Sep 05, 2025·8 min

Web Workers vs Service Workers: what they are and why

Learn what Web Workers and Service Workers are, how they differ, and when to use each for faster pages, background tasks, caching, and offline support.

Learn what Web Workers and Service Workers are, how they differ, and when to use each for faster pages, background tasks, caching, and offline support.

Browsers run most of your JavaScript on the main thread—the same place that handles user input, animations, and painting the page. When heavy work happens there (parsing big data, image processing, complex calculations), the UI can stutter or “freeze.” Workers exist to move certain tasks off the main thread or out of the page’s direct control, so your app stays responsive.

If your page is busy doing a 200ms computation, the browser can’t smoothly scroll, respond to clicks, or keep animations at 60fps. Workers help by letting you do background work while the main thread focuses on the interface.

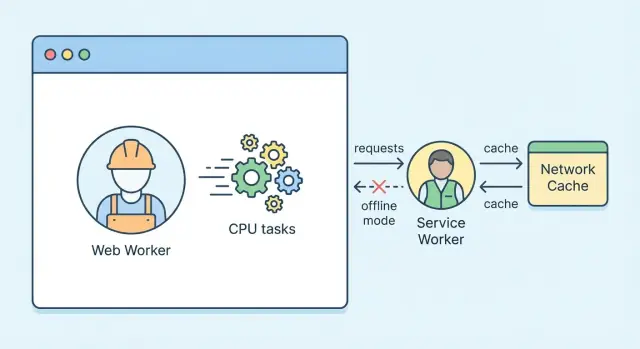

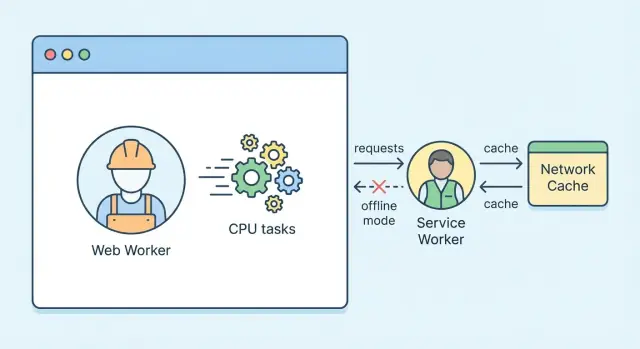

A Web Worker is a background JavaScript thread you create from a page. It’s best for CPU-heavy tasks that would otherwise block the UI.

A Service Worker is a special kind of worker that sits between your web app and the network. It can intercept requests, cache responses, and enable features like offline support and push notifications.

Think of a Web Worker as a helper doing calculations in another room. You send it a message, it works, and it messages back.

Think of a Service Worker as a gatekeeper at the front door. Requests for pages, scripts, and API calls pass by it, and it can decide whether to fetch from the network, serve from cache, or respond in a custom way.

By the end, you’ll know:

postMessage) fits into the worker model, and why the Cache Storage API matters for offlineThis overview sets the “why” and the mental model—next we’ll dive into how each worker type behaves and where it fits in real projects.

When you open a web page, most of what you “feel” happens on the main thread. It’s responsible for drawing pixels (rendering), reacting to taps and clicks (input), and running a lot of JavaScript.

Because rendering, input handling, and JavaScript often take turns on the same thread, one slow task can make everything else wait. That’s why performance problems tend to show up as responsiveness problems, not just “slow code.”

What “blocking” feels like to users:

JavaScript has many asynchronous APIs—fetch(), timers, events—that help you avoid waiting idly. But async doesn’t magically make heavy work happen at the same time as rendering.

If you do expensive computation (image processing, big JSON crunching, crypto, complex filtering) on the main thread, it still competes with UI updates. “Async” can delay when it runs, but it may still run on the same main thread and still cause jank when it executes.

Workers exist so browsers can keep the page responsive while still doing meaningful work.

In short: workers are a way to protect the main thread so your app can stay interactive while doing real work in the background.

A Web Worker is a way to run JavaScript off the main thread. Instead of competing with UI work (rendering, scrolling, responding to clicks), a worker runs in its own background thread so heavy tasks can finish without making the page feel “stuck.”

Think of it as: the page stays focused on user interaction, while the worker handles CPU-heavy work like parsing a big file, crunching numbers, or preparing data for charts.

A Web Worker runs in a separate thread with its own global scope. It still has access to many web APIs (timers, fetch in many browsers, crypto, etc.), but it’s intentionally isolated from the page.

There are a couple of common flavors:

If you’ve never used workers before, most examples you’ll see are dedicated workers.

Workers don’t directly call functions in your page. Instead, communication happens by sending messages:

postMessage().postMessage() as well.For large binary data, you can often improve performance by transferring ownership of an ArrayBuffer (so it isn’t copied), which keeps message passing fast.

Because a worker is isolated, there are a few key constraints:

window or document. Workers run under self (a worker global scope), and APIs available can differ from the main page.Used well, a Web Worker is one of the simplest ways to improve main thread performance without changing what your app does—just where the expensive work happens.

Web Workers are a great fit when your page feels “stuck” because JavaScript is doing too much work on the main thread. The main thread is also responsible for user interactions and rendering, so heavy tasks there can cause jank, delayed clicks, and frozen scrolling.

Use a Web Worker when you have CPU-heavy work that doesn’t need direct access to the DOM:

A practical example: if you receive a large JSON payload and parsing it causes the UI to stutter, move parsing into a worker, then send back the result.

Communication with a worker happens through postMessage. For large binary data, prefer transferable objects (like ArrayBuffer) so the browser can hand memory ownership to the worker instead of copying it.

// main thread

worker.postMessage(buffer, [buffer]); // transfers the ArrayBuffer

This is especially useful for audio buffers, image bytes, or other large chunks of data.

Workers have overhead: extra files, message passing, and a different debugging flow. Skip them when:

postMessage ping-pong can erase the benefit.If a task can cause a noticeable pause (often ~50ms+) and can be expressed as “input → compute → output” without DOM access, a Web Worker is usually worth it. If it’s mostly UI updates, keep it on the main thread and optimize there instead.

A Service Worker is a special kind of JavaScript file that runs in the background of the browser and acts like a programmable network layer for your site. Instead of running on the page itself, it sits between your web app and the network, letting you decide what happens when the app requests resources (HTML, CSS, API calls, images).

A Service Worker has a lifecycle that’s separate from any single tab:

Because it can be stopped and restarted at any time, treat it like an event-driven script: do work quickly, store state in persistent storage, and avoid assuming it’s always running.

Service Workers are restricted to the same origin (same domain/protocol/port) and only control pages under their scope—usually the folder where the worker file is served (and below). They also require HTTPS (except localhost) because they can affect network requests.

A Service Worker is mainly used to sit between your web app and the network. It can decide when to use the network, when to use cached data, and when to do a bit of work in the background—without blocking the page.

The most common job is enabling offline or “poor connection” experiences by caching assets and responses.

A few practical caching strategies you’ll see:

This is usually implemented with the Cache Storage API and fetch event handling.

Service Workers can improve perceived speed on return visits by:

The result is fewer network requests, faster start-up, and more consistent performance on flaky connections.

Service Workers can power background capabilities such as push notifications and background sync (support varies by browser and platform). That means you can notify users or retry a failed request later—even if the page isn’t currently open.

If you’re building a progressive web app, Service Workers are a core piece behind:

If you remember only one thing: Web Workers help your page do heavy work without freezing the UI, while Service Workers help your app control network requests and behave like an installable app (PWA).

A Web Worker is for CPU-heavy tasks—parsing large data, generating thumbnails, crunching numbers—so the main thread stays responsive.

A Service Worker is for request handling and app lifecycle tasks—offline support, caching strategies, background sync, and push notifications. It can sit between your app and the network.

A Web Worker is typically tied to a page/tab. When the page goes away, the worker usually goes away too (unless you’re using special cases like SharedWorker).

A Service Worker is event-driven. The browser can start it to handle an event (like a fetch or push), then stop it when it’s idle. That means it can run even when no tab is currently open, as long as an event wakes it.

A Web Worker cannot intercept network requests made by the page. It can fetch() data, but it can’t rewrite, cache, or serve responses for other parts of your site.

A Service Worker can intercept network requests (via the fetch event), decide whether to go to the network, respond from cache, or return a fallback.

A Web Worker doesn’t manage HTTP caching for your app.

A Service Worker commonly uses the Cache Storage API to store and serve request/response pairs—this is the foundation for offline caching and “instant” repeat loads.

Getting a worker running is mostly about where it runs from and how it’s loaded. Web Workers are created directly by a page script. Service Workers are installed by the browser and sit “in front” of network requests for your site.

A Web Worker starts life when your page creates one. You point to a separate JavaScript file, then communicate via postMessage.

// main.js (running on the page)

const worker = new Worker('/workers/resize-worker.js', { type: 'module' });

worker.postMessage({ action: 'start', payload: { /* ... */ } });

worker.onmessage = {

.(, event.);

};

A good mental model: the worker file is just another script URL your page can fetch, but it runs off the main thread.

Service Workers must be registered from a page that your user visits:

// main.js

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register('/sw.js');

}

After registration, the browser handles the install/activate lifecycle. Your sw.js can listen for events like install, activate, and fetch.

Service Workers can intercept network requests and cache responses. If registration were allowed over HTTP, a network attacker could swap in a malicious sw.js and effectively control future visits. HTTPS (or http://localhost for development) protects the script and the traffic it can influence.

Browsers cache and update workers differently than normal page scripts. Plan for updates:

sw.js/worker bundle).If you want a smoother rollout strategy later, see /blog/debugging-workers for testing habits that catch update edge cases early.

Workers fail in different ways than “normal” page JavaScript: they run in separate contexts, have their own console, and can be restarted by the browser. A solid debugging routine saves hours.

Open DevTools and look for worker-specific targets. In Chrome/Edge, you’ll often see workers listed under Sources (or via the “Dedicated worker” entry) and in the Console context selector.

Use the same tools you’d use on the main thread:

onmessage handlers and long-running functions.If messages seem “lost,” inspect both sides: verify you’re calling worker.postMessage(...), that the worker has self.onmessage = ..., and that your message shape matches.

Service Workers are best debugged in the Application panel:

Also watch the Console for install/activate/fetch errors—these often explain why caching or offline behavior isn’t working.

Caching issues are the #1 time sink: caching the wrong files (or too aggressively) can keep old HTML/JS around. During tests, try hard reload behavior and confirm what’s actually served from the cache.

For realistic testing, use DevTools to:

If you’re iterating quickly on a PWA, it can help to generate a clean baseline app (with a predictable Service Worker and build output) and then refine caching strategies from there. Platforms like Koder.ai can be useful for this kind of experimentation: you can prototype a React-based web app from a chat prompt, export the source code, and then tweak your worker setup and caching rules with a tighter feedback loop.

Workers can make apps smoother and more capable, but they also change where code runs and what it can access. A quick check on security, privacy, and performance will save you from surprising bugs—and unhappy users.

Both Web Workers and Service Workers are restricted by the same-origin policy: they can only directly interact with resources from the same scheme/host/port (unless the server explicitly allows cross-origin access via CORS). This prevents a worker from quietly pulling data from another site and mixing it into your app.

Service Workers have extra guardrails: they generally require HTTPS (or localhost in development) because they can intercept network requests. Treat them like privileged code: keep dependencies minimal, avoid dynamic code loading, and version your caching logic carefully so old caches don’t keep serving outdated files.

Background features should feel predictable. Push notifications are powerful, but permission prompts are easy to abuse.

Ask for permission only when there’s a clear benefit (for example, after a user enables alerts in settings), and explain what they’ll receive. If you sync or prefetch data in the background, communicate it in plain language—users notice unexpected network activity or notifications.

Workers aren’t “free performance.” Overusing them can backfire:

postMessage calls (especially with large objects) can become a bottleneck. Prefer batching and using transferable objects when appropriate.Not every browser supports every capability (or users may block permissions). Feature-detect and degrade cleanly:

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

// register service worker

} else {

// continue without offline features

}

The goal: core functionality should still work, with “nice-to-haves” (offline, push, heavy computations) layered on when available.

Web Workers and Service Workers solve different problems, so they pair well when an app needs both heavy computation and fast, reliable loading. A good mental model is: Web Worker = compute, Service Worker = network + caching, main thread = UI.

Say your app lets users edit photos (resize, filters, background removal) and view a gallery later without a connection.

This “compute then cache” approach keeps responsibilities clear: the worker produces outputs, and the service worker decides how to store and serve them.

For apps with feeds, forms, or field data:

Even without full background sync, a service worker still improves perceived speed by serving cached responses while the app updates in the background.

Avoid mixing roles:

postMessage).No. A Service Worker runs in the background, separate from any page tab, and it doesn’t have direct access to the DOM (the page’s HTML elements).

That separation is intentional: Service Workers are designed to keep working even when no page is open (for example, to respond to a push event or to serve cached files). Because there may be no active document to manipulate, the browser keeps it isolated.

If a Service Worker needs to affect what a user sees, it communicates with pages via messaging (for example, postMessage) so the page can update the UI.

No. Web Workers and Service Workers are independent features.

You can use either one alone, or both together if your app needs both background networking and background computation.

In modern browsers, Web Workers are widely supported and usually the safer “baseline” choice.

Service Workers are also widely supported in current versions of major browsers, but there are more requirements and edge cases:

localhost for development).If broad compatibility matters, treat Service Worker features as progressive enhancement: build a good core experience first, then add offline/push where available.

Not automatically.

The real gains come from using the right worker for the right bottleneck, and measuring before and after.

Use a Web Worker when you have CPU-heavy work that can be expressed as input → compute → output and doesn’t need the DOM.

Good fits include parsing/transforming large payloads, compression, crypto, image/audio processing, and complex filtering. If the work is mostly UI updates or frequent DOM reads/writes, a worker won’t help (and can’t access the DOM anyway).

Use a Service Worker when you need network control: offline support, caching strategies, faster repeat visits, request routing, and (where supported) push/background sync.

If your problem is “the UI freezes while computing,” that’s a Web Worker problem. If your problem is “loading is slow/offline is broken,” that’s a Service Worker problem.

No. Web Workers and Service Workers are independent.

You can use either alone, or combine them when you need both compute and offline/network features.

Mostly scope and lifetime.

fetch) even when no page is open, then shut down when idle.No. Web Workers don’t have window/document access.

If you need to affect the UI, send data back to the main thread via postMessage(), then update the DOM in your page code. Keep the worker focused on pure computation.

No. Service Workers don’t have DOM access.

To influence what the user sees, communicate with controlled pages via messaging (for example using the Clients API + postMessage()), and let the page update the UI.

Use postMessage() on both sides.

worker.postMessage(data)self.postMessage(result)For large binary data, prefer transferables (like ArrayBuffer) to avoid copying:

Service Workers sit between your app and the network and can respond to requests using the Cache Storage API.

Common strategies:

Pick a strategy per resource type (app shell vs API data), not one global rule.

Yes, but keep responsibilities clear.

A common pattern is:

This avoids mixing UI logic into background contexts and keeps performance predictable.

Use the right DevTools surface for each.

onmessage, and profile to confirm the main thread stays responsive.When debugging caching bugs, always verify what’s actually served (network vs cache) and test offline/throttling.

worker.postMessage(buffer, [buffer]);