Oct 24, 2025·8 min

What It Really Means When AI “Builds an App” (and What It Doesn’t)

A practical guide to what AI app builders can generate, where humans still decide, and how to scope, budget, and ship an app without hype.

A practical guide to what AI app builders can generate, where humans still decide, and how to scope, budget, and ship an app without hype.

When someone says “AI is building an app,” they usually don’t mean a robot independently invents a product, writes perfect code, ships it to the App Store, and supports customers afterward.

In plain English, “AI building an app” typically means using AI tools to speed up parts of app creation—like drafting screens, generating code snippets, suggesting database tables, writing tests, or helping troubleshoot errors. The AI is more like a very fast assistant than a full replacement for a product team.

It’s confusing because it can describe very different setups:

All of these involve AI, but they produce different levels of control, quality, and long-term maintainability.

You’ll learn what AI can realistically help with, where it tends to make mistakes, and how to scope your idea so you don’t confuse a quick demo with a shippable product.

What this article won’t promise: that you can type one sentence and receive a secure, compliant, polished app that’s ready for real users.

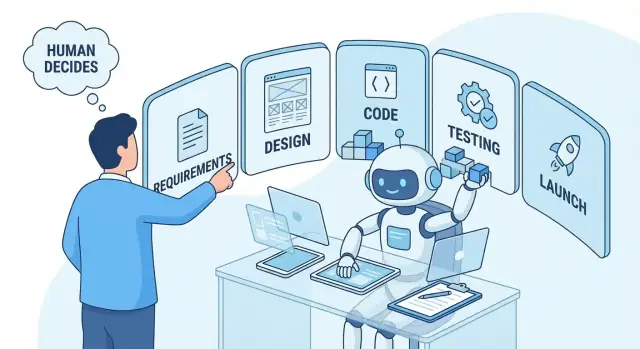

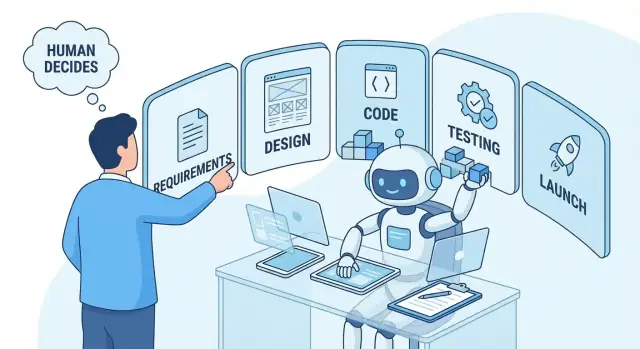

No matter how much AI you use, most apps still follow the same arc:

AI can accelerate several of these steps—but it doesn’t eliminate them.

When someone says “AI built my app,” they might mean anything from “AI suggested a neat concept” to “we shipped a working product to real users.” Those are very different outcomes—and mixing them up is where expectations get crushed.

Sometimes “build” just means the AI generated:

This can be genuinely useful, especially early on. But it’s closer to brainstorming and documentation than development.

Other times, “build” means the AI wrote code: a form, an API endpoint, a database query, a UI component, or a quick script.

That can save time, but it’s not the same as having a coherent application. Code still needs to be reviewed, tested, and integrated into a real project. “AI-generated code” often looks finished while hiding issues like missing error handling, security gaps, or inconsistent structure.

With an AI app builder (or a no‑code platform with AI features), “build” may mean the tool assembled templates and connected services for you.

This can produce a working demo quickly. The tradeoff is that you’re building inside someone else’s constraints: limited customization, data model restrictions, performance ceilings, and platform lock‑in.

Shipping includes all the unglamorous parts: authentication, data storage, payments, privacy policy, analytics, monitoring, bug fixes, device/browser compatibility, app store submission, and ongoing maintenance.

This is the key concept: AI is a powerful tool, but it isn’t an accountable owner. If something breaks, leaks data, or fails compliance checks, AI won’t be responsible—you (and your team) will.

A prototype can impress in minutes. A production-ready app must survive real users, real edge cases, and real security expectations. Many “AI built my app” stories are really “AI helped me make a convincing demo.”

AI doesn’t “understand” your business the way a teammate would. It predicts useful outputs from patterns in its training data plus the details you provide. When your prompts are specific, AI can be excellent at producing first drafts quickly—and helping you iterate.

You can expect AI to produce:

The key is that these are starting points. You still need someone to validate them against real users and real constraints.

AI shines when the work is repetitive, well-scoped, and easy to verify. It can help you:

Even when the output looks polished, AI isn’t bringing real user insight. It doesn’t know your customers, your legal obligations, your internal systems, or what will be maintainable six months from now—unless you provide that context and someone checks the results.

AI can generate screens, APIs, and even a working demo quickly—but a demo is not the same thing as a production app.

A production-ready app needs security, reliability, monitoring, and maintainability. That includes things like safe authentication, rate limiting, secrets management, backups, logging, alerting, and a clear upgrade path when dependencies change. AI can suggest pieces of this, but it won’t consistently design (and validate) a complete, defensible setup end-to-end.

Most AI-generated apps look great on the “happy path”: clean sample data, perfect network, a single user role, and no unexpected inputs. Real users do the opposite. They sign up with weird names, paste huge text, upload the wrong files, lose connection mid-checkout, and trigger rare timing issues.

Handling these edge cases requires decisions about validation rules, user messaging, retries, data cleanup, and what to do when third-party services fail. AI can help brainstorm scenarios, but it can’t reliably predict your actual users and operational reality.

When the app has a bug, who fixes it? When there’s an outage, who gets paged? When a payment fails or data is wrong, who investigates and supports users? AI can produce code, but it doesn’t own the consequences. Someone still needs to be responsible for debugging, incident response, and ongoing support.

AI can draft policies, but it cannot decide what you’re legally required to do—or what risk you’re willing to accept. Data retention, consent, access controls, and handling sensitive information (health, payments, children’s data) require deliberate choices, often with professional advice.

AI can speed up app development, but it doesn’t remove the need for judgment. The most important calls—what to build, for whom, and what “good” looks like—still belong to humans. If you delegate these decisions to an AI, you often get a product that’s technically “done” but strategically wrong.

An AI can help you write a first pass of user stories, screens, or an MVP scope. But it can’t know your real business constraints: deadlines, budget, legal rules, team skills, or what you’re willing to trade off.

Humans decide what matters most (speed vs quality, growth vs revenue, simplicity vs features) and what must not happen (storing sensitive data, relying on a third-party API, building something that can’t be supported later).

AI can generate UI ideas, copy variations, and even component suggestions. The human decision is whether the design is understandable for your users and consistent with your brand.

Usability is where “looks fine” can still fail: button placement, accessibility, error messages, and the overall flow. Humans also decide what the product should feel like—trustworthy, playful, premium—because that’s not just a layout problem.

AI-generated code can be a great accelerator, especially for common patterns (forms, CRUD, simple APIs). But humans choose the architecture: where logic lives, how data moves, how to scale, how to log, and how to recover from failures.

This is also where long-term cost is set. Decisions about dependencies, security, and maintainability usually can’t be “fixed later” without rework.

AI can suggest test cases, edge conditions, and sample automated tests. Humans still need to confirm the app works in the messy real world: slow networks, odd device sizes, partial permissions, unexpected user behavior, and “it works but feels broken” moments.

AI can draft release notes, create a launch checklist, and remind you of common store requirements. But humans are accountable for approvals, app store submissions, privacy policies, and compliance.

When something goes wrong after launch, it’s not the AI answering customer emails or deciding whether to roll back a release. That responsibility stays firmly human.

AI output quality is tightly tied to input quality. A “clear prompt” isn’t fancy wording—it’s clear requirements: what you’re building, for whom, and what rules must always be true.

If you can’t describe your goal, users, and constraints, the model will fill the gaps with guesses. That’s when you get code that looks plausible but doesn’t match what you actually need.

Start by writing down:

Use this as a starting point:

Who: [primary user]

What: build [feature/screen/API] that lets the user [action]

Why: so they can [outcome], measured by [metric]

Constraints: [platform/stack], [must/must not], [privacy/security], [performance], [deadline]

Acceptance criteria: [bullet list of pass/fail checks]

Vague: “Make a booking app.”

Measurable: “Customers can book a 30‑minute slot. The system prevents double-booking. Admins can block out dates. Confirmation email is sent within 1 minute. If payment fails, the booking is not created.”

Missing edge cases (cancellations, time zones, retries), unclear scope (“full app” vs one flow), and no acceptance criteria (“works well” isn’t testable). When you add pass/fail criteria, AI becomes much more useful—and your team spends less time redoing work.

When someone says “AI built my app,” they could mean three very different paths: an AI app builder platform, a no‑code tool, or custom development where AI helps write code. The right choice depends less on hype and more on what you need to ship—and what you need to own.

These tools generate screens, simple databases, and basic logic from a description.

Best fit: fast prototypes, internal tools, simple MVPs where you can accept platform limits.

Tradeoffs: customization can hit a ceiling quickly (complex permissions, unusual workflows, integrations). You’re also usually tied to the platform’s hosting and data model.

A practical middle ground is a “vibe-coding” platform like Koder.ai, where you build through chat but still end up with a real application structure (web apps commonly built with React; backends often using Go and PostgreSQL; and Flutter for mobile). The important question isn’t whether AI can generate something—it’s whether you can iterate, test, and own what gets generated (including exporting source code, rolling back changes, and deploying safely).

No‑code tools give you more explicit control than “prompt-only” builders: you assemble pages, workflows, and automations yourself.

Best fit: business apps with standard patterns (forms, approvals, dashboards), and teams that want speed without writing code.

Tradeoffs: advanced features often require workarounds, and performance can suffer at scale. Some platforms allow exporting parts of your data; most don’t let you fully “take the app with you.”

Here you (or a developer) build with a normal codebase, using AI to speed up scaffolding, UI generation, tests, and documentation.

Best fit: products that need unique UX, long-term flexibility, serious security/compliance, or complex integrations.

Tradeoffs: higher upfront cost and more project management, but you own the code and can change hosting, database, and vendors.

If you build on a platform, moving off it later can mean rebuilding from scratch—even if you can export data. With custom code, switching vendors is usually a migration, not a rewrite.

If “owning the code” matters, look specifically for platforms that support source code export, sane deployment options, and operational controls like snapshots and rollback (so experimentation doesn’t turn into risk).

When someone says “AI built my app,” it helps to ask: which parts of the app? Most real apps are a bundle of systems working together, and the “one-click” output is often just the most visible layer.

Most products—whether mobile, web, or both—include:

Many AI app builder demos generate a UI and some sample data, but skip the hard product questions:

A booking app usually needs: service listings, staff schedules, availability rules, booking flow, cancellation policy, customer notifications, and an admin panel to manage everything. It also needs security basics like rate limiting and input validation, even if the UI looks finished.

Most apps quickly require external services:

If you can name these components up front, you’ll scope more accurately—and you’ll know what you’re actually asking AI to generate versus what still needs design and decisions.

AI can speed up app development, but it also makes it easier to ship problems faster. The main risks cluster around quality, security, and privacy—especially when AI-generated code is copied into a real product without a careful review.

AI output can look polished while hiding basics that production apps need:

These issues aren’t just cosmetic—they turn into bugs, support tickets, and rewrites.

Copying generated code without review can introduce common vulnerabilities: unsafe database queries, missing authorization checks, insecure file uploads, and accidental logging of personal data. Another frequent problem is secrets ending up in code—API keys, service credentials, or tokens that a model suggested as placeholders and someone forgot to remove.

Practical safeguard: treat AI output like code from an unknown source. Require human code review, run automated tests, and add secret scanning in your repo and CI pipeline.

Many tools send prompts (and sometimes snippets) to third-party services. If you paste customer records, internal URLs, private keys, or proprietary logic into prompts, you may be disclosing sensitive information.

Practical safeguard: share the minimum. Use synthetic data, redact identifiers, and check your tool’s settings for data retention and training opt-outs.

Generated code and content can raise licensing questions, especially if it closely mirrors existing open-source patterns or includes copied snippets. Teams should still follow attribution requirements and keep a record of sources when AI output is based on referenced material.

Practical safeguard: use dependency/license scanners, and set a policy for when legal review is required (for example, before shipping an MVP to production).

A useful way to think about “AI building an app” is: you still run the project, but AI helps you do the writing, organizing, and first drafts faster—then you verify and ship.

If you’re using a chat-first builder like Koder.ai, this workflow still applies: treat each AI-generated change as a proposal, use planning mode (or an equivalent) to clarify scope first, and lean on snapshots/rollback so experiments don’t become production regressions.

Start by defining the smallest version that proves the idea.

Ask AI to draft a one-page MVP brief from your notes, then edit it yourself until it’s unambiguous.

For each feature, write acceptance criteria so everyone agrees what “done” is. AI is great at generating first drafts.

Example:

Create a “Not in MVP” list on day one. This prevents scope creep from sneaking in disguised as “just one more thing.” AI can suggest common cuts: social login, multi-language, admin dashboards, advanced analytics, payments—whatever isn’t required to hit your success metric.

The point is consistency: AI drafts, humans verify. You keep ownership of priorities, correctness, and trade-offs.

“AI building an app” can reduce some labor, but it doesn’t remove the work that determines real cost: deciding what to build, validating it, integrating it with real systems, and keeping it running.

Most budgets aren’t defined by “how many screens,” but by what those screens must do.

Even a small app has recurring work:

A helpful mental model: building the first version is often the start of spending, not the end.

AI can save time on drafting: scaffolding screens, generating boilerplate code, writing basic tests, and producing first-pass documentation.

But AI rarely eliminates time spent on:

So the budget may shift from “typing code” to “reviewing, correcting, and validating.” That can be faster—but it’s not free.

If you’re comparing tools, include operational features in the cost conversation—deployment/hosting, custom domains, and the ability to snapshot and roll back. These don’t sound exciting, but they strongly affect real maintenance effort.

Use this quick worksheet before you estimate costs:

| Step | Write down | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Top 3 user actions (e.g., sign up, create item, pay) + must-have platforms (web/iOS/Android) | A clear MVP definition |

| Effort | For each action: data needed, screens, integrations, permissions | Rough size: Small / Medium / Large |

| Timeline | Who builds it (you, no-code, dev team) + review/testing time | Weeks, not days |

| Risk | Security/privacy needs, external dependencies, “unknowns” | What to de-risk first (prototype, spike, pilot) |

If you can’t fill in the Scope row in plain language, any cost estimate—AI-assisted or not—will be a guess.

AI can get you surprisingly far—especially for early prototypes and simple internal tools. Use this checklist to decide whether an AI app builder (or AI-assisted development) is enough, or whether you’ll quickly run into “needs an expert” territory.

If you can answer these clearly, AI tools will usually produce something usable faster.

If you’re missing most of the above, start with clarifying requirements first—AI prompts only work when your inputs are specific.

AI tools can still assist, but you’ll want a human who can design, review, and own the risk.

Start small, then strengthen.

If you want a fast way to go from requirements to a working, editable application without jumping straight into a traditional pipeline, a chat-based platform like Koder.ai can be useful—especially when you value speed but still want practical controls like source code export, deployment/hosting, custom domains, and rollback.

For help estimating scope and tradeoffs, see /pricing. For deeper guides on MVP planning and safer launches, browse /blog.

Usually it means AI tools accelerate parts of the process—drafting requirements, generating UI/code snippets, suggesting data models, writing tests, or helping debug. You still need humans to define the product, verify correctness, handle security/privacy, and ship/maintain it.

A demo proves a concept on a happy path; a production app must handle real users, edge cases, security, monitoring, backups, upgrades, and support. Many “AI built it” stories are really “AI helped me make a convincing prototype.”

It’s typically strong at first drafts and repetitive work:

Common gaps include missing error handling, weak input validation, inconsistent structure, and “happy-path only” logic. Treat AI output like code from an unknown source: review it, test it, and integrate it deliberately.

Because the hard parts aren’t just typing code. You still need architecture decisions, reliable integrations, edge-case handling, QA, security/privacy work, deployment, and ongoing maintenance. AI can draft pieces, but it won’t reliably design and validate an end-to-end system for your real constraints.

Write inputs like requirements, not slogans:

An AI app builder generates an app-like scaffold from a prompt (fast, but constrained). No-code is drag-and-drop workflows you assemble (more control, still platform limits). Custom development (with AI assistance) gives maximum flexibility and ownership, but costs more upfront and needs engineering discipline.

Lock-in shows up as limits on customization, data models, hosting, and exporting the app itself. Ask early:

If owning code is non-negotiable, custom is usually safer.

Risks include insecure queries, missing authorization checks, unsafe file uploads, and accidentally committing secrets (API keys, tokens). Also, prompts may expose sensitive data to third parties. Use synthetic/redacted data, enable tool privacy controls, run secret scanning in CI, and require human review before shipping.

Start with a small, measurable MVP:

Clear constraints reduce guesswork and rework.