Sep 08, 2025·8 min

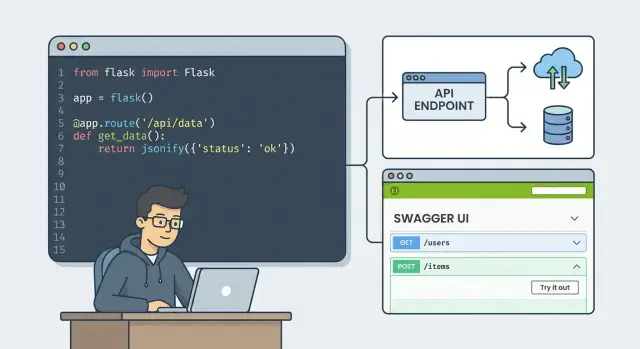

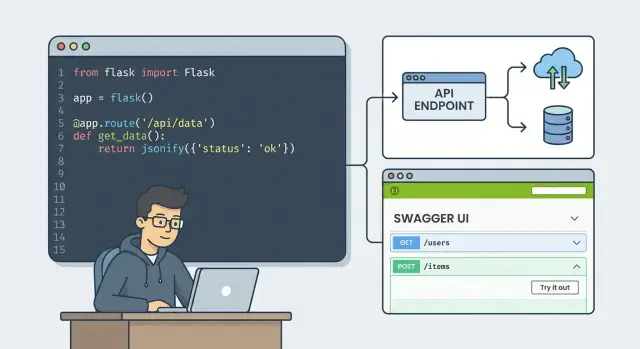

What Is FastAPI? A Practical Guide for Building APIs

FastAPI is a modern Python framework for building APIs quickly, with type hints, validation, and automatic OpenAPI docs. Learn the basics and uses.

FastAPI is a modern Python framework for building APIs quickly, with type hints, validation, and automatic OpenAPI docs. Learn the basics and uses.

FastAPI is a Python framework for building web APIs quickly, with clear code and automatic documentation. You write small functions (called “endpoints”) that declare what data your API accepts and what it returns, and FastAPI handles the web plumbing—routing, validation, and producing JSON responses.

An API is a set of URLs that lets one piece of software talk to another.

For example, a weather app on your phone might call a URL like GET /weather?city=Berlin. The server replies with structured data (usually JSON), such as temperature and forecast. The phone app doesn’t need direct access to the server’s database—it just asks the API and displays the result.

FastAPI helps you create those URLs and responses in Python.

You don’t need to be an async expert to start; you can write simple endpoints and adopt more advanced patterns as you grow.

FastAPI caught on quickly because it removes a lot of the everyday friction people hit when building APIs in Python.

Traditional API projects often start with slow setup and lots of “plumbing”:

FastAPI’s core features target these problems directly, so teams spend more time designing endpoints and less time fighting framework boilerplate.

FastAPI leans heavily on Python type hints. When you declare that a field is an int, optional, or a list of something, FastAPI uses that information to validate inputs and shape outputs.

This reduces “stringly-typed” mistakes (for example, treating an ID as text in one place and a number in another) and encourages consistent endpoint behavior. It’s still Python, but with clearer expectations baked into the function signatures.

Because the API schema is derived from the code, FastAPI can generate interactive documentation automatically (OpenAPI + Swagger UI/ReDoc). That matters for collaboration: frontend developers, QA, and integrators can explore endpoints, try requests, and see exact models without waiting for a separate docs effort.

FastAPI won’t fix a poorly designed API. You still need good naming, versioning, error handling, and security decisions. What it does offer is a cleaner path from “idea” to “well-defined API” with fewer surprises along the way.

FastAPI feels straightforward once you understand a few core ideas it builds on. You don’t need to memorize internals—just recognize the moving parts you’ll use every day.

A framework is a set of tools and conventions for building an API without starting from scratch. FastAPI provides the “plumbing” for common API tasks: defining endpoints, reading input, returning output, handling errors, and organizing code into a maintainable structure.

Routing is how you map a URL and HTTP method to a piece of Python code.

For example, you might route GET /users to “list users” and POST /users to “create a user.” In FastAPI, you typically define routes with decorators like @app.get(...) and @app.post(...), which makes it easy to see what your API offers at a glance.

Every API call is a request (what the client sends) and a response (what your server returns).

FastAPI helps you:

/users/{id}), query string (?page=2), headers, and request body200, 201, 404)FastAPI runs on ASGI, a modern standard for Python web servers. Practically, this means FastAPI is designed to handle many connections efficiently, and it can support features like long-lived connections (for example, WebSockets) when you need them—without you having to manage low-level networking.

Python type hints (like str, int, list[Item]) aren’t just documentation in FastAPI—they’re a key input. FastAPI uses them to understand what data you expect, convert incoming values to the right types, and produce clearer, more predictable APIs.

Pydantic models let you define the shape of data (fields, types, optional values) in one place. FastAPI uses these models to validate incoming JSON, reject invalid input with helpful error messages, and serialize output consistently—so your API behaves reliably even when clients send messy data.

FastAPI apps are built around endpoints: a URL path plus an HTTP method. Think of an endpoint as “what the client asks for” and “how they ask for it.” For example, a client might GET /users to list users, or POST /users to create one.

A path is the route, and the method is the action:

GET /products → fetch dataPOST /products → send data to create somethingPUT /products/123 → replace/update somethingDELETE /products/123 → remove somethingFastAPI separates data that’s part of the path from data that’s optional “filters” on the request.

GET /users/42 → 42 is the user ID.? and typically optional.

GET /users?limit=10&active=true → limit and active control how results are returned.When a client sends structured data (usually JSON), it goes in the request body, most often with POST or PUT.

Example: POST /orders with JSON like { "item_id": 3, "quantity": 2 }.

FastAPI can return plain Python objects (like dicts), but it shines when you define a response model. That model acts as a contract: fields are shaped consistently, extra data can be filtered out, and types are enforced. The result is cleaner APIs—clients know what to expect, and you avoid “surprise” responses that break integrations.

“Async” (short for asynchronous) is a way for your API to handle many requests efficiently when a lot of time is spent waiting.

Imagine a barista taking orders. If they had to stand still and do nothing while the espresso machine runs, they’d serve fewer customers. A better approach is: start the coffee, then take the next order while the machine works.

Async works like that. Your FastAPI app can start an operation that waits on something slow—like a network request or a database query—and while it’s waiting, it can move on to handle other incoming requests.

Async shines when your API does a lot of I/O (input/output) work—things that spend time waiting rather than “thinking.” Common examples:

If your endpoints frequently wait on these operations, async can improve throughput and reduce the chance that requests pile up under load.

Async is not a magic speed button for everything. If your endpoint is mostly CPU-heavy—like resizing large images, running data science calculations, or encrypting big payloads—async won’t make the computation itself faster. In those cases, you typically need different tactics (background workers, process pools, or scaling out).

You don’t have to rewrite everything to use FastAPI. You can write regular (sync) route functions and FastAPI will run them fine. Many projects mix both styles: keep simple endpoints synchronous, and use async def where it clearly helps (usually around database calls or external HTTP requests).

Validation is the checkpoint between the outside world and your code. When an API accepts input (JSON body, query params, path params), you want to be sure it’s complete, correctly typed, and within reasonable limits—before you write to a database, call another service, or trigger business logic.

FastAPI relies on Pydantic models for this. You describe what “good data” looks like once, and FastAPI automatically:

If a client sends the wrong shape of data, FastAPI responds with a 422 Unprocessable Entity and a structured error payload that points to the exact field and reason. That makes it easier for client developers to fix requests quickly, without guessing.

Here’s a small model showing required fields, types, min/max constraints, and formats:

from pydantic import BaseModel, EmailStr, Field

class UserCreate(BaseModel):

email: EmailStr

age: int = Field(ge=13, le=120)

username: str = Field(min_length=3, max_length=20)

email must be present.age must be an integer.age is limited to 13–120.EmailStr enforces a valid email shape.The same models can shape output, so your API responses don’t accidentally leak internal fields. You return Python objects; FastAPI (via Pydantic) turns them into JSON with the right field names and types.

One of FastAPI’s most practical features is that it generates API documentation for you automatically—based on the code you already wrote.

OpenAPI is a standard way to describe an API in a structured format (usually JSON). Think of it as a “contract” that spells out:

GET /users/{id})Because it’s machine-readable, tools can use it to generate test clients, validate requests, and keep teams aligned.

FastAPI serves two human-friendly docs pages automatically:

In a typical FastAPI project, you’ll find them at:

/docs (Swagger UI)/redoc (ReDoc)When you change your path parameters, request models, response models, or validation rules, the OpenAPI schema (and the docs pages) update automatically. No separate “docs maintenance” step.

A FastAPI app can be tiny and still feel “real.” You define a Python object called app, add a couple of routes, and run a local server to try it in your browser.

Here’s the smallest useful example:

from fastapi import FastAPI

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def read_root():

return {"message": "Hello, FastAPI"}

That’s it: one route (GET /) that returns JSON.

To make it feel like an API, let’s store items in a list. This is not a database—data resets when the server restarts—but it’s perfect for learning.

from fastapi import FastAPI

app = FastAPI()

items = []

@app.post("/items")

def create_item(name: str):

item = {"id": len(items) + 1, "name": name}

items.append(item)

return item

@app.get("/items")

def list_items():

return items

You can now:

POST /items?name=Coffee to add an itemGET /items to retrieve the listA common starter structure is:

main.py (creates app and routes)requirements.txt or pyproject.toml (dependencies)You typically:

uvicorn main:app --reload)http://127.0.0.1:8000 and try the endpointsFastAPI “dependencies” are shared inputs your endpoints need to do their job—things like a database session, the current logged-in user, app settings, or common query parameters. Instead of manually creating or parsing these in every route, you define them once and let FastAPI provide them wherever they’re needed.

A dependency is usually a function (or class) that returns a value your endpoint can use. FastAPI will call it for you, figure out what it needs (based on its parameters), and inject the result into your path operation function.

This is often called dependency injection, but you can think of it as: “declare what you need, and FastAPI wires it up.”

Without dependencies, you might:

With dependencies, you centralize that logic. If you later change how you create a DB session or how you load the current user, you update one place—not dozens of endpoints.

page/limit parsing and validation.Here’s the conceptual pattern you’ll see in many FastAPI apps:

from fastapi import Depends, FastAPI

app = FastAPI()

def get_settings():

return {"items_per_page": 20}

@app.get("/items")

def list_items(settings=Depends(get_settings)):

return {"limit": settings["items_per_page"]}

You declare the dependency with Depends(...), and FastAPI passes its result into your endpoint parameter. The same approach works for more complex building blocks (like get_db() or get_current_user()), helping your code stay cleaner as your API grows.

FastAPI doesn’t “auto-secure” your API—you choose the scheme and wire it into your endpoints. The good news is that FastAPI provides building blocks (especially through its dependency system) that make common security patterns straightforward to implement.

Authentication answers: “Who are you?” Authorization answers: “What are you allowed to do?”

Example: a user may be authenticated (valid login/token) but still not authorized to access an admin-only route.

X-API-Key). Manage rotation and revocation.FastAPI supports these patterns via utilities like fastapi.security and by documenting them cleanly in OpenAPI.

If you store user passwords, never store plain text. Store a salted, slow hash (e.g., bcrypt/argon2 via a well-known library). Also consider rate limiting and account lockout policies.

Security is about details: token storage, CORS settings, HTTPS, secret management, and correct authorization checks on every sensitive endpoint. Treat built-in helpers as a starting point, and validate your approach with reviews and tests before relying on it in production.

Testing is where FastAPI’s “it works on my machine” promise turns into confidence you can ship. The good news: FastAPI is built on Starlette, so you get strong testing tools without a lot of setup.

Unit tests focus on small pieces: a function that calculates a value, a dependency that loads the current user, or a service method that talks to the database (often mocked).

Integration tests exercise the API end-to-end: you call an endpoint and assert on the full HTTP response. These are the tests that catch routing mistakes, dependency wiring issues, and validation problems.

A healthy test suite usually has more unit tests (fast) and fewer integration tests (higher confidence).

FastAPI apps can be tested “like a client” using Starlette’s TestClient, which sends requests to your app in-process—no server needed.

from fastapi.testclient import TestClient

from app.main import app

client = TestClient(app)

def test_healthcheck():

r = client.get("/health")

assert r.status_code == 200

Test the things users and other systems rely on:

Use predictable data, isolate external services (mock or use a test DB), and avoid shared state between tests. Fast tests get run; slow tests get skipped.

Getting a FastAPI app online is mostly about choosing the right “runner” and adding a few production essentials.

When you run uvicorn main:app --reload locally, you’re using a development setup: auto-reload, chatty errors, and settings that prioritize convenience.

In production, you typically run Uvicorn without reload, often behind a process manager (like Gunicorn with Uvicorn workers) or behind a reverse proxy. The goal is stability: controlled restarts, predictable performance, and safer defaults.

A common pattern is:

This keeps one codebase deployable to multiple environments without editing files.

Before you call it “done,” confirm you have:

/health for uptime monitoring and load balancers.If you’re moving from “working locally” to “shippable,” it also helps to standardize how you generate and manage your API contract. Some teams pair FastAPI’s OpenAPI output with automated workflows—for example, generating clients, validating requests in CI, and deploying consistently. Tools like Koder.ai can also fit into this stage: you can describe the API you want in chat, iterate on endpoints and models quickly, and then export source code for a normal review/deploy pipeline.

FastAPI is a strong choice when you want a clean, modern way to build REST APIs in Python—especially if you care about clear request/response models and predictable behavior as your API grows.

FastAPI tends to shine in these situations:

FastAPI isn’t always the simplest answer:

FastAPI can be very fast in practice, but speed depends on your database calls, network latency, and business logic. Expect solid throughput and good latency for typical API workloads—just avoid assuming the framework alone will “fix” slow I/O or inefficient queries.

If FastAPI sounds like a match, focus next on routing patterns, Pydantic models, database integration, background tasks, and basic authentication.

A practical path is to build a small endpoint set, then expand with reusable dependencies and tests as your API grows. If you want to accelerate the early scaffolding (routes, models, and the first deployment-ready structure), consider using a vibe-coding workflow—e.g., mapping your endpoints in a “planning mode” and iterating from a single spec. That’s one area where Koder.ai can be useful: you can prototype an API-driven app from chat, then refine the generated code and export it when you’re ready to run it like any standard project.

FastAPI is a Python web framework for building APIs with minimal boilerplate. You write endpoint functions (like @app.get("/users")) and FastAPI handles routing, request parsing, validation, and JSON responses.

A key benefit is that your type hints and Pydantic models act as an explicit contract for what the API accepts and returns.

An API is a set of URLs (endpoints) that other software can call to exchange data.

For example, a client might request weather data with GET /weather?city=Berlin, and the server responds with structured JSON. The client doesn’t need direct database access—it just uses the API response.

Routing maps an HTTP method + path to a Python function.

In FastAPI you typically use decorators:

@app.get("/items") for read operations@app.post("/items") for create operations@app.put("/items/{id}") to update/replacePath parameters are part of the URL structure and usually identify a specific resource (required).

GET /users/42 → 42 is a path parameterQuery parameters are appended after ? and are usually optional filters or controls.

Pydantic models define the shape and rules of your data (types, required fields, constraints). FastAPI uses them to:

If validation fails, FastAPI typically responds with 422 Unprocessable Entity and details about which field is wrong.

FastAPI automatically generates an OpenAPI schema from your endpoints, type hints, and models.

You usually get interactive docs for free:

/docs/redocBecause the schema is derived from code, the docs stay in sync as you change parameters and models.

Use async def when your endpoint spends time waiting on I/O (database calls, external HTTP requests, file/object storage).

Use regular def when:

Mixing sync and async endpoints in the same app is common.

Dependencies are reusable “building blocks” that FastAPI injects into endpoints via Depends().

They’re commonly used for:

This reduces repetition and centralizes cross-cutting logic so changes happen in one place.

FastAPI doesn’t secure your API by default—you choose an approach and apply it consistently.

Common patterns include:

Also remember the basics:

For testing, you can use FastAPI/Starlette’s TestClient to call your API in-process (no server required).

Practical items to assert:

For deployment, run an ASGI server (often Uvicorn; sometimes behind Gunicorn or a reverse proxy) and add production essentials like logging, health checks (e.g., ), timeouts, and environment-based configuration.

@app.delete("/items/{id}")This makes your API surface easy to scan directly from code.

GET /users?limit=10&active=true → limit, active are query parameters/health