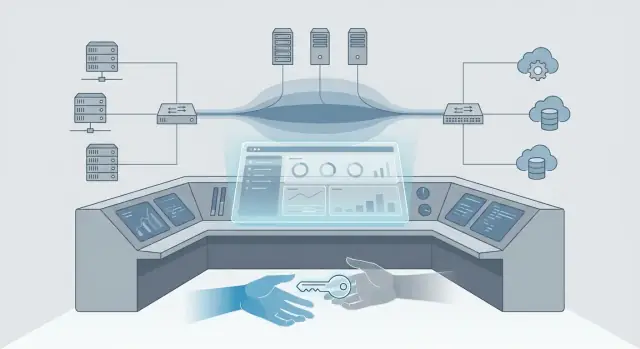

Virtualization, in plain terms, is a way to run many “virtual” servers on one physical machine—so one box can safely behave like many. A control plane is the set of tools and rules that tells a system what should run where, who can change it, and how it’s monitored. If virtualization is the engine, the control plane is the dashboard, steering wheel, and traffic laws.

VMware didn’t just help organizations buy fewer servers. Over time, vSphere and vCenter became the place where teams:

That’s why VMware matters beyond “running VMs.” In many enterprises, it effectively became the operating layer for infrastructure—the point where decisions are enforced and audited.

This article looks at how virtualization grew into an enterprise control plane, why that position is strategically important, and what tends to change when ownership and product strategy shift. We’ll cover the history briefly, then focus on practical impacts for IT teams: operations, budgeting signals, risk, ecosystem dependencies, and realistic options (stay, diversify, or migrate) over the next 6–18 months.

We won’t guess at confidential roadmaps or predict specific commercial moves. Instead, we’ll focus on observable patterns: what typically shifts first after an acquisition (packaging, licensing, support motions), how those shifts affect day-to-day operations, and how to make decisions with incomplete information—without freezing or overreacting.

Virtualization didn’t start as a grand “platform” idea. It started as a practical fix: too many underused servers, too much hardware sprawl, and too many late-night outages caused by one application owning an entire physical box.

In the early days, the pitch was straightforward—run multiple workloads on one physical host and stop buying so many servers. That quickly evolved into an operational habit.

Once virtualization became common, the biggest win wasn’t just “we saved money on hardware.” It was that teams could repeat the same patterns everywhere.

Instead of every location having a unique server setup, virtualization encouraged a consistent baseline: similar host builds, common templates, predictable capacity planning, and shared practices for patching and recovery. That consistency mattered across:

Even when the underlying hardware differed, the operational model could stay mostly the same.

As environments grew, the center of gravity shifted from individual hosts to centralized management. Tools like vCenter didn’t just “manage virtualization”—they became where administrators handled routine work: access control, inventory, alarms, cluster health, resource allocation, and safe maintenance windows.

In many organizations, if it wasn’t visible in the management console, it effectively wasn’t manageable.

A single standard platform can outperform a collection of best-of-breed tools when you value repeatability. “Good enough everywhere” often means:

That’s how virtualization moved from a cost-saving tactic into standard practice—and set the stage for becoming an enterprise control plane.

Virtualization started as a way to run more workloads on fewer servers. But once most applications lived on a shared virtual platform, the “place you click first” became the place where decisions get enforced. That’s how a hypervisor stack evolves into an enterprise control plane.

IT teams aren’t only managing “compute.” Day-to-day operations span:

When these layers are orchestrated from one console, virtualization becomes the practical center of operations—even when the underlying hardware is diverse.

A key shift is that provisioning becomes policy-driven. Instead of “build a server,” teams define guardrails: approved images, sizing limits, network zones, backup rules, and permissions. Requests translate into standardized outcomes.

That’s why platforms like vCenter end up functioning like an operating system for the data center: not because they run your apps, but because they decide how apps are created, placed, secured, and maintained.

Templates, golden images, and automation pipelines quietly lock in behaviors. Once teams standardize on a VM template, a tagging scheme, or a workflow for patching and recovery, it spreads across departments. Over time, the platform isn’t just hosting workloads—it’s embedding operating habits.

When one console runs “everything,” the center of gravity moves from servers to governance: approvals, compliance evidence, separation of duties, and change control. That’s why ownership or strategy changes don’t only affect pricing—they affect how IT runs, how fast it can respond, and how safely it can change.

When people call VMware a “control plane,” they don’t mean it’s just where virtual machines run. They mean it’s the place where daily work is coordinated: who can do what, what is safe to change, and how problems are detected and resolved.

Most IT effort happens after the initial deployment. In a VMware environment, the control plane is where Day‑2 operations live:

Because these tasks are centralized, teams build repeatable runbooks around them—change windows, approval steps, and “known good” sequences.

Over time, VMware knowledge becomes operational muscle memory: naming standards, cluster design patterns, and recovery drills. That’s hard to replace not because alternatives don’t exist, but because consistency reduces risk. A new platform often means re-learning edge cases, rewriting runbooks, and re-validating assumptions under pressure.

During an outage, responders rely on the control plane for:

If those workflows change, mean time to recovery can change too.

Virtualization rarely stands alone. Backup, monitoring, disaster recovery, configuration management, and ticketing systems integrate tightly with vCenter and its APIs. DR plans may assume specific replication behavior; backup jobs may depend on snapshots; monitoring may rely on tags and folders. When the control plane shifts, these integrations are often the first “surprises” you’ll need to inventory and test.

When a platform as central as VMware changes owners, the technology usually doesn’t break overnight. What shifts first is the commercial wrapper around it: how you buy it, how you renew it, and what “normal” looks like in budgeting and support.

Many teams still get enormous operational value from vSphere and vCenter—standardized provisioning, consistent operations, and a familiar toolchain. That value can remain steady even while the commercial terms change quickly.

It helps to treat these as two different conversations:

New ownership often brings a mandate to simplify the catalog, increase average contract value, or shift customers into fewer bundles. That can translate into changes in:

The most practical worries tend to be boring but real: “What will this cost next year?” and “Can we get multi-year predictability?” Finance wants stable forecasts; IT wants assurance that renewal doesn’t force rushed architectural decisions.

Before you talk numbers, build a clean fact base:

With that in hand, you can negotiate from clarity—whether your plan is to stay, diversify, or prepare a migration path.

When a platform vendor changes strategy, the first thing many teams feel isn’t a new feature—it’s a new way of buying and planning. For VMware customers watching Broadcom’s direction, the practical impact often shows up in bundles, roadmap priorities, and which products get the most attention.

Bundling can be genuinely helpful: fewer SKUs, fewer “did we buy the right add-on?” debates, and clearer standardization across teams.

The trade-off is flexibility. If the bundle includes components you don’t use (or don’t want to standardize on), you may end up paying for shelfware or being pushed toward a “one size fits most” architecture. Bundles can also make it harder to pilot alternatives gradually—because you’re no longer buying just the piece you need.

Product roadmaps tend to favor the customer segments that drive the most revenue and renewals. That can mean:

None of that is inherently bad—but it changes how you should plan upgrades and dependencies.

If certain capabilities are deprioritized, teams often fill gaps with point solutions (backup, monitoring, security, automation). That can solve immediate problems while creating long-term tool sprawl: more consoles, more contracts, more integrations to maintain, and more places for incidents to hide.

Ask for clear commitments and boundaries:

These answers turn “strategy shift” into concrete planning inputs for budgets, staffing, and risk.

When VMware is treated as a control plane, a licensing or packaging change doesn’t stay in procurement. It changes how work flows through IT: who can approve changes, how quickly environments can be provisioned, and what “standard” means across teams.

Platform administrators often feel the first-order effects. If entitlements are simplified into fewer bundles, day-to-day operations can become less flexible: you may need internal approval to use a feature that used to be “just there,” or you may have to standardize on fewer configurations.

That shows up as more admin workload in places people don’t always see—license checks before projects start, tighter change windows to align upgrades, and more coordination with security and app teams around patching and configuration drift.

App teams are usually measured on performance and uptime, but platform shifts can change the underlying assumptions. If clusters are rebalanced, host counts change, or feature usage is adjusted to match new entitlements, application owners may need to re-test compatibility and re-baseline performance.

This is especially true for workloads that rely on specific storage, networking, or HA/DR behaviors. The practical outcome: more structured testing cycles and clearer documentation of “what this app needs” before changes are approved.

If the virtualization layer is your enforcement point for segmentation, privileged access, and audit trails, any shift in tooling or standard configurations affects compliance.

Security teams will push for clearer separation of duties (who can change what in vCenter operations), consistent logging retention, and fewer “exception” configurations. IT teams should expect more formalized access reviews and change records.

Even if the trigger is cost, the impact is operational: chargeback/showback models may need to be updated, cost centers may renegotiate what they consider “included,” and forecasting becomes a collaboration with platform teams.

A good sign you’re treating virtualization as a control plane is when IT and finance plan together instead of reconciling surprises after renewal.

When a platform like VMware shifts ownership and strategy, the biggest risks often show up in the “quiet” parts of IT: continuity plans, support expectations, and day‑to‑day operational safety. Even if nothing breaks immediately, assumptions you’ve relied on for years can change.

A major platform shift can ripple into backup, disaster recovery, and retention in subtle ways. Backup products may depend on specific APIs, vCenter permissions, or snapshot behavior. DR runbooks often assume certain cluster features, networking defaults, and orchestration steps. Retention plans may also be affected if storage integrations or archive workflows change.

Actionable takeaway: validate your end-to-end restore process (not just backup success) for the systems that matter most—tier 0 identity, management tooling, and key business apps.

Common risk areas are operational rather than contractual:

The practical risk is downtime from “unknown unknowns,” not just higher costs.

When one platform dominates, you gain standardization, a smaller skills footprint, and consistent tooling. The trade-off is dependency: fewer escape routes if licensing, support, or product focus shifts. Concentration risk is highest when VMware underpins not only workloads, but identity, backups, logging, and automation.

Document what you actually run (versions, dependencies, and integration points), tighten access reviews for vCenter/admin roles, and set a testing cadence: quarterly restore tests, semiannual DR exercises, and a pre-upgrade validation checklist that includes hardware compatibility and third‑party vendor confirmations.

These steps reduce operational risk no matter which direction your strategy takes next.

VMware rarely operates alone. Most environments depend on a web of hardware vendors, managed service providers (MSPs), backup platforms, monitoring tools, security agents, and disaster recovery services. When ownership and product strategy change, the “blast radius” often shows up first in this ecosystem—sometimes before you notice it inside vCenter.

Hardware vendors, MSPs, and ISVs align their support to specific versions, editions, and deployment patterns. Their certifications and support matrices determine what they will troubleshoot—and what they’ll ask you to upgrade before they engage.

A licensing or packaging change can indirectly force upgrades (or prevent them), which then affects whether your server model, HBA, NIC, storage array, or backup proxy remains on the supported list.

Many third-party tools have historically priced or packaged around “per socket,” “per host,” or “per VM” assumptions. If the platform’s commercial model changes, those tools may adjust how they count usage, what features require an add-on, or which integrations are included.

Support expectations can shift too. For example, an ISV might require specific API access, plugin compatibility, or minimum vSphere/vCenter versions to support an integration. Over time, “it used to work” becomes “it works, but only on these versions and these tiers.”

Containers and Kubernetes often reduce pressure on VM sprawl, but they don’t eliminate the need for virtualization in many enterprises. Teams commonly run Kubernetes on VMs, depend on virtual networking and storage policies, and use existing backup and DR patterns.

That means interoperability between container tooling and the virtualization layer still matters—especially around identity, networking, storage, and observability.

Before committing to “stay, diversify, or migrate,” inventory the integrations you rely on: backups, DR, monitoring, CMDB, vulnerability scanning, MFA/SSO, network/security overlays, storage plugins, and MSP runbooks.

Then validate three things: what’s supported today, what’s supported on your next upgrade, and what becomes unsupported if packaging/licensing changes alter the way you deploy or manage the platform.

Once virtualization functions as your day-to-day control plane, change can’t be treated as a simple “platform swap.” Most organizations end up on one of four paths—sometimes in combination.

Staying isn’t the same as “doing nothing.” It usually means tightening inventory, standardizing cluster designs, and removing accidental sprawl so you’re paying for what you actually run.

If your primary goal is cost control, start by right-sizing hosts, reducing underused clusters, and validating which features you truly need. If your goal is resilience, focus on operational hygiene: patch cadence, backup testing, and documented recovery steps.

Optimization is the most common near-term move because it lowers risk and buys time. Typical actions include consolidating management domains, cleaning up templates/snapshots, and aligning storage/network standards so future migrations are less painful.

Diversification works best when you pick “safe” zones to introduce another stack without re-platforming everything at once. Common fits include:

The goal is usually vendor diversification or agility, not immediate replacement.

“Migrating” means more than moving VMs. Plan for the full bundle: workloads, networking (VLANs, routing, firewalls, load balancers), storage (datastores, replication), backups, monitoring, identity/access, and—often underestimated—skills and operating procedures.

Set realistic goals up front: are you optimizing for price, speed of delivery, risk reduction, or strategic flexibility? Clear priorities prevent a migration from turning into an endless rebuild.

If VMware is your operational control plane, decisions about VMware/Broadcom strategy shifts shouldn’t start with a vendor press release—they should start with your environment. Over the next 6–18 months, aim to replace assumptions with measurable facts, then choose a path based on risk and operational fit.

Create an inventory that your operations team would trust during an incident, not a spreadsheet built for procurement.

This inventory is the foundation for understanding what vCenter operations truly enable—and what would be hard to reproduce elsewhere.

Before debating vSphere licensing or alternative platforms, quantify your baseline and remove obvious waste.

Focus on:

Right-sizing can reduce virtualization costs immediately and makes any migration planning more accurate.

Write down your decision criteria and weight them. Typical categories:

Pick one representative workload (not the easiest) and run a pilot with:

Treat the pilot as a rehearsal for Day‑2 operations—not just a migration demo.

In real environments, a big part of the control plane is the set of small systems around it: inventory trackers, renewal dashboards, access review workflows, runbook checklists, and change-window coordination.

If you need to build or modernize that tooling quickly, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help teams create lightweight internal web apps through a chat interface (with planning mode, snapshots/rollback, and source code export). For example, you can prototype a vCenter integration inventory app or a renewal readiness dashboard (React front end, Go + PostgreSQL back end), host it with a custom domain, and iterate fast as requirements change—without waiting for a full development cycle.

You don’t need a finished “platform strategy” to make progress. The goal this week is to reduce uncertainty: know your dates, know your coverage, and know who needs to be in the room when decisions land.

Start with facts you can point to in a meeting.

Ownership and licensing shifts can create surprises when different teams hold different pieces of the puzzle.

Bring together a short working group: platform/virtualization, security, app owners, and finance/procurement. Agree on:

Aim for “good enough to estimate risk and cost,” not a perfect inventory.

Treat this as an ongoing management cycle, not a one-time event.

Review quarterly: vendor roadmap/licensing updates, run-rate costs vs. budget, and operational KPIs (incident volume, patch compliance, recovery test results). Add outcomes to your next renewal and migration planning notes.

A hypervisor runs VMs. A control plane is the decision-and-governance layer that determines:

In many enterprises, vCenter becomes the “place you click first,” which is why it functions like a control plane, not just a virtualization tool.

Because the operational value concentrates in standardization and repeatability, not just consolidation. vSphere/vCenter often becomes the common surface for:

Once those habits are embedded, changing the platform affects day‑2 operations as much as it affects where VMs run.

Day‑2 operations are the recurring tasks that fill calendars after initial deployment. In a VMware-centric environment, that typically includes:

If your runbooks assume these workflows, the management layer is effectively part of your operational system.

Because they’re what fail first when assumptions change. Common hidden dependencies include:

Inventory these early and test them during upgrades or pilots, not after a renewal forces a timeline.

Usually the commercial wrapper changes before the technology does. Teams most often feel shifts in:

Treat it as two tracks: preserve product value operationally, while de-risking commercial uncertainty contractually.

Build a fact base so procurement conversations aren’t guesswork:

This lets you negotiate with clarity and evaluate alternatives with realistic scope.

It can slow recovery and increase risk because responders depend on the control plane for:

If tooling, roles, or workflows change, plan for retraining, role redesign, and updated incident runbooks before you assume MTTR stays the same.

Not always. Bundles can simplify buying and standardize deployments, but the trade-offs are real:

Practical step: map each bundled component to a real operational need (or a clear plan to adopt it) before accepting it as “the new standard.”

Start by reducing uncertainty and buying time:

These steps lower risk whether you stay, diversify, or migrate.

Use a controlled pilot that tests operations, not just migration mechanics:

Treat the pilot as a rehearsal for day‑2 operations—patching, monitoring, backups, and access control—not a one-time demo.