Sep 07, 2025·8 min

What Is jQuery, and Why Do People Say It’s Forgotten?

jQuery made JavaScript easier with simple DOM, events, and AJAX. Learn what it is, why it declined, and when it still makes sense today.

jQuery made JavaScript easier with simple DOM, events, and AJAX. Learn what it is, why it declined, and when it still makes sense today.

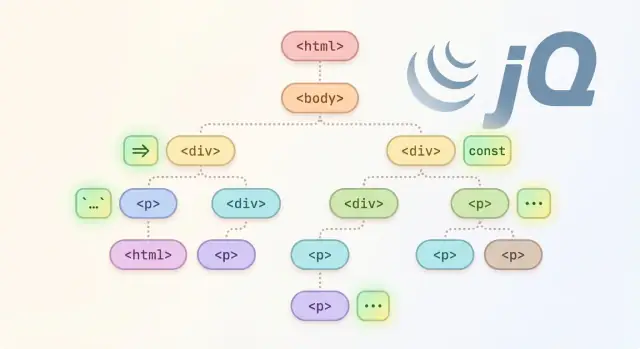

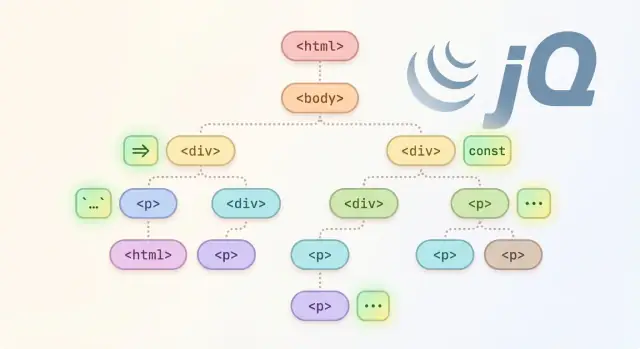

jQuery is a small JavaScript library that makes common tasks on a web page easier—things like selecting elements, reacting to clicks, changing text, showing/hiding parts of the page, and sending requests to a server.

If you’ve ever seen code like $("button").click(...), that’s jQuery. The $ is just a shortcut for “find something on the page and do something with it.”

This guide is practical and non-technical: what jQuery is, why it became popular, why newer projects don’t reach for it as often, and how to deal with it if your site still uses it. It’s intentionally longer so we can include clear examples and real-world guidance rather than quick opinions.

When people say jQuery is “forgotten,” they usually don’t mean it disappeared. They mean:

So the story isn’t “jQuery is dead.” It’s more like: jQuery moved from being the default tool for front-end work to being a legacy dependency you may inherit—and occasionally still choose on purpose.

Before jQuery, front-end work often meant writing the same small, annoying bits of code over and over—then testing them in multiple browsers and discovering they behaved differently. Even simple goals like “find this element,” “attach a click handler,” or “send a request” could turn into a pile of special cases.

A lot of early JavaScript was less about building features and more about wrestling with the environment. You’d write code that worked in one browser, then add extra branches to make it work in another. Teams kept their own internal “mini libraries” of helper functions just to survive day-to-day UI changes.

The result: slower development, more bugs, and a constant fear that a tiny change would break an older browser your users still relied on.

Browsers didn’t agree on important details. DOM selection methods, event handling, and even how to get element sizes could vary. Internet Explorer, in particular, had different APIs for events and XMLHTTP requests, so “standard” code wasn’t always truly portable.

That mattered because websites weren’t built for one browser. If your checkout form, navigation menu, or modal dialog failed in a popular browser, it was a real business problem.

jQuery became a big deal because it offered a consistent, friendly API that smoothed out those differences.

It made common tasks dramatically simpler:

Just as importantly, jQuery’s “write less, do more” style helped teams ship faster with fewer browser-specific surprises—especially in an era when “modern DOM APIs” weren’t as capable or widely supported as they are now.

jQuery’s real superpower wasn’t that it introduced brand-new ideas—it was that it made common browser tasks feel consistent and easy across different browsers. If you’re reading older front-end code, you’ll typically see jQuery used for four everyday jobs.

$ function idea)The $() function let you “grab” elements using CSS-like selectors and then work with them as a group.

Instead of juggling browser quirks and verbose APIs, you could select all items, find a child element, or move up to a parent with short, chainable calls.

jQuery made it simple to respond to user actions:

click for buttons and linkssubmit for formsready to run code when the page was loadedIt also smoothed over differences in how browsers handled event objects and binding, which mattered a lot when browser support was uneven.

Before fetch() became standard, jQuery’s $.ajax(), $.get(), and $.post() were a straightforward way to request data from a server and update the page without reloading.

This enabled patterns that now feel normal—live search, “load more” buttons, partial page updates—using a single, familiar API.

jQuery popularized quick UI touches like hide(), show(), fadeIn(), slideToggle(), and animate(). These were convenient for menus, notifications, and basic transitions—especially when CSS support was less reliable.

Taken together, these conveniences explain why legacy JavaScript code often starts with $( and why jQuery remained a default tool for so long.

A lot of jQuery’s reputation comes from how little code it took to do common UI tasks—especially back when browser differences were painful. A quick side-by-side makes that easier to see.

jQuery

// Select a button and run code when it's clicked

$('#save').on('click', function (e) {

e.preventDefault();

$('.status').text('Saved!');

});

Modern (vanilla) JavaScript

// Select a button and run code when it's clicked

const saveButton = document.querySelector('#save');

const status = document.querySelector('.status');

saveButton?.addEventListener('click', (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

if (status) status.textContent = 'Saved!';

});

At first glance, the jQuery version feels “cleaner”: one chain selects the element, attaches a handler, and updates text. That compactness was a major selling point.

Modern JavaScript is slightly more verbose, but it’s also more explicit:

querySelector and addEventListener tell you exactly what’s happening.textContent is a standard DOM property (no library wrapper involved).?.) and null checks make it clearer what happens if elements don’t exist.It depends on context. If you’re maintaining an older codebase that already uses jQuery everywhere, the jQuery snippet may be more consistent and quicker to work with. If you’re writing new code, modern DOM APIs are widely supported, reduce dependencies, and are easier to integrate with today’s tooling and frameworks.

For a long time, jQuery’s biggest advantage was predictability. You could write one way to select elements, attach events, or run an Ajax request—and it worked in most places.

Over the years, browsers standardized and improved. Many of the “must-have” conveniences that jQuery bundled are now built into JavaScript itself, so you often don’t need an extra library just to do the basics.

Modern DOM methods cover the most common jQuery patterns:

document.querySelector() / document.querySelectorAll() replace $(...) for many selections.element.classList.add() / .remove() / .toggle() cover class manipulation.element.addEventListener() replaced jQuery’s event wrapper for most use cases.Instead of remembering jQuery-specific helpers, you can rely on standard APIs that work across modern browsers.

Where $.ajax() used to be a go-to, fetch() now handles many everyday requests with less ceremony, especially when paired with JSON:

const res = await fetch('/api/items');

const data = await res.json();

You still need to handle errors and timeouts explicitly, but the core idea—making requests without a plugin—is now native.

jQuery introduced a lot of people to asynchronous code via callbacks and $.Deferred. Today, Promises and async/await make async flows easier to read, and ES modules make it clearer how code is organized.

That combination—modern DOM APIs + fetch + modern language features—removed much of the original reason teams reached for jQuery by default.

jQuery grew up in a “multi-page website” era: the server rendered HTML, the browser loaded a page, and you sprinkled in behavior—click handlers, animations, AJAX calls—on top of existing markup.

Modern front-end frameworks flipped that model. Instead of enhancing pages, apps often generate most of the UI in the browser and keep it in sync with data.

React, Vue, and Angular popularized the idea of building interfaces out of components—small, reusable pieces that own their markup, behavior, and state.

In this setup, the framework wants to be the source of truth for what’s on screen. It tracks state, re-renders parts of the UI when state changes, and expects you to express changes declaratively (“when X is true, show Y”).

jQuery, on the other hand, encourages imperative DOM manipulation (“find this element, change its text, hide it”). That can conflict with a framework’s rendering cycle. If you manually change DOM nodes that a component “controls,” the next re-render may overwrite your changes—or you may end up debugging inconsistencies.

As SPAs became common, teams adopted build tools and bundlers (like Webpack, Rollup, Vite). Instead of dropping a few script tags into a page, you import modules, bundle only what you use, and optimize for performance.

That shift also made people more sensitive to dependencies and bundle size. Pulling in jQuery “just in case” felt less natural when every kilobyte and third‑party update became part of the pipeline.

You can use jQuery inside a framework, but it often becomes a special-case island—harder to test, harder to reason about, and more likely to break during refactors. As a result, many teams chose framework-native patterns over jQuery-style DOM scripting.

jQuery itself isn’t “huge,” but it often arrives with baggage. Many projects that rely on jQuery also accumulate plugins (sliders, date pickers, modal libraries, validation helpers), each adding more third‑party code to download and parse. Over time, a page can end up shipping several overlapping utilities—especially when features were added quickly and never revisited.

More JavaScript generally means more for the browser to fetch, parse, and execute before the page feels responsive. That effect is easier to notice on mobile devices, slower networks, and older hardware. Even if your users eventually get a smooth experience, the “time to usable” can suffer when the page is waiting on extra scripts and their dependencies.

A common pattern in long‑lived sites is a “hybrid” codebase: some features written with jQuery, newer parts built with a framework (React, Vue, Angular), and a few vanilla JavaScript snippets sprinkled in. That mix can get confusing:

When multiple styles coexist, small changes become riskier. A developer updates a component, but an old jQuery script still reaches into the same markup and changes it, causing bugs that are hard to reproduce.

Teams gradually move away from jQuery not because it “stops working,” but because modern projects optimize for smaller bundles and clearer ownership of UI behavior. As sites grow, reducing third‑party code and standardizing on one approach usually makes performance tuning, debugging, and onboarding much easier.

jQuery didn’t just become popular—it became default. For years, it was the easiest way to make interactive pages work reliably across browsers, so it ended up embedded in countless templates, snippets, tutorials, and copy‑paste solutions.

Once that happened, jQuery became hard to avoid: even if a site only used one small feature, it often loaded the whole library because everything else assumed it was there.

A big reason jQuery still shows up is simple: its success made it “everywhere” in third‑party code. Older UI widgets, sliders, lightboxes, form validators, and theme scripts were commonly written as jQuery plugins. If a site depends on one of those components, removing jQuery can mean rewriting or replacing that dependency—not just changing a few lines.

WordPress is a huge source of “legacy jQuery.” Many themes and plugins—especially ones created years ago—use jQuery for front‑end behavior and, historically, WordPress admin screens often relied on it too. Even when newer versions move toward modern JavaScript, the long tail of existing extensions keeps jQuery present on many installations.

Older sites often prioritize “don’t break what works.” Keeping jQuery around can be the safest option when:

In short, jQuery isn’t always “forgotten”—it’s often just part of the foundation a site was built on, and foundations aren’t replaced lightly.

jQuery isn’t “bad” software—it’s just less necessary than it used to be. There are still real situations where keeping (or even adding) a little jQuery is the most practical choice, especially when you’re optimizing for time, compatibility, or stability rather than architectural purity.

If you have requirements that include older browsers (especially older versions of Internet Explorer), jQuery can still simplify DOM selection, event handling, and AJAX in ways that native APIs may not match without extra polyfills.

The key question is cost: supporting legacy browsers usually means you’ll ship extra code anyway. In that context, jQuery may be an acceptable part of the compatibility package.

If a site is already built around jQuery, small UI tweaks are often faster and safer when done in the same style as the rest of the code. Mixing approaches can create confusion (two patterns for events, two ways to manipulate the DOM), which makes maintenance harder.

A reasonable rule: if you’re touching one or two screens and the app is otherwise stable, patching with jQuery is fine—just avoid expanding jQuery usage into new “systems” you’ll later have to unwind.

For a simple marketing site or internal tool—no bundler, no transpiler, no component framework—jQuery can still be a convenient “single script tag” helper. It’s especially handy when you want a few interactions (toggle menus, simple form behaviors) and you’d rather not introduce a build pipeline.

Many mature plugins (date pickers, tables, lightboxes) were built on jQuery. If an older plugin is business-critical and stable, keeping jQuery as a dependency can be the lowest-risk option.

Before committing, check whether there’s a maintained, non-jQuery alternative—or whether upgrading the plugin will force a wider rewrite than the project can afford right now.

Moving off jQuery is less about a big rewrite and more about reducing dependency without breaking behavior people rely on. The safest approach is incremental: keep pages working while you swap pieces underneath.

Start by answering three practical questions:

This audit helps you avoid replacing things you don’t need, and it spots “hidden” dependencies like a plugin that quietly uses $.ajax().

Most teams get quick wins by swapping the simplest, most common patterns:

$(".card") → document.querySelectorAll(".card").addClass() / .removeClass() → classList.add() / classList.remove().on("click", ...) → addEventListener("click", ...)Do this in small PRs so it’s easy to review and easy to roll back.

If you use $.ajax(), migrate those calls to fetch() (or a small HTTP helper) one endpoint at a time. Keep the response shapes the same so the rest of the UI doesn’t need to change immediately.

// jQuery

$.ajax({ url: "/api/items", method: "GET" }).done(renderItems);

// Modern JS

fetch("/api/items")

.then(r => r.json())

.then(renderItems);

Before removing jQuery, add coverage where it matters: key user flows, form submissions, and any dynamic UI. Even lightweight checks (Cypress smoke tests or a QA checklist) can catch regressions early. Ship changes behind a feature flag when possible, and confirm analytics/error rates stay stable.

If you want extra safety during refactors, it helps to use tooling that supports snapshots and rollback. For example, teams modernizing legacy front ends sometimes prototype replacements in Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform for building web apps via chat) and use its snapshot/rollback workflow to iterate without losing a “known-good” version.

If you need help organizing the overall plan, see /blog/jquery-vs-vanilla-js for a comparison baseline you can use during refactors.

Migrating away from jQuery is usually less about “replacing syntax” and more about untangling years of assumptions. Here are the traps that slow teams down—and how to avoid them.

A full rewrite sounds clean, but it often creates a long-running branch, lots of regressions, and pressure to ship unfinished work. A safer approach is incremental: replace one feature or page at a time, keep behavior identical, and add tests around the pieces you touch.

If you introduce React/Vue/Svelte (or even a lightweight component system) while jQuery is still directly manipulating the same DOM nodes, you can get “UI tug-of-war”: the framework re-renders and overwrites jQuery changes, while jQuery updates elements the framework thinks it owns.

Rule of thumb: pick a clear boundary. Either:

A lot of older code relies on delegated events like:

$(document).on('click', '.btn', handler)

Native DOM can do this, but the matching and this/event.target expectations can change. Common bugs include handlers firing for the wrong element (because of nested icons/spans) or not firing for dynamically added items because the listener was attached to the wrong ancestor. When replacing delegated events, confirm:

closest() is often needed)jQuery UI effects and custom animations sometimes hid accessibility issues by accident—or introduced them. When you replace fades, slides, and toggles, re-check:

aria-expanded on disclosure buttons)prefers-reduced-motion)Catching these pitfalls early makes your migration faster and your UI more reliable—even before the last $() disappears.

jQuery isn’t “bad.” It solved real problems—especially when browsers behaved differently and building interactive pages meant writing lots of repetitive DOM code. What changed is that you usually don’t need it anymore for new projects.

A few forces pushed it from “default choice” to “legacy dependency”:

If you’re maintaining an older site, jQuery can still be a perfectly reasonable tool—especially for small fixes, stable plugins, or pages that don’t justify a full rebuild. If you’re building new features, aim for native JavaScript first and only keep jQuery where it clearly saves time.

To keep learning in a way that maps to real work, continue with:

If you’re evaluating how to modernize faster, consider tools that help you prototype and ship incrementally. Koder.ai can be useful here: you can describe the behavior you want in chat, generate a React-based UI and a Go/PostgreSQL backend when needed, and export source code once you’re ready to integrate with an existing codebase.

If you’re evaluating tooling or support options, you can also review options here: /pricing

jQuery is a JavaScript library that simplifies common browser tasks like selecting elements, handling events, making Ajax requests, and doing basic effects (show/hide, fades, slides). Its signature pattern is using the $() function to find elements and then chain actions on them.

$ is just a shortcut function (usually provided by jQuery) that finds elements in the page—similar to document.querySelectorAll()—and returns a jQuery object you can chain methods on.

If you see $() in older code, it often means “select something, then do something with it.”

It became popular because it made inconsistent browser behavior feel consistent. In the early days, simple things like events, DOM traversal, and Ajax often required browser-specific workarounds.

jQuery provided one predictable API so teams could ship faster with fewer cross-browser surprises.

Mostly because modern browsers and JavaScript caught up. Today you can often replace classic jQuery tasks with built-in features:

querySelector / querySelectorAll for selectionclassList for class changesNo. Many existing sites still use it, and it continues to work. “Legacy” usually means it’s more common in older codebases than in new ones.

The practical question is whether it’s worth keeping based on performance, maintenance, and your current dependencies (especially plugins).

Because it’s embedded in older ecosystems—especially themes and plugins. A common example is WordPress, where many extensions historically assumed jQuery was present.

If your site depends on a jQuery-only plugin (sliders, date pickers, lightboxes, validators), removing jQuery often means replacing that plugin, not just rewriting a few lines.

Yes, in a few practical situations:

In these cases, stability and speed can matter more than reducing dependencies.

Start incrementally and measure impact:

Event delegation is a common one. jQuery code like $(document).on('click', '.btn', handler) often relies on jQuery’s behavior around matching and this.

In native code you typically need:

event.target.closest('.btn') to identify the intended elementYes—effects and DOM rewrites can accidentally break accessibility. When replacing hide()/show() or slide/fade behaviors, re-check:

aria-expandedprefers-reduced-motion)Keeping behavior identical isn’t just visual; it’s interaction and keyboard flow too.

addEventListener for eventsfetch + async/await for requestsSo new projects don’t need a compatibility layer for the basics as often.

$.ajax()fetch()Small PRs and staged rollouts reduce regression risk.

Test dynamic content cases (elements added after page load).