Oct 14, 2025·8 min

What Is GraphQL? A Clear Guide for APIs and Data Fetching

Learn what GraphQL is, how queries, mutations, and schemas work, and when to use it instead of REST—plus practical pros, cons, and examples.

Learn what GraphQL is, how queries, mutations, and schemas work, and when to use it instead of REST—plus practical pros, cons, and examples.

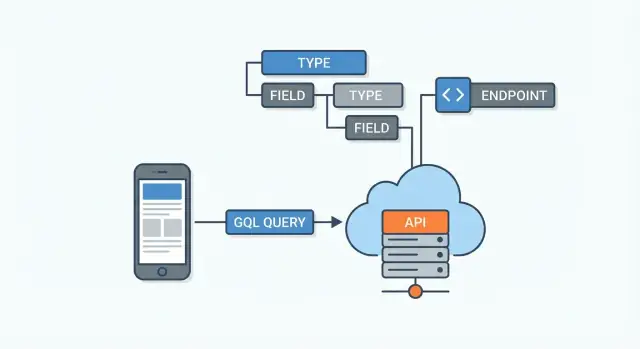

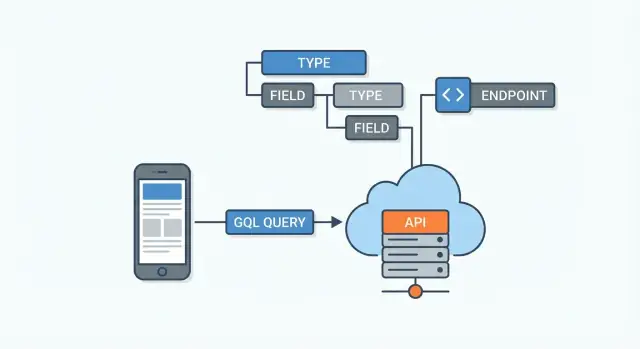

GraphQL is a query language and a runtime for APIs. Put simply: it’s a way for an app (web, mobile, or another service) to ask an API for data using a clear, structured request—and for the server to return a response that matches that request.

Many APIs force clients to accept whatever a fixed endpoint returns. That often leads to two issues:

With GraphQL, the client can request exactly the fields it needs, no more and no less. This is especially useful when different screens (or different apps) need different “slices” of the same underlying data.

GraphQL typically sits between client apps and your data sources. Those data sources might be:

The GraphQL server receives a query, figures out how to fetch each requested field from the right place, and then assembles the final JSON response.

Think of GraphQL as ordering a custom-shaped response:

GraphQL is often misunderstood, so here are a few clarifications:

If you keep that core definition—query language + runtime for APIs—you’ll have the right foundation for everything else.

GraphQL was created to solve a practical product problem: teams were spending too much time making APIs fit real UI screens.

Traditional endpoint-based APIs often force a choice between shipping data you don’t need or making extra calls to get what you do need. As products grow, that friction shows up as slower pages, more complicated client code, and painful coordination between frontend and backend teams.

Over-fetching happens when an endpoint returns a “full” object even if a screen only needs a few fields. A mobile profile view might only need a name and avatar, but the API returns addresses, preferences, audit fields, and more. That wastes bandwidth and can hurt user experience.

Under-fetching is the opposite: no single endpoint has everything a view needs, so the client must make multiple requests and stitch results together. That adds latency and increases the chances of partial failures.

Many REST-style APIs respond to change by adding new endpoints or versioning (v1, v2, v3). Versioning can be necessary, but it creates long-lived maintenance work: old clients keep using old versions, while new features pile up elsewhere.

GraphQL’s approach is to evolve the schema by adding fields and types over time, while keeping existing fields stable. That often reduces the pressure to create “new versions” just to support new UI needs.

Modern products rarely have just one consumer. Web, iOS, Android, and partner integrations all need different data shapes.

GraphQL was designed so each client can request exactly the fields it needs—without the backend creating a separate endpoint for every screen or device.

A GraphQL API is defined by its schema. Think of it as the agreement between the server and every client: it lists what data exists, how it’s connected, and what can be requested or changed. Clients don’t guess endpoints—they read the schema and ask for specific fields.

The schema is made of types (like User or Post) and fields (like name or title). Fields can point to other types, which is how GraphQL models relationships.

Here’s a simple example in Schema Definition Language (SDL):

type User {

id: ID!

name: String!

posts: [Post!]!

}

type Post {

id: ID!

title: String!

body: String

author: User!

comments: [Comment!]!

}

type Comment {

id: ID!

text: String!

author: User!

post: Post!

}

Because the schema is strongly typed, GraphQL can validate a request before running it. If a client asks for a field that doesn’t exist (for example, Post.publishDate when the schema has no such field), the server can reject or partially fulfill the request with clear errors—without ambiguous “maybe it works” behavior.

Schemas are designed to grow. You can usually add new fields (like User.bio) without breaking existing clients, because clients only receive what they ask for. Removing or changing fields is more sensitive, so teams often deprecate fields first and migrate clients gradually.

A GraphQL API is typically exposed through a single endpoint (for example, /graphql). Instead of having many URLs for different resources (like /users, /users/123, /users/123/posts), you send a query to one place and describe the exact data you want back.

A query is basically a “shopping list” of fields. You can request simple fields (like id and name) and also nested data (like a user’s recent posts) in the same request—without downloading extra fields you don’t need.

Here’s a small example:

query GetUserWithPosts {

user(id: "123") {

id

name

posts(limit: 2) {

id

title

}

}

}

GraphQL responses are predictable: the JSON you get back mirrors the structure of your query. That makes it easier to work with on the frontend, because you don’t have to guess where data will appear or parse different response formats.

A simplified response outline might look like:

{

"data": {

"user": {

"id": "123",

"name": "Sam",

"posts": [

{ "id": "p1", "title": "Hello GraphQL" },

{ "id": "p2", "title": "Queries in Practice" }

]

}

}

}

If you don’t ask for a field, it won’t be included. If you do ask for it, you can expect it in the matching spot—making GraphQL queries a clean way to fetch exactly what each screen or feature needs.

Queries are for reading; mutations are how you change data in a GraphQL API—creating, updating, or deleting records.

Most mutations follow the same pattern:

input object) such as the fields to update.GraphQL mutations usually return data on purpose, rather than just “success: true”. Returning the updated object (or at least its id and key fields) helps the UI:

A common design is a “payload” type that includes both the updated entity and any errors.

mutation UpdateEmail($input: UpdateUserEmailInput!) {

updateUserEmail(input: $input) {

user {

id

email

}

errors {

field

message

}

}

}

For UI-driven APIs, a good rule is: return what you need to render the next state (for example, the updated user plus any errors). That keeps the client simple, avoids guessing what changed, and makes failures easier to handle gracefully.

A GraphQL schema describes what can be asked for. Resolvers describe how to actually get it. A resolver is a function attached to a specific field in your schema. When a client requests that field, GraphQL calls the resolver to fetch or compute the value.

GraphQL executes a query by walking the requested shape. For each field, it finds the matching resolver and runs it. Some resolvers simply return a property from an object already in memory; others call a database, another service, or combine multiple sources.

For example, if your schema has User.posts, the posts resolver might query a posts table by userId, or call a separate Posts service.

Resolvers are the glue between the schema and your real systems:

This mapping is flexible: you can change your backend implementation without changing the client query shape—so long as the schema stays consistent.

Because resolvers can run per field and per item in a list, it’s easy to accidentally trigger many small calls (for example, fetching posts for 100 users with 100 separate queries). This “N+1” pattern can make responses slow.

Common fixes include batching and caching (e.g., collecting IDs and fetching in one query) and being intentional about which nested fields you encourage clients to request.

Authorization is often enforced in resolvers (or shared middleware) because resolvers know who is asking (via context) and what data they’re accessing. Validation typically happens at two levels: GraphQL handles type/shape validation automatically, while resolvers enforce business rules (like “only admins can set this field”).

One thing that surprises people new to GraphQL is that a request can “succeed” and still include errors. That’s because GraphQL is field-oriented: if some fields can be resolved and others can’t, you may get partial data back.

A typical GraphQL response can contain both data and an errors array:

{

"data": {

"user": {

"id": "123",

"email": null

}

},

"errors": [

{

"message": "Not authorized to read email",

"path": ["user", "email"],

"extensions": { "code": "FORBIDDEN" }

}

]

}

This is useful: the client can still render what it has (for example, the user profile) while handling the missing field.

data is often null.Write error messages for the end user, not for debugging. Avoid exposing stack traces, database names, or internal IDs. A good pattern is:

messageextensions.coderetryable: true)Log the detailed error server-side with a request ID so you can investigate without exposing internals.

Define a small error “contract” your web and mobile apps share: common extensions.code values (like UNAUTHENTICATED, FORBIDDEN, BAD_USER_INPUT), when to show a toast vs inline field errors, and how to handle partial data. Consistency here prevents every client from inventing its own error rules.

Subscriptions are GraphQL’s way to push data to clients as it changes, instead of making the client ask repeatedly. They’re typically delivered over a persistent connection (most commonly WebSockets), so the server can send events the moment something happens.

A subscription looks a lot like a query, but the result isn’t a single response. It’s a stream of results—each one representing an event.

Under the hood, a client “subscribes” to a topic (for example, messageAdded in a chat app). When the server publishes an event, any connected subscribers receive a payload that matches the subscription’s selection set.

Subscriptions shine when people expect changes instantly:

With polling, the client asks “Anything new?” every N seconds. It’s simple, but it can waste requests (especially when nothing changes) and still feels delayed.

With subscriptions, the server says “Here’s the update” immediately. That can reduce unnecessary traffic and improve perceived speed—at the cost of keeping connections open and managing real-time infrastructure.

Subscriptions aren’t always worth it. If updates are infrequent, not time-sensitive, or easy to batch, polling (or just re-fetching after user actions) is often enough.

They can also add operational overhead: connection scaling, auth on long-lived sessions, retries, and monitoring. A good rule: use subscriptions only when real-time is a product requirement, not just a nice-to-have.

GraphQL is often described as “power to the client,” but that power has costs. Knowing the tradeoffs up front helps you decide when GraphQL is a great fit—and when it might be overkill.

The biggest win is flexible data fetching: clients can request exactly the fields they need, which can reduce over-fetching and make UI changes faster.

Another major advantage is the strong contract provided by a GraphQL schema. The schema becomes a single source of truth for types and available operations, which improves collaboration and tooling.

Teams often see better client productivity because front-end developers can iterate without waiting for new endpoint variations, and tools like Apollo Client can generate types and streamline data fetching.

GraphQL can make caching more complex. With REST, caching is often “per URL.” With GraphQL, many queries share the same endpoint, so caching relies on query shapes, normalized caches, and careful server/client configuration.

On the server side, there are performance pitfalls. A seemingly small query can trigger many backend calls unless you design resolvers carefully (batching, avoiding N+1 patterns, and controlling expensive fields).

There’s also a learning curve: schemas, resolvers, and client patterns can be unfamiliar to teams used to endpoint-based APIs.

Because clients can ask for a lot, GraphQL APIs should enforce query depth and complexity limits to prevent abusive or accidental “too big” requests.

Authentication and authorization should be enforced per field, not only at the route level, since different fields may have different access rules.

Operationally, invest in logging, tracing, and monitoring that understand GraphQL: track operation names, variables (carefully), resolver timings, and error rates so you can spot slow queries and regressions early.

GraphQL and REST both help apps talk to servers, but they structure that conversation in very different ways.

REST is resource-based. You fetch data by calling multiple endpoints (URLs) that represent “things” like /users/123 or /orders?userId=123. Each endpoint returns a fixed shape of data decided by the server.

REST also leans on HTTP semantics: methods like GET/POST/PUT/DELETE, status codes, and caching rules. That can make REST feel natural when you’re doing straightforward CRUD or working closely with browser/proxy caches.

GraphQL is schema-based. Instead of many endpoints, you usually have one endpoint, and the client sends a query describing the exact fields it wants. The server validates that request against the GraphQL schema and returns a response that matches the query shape.

This “client-driven selection” is why GraphQL can reduce over-fetching (too much data) and under-fetching (not enough data), especially for UI screens that need data from several related models.

REST is often the better fit when:

Many teams mix both:

The practical question isn’t “Which is better?” but “Which fits this use case with the least complexity?”

Designing a GraphQL API is easiest when you treat it as a product for the people building screens, not as a mirror of your database. Start small, validate with real use cases, and expand as needs grow.

List your key screens (e.g., “Product list”, “Product details”, “Checkout”). For each screen, write down the exact fields it needs and the interactions it supports.

This helps you avoid “god queries,” reduces over-fetching, and clarifies where you’ll need filtering, sorting, and pagination.

Define your core types first (e.g., User, Product, Order) and their relationships. Then add:

Prefer business-language naming over database naming. “placeOrder” communicates intent better than “createOrderRecord”.

Keep naming consistent: singular for items (product), plural for collections (products). For pagination, you’ll usually choose one:

Even at a high level, decide early because it shapes your API’s response structure.

GraphQL supports descriptions directly in the schema—use them for fields, arguments, and edge cases. Then add a few copy-paste examples in your docs (including pagination and common error scenarios). A well-described schema makes introspection and API explorers far more useful.

Starting with GraphQL is mostly about picking a few well-supported tools and setting up a workflow you can trust. You don’t need to adopt everything at once—get one query working end-to-end, then expand.

Choose a server based on your stack and how much “batteries included” you want:

A practical first step: define a small schema (a couple of types + one query), implement resolvers, and connect a real data source (even if it’s a stubbed in-memory list).

If you want to move faster from “idea” to a working API, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you scaffold a small full-stack app (React on the frontend, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend) and iterate on GraphQL schema/resolvers via chat—then export the source code when you’re ready to own the implementation.

On the frontend, your choice usually depends on whether you want opinionated conventions or flexibility:

If you’re migrating from REST, start by using GraphQL for one screen or feature, and keep REST for the rest until the approach proves itself.

Treat your schema like an API contract. Useful layers of testing include:

To deepen your understanding, continue with:

GraphQL is a query language and runtime for APIs. Clients send a query describing the exact fields they want, and the server returns a JSON response that mirrors that shape.

It’s best thought of as a layer between clients and one or more data sources (databases, REST services, third-party APIs, microservices).

GraphQL primarily helps with:

By letting the client request only specific fields (including nested fields), GraphQL can reduce extra data transfer and simplify client code.

GraphQL is not:

Treat it as an API contract + execution engine, not a storage or performance magic bullet.

Most GraphQL APIs expose a single endpoint (often /graphql). Instead of multiple URLs, you send different operations (queries/mutations) to that one endpoint.

Practical implication: caching and observability usually key off the operation name + variables, not the URL.

The schema is the API contract. It defines:

User, Post)User.name)User.posts)Because it’s , the server can validate queries before executing them and give clear errors when fields don’t exist.

GraphQL queries are read operations. You specify the fields you need, and the response JSON matches the query’s structure.

Tips:

query GetUserWithPosts) for better debugging and monitoring.posts(limit: 2)).Mutations are write operations (create/update/delete). A common pattern is:

input objectReturning data (not just success: true) helps the UI update immediately and keeps caches consistent.

Resolvers are field-level functions that tell GraphQL how to fetch or compute each field.

In practice, resolvers might:

Authorization is often enforced in resolvers (or shared middleware) because they know who is requesting what data.

It’s easy to create an N+1 pattern (e.g., loading posts separately for each of 100 users).

Common mitigations:

Measure resolver timing and watch for repeated downstream calls during one request.

GraphQL can return partial data alongside an errors array. That happens when some fields resolve successfully and others fail (e.g., forbidden field, timeout in a downstream service).

Good practices:

message stringsextensions.code values (e.g., FORBIDDEN, BAD_USER_INPUT)Clients should decide when to render partial data vs. treat the operation as a full failure.