Oct 18, 2025·8 min

How to Build a Web App for Data Imports, Exports & Validation

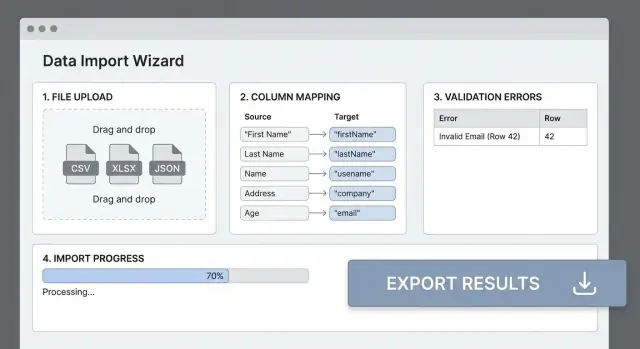

Learn how to design a web app that imports and exports CSV/Excel/JSON, validates data with clear errors, supports roles, audit logs, and reliable processing.

Learn how to design a web app that imports and exports CSV/Excel/JSON, validates data with clear errors, supports roles, audit logs, and reliable processing.

Before you design screens or pick a file parser, get specific about who is moving data in and out of your product and why. A data import web app built for internal operators will look very different from a self-serve Excel import tool used by customers.

Start by listing the roles that will touch imports/exports:

For each role, define the expected skill level and tolerance for complexity. Customers typically need fewer options and much better in-product explanations.

Write down your top scenarios and prioritize them. Common ones include:

Then define success metrics you can measure. Examples: fewer failed imports, faster time-to-resolution for errors, and fewer support tickets about “my file won’t upload.” These metrics help you make tradeoffs later (e.g., investing in clearer error reporting vs. more file formats).

Be explicit about what you will support on day one:

Finally, identify compliance needs early: whether files contain PII, retention requirements (how long you store uploads), and audit requirements (who imported what, when, and what changed). These decisions affect storage, logging, and permissions across the whole system.

Before you think about a fancy column mapping UI or CSV import validation rules, pick an architecture your team can ship and operate confidently. Imports and exports are “boring” infrastructure—speed of iteration and debuggability beat novelty.

Any mainstream web stack can power a data import web app. Choose based on existing skills and hiring realities:

The key is consistency: the stack should make it easy to add new import types, new data validation rules, and new export formats without rewrites.

If you want to accelerate scaffolding without committing to a one-off prototype, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can be helpful here: you can describe your import flow (upload → preview → mapping → validation → background processing → history) in chat, generate a React UI with a Go + PostgreSQL backend, and iterate quickly using planning mode and snapshots/rollback.

Use a relational database (Postgres/MySQL) for structured records, upserts, and audit logs for data changes.

Store original uploads (CSV/Excel) in object storage (S3/GCS/Azure Blob). Keeping raw files is invaluable for support: you can reproduce parsing issues, rerun jobs, and explain error handling decisions.

Small files can run synchronously (upload → validate → apply) for a snappy UX. For larger files, move work into background jobs:

This also sets you up for retries and rate-limited writes.

If you’re building SaaS, decide early how you separate tenant data (row-level scoping, separate schemas, or separate databases). This choice affects your data export API, permissions, and performance.

Write down targets for uptime, max file size, expected rows per import, time-to-complete, and cost limits. These numbers drive job queue choice, batching strategy, and indexing—long before you polish UI.

The intake flow sets the tone for every import. If it feels predictable and forgiving, users will try again when something goes wrong—and support tickets drop.

Offer a drag-and-drop zone plus a classic file picker for the web UI. Drag-and-drop is faster for power users, while the file picker is more accessible and familiar.

If your customers import from other systems, add an API endpoint too. It can accept multipart uploads (file + metadata) or a pre-signed URL flow for larger files.

On upload, do lightweight parsing to create a “preview” without committing data yet:

This preview powers later steps like column mapping and validation.

Always store the original file securely (object storage is typical). Keep it immutable so you can:

Treat each upload as a first-class record. Save metadata such as uploader, timestamp, source system, file name, and a checksum (to detect duplicates and ensure integrity). This becomes invaluable for auditability and debugging.

Run fast pre-checks immediately and fail early when needed:

If a pre-check fails, return a clear message and show what to fix. The goal is to block truly bad files quickly—without blocking valid but imperfect data that can be mapped and cleaned in later steps.

Most import failures happen because the file’s headers don’t match your app’s fields. A clear column mapping step turns “messy CSV” into predictable input and saves users from trial-and-error.

Show a simple table: Source column → Destination field. Autodetect likely matches (case-insensitive header matching, synonyms like “E-mail” → email), but always let users override.

Include a few quality-of-life touches:

If customers import the same format every week, make it one click. Let them save templates scoped to:

When a new file is uploaded, suggest a template based on column overlap. Also support versioning so users can update a template without breaking older runs.

Add lightweight transforms users can apply per mapped field:

Keep transforms explicit in the UI (“Applied: Trim → Parse Date”) so the output is explainable.

Before processing the full file, show a preview of mapped results for (say) 20 rows. Display the original value, the transformed value, and warnings (like “Could not parse date”). This is where users catch issues early.

Ask users to choose a key field (email, external_id, SKU) and explain what happens on duplicates. Even if you handle upserts later, this step sets expectations: you can warn about duplicate keys in the file and suggest which record “wins” (first, last, or error).

Validation is the difference between a “file uploader” and an import feature people can trust. The goal isn’t to be strict for its own sake—it’s to prevent bad data from spreading while giving users clear, actionable feedback.

Treat validation as three distinct checks, each with a different purpose:

email a string?”, “Is amount a number?”, “Is customer_id present?” This is fast and can run immediately after parsing.country=US, state is required”, “end_date must be after start_date”, “Plan name must exist in this workspace.” These often require context (other columns or database lookups).Keeping these layers separate makes the system easier to extend and easier to explain in the UI.

Decide early whether an import should:

You can also support both: strict as default, with an “Allow partial import” option for admins.

Every error should answer: what happened, where, and how to fix it.

Example: “Row 42, Column ‘Start Date’: must be a valid date in YYYY-MM-DD format.”

Differentiate:

Users rarely fix everything in one pass. Make re-uploads painless by keeping validation results tied to an import attempt and allowing the user to re-upload a corrected file. Pair this with downloadable error reports (covered later) so they can resolve issues in bulk.

A practical approach is a hybrid:

This keeps validation flexible without turning it into a hard-to-debug “settings maze.”

Imports tend to fail for boring reasons: slow databases, file spikes at peak time, or a single “bad” row that blocks the whole batch. Reliability is mostly about moving heavy work off the request/response path and making every step safe to run again.

Run parsing, validation, and writes in background jobs (queues/workers) so uploads don’t hit web timeouts. This also lets you scale workers independently when customers start importing bigger spreadsheets.

A practical pattern is to split work into chunks (for example 1,000 rows per job). One “parent” import job schedules chunk jobs, aggregates results, and updates progress.

Model the import as a state machine so the UI and ops team always know what’s happening:

Store timestamps and attempt counts per state transition so you can answer “when did it start?” and “how many retries?” without digging through logs.

Show measurable progress: rows processed, rows remaining, and errors found so far. If you can estimate throughput, add a rough ETA—but prefer “~3 min” over precise countdowns.

Retries should never create duplicates or double-apply updates. Common techniques:

Rate-limit concurrent imports per workspace and throttle write-heavy steps (e.g., max N rows/sec) to avoid overwhelming the database and degrading the experience for other users.

If people can’t understand what went wrong, they’ll retry the same file until they give up. Treat every import as a first-class “run” with a clear paper trail and actionable errors.

Start by creating an import run entity the moment a file is submitted. This record should capture the essentials:

This becomes your import history screen: a simple list of runs with status, counts, and a “view details” page.

Application logs are great for engineers, but users need queryable errors. Store errors as structured records tied to the import run, ideally at both levels:

With this structure you can power fast filtering and aggregate insights like “Top 3 error types this week.”

In the run details page, provide filters by type, column, and severity, plus a search box (e.g., “email”). Then offer a downloadable CSV error report that includes the original row plus extra columns like error_columns and error_message, with clear guidance such as “Fix date format to YYYY-MM-DD.”

A “dry run” validates everything using the same mapping and rules, but doesn’t write data. It’s ideal for first-time imports and lets users iterate safely before they commit changes.

Imports feel “done” once rows land in your database—but the long-term cost is usually in messy updates, duplicates, and unclear change history. This section is about designing your data model so imports are predictable, reversible, and explainable.

Start by defining how an imported row maps to your domain model. For each entity, decide whether the import can:

This decision should be explicit in the import setup UI and stored with the import job so the behavior is repeatable.

If you support “create or update,” you need stable upsert keys—fields that identify the same record every time. Common choices:

external_id (best when coming from another system)account_id + sku)Define collision handling rules: what happens if two rows share the same key, or if a key matches multiple records? Good defaults are “fail the row with a clear error” or “last row wins,” but choose deliberately.

Use transactions where they protect consistency (e.g., creating a parent and its children). Avoid one giant transaction for a 200k-row file; it can lock tables and make retries painful. Prefer chunked writes (e.g., 500–2,000 rows per batch) with idempotent upserts.

Imports should respect relationships: if a row references a parent record (like a Company), either require it to exist or create it in a controlled step. Failing early with “missing parent” errors prevents half-connected data.

Add audit logs for import-driven changes: who triggered the import, when, source file, and a per-record summary of what changed (old vs new). This makes support easier, builds user trust, and simplifies rollbacks.

Exports look simple until customers try to download “everything” right before a deadline. A scalable export system should handle large datasets without slowing down your app or producing inconsistent files.

Start with three options:

Incremental exports are especially helpful for integrations and reduce load compared to repeated full dumps.

Whatever you choose, keep consistent headers and stable column order so downstream processes don’t break.

Large exports should not load all rows into memory. Use pagination/streaming to write rows as you fetch them. This prevents timeouts and keeps your web app responsive.

For large datasets, generate exports in a background job and notify the user when it’s ready. A common pattern is:

This pairs well with your background jobs for imports and with the same “run history + downloadable artifact” pattern you use for error reports.

Exports often get audited. Always include:

These details reduce confusion and support reliable reconciliation.

Imports and exports are powerful features because they can move a lot of data quickly. That also makes them a common place for security bugs: one overly-permissive role, one leaked file URL, or one log line that accidentally includes personal data.

Start with the same authentication you use across the app—don’t create a “special” auth path just for imports.

If your users work in a browser, session-based auth (plus optional SSO/SAML) usually fits best. If imports/exports are automated (nightly jobs, integration partners), consider API keys or OAuth tokens with clear scoping and rotation.

A practical rule: the import UI and the import API should both enforce the same permissions, even if they’re used by different audiences.

Treat import/export capabilities as explicit privileges. Common roles include:

Make “download files” a separate permission. A lot of sensitive leaks happen when someone can view an import run and the system assumes they can also download the original spreadsheet.

Also consider row-level or tenant-level boundaries: a user should only import/export data for the account (or workspace) they belong to.

For stored files (uploads, generated error CSVs, export archives), use private object storage and short-lived download links. Encrypt at rest when required by your compliance needs, and be consistent: the original upload, the processed staging file, and any generated reports should all follow the same rules.

Be careful with logs. Redact sensitive fields (emails, phone numbers, IDs, addresses) and never log raw rows by default. When debugging is necessary, gate “verbose row logging” behind admin-only settings and ensure it expires.

Treat every upload as untrusted input:

Also validate structure early: reject obviously malformed files before they reach background jobs, and provide a clear message to the user about what’s wrong.

Record events you’d want during an investigation: who uploaded a file, who started an import, who downloaded an export, permission changes, and failed access attempts.

Audit entries should include actor, timestamp, workspace/tenant, and the object affected (import run ID, export ID), without storing sensitive row data. This pairs well with your import history UI and helps you answer “who changed what, and when?” quickly.

If imports and exports touch customer data, you’ll eventually get edge cases: weird encodings, merged cells, half-filled rows, duplicates, and “it worked yesterday” mysteries. Operability is what keeps those issues from turning into support nightmares.

Start with focused tests around the most failure-prone parts: parsing, mapping, and validation.

Then add at least one end-to-end test for the complete flow: upload → background processing → report generation. These tests catch contract mismatches between UI, API, and workers (for example, a job payload missing the mapping configuration).

Track signals that reflect user impact:

Wire alerts to symptoms (increased failures, growing queue depth) rather than every exception.

Give internal teams a small admin surface to re-run jobs, cancel stuck imports, and inspect failures (input file metadata, mapping used, error summary, and a link to logs/traces).

For users, reduce preventable errors with inline tips, downloadable sample templates, and clear next steps in error screens. Keep a central help page and link it from the import UI (for example: /docs).

Shipping an import/export system isn’t just “push to production.” Treat it like a product feature with safe defaults, clear recovery paths, and room to evolve.

Set up separate dev/staging/prod environments with isolated databases and separate object storage buckets (or prefixes) for uploaded files and generated exports. Use different encryption keys and credentials per environment, and make sure background job workers point to the right queues.

Staging should mirror production: same job concurrency, timeouts, and file size limits. That’s where you can validate performance and permissions without risking real customer data.

Imports tend to “live forever” because customers keep old spreadsheets around. Use database migrations as usual, but also version your import templates (and mapping presets) so a schema change doesn’t break last quarter’s CSV.

A practical approach is to store template_version with each import run and keep compatibility code for older versions until you can deprecate them.

Use feature flags to ship changes safely:

Flags let you test with internal users or a small customer cohort before turning features on broadly.

Document how support should investigate failures using your import history, job IDs, and logs. A simple checklist helps: confirm template version, review first failing row, check storage access, then inspect worker logs. Link this from your internal runbook and, where appropriate, your admin UI (e.g., /admin/imports).

Once the core workflow is stable, extend it beyond uploads:

These upgrades reduce manual work and make your data import web app feel native in customers’ existing processes.

If you’re building this as a product feature and want to shorten the “first usable version” timeline, consider using Koder.ai to prototype the import wizard, job status pages, and run history screens end-to-end, then export the source code for a conventional engineering workflow. That approach can be especially practical when the goal is reliability and iteration speed (not bespoke UI perfection on day one).”

Start by clarifying who is importing/exporting (admins, operators, customers) and your top use cases (onboarding bulk load, periodic sync, one-off exports).

Write down day-one constraints:

These decisions drive architecture, UI complexity, and support load.

Use synchronous processing when files are small and validation + writes reliably finish within your web request timeouts.

Use background jobs when:

A common pattern is: upload → enqueue → show run status/progress → notify on completion.

Store both, for different reasons:

Keep the raw upload immutable, and tie it to an import run record.

Build a preview step that detects headers and parses a small sample (e.g., 20–100 rows) before committing anything.

Handle common variability:

Fail fast on true blockers (unreadable file, missing required columns), but don’t reject data that can be mapped or transformed later.

Use a simple mapping table: Source column → Destination field.

Best practices:

Always show a mapped preview so users can catch mistakes before processing the full file.

Keep transformations lightweight and explicit so users can predict results:

ACTIVE)Show “original → transformed” in the preview, and surface warnings when a transform can’t be applied.

Separate validation into layers:

In the UI, provide actionable messages with row/column references (e.g., “Row 42, Start Date: must be YYYY-MM-DD”).

Decide whether imports are (fail whole file) or (accept valid rows), and consider offering both for admins.

Make processing retry-safe:

import_id + row_number or row hash)external_id) over “insert always”Create an import run record as soon as a file is submitted, and store structured, queryable errors—not just logs.

Useful error-reporting features:

This reduces “retry until it works” behavior and support tickets.

Treat import/export as privileged actions:

If you handle PII, decide retention and deletion rules early so you don’t accumulate sensitive files indefinitely.

Also throttle concurrent imports per workspace to protect the database and other users.