Jun 17, 2025·8 min

What AI Replaces in Developer Work (and What It Doesn’t)

A practical breakdown of developer responsibilities AI can replace, where it mainly augments humans, and which tasks still need full ownership in real teams.

A practical breakdown of developer responsibilities AI can replace, where it mainly augments humans, and which tasks still need full ownership in real teams.

Conversations about what “AI will do to developers” get confusing fast because we often mix up tools with responsibilities. A tool can generate code, summarize a ticket, or suggest tests. A responsibility is what the team is still accountable for when the suggestion is wrong.

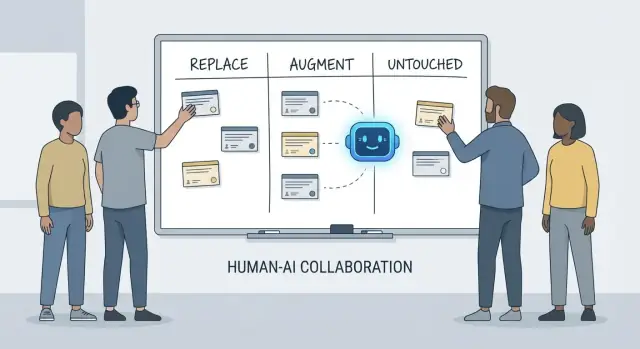

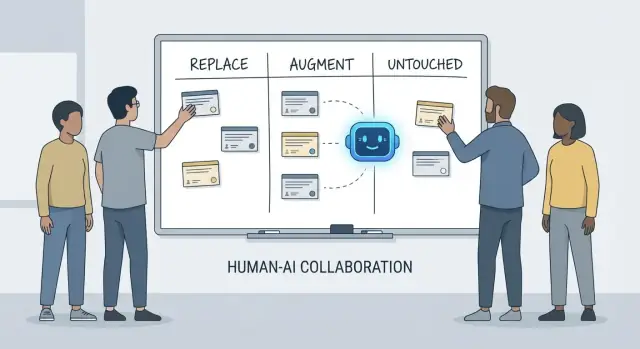

This article uses a simple framework—replace, augment, untouched—to describe day-to-day work on real teams with deadlines, legacy code, production incidents, and stakeholders who expect reliable outcomes.

Replace means the AI can complete the task end-to-end most of the time with clear guardrails, and the human role shifts to supervision and spot checks.

Examples tend to be bounded work: generating boilerplate, translating code between languages, drafting repetitive test cases, or producing first-pass documentation.

Replace does not mean “no human accountability.” If the output breaks production, leaks data, or violates standards, it’s still on the team.

Augment means the AI makes a developer faster or more thorough, but it doesn’t reliably finish the job without human judgment.

This is the common case in professional engineering: you’ll get useful drafts, alternative approaches, quick explanations, or a shortlist of likely bugs—but a developer still decides what’s correct, safe, and appropriate for the product.

Untouched means the core responsibility remains human-led because it requires context, trade-offs, and accountability that don’t compress well into prompts.

Think: negotiating requirements, choosing system-level constraints, handling incidents, setting quality bars, and making calls where there isn’t a single “right” answer.

Tools change quickly. Responsibilities change slowly.

So instead of asking “Can an AI write this code?”, ask “Who owns the outcome?” That framing keeps expectations grounded in accuracy, reliability, and accountability—things that matter more than impressive demos.

When people ask what AI “replaces” in development, they often mean tasks: write a function, generate tests, draft documentation. Teams, however, don’t ship tasks—they ship outcomes. That’s where developer responsibilities matter.

A developer’s job typically spans more than coding time:

These responsibilities sit across the whole lifecycle—from “what should we build?” to “is it safe?” to “what happens at 3 a.m. when it breaks?”

Each responsibility is really many small decisions: what edge cases matter, which metrics indicate health, when to cut scope, whether a fix is safe to ship, how to explain a trade-off to stakeholders. AI can help execute pieces of this work (draft code, propose tests, summarize logs), but responsibility is about owning the result.

Breakdowns often happen at handoff boundaries:

When ownership is unclear, work falls into the gaps.

A useful way to talk about responsibilities is decision rights:

AI can speed up execution. The decision rights—and accountability for outcomes—still need a human name next to them.

AI coding assistants are genuinely useful when the work is predictable, low-stakes, and easy to verify. Think of them as a fast junior teammate: great at producing a first pass, but still needing clear instructions and a careful check.

In practice, some teams increasingly use “vibe-coding” platforms (like Koder.ai) to speed up these replaceable chunks: generating scaffolds, wiring up CRUD flows, and producing initial drafts of UI and backend code from chat. The key is the same: guardrails, review, and clear ownership.

A lot of developer time goes into scaffolding projects and wiring things together. AI can often generate:

The guardrail here is consistency: make sure it matches your existing conventions and doesn’t invent new patterns or dependencies.

When a change is mostly mechanical—renaming a symbol across a codebase, reformatting, or updating a straightforward API usage—AI can accelerate the busywork.

Still, treat it like a bulk edit: run the full test suite, scan diffs for unintended behavior changes, and avoid letting it “improve” things beyond the requested refactor.

AI can draft READMEs, inline comments, and changelog entries based on code and commit notes. This can speed up clarity, but it can also create confident-sounding inaccuracies.

Best practice: use AI for structure and phrasing, then verify every claim—especially setup steps, configuration defaults, and edge cases.

For well-specified, pure functions, AI-generated unit tests can provide initial coverage and remind you of edge cases. The guardrail is ownership: you still choose what matters, add assertions that reflect real requirements, and ensure tests fail for the right reasons.

When you have long Slack threads, tickets, or incident logs, AI can convert them into concise notes and action items. Keep it grounded by supplying the full context and then verifying key facts, timestamps, and decisions before sharing.

AI coding assistants are at their best when you already know what you want and need help moving faster. They can reduce the time spent on “typing work” and surface helpful context, but they don’t remove the need for ownership, verification, and judgment.

Given a clear spec—inputs, outputs, edge cases, and constraints—AI can draft a reasonable starting implementation: boilerplate, data mapping, API handlers, migrations, or a straightforward refactor. The win is momentum: you get something runnable quickly.

The catch is that first-pass code often misses subtle requirements (error semantics, performance constraints, backward compatibility). Treat it like an intern’s draft: useful, but not authoritative.

When you’re choosing between approaches (e.g., caching vs. batching, optimistic vs. pessimistic locking), AI can propose alternatives and list trade-offs. This is valuable for brainstorming, but the trade-offs must be checked against your system’s realities: traffic shape, data consistency needs, operational constraints, and team conventions.

AI is also strong at explaining unfamiliar code, pointing out patterns, and translating “what is this doing?” into plain language. Paired with search tools, it can help answer “Where is X used?” and generate an impact list of likely call sites, configs, and tests to revisit.

Expect practical quality-of-life improvements: clearer error messages, small examples, and ready-to-paste snippets. These reduce friction, but they don’t replace careful review, local runs, and targeted tests—especially for changes that affect users or production systems.

AI can help you write and refine requirements, but it can’t reliably decide what you should build or why it matters. Product understanding is rooted in context: business goals, user pain, organizational constraints, edge cases, and the cost of getting it wrong. Those inputs live in conversations, history, and accountability—things a model can summarize, but not truly own.

Early requests often sound like “Make onboarding smoother” or “Reduce support tickets.” A developer’s job is to translate that into clear requirements and acceptance criteria.

That translation is mostly human work because it depends on probing questions and judgment:

AI can suggest possible metrics or draft acceptance criteria, but it won’t know which constraints are real unless someone provides them—and it won’t push back when a request is self-contradictory.

Requirements work is where uncomfortable trade-offs surface: time vs. quality, speed vs. maintainability, new features vs. stability. Teams need a person to make risks explicit, propose options, and align stakeholders on the consequences.

A good spec is not just text; it’s a decision record. It should be testable and implementable, with crisp definitions (inputs, outputs, edge cases, and failure modes). AI can help structure the document, but the responsibility for correctness—and for saying “this is ambiguous, we need a decision”—stays with humans.

System design is where “what should we build?” turns into “what should we build it on, and how will it behave when things go wrong?” AI can help you explore options, but it can’t own the consequences.

Choosing between a monolith, modular monolith, microservices, serverless, or managed platforms isn’t a quiz with one right answer. It’s a fit problem: expected scale, budget limits, time-to-market, and the team’s skills.

An assistant can summarize patterns and suggest reference architectures, but it won’t know that your team rotates on-call weekly, that hiring is slow, or that your database vendor contract renews next quarter. Those details often decide whether an architecture succeeds.

Good architecture is mostly trade-offs: simplicity vs. flexibility, performance vs. cost, speed today vs. maintainability later. AI can produce pros/cons lists quickly, which is useful—especially for documenting decisions.

What it can’t do is set priorities when trade-offs hurt. For example, “We accept slightly slower responses to keep the system simpler and easier to operate” is a business choice, not a purely technical one.

Defining service boundaries, who owns which data, and what happens during partial outages requires deep product and operational context. AI can help brainstorm failure modes (“What if the payment provider is down?”), but you still need humans to decide the expected behavior, customer messaging, and rollback plan.

Designing APIs is designing a contract. AI can help generate examples and spot inconsistencies, but you must decide versioning, backwards compatibility, and what you’re willing to support long-term.

Perhaps the most architectural decision is saying “no”—or deleting a feature. AI can’t measure opportunity cost or political risk. Teams can, and should.

Debugging is where AI often looks impressive—and where it can quietly waste the most time. An assistant can scan logs, point out suspicious code paths, or suggest a fix that “seems right.” But root-cause analysis isn’t just generating explanations; it’s proving one.

Treat AI output as hypotheses, not conclusions. Many bugs have multiple plausible causes, and AI is especially prone to picking a tidy story that matches the code snippet you pasted, not the reality of the running system.

A practical workflow is:

Reliable reproduction is a debugging superpower because it turns a mystery into a test. AI can help you write a minimal repro, draft a diagnostic script, or propose extra logging, but you decide what signals matter: request IDs, timing, environment differences, feature flags, data shape, or concurrency.

When users report symptoms (“the app froze”), you still need to translate that into system behavior: which endpoint stalled, what timeouts fired, what error-budget signals changed. That requires context: how the product is used and what “normal” looks like.

If a suggestion can’t be validated, assume it’s wrong until proven otherwise. Prefer explanations that make a testable prediction (e.g., “this will only happen on large payloads” or “only after cache warm-up”).

Even after finding the cause, the hard decision remains. AI can outline trade-offs, but humans choose the response:

Root-cause analysis is ultimately accountability: owning the explanation, the fix, and the confidence that it won’t return.

Code review isn’t just a checklist for style issues. It’s the moment a team decides what it’s willing to maintain, support, and be accountable for. AI can help you see more, but it can’t decide what matters, what fits your product intent, or what trade-offs your team accepts.

AI coding assistants can act like a tireless second set of eyes. They can quickly:

Used this way, AI shortens the time between “opened the PR” and “noticed the risk.”

Reviewing for correctness isn’t only about whether code compiles. Humans connect changes to real user behavior, production constraints, and long-term maintenance.

A reviewer still needs to decide:

Treat AI as a second reviewer, not the final approver. Ask it for a targeted pass (security checks, edge cases, backwards compatibility), then make a human decision about scope, priority, and whether the change aligns with team standards and product intent.

AI coding assistants can generate tests quickly, but they don’t own quality. A test suite is a set of bets about what can break, what must never break, and what you’re willing to ship without proving every edge case. Those bets are product and engineering decisions—still made by people.

Assistants are good at producing unit test scaffolding, mocking dependencies, and covering “happy path” behaviors from an implementation. What they can’t reliably do is decide what coverage matters.

Humans define:

Most teams need a layered strategy, not “more tests.” AI can help write many of these, but the selection and boundaries are human-led:

AI-generated tests often mirror the code too closely, creating brittle assertions or over-mocked setups that pass even when real behavior fails. Developers prevent this by:

A good strategy matches how you ship. Faster releases need stronger automated checks and clearer rollback paths; slower releases can afford heavier pre-merge validation. The quality owner is the team, not the tool.

Quality isn’t a coverage percentage. Track whether testing is improving outcomes: fewer production incidents, faster recovery, and safer changes (smaller rollbacks, quicker confident deploys). AI can speed the work, but accountability stays with developers.

Security work is less about generating code and more about making trade-offs under real constraints. AI can help surface checklists and common mistakes, but the responsibility for risk decisions stays with the team.

Threat modeling isn’t a generic exercise—what matters depends on your business priorities, users, and failure modes. An assistant can suggest typical threats (injection, broken auth, insecure defaults), yet it won’t reliably know what is truly costly for your product: account takeover vs. data leaks vs. service disruption, or which assets are legally sensitive.

AI is good at recognizing known anti-patterns, but many incidents come from app-specific details: a permissions edge case, a “temporary” admin endpoint, or a workflow that accidentally bypasses approvals. Those risks require reading the system’s intent, not just the code.

Tools can remind you not to hardcode keys, but they can’t own the full policy:

AI may flag outdated libraries, but teams still need practices: pinning versions, verifying provenance, reviewing transitive dependencies, and deciding when to accept risk vs. invest in remediation.

Compliance isn’t “add encryption.” It’s controls, documentation, and accountability: access logs, approval trails, incident procedures, and proof you followed them. AI can draft templates, but humans must validate evidence and sign off—because that’s what auditors (and customers) ultimately rely on.

AI can make ops work faster, but it doesn’t take ownership. Reliability is a chain of decisions under uncertainty, and the cost of a wrong call is usually higher than the cost of a slow one.

AI is useful for drafting and maintaining operational artifacts—runbooks, checklists, and “if X then try Y” playbooks. It can also summarize logs, cluster similar alerts, and propose first-pass hypotheses.

For reliability work, that translates into quicker iteration on:

These are great accelerators, but they’re not the work itself.

Incidents rarely follow the script. On-call engineers deal with unclear signals, partial failures, and messy trade-offs while the clock is ticking. AI can suggest likely causes, but it can’t reliably decide whether to page another team, disable a feature, or accept short-term customer impact to preserve data integrity.

Deployment safety is another human responsibility. Tools can recommend rollbacks, feature flags, or staged releases, but teams still need to choose the safest path given business context and blast radius.

AI can draft timelines and pull key events from chat, tickets, and monitoring. Humans still do the critical parts: deciding what “good” looks like, prioritizing fixes, and making changes that prevent repeats (not just the same symptom).

If you treat AI as a co-pilot for ops paperwork and pattern-finding—not an incident commander—you’ll get speed without surrendering accountability.

AI can explain concepts clearly and on demand: “What’s CQRS?”, “Why does this deadlock happen?”, “Summarize this PR.” That helps teams move faster. But communication at work isn’t only about transferring information—it’s about building trust, establishing shared habits, and making commitments people can rely on.

New developers don’t just need answers; they need context and relationships. AI can help by summarizing modules, suggesting reading paths, and translating jargon. Humans still have to teach what matters here: which trade-offs the team prefers, what “good” looks like in this codebase, and who to talk to when something feels off.

Most project friction shows up between roles: product, design, QA, security, support. AI can draft meeting notes, propose acceptance criteria, or rephrase feedback more neutrally. People still need to negotiate priorities, resolve ambiguity, and notice when a stakeholder is “agreeing” without actually agreeing.

Teams fail when responsibility is fuzzy. AI can generate checklists, but it can’t enforce accountability. Humans must define what “done” means (tests? docs? rollout plan? monitoring?), and who owns what after merge—especially when AI-generated code hides complexity.

It separates tasks (things a tool can help execute) from responsibilities (outcomes your team is accountable for).

Because teams don’t ship “tasks,” they ship outcomes.

Even if an assistant drafts code or tests, your team still owns:

“Replace” means bounded, verifiable, low-stakes work where mistakes are easy to catch.

Good candidates include:

Use guardrails that make errors obvious and cheap:

Because “augment” work usually contains hidden constraints the model won’t reliably infer:

Treat AI output as a draft you adapt to your system, not an authoritative solution.

Use it to generate hypotheses and an evidence plan, not conclusions.

A practical loop:

If you can’t validate a suggestion, assume it’s wrong until proven otherwise.

AI can help you notice issues faster, but humans decide what’s acceptable to ship.

Useful AI review prompts:

Then do a human pass for intent, maintainability, and release risk (what is release-blocking vs. follow-up).

AI can draft lots of tests, but it can’t choose what coverage actually matters.

Keep humans responsible for:

Use AI for scaffolding and edge-case brainstorming, not as the quality owner.

Not reliably, because these decisions depend on business context and long-term accountability.

AI can:

Humans must still decide:

Never paste secrets or sensitive customer/incident data into prompts.

Practical rules: